Siege of Rouen (1418–1419)

| Siege of Rouen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Hundred Years' War | |||||||

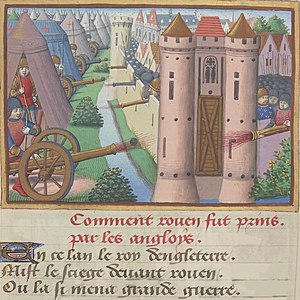

The siege depicted in a late 15th-century miniature | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Kingdom of England | Kingdom of France (Burgundian party)[1] | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

King Henry V Duke of Clarence Duke of Exeter Earl of Salisbury Earl of Huntingdon Sir John Cornwall[2] |

Guy Le Bouteiller Alain Blanchard | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000 troops[3] | 4,000 troops[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown troop casualties |

Unknown troop casualties 12,000 civilian casualties | ||||||

Location within Seine-Maritime | |||||||

The siege of Rouen (29 July 1418 – 19 January 1419)[5] was a major event in the Hundred Years' War, in which English forces loyal to Henry V captured Rouen, the capital of Normandy, from the Norman French.[6][7]

Background

At the time of the siege, the city had a population of 20,000,[6] making it one of the leading cities in France, and its capture was crucial to the Normandy campaign.[4] From about 1415, Rouen had been strengthened and reinforced by the French and was the most formidably defended place that the English had yet faced.[citation needed] The previous year, Henry V had successfully taken another important city in Normandy following the siege of Caen.

Prelude

When the English reached Rouen, the walls were defended by 60 towers, each containing three cannons, and six gates protected by barbicans.[4][7] The garrison of Rouen had been reinforced by 4,000 men and there were some 16,000 civilians willing to endure a siege.[4] The defences were lined by an army of crossbow men under the command of Alain Blanchard, commander of the crossbows (arbalétriers), and second in command to Guy le Bouteiller, a Burgundian captain and the overall commander.[4][5]

Siege

To besiege the city, Henry set up four fortified camps and barricaded the River Seine with iron chains, completely surrounding the city,[7][4] with the English intending to starve out the defenders.[6][8] The Duke of Burgundy, John the Fearless, had just captured Paris from the Armagnacs. He did not make an attempt to save Rouen and advised citizens to look after themselves.[8] By December, the inhabitants were eating cats, dogs, horses, and even mice and the streets were filled with starving citizens.[8] The city expelled more than 12,000 of the poor to save food,[8] but Henry would not allow them to pass through the siege line, and they were forced to live without sustenance in the defensive ditch in front of the city wall.[9][8] Even the English felt sorry for the starving people.[8] On Christmas Day 1418, King Henry allowed two priests to give them food, but the day soon ended, and the people went back to dying miserably in the ditch.[citation needed]

Despite several sorties by the French garrison, this state of affairs continued. On New Year's Eve, Boutellier asked for negotiations. Following ten days of negotiation, the defenders decided they would surrender on 19 January 1419 if no help had arrived,[10] on the agreed terms that the surviving French would be allowed to keep their homes and property if they gave up 80 hostages, paid 300,000 gold crowns, and swore allegiance to the English.[5][10] Alain Blanchard, who had hung English prisoners from the walls, was one of three notables decapitated by the English when the city fell.[citation needed]

Aftermath

Henry went on to take all of Normandy apart from Mont-Saint-Michel, which withstood a blockade.[7][10] Rouen became the main English base in northern France, allowing Henry to launch campaigns on Paris and to the south.[5][11]

Citations

- ^ Sumption 2015, pp. 588–589, 594.

- ^ Sumption 2015, p. 586.

- ^ Barker 2009, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f Barker 2009, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d Wagner 2006, p. 322.

- ^ a b c Brenner 2015, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Kaufmann & Kaufmann 2004, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d e f Barker 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Wagner 2006, p. 272.

- ^ a b c Barker 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Barker 2009, p. 24.

References

- Barker, Juliet (2009). Conquest: The English Kingdom of France (PDF). London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0083-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-12.

- Brenner, Elma (2015). Leprosy and Charity in Medieval Rouen. Boydell & Brewer. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-861-93339-6.

- Kaufmann, J. E.; Kaufmann, H. W. (2004). The Medieval Fortress: Castles, Forts and Walled Cities of the Middle Ages. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81358-0.

- Sumption, Jonathan (2015). The Hundred Years War IV: Cursed Kings. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-27454-3.

- Wagner, John (2006). Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32736-0.