Sicherheitsdienst

| Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers-SS (SD) | |

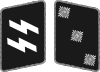

SD sleeve insignia | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | March 1931 |

| Preceding agency |

|

| Dissolved | 8 May 1945 |

| Type | Intelligence agency |

| Jurisdiction | |

| Headquarters | Prinz-Albrecht-Straße, Berlin |

| Employees | 6,482 c. February 1944[1] |

| Minister responsible |

|

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent agency | Reich Security Main Office |

Sicherheitsdienst (German: [ˈzɪçɐhaɪtsˌdiːnst] ⓘ, "Security Service"), full title Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers-SS ("Security Service of the Reichsführer-SS"), or SD, was the intelligence agency of the SS and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Established in 1931, the SD was the first Nazi intelligence organization and the Gestapo (formed in 1933) was considered its sister organization through the integration of SS members and operational procedures. The SD was administered as an independent SS office between 1933 and 1939. That year, the SD was transferred over to the Reich Security Main Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt; RSHA), as one of its seven departments.[2] Its first director, Reinhard Heydrich, intended for the SD to bring every single individual within the Third Reich's reach under "continuous supervision".[3]

Following Germany's defeat in World War II, the tribunal at the Nuremberg trials officially declared that the SD was a criminal organisation, along with the rest of Heydrich's RSHA (including the Gestapo) both individually and as branches of the SS in the collective.[4] Heydrich was assassinated in 1942; his successor, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, was convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg trials, sentenced to death and hanged in 1946.[5]

History

Origins

The SD, one of the oldest security organizations of the SS, was first formed in 1931 as the Ic-Dienst (Intelligence Service[a]) operating out of a single apartment and reporting directly to Heinrich Himmler. Himmler appointed a former junior naval officer, Reinhard Heydrich, to organise the small agency.[6] The office was renamed Sicherheitsdienst (SD) in the summer of 1932.[7] The SD became more powerful after the Nazi Party took control of Germany in 1933 and the SS started infiltrating all leading positions of the security apparatus of the Reich. Even before Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933, the SD was a veritable "watchdog" over the SS and over members of the Nazi Party and played a critical role in consolidating political-police powers into the hands of Himmler and Heydrich.[8]

Growth of SD and SS power

Once Hitler was appointed Chancellor by German President Paul von Hindenburg, he quickly made efforts to manipulate the aging president. On 28 February 1933, Hitler convinced Hindenburg to declare a state of emergency which suspended all civil liberties throughout Germany, due at least in part to the Reichstag fire on the previous night. Hitler assured Hindenburg throughout that he was attempting to stabilize the tumultuous political scene in Germany by taking a "defensive measure against Communist acts of violence endangering the state".[9] Wasting no time, Himmler set the SD in motion as they began creating an extensive card-index of the Nazi regime's political opponents, arresting labor organizers, socialists, Jewish leaders, journalists, and communists in the process, sending them to the newly established prison facility near Munich, Dachau.[10] Himmler's SS and SD made their presence felt at once by helping rid the regime of its known political enemies and its perceived ones, as well. As far as Heydrich and Himmler were concerned, the SD left their mission somewhat vaguely defined so as to "remain an instrument for all eventualities".[11] One such eventuality would soon arise.

For a while, the SS competed with the Sturmabteilung (SA) for influence within Germany. Himmler distrusted the SA and came to deplore the "rabble-rousing" brownshirts (despite once having been a member) and what he saw as indecent sexual deviants amid its leadership.[12] At least one pretext to secure additional influence for Himmler's SS and Heydrich's SD in "protecting" Hitler and securing his absolute trust in their intelligence collection abilities, involved thwarting a plot from Ernst Röhm's SA using subversive means.[13]

On 20 April 1934 Hermann Göring handed over control of the Geheime Staatspolizei (Gestapo) to Himmler. Heydrich, named chief of the Gestapo by Himmler on 22 April 1934, also continued as head of the SD.[14] These events further extended Himmler's control of the security mechanism of the Reich, which by proxy also strengthened the surveillance power of Heydrich's SD, as both entities methodically infiltrated every police agency in Germany.[15] Subsequently, the SD was made the sole "party information service" on 9 June 1934.[16]

Under pressure from the Reichswehr (German armed forces) leadership (whose members viewed the enormous armed forces of the SA as an existential threat) and with the collusion of Göring, Joseph Goebbels, the Gestapo and SD, Hitler was led to believe that Röhm's SA posed a serious conspiratorial threat requiring a drastic and immediate solution.[17] For its part, the SD provided fictitious information that there was an assassination plot on Hitler's life and that an SA putsch to assume power was imminent since the SA were allegedly amassing weapons.[18] Additionally, reports were coming into the SD and Gestapo that the vulgarity of the SA's behavior was damaging the party and was even making antisemitism less palatable.[19] On 30 June 1934 the SS and Gestapo acted in coordinated mass arrests that continued for two days. The SS took one of its most decisive steps in eliminating its competition for command of security within Germany and established itself firmly in the Nazi hierarchy, making the SS and its intelligence organ, the SD, responsible only to the Führer. The purge became known as the Night of the Long Knives, with up to 200 people killed in the action.[20] Moreover, the brutal crushing of the SA and its leadership sent a clear message to everyone that opposition to Hitler's regime could be fatal.[21] It struck fear across the Nazi leadership as to the tangible concern of the reach and influence of Himmler's intelligence collection and policing powers.[22]

SD and Austria

During the autumn of 1937, Hitler secured Mussolini's support to annex Austria (Mussolini was originally apprehensive of the Nazi takeover of Austria) and informed his generals of his intentions to invade both Austria and Czechoslovakia.[23] Getting Mussolini to approve political intrigue against Austria was a major accomplishment, as the Italian Duce had expressed great concern previously in the wake of an Austrian SS unit's attempt to stage a coup not more than three weeks after the Röhm affair, an episode that embarrassed the SS, enraged Hitler, and ended in the assassination of Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss on 25 July 1934.[24] Nonetheless, to facilitate the incorporation of Austria into the greater Reich, the SD and Gestapo went to work arresting people immediately, using lists compiled by Heydrich.[25] Heydrich's SD and Austrian SS members received financing from Berlin to harass Austrian Chancellor von Schuschnigg's government all throughout 1937. One section of the SD that was nothing more than a front for subversive activities against Austria ironically promoted "German-Austrian peace".[26]

Throughout the events leading to the Anschluß and even after the Nazis marched into Austria on 12 March 1938, Heydrich – convinced that only his SD could pull off a peaceful union between the two German-speaking nations – organized demonstrations, conducted clandestine operations, ordered terror attacks, distributed propaganda materials, encouraged the intimidation of opponents, and had his SS and SD personnel round up prominent anti-Nazis, most of whom ended up in Mauthausen concentration camp[27] The coordinated efforts of the SiPo and Heydrich's SD during the first days of the Anschluß effectively eliminated all forms of possible political, military and economic resistance within Austria.[28] Once the annexation became official, the Austrian police were immediately subordinated to Heydrich's SD, the SS and Gestapo.[29] Machinations by the SD, the Gestapo, and the SS helped to bring Austria fully into Hitler's grasp and on 13 March 1938, he signed into law the union with Austria as tears streamed down his face.[30]

"Case Green" and the Sudetenland

Concomitant to its machinations against Austria, the SD also became involved in subversive activities throughout Czechoslovakia. Focusing on the Sudetenland with its 3 million ethnic Germans and the disharmony there which the Czech government could not seem to remedy, Hitler set Heydrich's SD in motion in what came to be known as "Case Green".[31] Passed off as a mission to liberate Sudeten Germans from alleged Czech persecution, Case Green was in fact a contingency plan to outright invade and destroy the country, as Hitler intended to "wipe Czechoslovakia off the map."[32]

This operation was akin to earlier SD efforts in Austria; however, unlike Austria, the Czechs fielded their own Secret Service, against which Heydrich had to contend.[33] Once "Case Green" began, Heydrich's SD spies began covertly gathering intelligence, even going so far as having SD agents use their spouses and children in the cover scheme. The operation covered every conceivable type of intelligence data, using a myriad of cameras and photographic equipment, focusing efforts on important strategic locations like government buildings, police stations, postal services, public utilities, logistical routes, and above all, airfields.[34]

Hitler worked out a sophisticated plan to acquire the Sudetenland, including manipulating Slovak nationalists to vie for independence and the suppression of this movement by the Czech government. Under directions from Heydrich, SD operative Alfred Naujocks was re-activated to engage in sabotage activities designed to incite a response from the Slovaks and the Czechs, a mission that ultimately failed.[35] In June 1938 a directive from the SD head office indicated that Hitler issued an order at Jueterbog to his generals to prepare for the invasion of Czechoslovakia.[36] To hasten a presumed heavy response from the French, British, and Czechs, Hitler then upped the stakes and claimed that the Czechs were slaughtering Sudeten Germans. He demanded the unconditional and prompt cession of the Sudetenland to Germany in order to secure the safety of endangered ethnic Germans.[37] Around this time, early plots by select members of the German General Staff emerged, plans which included ridding themselves of Hitler.[38]

Eventually a diplomatic showdown pitting Hitler against the governments of Czechoslovakia, Great Britain, and France, whose tepid reaction to the Austrian Anschluss had precipitated this crisis to some degree, ensued. The Sudetenland Crisis came to an end when Neville Chamberlain and Hitler signed the Munich Agreement on 29 September 1938, effectively ceding the Sudetenland to Nazi Germany.[39] Involvement in international affairs by the SD certainly did not end there and the agency remained active in foreign operations to such a degree that the head of the Reich Foreign Ministry office, Joachim von Ribbentrop, complained of their meddling, since Hitler would apparently make decisions based on SD reports without consulting him.[40] According to historian Richard Breitman, there was animosity between the SS leadership and Ribbentrop's Foreign Office atop their "jurisdictional disputes".[41][b]

Intrigue against Poland

Aside from its participation in diminishing the power of the SA and its scheme to kill Röhm, the SD took part in international intrigue, first by activities in Austria, again in Czechoslovakia, and then by helping provoke the "reactive" war against Poland. Code-named "Operation Himmler" and part of Hitler's plan to justify an attack upon Poland, the SD's clandestine activity for this mission included faking a Polish attack against "innocent Germans" at a German radio station in Gleiwitz.[42] The SD took concentration-camp inmates condemned to die, and fitted them with Polish Army uniforms which Heinz Jost had acquired from Admiral Wilhelm Canaris' Abwehr (military intelligence).[43] Leading this mission and personally selected by Heydrich was SS veteran Alfred Naujocks, who later reported during a War Criminal proceeding that he brought a Polish-speaking German along so he could broadcast a message in Polish from the German radio station "under siege" to the effect that it was time for an all out confrontation between Germans and Poles. To add documented proof of this attack, the SD operatives placed the fictitious Polish troops (killed by lethal injection, then shot for appearance) around the "attacked" radio station with the intention of taking members of the press to the site of the incident.[44] Immediately in the wake of the staged incidents on 1 September 1939, Hitler proclaimed from the Reichstag in a famous radio address that German soldiers had been "returning" fire since 5:45 in the morning, setting the Second World War in Europe into motion.[45]

Tasks and general structure

The SD was tasked with the detection of actual or potential enemies of the Nazi leadership and the neutralization of such opposition, whether internal or external. To fulfill this task, the SD developed an organization of agents and informants throughout the Reich and later throughout the occupied territories, all part of the development of an extensive SS state and a totalitarian regime without parallel.[46] The organization consisted of a few hundred full-time agents and several thousand informants. Historian George C. Browder writes that SD regiments were comparable to SS regiments, in that:

SD districts (Bezirke) emerged covering several Party circuits (Kreis) or an entire district (Gau). Below this level, SD sub-districts (Unterbezirke) slowly developed. They were originally to cover a single Kreis, and, in turn, to be composed of wards (Revier), but such an ambitious network never emerged. Eventually, the SD-sub-districts acquired the simple designation of 'outposts' (Aussenstellen) as the lowest level-office in the field structure.[47]

The SD was mainly an information-gathering agency, while the Gestapo—and to a degree the Criminal Police (Kriminalpolizei or Kripo)—was the executive agency of the political-police system. The SD and Gestapo did have integration through SS members holding dual positions in each branch. Nevertheless, there was some jurisdictional overlap and operational conflict between the SD and Gestapo.[48] In addition, the Criminal Police kept a level of independence since its structure had been longer-established.[49]

As part and parcel of its intelligence operations, the SD carefully tracked foreign opinion and criticism of Nazi policies, censoring when necessary and likewise publishing hostile political cartoons in the SS weekly magazine, Das Schwarze Korps.[50] An additional task assigned to the SD and the Gestapo involved keeping tabs on the morale of the German population at large,[51] which meant they were charged to "carefully supervise the political health of the German ethnic body" and once any symptoms of "disease and germs" appeared, it was their job to "remove them by every appropriate means".[52] Regular reports—including opinion polls, press dispatches, and information bulletins were established. These were monitored and reviewed by the head of the Inland-SD, Otto Ohlendorf (responsible for intelligence and security within Germany) and by the former Heidelberg professor and SD member Reinhard Höhn. This activity aimed to control and assess the "life domain" or Lebensgebiet of the German population.[53] Gathered information was then distributed by the SD through secret internal political reports entitled Meldungen aus dem Reich (reports from the Reich) to the upper echelons of the Nazi Party, enabling Hitler's régime to evaluate the general morale and attitude of the German people so they could be manipulated by the Nazi propaganda machine in timely fashion.[54] When the Nuremberg Laws were passed in 1935, the SD reported that the measures against the Jews were well received by the German populace.[55]

In 1936, the police were divided into the Ordnungspolizei (Orpo or Order Police) and the Sicherheitspolizei (SiPo or Security Police).[56] The Orpo consisted mainly of the Schutzpolizei (urban police), the Gendarmerie (rural police) and the Gemeindepolizei (municipal police). The SiPo was composed of the Kripo and the Gestapo. Heydrich became Chief of the SiPo and continued as Chief of the SD.[57]

Continued escalation of antisemitic policies in the spring of 1937 from the SD's Department of Jewish Affairs (German: Abteilung II/112: Juden) – staffed by members like Adolf Eichmann, Herbert Hagen, and Theodor Dannecker – led to the eventual removal (Entfernung) of Jews from Germany; regardless of concerns about where they were headed.[58] Adolf Eichmann's original task (in his capacity as deputy for the Jewish Affairs department within the SD) was at first to remove any semblance of "Jewish influence from all spheres of public life", which included the encouragement of wholesale Jewish emigration. Official bureaucratization increased apace with numerous specialized offices formed, aiding towards the overall persecution of the Jews.[59]

Because the Gestapo and the SD had parallel duties, Heydrich tried to reduce any confusion or related territorial disputes through a decree on 1 July 1937, clearly defining the SD's areas of responsibility as those dealing with "learning (Wissenschaft), art, party and state, constitution and administration, foreign lands, Freemasonry and associations" whereas the "Gestapo's jurisdiction was Marxism, treason, and emigrants".[60] Additionally, the SD was responsible for matters related to "churches and sects, pacifism, the Jews, right-wing movements", as well as "the economy, and the Press", but the SD was instructed to "avoid all matters which touched the 'state police executive powers' (staatspolizeiliche Vollzugsmaßnahmen) since these belonged to the Gestapo, as did all individual cases."[61]

In 1938, the SD was made the intelligence organization for the State as well as for the Nazi Party,[62] supporting the Gestapo and working with the General and Interior Administration. As such, the SD came into immediate, fierce competition with German military intelligence, the Abwehr, which was headed by Admiral Canaris. The competition stemmed from Heydrich and Himmler's intention to absorb the Abwehr and Admiral Canaris' view of the SD as an amateur upstart. Canaris refused to give up the autonomy that his military intelligence organ possessed. Additional problems also existed, like the racial exemption for members of the Abwehr from the Nazi Aryan-screening process, and then there was competition for resources which occurred throughout Nazi Germany's existence.[63]

On 27 September 1939, the SiPo became a part of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) under Heydrich:[64]

- SD-Inland became Amt (department) III (internal intelligence – within Germany) under Otto Ohlendorf

- the Gestapo became Amt IV under Heinrich Müller

- the Kripo became Amt V under Arthur Nebe

- SD-Ausland became Amt VI (foreign intelligence – outside Germany) under Walter Schellenberg

From February 1944 forward, the sections of the Abwehr were incorporated into Amt VI.[65][2]

The SD's relationship with the Einsatzgruppen

The SD was the overarching agency under which the Einsatzgruppen der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD, also known as the Einsatzgruppen, was subordinated; this was one of the principal reasons for the later war-crimes indictment against the organization by the Allies.[c] The Einsatzgruppen's part in the Holocaust has been well documented. Its mobile killing units were active in the implementation of the Final Solution (the plan for genocide) in the territories overrun by the Nazi war machine.[66] This SD subsidiary worked closely with the Wehrmacht in persecuting Jews, communists, partisans, and other groups, as well.[d] Starting with the invasion of Poland throughout the campaign in the East, the Einsatzgruppen ruthlessly killed anyone suspected of being an opponent of the regime, either real or imagined.[e] The men of the Einsatzgruppen were recruited from the SD, Gestapo, Kripo, Orpo, and Waffen-SS.[69]

On 31 July 1941, Göring gave written authorisation to SD Chief Heydrich to ensure a government-wide cooperative effort in the implementation of the so-called Final Solution to the Jewish question in territories under German control.[70] An SD headquarter's memorandum indicated that the SD was tasked to accompany military invasions and assist in pacification efforts. The memo explicitly stated:

The SD will, where possible, follow up immediately behind the troops as they move in and, as in the Reich, will assume responsibility for the security of political life. Within the Reich, security measures are the responsibility of the Gestapo with SD cooperation. In occupied territory, measures will be under the direction of a senior SD commander; Gestapo officials will be allotted to individual Einsatzstäbe. It will be necessary to make available for special deployment a unit of Verfügungstruppe or Totenkopf [Death Head] formations.[71]

Correspondingly, SD affiliated units, including the Einsatzgruppen followed German troops into Austria, the Sudetenland, Bohemia, Moravia, Poland, Lithuania, as well as Russia.[72][f] Since their task included cooperating with military leadership and vice versa, suppression of opposition in the occupied territories was a joint venture.[73][74] There were territorial disputes and disagreement about how some of these policies were to be implemented.[75] Nonetheless, by June 1941, the SS and the SD task forces were systematically shooting Jewish men of military age, which soon turned to "gunning down" old people, women, and children in the occupied areas.[76]

On 20 January 1942, Heydrich chaired a meeting, now called the Wannsee Conference, to discuss the implementation of the plan.[77] Facilities such as Chelmno, Majdanek, Sobibor, Treblinka, and Auschwitz have their origins in the planning actions undertaken by Heydrich.[78] Heydrich remained chief of the Security Police (SiPo) and the SD (through the RSHA) until his assassination in 1942, after which Ernst Kaltenbrunner was named chief by Himmler on 30 January 1943, and remained there until the end of the war.[79] The SD was declared a criminal organization after the war and its members were tried as war criminals at Nuremberg.[g] Whatever their original purpose, the SD and SS were ultimately created to identify and eradicate internal enemies of the State, as well as to pacify, subjugate, and exploit conquered territories and peoples.[81]

Organization

The SS Security Service, known as the SS SD-Amt, became the official security organization of the Nazi Party in 1934. Consisting at first of paid agents and a few hundred unpaid informants scattered across Germany, the SD was quickly professionalized under Heydrich, who commissioned National Socialist academics and lawyers to ensure that the SS and its Security Service in particular, operated "within the framework of National Socialist ideology."[82] Heydrich was given the power to select men for the SS Security Service from among any SS subdivisions since Himmler considered the organization of the SD as important.[83] In September 1939, the SD was divided into two departments, the interior department (Inland-SD) and the foreign department (Ausland-SD), and placed under the authority of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA).[84]

Inland-SD

The Interior Security Service (Inland-SD), responsible for intelligence and security within Germany, was known earlier as Department II and later, when placed under the Reich Security Main Office, as its Department III. It was originally headed by Hermann Behrends and from September 1939 by Otto Ohlendorf.[85][h] It was within this organization that Adolf Eichmann began working out the details for the Final Solution to the Jewish Question.[87] Department III was divided into the following sections:

- Section A (Law and Legal Structures)

- Section B (Race and Ethnic Matters)

- Section C (Cultural and Religious Matters)

- Section D (Industry and Commerce)

- Section E (High Society)[88]

Ausland-SD

The Foreign Security Service (Ausland-SD), responsible for intelligence activities beyond the boundaries of Germany, was known earlier as Department III and later, after September 1939, as Department VI of the Reich Security Main Office.[89] It was nominally commanded by Heydrich, but run by his chief of staff Heinz Jost.[90] In March 1942 Jost was fired and replaced by Walter Schellenberg, a deputy of Heydrich. After the 20 July plot in 1944, Department VI took over the functions of the Military Intelligence Service (Abwehr). Department VI was divided into the following sections:

- Section A (Organization and Administration)

- Section B (Espionage in the West)

- Section C (Espionage in the Soviet Union and Japan)

- Section D (Espionage in the American sphere)

- Section E (Espionage in Eastern Europe)

- Section F (Technical Matters)[91]

Security forces

The SD and the SiPo were the main sources of officers for the security forces in occupied territories. SD-SiPo led battalions were typically placed under the command of the SS and Police Leaders, reporting directly to the RSHA in Berlin. The SD also maintained a presence at all concentration camps and supplied personnel, on an as-needed basis, to such special action troops as the Einsatzgruppen.[92] In fact, all members of the Einsatzgruppen wore the SD sleeve diamond on their uniforms.[93][i]

The SD-SiPo was the primary agency, in conjunction with the Ordnungspolizei, assigned to maintain order and security in the Nazi ghettos established by the Germans throughout occupied Eastern Europe.[95] On 7 December 1941, the same day as the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the first extermination camp was opened at Chelmno near Lodz by Ernst Damzog, the SD and SiPo commander in occupied Poznań (Posen). Damzog had personally selected the staff for the killing centre and later supervised the daily operation of the camp, which was under the command of Herbert Lange.[96] Over a span of approximately 15 months, 150,000 people were killed there.[97]

Infiltration

According to the book Piercing the Reich, the SD was infiltrated in 1944 by a former Russian national who was working for the Americans. The agent's parents had fled the Russian Revolution, and he had been raised in Berlin, and then moved to Paris. He was recruited by Albert Jolis of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Seventh Army detachment. The mission was codenamed RUPPERT.[98]

How extensive the SD's knowledge was about the early plots to kill Hitler by key members of the military remains a contested subject and a veritable unknown. According to British historian John Wheeler-Bennett, "in view of the wholesale destruction of Gestapo archives it is improbable that this knowledge will ever be forthcoming. That the authorities were aware of serious 'defeatism' is certain, but it is doubtful whether they suspected anyone of outright treason."[99]

Personnel

Given the nature of the intelligence operations assigned to the SD, there were clear delineations between what constituted a full member (Mitglied) of the SD and those who were considered "associates" (Mitarbeiter) with a further subset for clerical support personnel (typists, file clerks, etc.) who were connoted as V-persons (Vertrauensleute).[100] All SD personnel, whether simply associates or full members were required to swear an oath of secrecy, had to meet all the requirements for SS membership, were assigned SD code numbers (Chiffre Nummer) and if they were "above the level of V-person" they had to carry "an SD identification card."[101] The vast majority of early SD members were relatively young, but the officers were typically older by comparison; nevertheless, the average age of an SD member was approximately 2 years older than the average Nazi Party member.[102] Much like the Nazi revolution in general, membership in the SS and the SD appealed more to the impressionable youth.[103] Most SD members were Protestant by faith, had served in the military, and generally had a significant amount of education, representing "an educated elite" in the general sense – with about 14 percent of them earning doctorate degrees.[104] Heydrich viewed the SD as spiritual-elite leaders within the SS and the "cream of the cream of the NSDAP."[105]

According to historian George C. Browder, "SD men represented no pathological or psychically susceptible group. Few were wild or extreme Nazi fanatics. In those respects they were 'ordinary men'. Yet in most other respects, they were an extraordinary mix of men, drawn together by a unique mix of missions."[106] Along with members of the Gestapo, SD personnel were "regarded with a mixture of fear and foreboding," and people wanted as little to do with them as possible.[107] Belonging to the security apparatus of Nazi Germany obviously had its advantages but it was also fraught with occupationally related social disadvantages as well, and if post-war descriptions of the SD by historians are any indication, membership therein implied being a part of a "ubiquitous secret society" which was "sinister" and a "messenger of terror" not just for the German population, but within the "ranks of the Nazi Party itself."[108][j]

Uniforms and insignia

The SD used SS-ranks. When in uniform they wore the grey Waffen-SS uniform with army and Ordnungspolizei rank insignia on the shoulder straps, and SS rank insignia on the left collar patch. The right collar patch was black without the ![]() runes. The branch color of the SD was green. The SD sleeve diamond (SD Raute) insignia was worn on the lower left sleeve.[109]

runes. The branch color of the SD was green. The SD sleeve diamond (SD Raute) insignia was worn on the lower left sleeve.[109]

- SD men in Poland 1939. The SD men are wearing army shoulder straps, akin to the Waffen-SS,[111] except for the Rottenführer in the front seat, who is wearing the older shoulder straps of the Allgemeine SS.

- M43 field tunic, with SS rank insignia and SD diamond on lower part of sleeve

| Sicherheitspolizei [112] | Rank insignia [112] | Sicherheitsdienst [112] |

|---|---|---|

| Reichskriminaldirektor |  |

SS-Oberführer |

| Regierungs und Kriminaldirektor |  |

SS-Standartenführer |

| Oberregierungs und Kriminalrat |  |

SS-Obersturmbannführer |

| Regierungs und Kriminalrat |  |

SS-Sturmbannführer |

| Kriminaldirektor | ||

| Kriminalrat with more than three years at this grade | ||

| Kriminalkommissar |  |

SS-Hauptsturmführer |

| Kriminalinspektor | SS-Obersturmführer | |

| Kriminalobersekretär |  |

SS-Untersturmführer |

| Kriminalsekretär | SS-Hauptscharführer | |

| Kriminaloberassistent |  |

SS-Oberscharführer |

| Kriminalassistent |  |

SS-Scharführer |

See also

References

Informational notes

- ^ The "Ic" abbreviation in German military staff structures designated "military intelligence"

- ^ Following the Sudetenland Crisis, the SD then took part in operations against Poland.

- ^ For more on the creation of this organization, see: Browder, George C. Foundations of the Nazi Police State: The Formation of Sipo and SD. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2004, [1990].

- ^ At the end of March 1941, Hitler communicated his intention to 200 senior Wehrmacht officers about his decision to eradicate political criminals in the occupied regions, a task many of them were only too happy to hand-over to Himmler's Einsatzgruppen and SiPo.[67]

- ^ Victor Klemperer, one of the few Jews who survived the Nazi regime through his marriage to a German, claims that the real enemy of the Nazis was always the Jew, no matter who or what actually stood before them.[68]

- ^ From September 1939, the Einsatzgruppen came under the overall command of the RSHA. See: Nuremberg Trial, Vol. 20, Day 194.

- ^ Twenty-four Einsatzgruppen commanders (men with the SD sleeve diamond on their uniforms) were tried after the war, becoming infamous for their brutality.[80]

- ^ So severe were the interior policies of the Nazis under the watchful eye of the Department III, that when slave labor was brought into Germany to supplement the workforce during the war, German citizens who showed any kindness to foreign workers by giving them food or clothing were often punished.[86]

- ^ Many leading men in the SD had broad-ranging responsibilities across the network of interlocking Nazi agencies charged with the Reich's security; Werner Best proves a telling example in this regard, as he was not only an SD functionary, he was also an "Einsatzgruppen-organizer," the head of the military government in France, and "the Reich Plenipotentiary in Denmark."[94]

- ^ The SD also maintained local offices in Germany's cities and larger towns. The small offices were known as SD-Unterabschnitte, and the larger offices were referred to as SD-Abschnitte. All SD offices answered to a local commander known as the Inspektor des Sicherheitspolizei und SD who, in turn, was under the dual command of the RSHA and local SS and Police Leaders.

Citations

- ^ Gellately 1992, p. 44 fn.

- ^ a b Weale 2012, pp. 140–144.

- ^ Buchheim 1968, pp. 166–167.

- ^ "Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression" (1946).

- ^ Weale 2012, pp. 410–411.

- ^ Gerwarth 2011, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Longerich 2012, p. 125.

- ^ Gellately 1992, p. 65.

- ^ Shirer 1990, pp. 191–194.

- ^ Distel & Jakusch 1978, p. 46.

- ^ Browder 1996, p. 127.

- ^ Blandford 2001, pp. 47–51.

- ^ Höhne 2001, pp. 93–131.

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 61.

- ^ Blandford 2001, pp. 60–63.

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 129.

- ^ Blandford 2001, pp. 67–78.

- ^ Delarue 2008, p. 113.

- ^ Kulva 1984, pp. 582–600.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 309–313.

- ^ Kershaw 2000, pp. 521–522.

- ^ Reitlinger 1989, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Beller 2007, p. 228.

- ^ Blandford 2001, p. 81.

- ^ Dederichs 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Blandford 2001, p. 135.

- ^ Blandford 2001, pp. 134–140.

- ^ Langerbein 2003, p. 22.

- ^ Blandford 2001, p. 141.

- ^ Fest 2002, p. 548.

- ^ Blandford 2001, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Childers 2017, p. 403.

- ^ Blandford 2001, p. 144.

- ^ Blandford 2001, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Höhne 2001, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Reitlinger 1989, p. 116.

- ^ Fest 2002, pp. 554–557.

- ^ Shirer 1990, pp. 366–384.

- ^ Kershaw 2001, pp. 121–125.

- ^ Höhne 2001, p. 283.

- ^ Breitman 1991, p. 222.

- ^ Weinberg 2005, p. 748.

- ^ Williams 2003, p. 9.

- ^ Shirer 1990, pp. 518–520.

- ^ Benz 2007, p. 170.

- ^ Bracher 1970, pp. 350–362.

- ^ Browder 1996, p. 109.

- ^ Weale 2010, pp. 134, 135.

- ^ Buchheim 1968, pp. 166–187.

- ^ Koonz 2005, p. 238.

- ^ Wall 1997, pp. 183–187.

- ^ Frei 1993, p. 103.

- ^ Ingrao 2013, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Ingrao 2013, pp. 107–116.

- ^ Koonz 2005, p. 190.

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 77.

- ^ Weale 2012, pp. 134, 135.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Johnson 1999, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Gellately 1992, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Gellately 1992, p. 67.

- ^ Wall 1997, p. 77.

- ^ Blandford 2001, pp. 11–25.

- ^ Gerwarth 2011, p. 163.

- ^ Buchheim 1968, p. 172–187.

- ^ McNab 2009, pp. 113, 123–124.

- ^ Höhne 2001, pp. 354–356.

- ^ Klemperer 2000, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 185.

- ^ Browning 2004, p. 315.

- ^ Buchheim 1968, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Fritz 2011, pp. 94–98.

- ^ Wette 2007, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Müller 2012, p. 153.

- ^ Buchheim 1968, pp. 178–187.

- ^ Frei 2008, p. 155.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 696–697.

- ^ Wright 1968, p. 127.

- ^ Weale 2012, p. 149.

- ^ Rhodes 2003, p. 274.

- ^ Mayer 2012, p. 162.

- ^ Weale 2012, p. 130.

- ^ Browder 1996, p. 116.

- ^ Weale 2012, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Weale 2012, pp. 135, 141.

- ^ Stephenson 2008, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Weale 2012, p. 135.

- ^ Delarue 2008, pp. 355–356.

- ^ Doerries 2007, pp. 21, 80.

- ^ Weale 2012, p. 136.

- ^ Delarue 2008, pp. 357–358.

- ^ Reitlinger 1989, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Dams & Stolle 2014, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Gregor 2008, p. 4.

- ^ Spielvogel 2004, p. 278.

- ^ Friedlander 1995, pp. 136–140, 286–289.

- ^ Dederichs 2006, p. 115.

- ^ Persico 1979, pp. 103–107.

- ^ Wheeler-Bennett 1954, p. 475.

- ^ Browder 1996, p. 131.

- ^ Browder 1996, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Kater 1983, pp. 141, 261.

- ^ Ziegler 1989, pp. 59–79.

- ^ Browder 1996, pp. 136–138.

- ^ Dederichs 2006, p. 53.

- ^ Browder 1996, p. 174.

- ^ Gellately 1992, p. 143.

- ^ Höhne 2001, p. 210.

- ^ Mollo & 1j92, pp. 33–36.

- ^ Mollo 1992, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Mollo 1992, pp. 37–39.

- ^ a b c Mollo 1992, pp. 38–39, 54.

Bibliography

- Beller, Steven (2007). A Concise History of Austria. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52147-886-1.

- Benz, Wolfgang (2007). A Concise History of the Third Reich. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-52025-383-4.

- Blandford, Edmund L. (2001). SS Intelligence: The Nazi Secret Service. Edison, NJ: Castle Books. ISBN 978-0-78581-398-9.

- Bracher, Karl-Dietrich (1970). The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure, and Effects of National Socialism. New York: Praeger Publishers. ASIN B001JZ4T16.

- Breitman, Richard (1991). The Architect of Genocide: Himmler and the Final Solution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-39456-841-6.

- Browder, George C. (1990). Foundations of the Nazi Police State: The Formation of Sipo and SD. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-81311-697-6.

- Browder, George C (1996). Hitler's Enforcers: The Gestapo and the SS Security Service in the Nazi Revolution. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19820-297-4.

- Browning, Christopher R. (2004). The Origins of the Final Solution : The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 – March 1942. Comprehensive History of the Holocaust. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1327-1.

- Buchheim, Hans (1968). "The SS – Instrument of Domination". In Krausnik, Helmut; Buchheim, Hans; Broszat, Martin; Jacobsen, Hans-Adolf (eds.). Anatomy of the SS State. New York: Walker and Company. ISBN 978-0-00211-026-6.

- Childers, Thomas (2017). The Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-45165-113-3.

- Dams, Carsten; Stolle, Michael (2014). The Gestapo: Power and Terror in the Third Reich. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19966-921-9.

- Dederichs, Mario R. (2006). Heydrich: The Face of Evil. Newbury: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-85367-803-5.

- Delarue, Jacques (2008). The Gestapo: A History of Horror. New York: Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-60239-246-5.

- Distel, Barbara; Jakusch, Ruth (1978). Concentration Camp Dachau, 1933–1945'. Munich: Comité International de Dachau. ISBN 978-3-87490-528-2.

- Doerries, Reinhard R. (2007). Hitler's Last Chief of Foreign Intelligence: Allied interrogations of Walter Schellenberg. Portland: Frank Cass Publishers. ISBN 978-0-41544-932-8.

- Fest, Joachim (2002) [1974]. Hitler. Orlando, FL: Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-15602-754-0.

- Frei, Norbert (1993). National Socialist Rule in Germany: The Führer State, 1933–1945. Cambridge, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-63118-507-9.

- Frei, Norbert (2008). "Auschwitz and the Germans: History, Knowledge, and Memory". In Neil Gregor (ed.). Nazism, War and Genocide. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85989-806-5.

- Friedlander, Henry (1995). The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-80782-208-1.

- Fritz, Stephen G. (2011). Ostkrieg: Hitler's War of Extermination in the East. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-81313-416-1.

- Gellately, Robert (1992). The Gestapo and German Society: Enforcing Racial Policy, 1933–1945. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19820-297-4.

- Gerwarth, Robert (2011). Hitler's Hangman: The Life of Heydrich. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11575-8.

- Gregor, Neil (2008). "Nazism–A Political Religion". In Neil Gregor (ed.). Nazism, War and Genocide. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85989-806-5.

- Höhne, Heinz (2001) [1969]. The Order of the Death's Head: The Story of Hitler's SS. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14139-012-3.

- Ingrao, Christian (2013). Believe and Destroy: Intellectuals in the SS War Machine. Malden, MA: Polity. ISBN 978-0-74566-026-4.

- Johnson, Eric (1999). Nazi Terror: The Gestapo, Jews, and Ordinary Germans. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04908-0.

- Kater, Michael H. (1983). The Nazi Party: A Social Profile of Members and Leaders, 1919–1945. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67460-655-5.

- Kershaw, Ian (2000) [1999]. Hitler: 1889–1936: Hubris. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393320350.

- Kershaw, Ian (2001) [2000]. Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis. New York; London: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393322521.

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

- Klemperer, Victor (2000). Language of the Third Reich: LTI: Lingua Tertii Imperii. New York and London: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-82649-130-5.

- Koonz, Claudia (2005). The Nazi Conscience. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-067401-842-6.

- Kulva, Otto Dov (1984). "Die Nürnberger Rassengesetze und die deutsche Bevölkerung im Lichte geheimer NS-Lage und Stimmungsberichte" (PDF). Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (in German). 32 (1). Munich: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH: 582–624. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- Langerbein, Helmut (2003). Hitler's Death Squads: The Logic of Mass Murder. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-285-0.

- Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- Longerich, Peter (2012). Heinrich Himmler: A Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-959232-6.

- Mayer, Arno (2012). Why Did the Heavens Not Darken?: The "Final Solution" in History. New York: Verso Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84467-777-1.

- McNab, Chris (2009). The SS: 1923–1945. London: Amber Books. ISBN 978-1-906626-49-5.

- Mollo, Andrew (1992). Uniforms of the SS. Vol. 5. Sicherheitsdienst und Sicherheitspolizei 1931–1945. London: Windrow & Greene. ISBN 978-1-87200-462-4.

- Müller, Rolf-Dieter (2012). Hitler's Wehrmacht, 1935–1945. München: Oldenburg Wissenschaftsverlag. ISBN 978-3-48671-298-8.

- "Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression". Yale Law School—The Avalon Project. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1946. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- Persico, Joseph E. (1979). Piercing the Reich: The Penetration of Nazi Germany by American Secret Agents During World War II. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-55490-1.

- Reitlinger, Gerald (1989). The SS: Alibi of a Nation, 1922–1945. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80351-2.

- Rhodes, Richard (2003). Masters of Death: The SS-Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust. New York: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-37570-822-0.

- Shirer, William (1990) [1959]. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: MJF Books. ISBN 978-1-56731-163-1.

- Spielvogel, Jackson (2004). Hitler and Nazi Germany: A History. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13189-877-6.

- Stephenson, Jill (2008). "Germans, Slavs, and the Burden of Work in Rural Southern Germany during the Second World War". In Neil Gregor (ed.). Nazism, War and Genocide. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85989-806-5.

- Wall, Donald D. (1997). Nazi Germany and World War II. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing. ISBN 978-0-31409-360-8.

- Weale, Adrian (2012). Army of Evil: A History of the SS. New York: Caliber Printing. ISBN 978-0-451-23791-0.

- Weinberg, Gerhard (2005). Hitler's Foreign Policy 1933–1939: The Road to World War II. New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 978-1-92963-191-9.

- Wheeler-Bennett, John W. (1954). Nemesis of Power: The German Army in Politics 1918–1945. New York: St. Martin's Press. ASIN B0007DL1S0.

- Wette, Wolfram (2007). The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67402-577-6.

- Williams, Max (2001). Reinhard Heydrich: The Biography (Vol. 1). Church Stretton: Ulric. ISBN 0-9537577-5-7.

- Williams, Max (2003). Reinhard Heydrich: The Biography, Volume 2—Enigma. Church Stretton: Ulric Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9537577-6-3.

- Wright, Gordon (1968). The Ordeal of Total War, 1939–1945. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-0613140-8-0.

- Ziegler, Herbert (1989). Nazi Germany's New Aristocracy: The SS Leadership, 1925–1939. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-60636-1.

External links

Media related to Sicherheitsdienst at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sicherheitsdienst at Wikimedia Commons

![SD diamond. Here with white piping, as used by members of the Gestapo when in uniform (if members of the SS).[110]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/SDInsigna.jpg/87px-SDInsigna.jpg)

![SD men in Poland 1939. The SD men are wearing army shoulder straps, akin to the Waffen-SS,[111] except for the Rottenführer in the front seat, who is wearing the older shoulder straps of the Allgemeine SS.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/89/Bundesarchiv_Bild_101I-380-0069-37%2C_Polen%2C_Verhaftung_von_Juden%2C_SD-M%C3%A4nner.jpg/120px-Bundesarchiv_Bild_101I-380-0069-37%2C_Polen%2C_Verhaftung_von_Juden%2C_SD-M%C3%A4nner.jpg)