Siachen Glacier

| Siachen Glacier | |

|---|---|

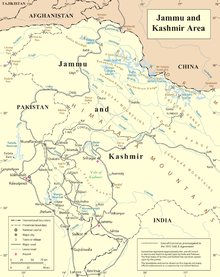

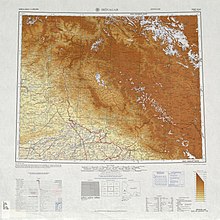

Satellite imagery of the Siachen Glacier | |

Location of the Siachen Glacier within the greater Karakoram region | |

| Type | Mountain glacier |

| Location | Karakoram, Ladakh (controlled by India, claimed by Pakistan) |

| Coordinates | 35°11′55.00″N 77°12′5.00″E / 35.1986111°N 77.2013889°E |

| Area | 2,500 km2 (970 sq mi)[1] |

| Length | 76 km (47 mi) using the longest route as is done when determining river lengths or 70 km (43 mi) if measuring from Indira Col[2] |

| |

The Siachen Glacier is a glacier located in the eastern Karakoram range in the Himalayas at about 35°25′16″N 77°06′34″E / 35.421226°N 77.109540°E, just northeast of the point NJ9842 where the Line of Control between India and Pakistan ends.[3][4] At 76 km (47 mi) long, it is the longest glacier in the Karakoram and second-longest in the world's non-polar areas.[5] It falls from an altitude of 5,753 m (18,875 ft) above sea level at its head at Indira Col on the India–China border down to 3,620 m (11,875 ft) at its terminus. The entire Siachen Glacier, with all major passes, has been under the administration of India as part of the union territory of Ladakh, located in the Kashmir region since 1984.[6][7][8][9] Pakistan maintains a territorial claim over the Siachen Glacier[10] and controls the region west of Saltoro Ridge, lying west of the glacier,[11] with Pakistani posts located 1 km below more than 100 Indian posts on the ridge.[12][13]

The Siachen Glacier lies immediately south of the great drainage divide that separates the Eurasian Plate from the Indian subcontinent in the extensively glaciated portion of the Karakoram sometimes called the "Third Pole". The glacier lies between the Saltoro Ridge immediately to the west and the main Karakoram range to the east. The Saltoro Ridge originates in the north from the Sia Kangri peak on the China border in the Karakoram range. The crest of the Saltoro Ridge's altitudes range from 5,450 to 7,720 m (17,880 to 25,330 feet). The major passes on this ridge are, from north to south, Sia La at 5,589 m (18,336 ft), Bilafond La at 5,450 m (17,880 ft), and Gyong La at 5,689 m (18,665 ft). The average winter snowfall is more than 1000 cm (35 ft) and temperatures can dip to −50 °C (−58 °F). Including all tributary glaciers, the Siachen Glacier system covers about 700 km2 (270 sq mi).

Etymology

"Sia" in the Balti language refers to the rose family plant widely dispersed in the region. "Chen" refers to any object found in abundance. Thus the name Siachen refers to a land with an abundance of roses. The naming of the glacier itself, or at least its currency, is attributed to Tom Longstaff.

Dispute

Both India and Pakistan claim sovereignty over the entire Siachen region.[3] In June 1958, first Geological Survey of India expedition went to the Siachen glacier.[14] It was the first official Indian survey of Siachen Glacier by Geological Survey of India post-1947 and that was undertaken to commemorate the International Geophysical Year in 1958. The study included snout surveying of five glaciers namely Siachen, Mamostong, Chong Kumdan, Kichik Kumdan and Aktash Glaciers in Ladakh region. 5Q 131 05 084 was the number assigned to the Siachen glacier by the expedition. U.S. and Pakistani maps in the 1970s and 1980s consistently showed a dotted line from NJ9842 (the northernmost demarcated point of the India-Pakistan cease-fire line, also known as the Line of Control) to the Karakoram Pass,[15][16][17] which India believed to be a cartographic error and in violation of the Simla Agreement. In 1984, India launched Operation Meghdoot, a military operation that gave India control over all of the Siachen Glacier, including its tributaries.[3][18] Between 1984 and 1999, frequent skirmishes took place between India and Pakistan.[19][20] Indian troops under Operation Meghdoot pre-empted Pakistan's Operation Ababeel by just one day to occupy most of the dominating heights on Saltoro Ridge to the west of Siachen Glacier.[21][22] However, more soldiers have died from the harsh weather conditions in the region than from combat.[23] Pakistan lost 353 soldiers in various operations recorded between 2003 and 2010 near Siachen, including 140 Pakistanis killed in the 2012 Gayari Sector avalanche.[24][25] Between January 2012 and July 2015, 33 Indian soldiers died due to adverse weather.[26] In December 2015, Indian Union Minister of State for Defence Rao Inderjit Singh said in a written reply in the Lok Sabha that a total of 869 Army personnel have died on the Siachen glacier due to climatic conditions and environmental and other factors from the date that the Army launched Operation Meghdoot in 1984.[27] In February 2016, Indian Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar stated that India will not vacate Siachen, as there is a trust deficit with Pakistan and also said that 915 people have died in Siachen since Operation Meghdoot in 1984.[28] According to official records, only 220 Indian soldiers have been killed by enemy bullets since 1984 in Siachen area.[29] Both India and Pakistan continue to deploy thousands of troops in the vicinity of Siachen and attempts to demilitarize the region have been so far unsuccessful. Prior to 1984, neither country had any military forces in this area.[30][31][32]

Aside from the Indian and Pakistani military presence, the glacier region is unpopulated. The nearest civilian settlement is the village of Warshi, 10 miles downstream from the Indian base camp.[33][34] The region is also extremely remote, with limited road connectivity. On the Indian side, roads go only as far as the military base camp at Dzingrulma (35°09′59″N 77°12′58″E / 35.1663°N 77.2162°E), 72 km from the head of the glacier.[35][36] The Indian Army has developed various means to reach the Siachen region, including the Manali-Leh-Khardung La-Siachen route. In 2012, Chief of Army Staff of the Indian Army General Bikram Singh said that the Indian Army should stay in the region for strategic advantages, and because a "lot of blood has been shed" by Indian armed personnel for Siachen.[37][38] The present ground positions, relatively stable for over a decade, mean that India maintains control over all of the 76 kilometres (47 mi) Siachen Glacier and all of its tributary glaciers, as well as all the main passes and heights of the Saltoro Ridge[39] immediately west of the glacier, including Sia La, Bilafond La, Gyong La, Yarma La (6,100m), and Chulung La (5,800m).[40] Pakistan controls the glacial valleys immediately west of the Saltoro Ridge.[41][42] According to TIME magazine, India gained over 1,000 square miles (3,000 km2) in territory because of its 1980s military operations in Siachen.[43] India has categorically stated that India will not pull its army from Siachen until the 110-km long AGPL is first authenticated, delineated and then demarcated.[44][45]

The 1949 Karachi agreement only carefully delineated the line of separation to point NJ9842, after which, the agreement states, the line of separation would continue "thence north to the glaciers".[4][46][47][48][49] According to the Indian stance, the line of separation should continue roughly northwards along the Saltoro Range to the west of the Siachen glacier beyond NJ9842;[50] international boundary lines that follow mountain ranges often do so by following the watershed drainage divide[44] such as that of the Saltoro Range.[51] The 1972 Simla Agreement made no change to the 1949 Line of Control in this northernmost sector.

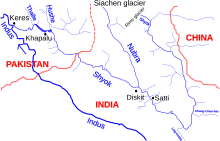

Drainage

The glacier's melting waters are the main source of the Nubra River in the Indian region of Ladakh, which drains into the Shyok River. The Shyok in turn joins the 3000 kilometre-long Indus River which flows through Pakistan. Thus, the glacier is a major source of the Indus[52] and feeds the largest irrigation system in the world.[53]

Environmental issues

The glacier was uninhabited before 1984, and the presence of thousands of troops since then has introduced pollution and melting to the glacier. To support the troops, glacial ice has been cut and melted with chemicals.[citation needed]

Dumping of non-biodegradable waste in large quantities and the use of arms and ammunition have considerably affected the ecosystem of the region.[54]

Glacial retreat

Preliminary findings of a survey by Pakistan Meteorological Department in 2007 revealed that the Siachen glacier has been retreating for the past 30 years and is melting at an alarming rate.[55] The study of satellite images of the glacier showed that the glacier is retreating at a rate of about 110 metres a year and that the glacier size has decreased by almost 35 percent.[52][56] In an eleven-year period, the glacier had receded nearly 800 metres,[57] and in seventeen years about 1700 metres. It is predicted that the glaciers of the Siachen region will be reduced to about one-fifth of their 2011 size by 2035.[58] In the twenty-nine-year period 1929–1958, well before the military occupation, the glacial retreat was recorded to be about 914 metres.[59] One of the reasons theorized for the recent glacial retreat is chemical blasting, to construct camps and posts.[60] In 2001 India laid oil pipelines (about 250 kilometres long) inside the glacier to supply kerosene and aviation fuel to the outposts from base camps.[60][61] As of 2007, the temperature rise at Siachen was estimated at 0.2-degree Celsius annually, causing melting, avalanches, and crevasses in the glacier.[62]

Waste dumping

The waste produced by the troops stationed there is dumped in the crevasses of the glacier. Mountaineers who visited the area while on climbing expeditions witnessed large amount of garbage, empty ammunition shells, parachutes etc. dumped on the glacier, that neither decomposes nor can be burned because of the extreme climatic conditions.[63] About 1,000 kilograms (1.1 short tons) of waste is produced and dumped in glacial crevasses daily by Indian forces.[55] The Indian army is said to have planned a "Green Siachen, Clean Siachen" campaign to airlift the garbage from the glacier, and to use biodigestors for biodegradable waste in the absence of oxygen and freezing temperatures.[64] Almost forty percent (40%) of the waste left at the glacier is plastic and metal, including toxins such as cobalt, cadmium and chromium that eventually affect the water of the Shyok River (which ultimately enters the Indus River near Skardu). The Indus is used for drinking and irrigation.[65][66] Research is being done by scientists of The Energy and Resources Institute, to find ways to successfully dispose of the garbage generated at the glacier using scientific means.[67] Some scientists of the Defence Research and Development Organisation who went on an expedition to Antarctica are also working to produce a bacterium that can thrive in extreme weather conditions and can be helpful in decomposing the biodegradable waste naturally.[68]

Fauna and flora

The flora and fauna of the Siachen region are also affected by the huge military presence.[65] The region is home to rare species including snow leopard, brown bear and ibex that are at risk because of the military presence.[67][69]

Border conflict

The glacier's region is the highest battleground on Earth,[70] where Pakistan and India have fought intermittently since April 1984.[71] Both countries maintain a permanent military presence in the region at a height of over 6,000 m (20,000 ft).

Both India and Pakistan have wished to disengage from the costly military outposts. India launched Operation Meghdoot to occupy Siachen Glacier in 1984. Then, due to the Pakistani incursions during the Kargil War in 1999, India abandoned plans to withdraw from Siachen, wary of further Pakistani incursions if they vacate the Siachen Glacier posts.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh became the first Indian Prime Minister to visit the area, during which he called for a peaceful resolution of the problem. After that present Prime Minister Narendra Modi also visited this place. President of Pakistan Asif Ali Zardari also visited an area near the Siachen Glacier called Gayari Sector during 2012 with Pakistan Army Chief Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani.[72] Both of them showed their commitment to resolve the Siachen conflict as early as possible. In the previous year, the President of India, Abdul Kalam became the first head of state to visit the area.

Since September 2007, India has opened up limited mountaineering and trekking expeditions to the area. The first group included cadets from Chail Military School, National Defence Academy, National Cadet Corps, Indian Military Academy, Rashtriya Indian Military College and family members of armed forces officers. The expeditions are also meant to show to the international audience that Indian troops hold "almost all dominating heights" on the key Saltoro Ridge and to show that Pakistani troops are nowhere near the Siachen Glacier.[73] Ignoring protests from Pakistan, India maintains that it does not need anyone's approval to send trekkers to Siachen, in what it says is essentially its own territory.[74] In addition, the Indian Army's Army Mountaineering Institute (AMI) functions out of the region.

Peace Park proposal

The idea of declaring the Siachen region a "Peace Park" was presented by environmentalists and peace activists in part to preserve the ecosystem of the region badly affected by the military presence.[75] In September 2003, the governments of India and Pakistan were urged by the participants of the 5th World Parks Congress held at Durban, to establish a peace park in the Siachen region to restore the natural biological system and protect species whose lives are at risk.[62] Italian ecologist Giuliano Tallone said the ecological life was at serious risk, and proposed setting up a Siachen Peace Park at the conference.[76] After a proposal of a transboundary Peace Park was floated, the International Mountaineering and Climbing Federation (UIAA) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) organised a conference at Geneva and invited Indian and Pakistani mountaineers (Mandip Singh Soin, Harish Kapadia, Nazir Sabir and Sher Khan).[77] The region was nominated for inclusion in the United Nations' World Heritage List as a part of the Karakoram range, but this was deferred by the World Heritage Committee.[78] The areas to the east and west of the Siachen region have already been declared national parks: the Karakoram Wildlife Sanctuary in India and the Central Karakoram National Park in Pakistan.[79]

Sandia National Laboratories organised conferences where military experts and environmentalists from both India and Pakistan and also from other countries were invited to present joint papers. Kent L. Biringer, a researcher at Cooperative Monitoring Center of Sandia Labs suggested setting up Siachen Science Center, a high-altitude research centre where scientists and researchers from both the countries can carry out research activities[76] related to glaciology, geology, atmospheric sciences and other related fields.[80][81]

In popular culture

The Siachen glacier was mentioned in the 2018 Hollywood movie Mission: Impossible – Fallout starring Tom Cruise and Henry Cavill. In the movie's climax, rogue agent Walker (Cavill) plants nuclear bombs at the base of Siachen glacier. The scene however was actually filmed in Preikestolen, Norway because the Indian government denied the movie makers permission to film in Kashmir.[82]

See also

- Batura Glacier

- Colonel Narendra Kumar

- NJ9842

- Indira Col

- Robert D. Hodgson

- Baltoro Glacier

- Saltoro Kangri

- Sia La

- Bilafond La

- Gyong La

- Actual Ground Position Line

- 2016 Siachen Glacier avalanche

- Siachen Muztagh

Notes

References

- ^ Desmond/Kashmir, Edward W. (31 July 1989). "The Himalayas War at the Top of the World". Time. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ^ Dinesh Kumar (13 April 2014). "30 Years of the World's Coldest War". The Tribune. Chandigarh, India. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Lyon, Peter (2008). Conflict Between India and Pakistan: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2009. ISBN 9781576077122.

- ^ a b "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India – Opinions". The Tribune.

- ^ Siachen Glacier is 76 km (47 mi) long; Tajikistan's Fedchenko Glacier is 77 km (48 mi) long. The second longest in the Karakoram Mountains is the Biafo Glacier at 63 km (39 mi). Measurements are from recent imagery, supplemented with Russian 1:200,000 scale topographic mapping as well as the 1990 "Orographic Sketch Map: Karakoram: Sheet 2", Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research, Zurich.

- ^ Gauhar, Feryal Ali; Yusuf, Ahmed (2 November 2014). "Siachen: The place of wild roses". Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ North, Andrew (12 April 2014). "Siachen dispute: India and Pakistan's glacial fight". BBC. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ "India gained control over Siachen in 1984". The Times of India. 9 April 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ "Blog: The Siachen Story, Then And Now". NDTV.com.

- ^ Siddiqui, Naveed (4 August 2020). "In landmark move, PM Imran unveils 'new political map' of Pakistan". Dawn. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Gokhale, Nitin A (2015). Beyond NJ 9842: The SIACHEN Saga. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 364. ISBN 9789384052263.

- ^ Service, Tribune News. "Life & death in world's highest combat zone". Tribuneindia News Service.

- ^ "Siachen deaths harden resolve to hold glacier: Army chief". Hindustan Times. 18 February 2016.

- ^ Paul, Amit K. (13 July 2023). "The first GSI survey of the Siachen". The Hindu.

- ^ "Kumar's line vs Hodgson's line: The 'Lakshman rekha' that started an India-Pakistan fight". 31 December 2021.

- ^ "How India got Hodgson's Line erased and won the race to Siachen". 15 October 2022.

- ^ "The 'cartographic nightmare' of the Kashmir region, explained". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021.

- ^ Wirsing, Robert (1998). War Or Peace on the Line of Control?: The India-Pakistan Dispute Over Kashmir Turns Fifty. IBRU, 1998. ISBN 9781897643310.

- ^ Dettman, Paul (2001). India Changes Course: Golden Jubilee to Millennium. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001. ISBN 9780275973087.

- ^ "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India - Opinions". The Tribune.

- ^ "Siachen height provides military depth India can't afford to lose | India News". The Times of India. 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Story of Saltoro – From Ababeel to Meghdoot". mid-day. 26 April 2012.

- ^ Rodriguez, Alex (8 April 2012). "Avalanche buries Pakistan base; 117 soldiers feared dead". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Pubby, Manu (18 September 2015). "Bleeding in Siachen: Pakistan losing 30 soldiers a year on highest battlefield". The Economic Times.

- ^ "Rescue operations at Gayari Sector after Pakistan avalanche, Photo Gallery". NDTV.com.

- ^ "33 Indian soldiers killed in Siachen since 2012: govt". Business Standard. Press Trust of India. 31 July 2015.

- ^ Dinakar Peri (11 December 2015). "In Siachen, 869 Army men died battling the elements". The Hindu.

- ^ "Won't vacate Siachen, we can't trust Pakistan, says Manohar Parrikar | India News". The Times of India. 26 February 2016.

- ^ "Here's how ISRO's space technology can save lives of soldiers at Siachen". 3 April 2016.

- ^ "Kashmir's Siachen glacier a frigid outpost in India-Pakistan conflict". CBC Canada. 7 April 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Eur (2002). Far East and Australasia 2003. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 9781857431339.

- ^ "- News18". Archived from the original on 17 January 2014.

- ^ "World's highest, biggest junkyard". The Tribune. 29 August 1998. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ "The fight for Siachen". The Express Tribune. 22 April 2012.

- ^ "Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2012.

- ^ Noorani, A. G. (26 March 2016). "Settle Siachen". Dawn. Pakistan.

- ^ "India must continue to hold on to Siachen: Bikram Singh, Army Chief General". timesofindia-economictimes. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ Mohamed Nazeer (24 November 2012). "Army should stay put in Siachen, says General Bikram Singh". The Hindu.

- ^ Shukla, Ajai (28 August 2012). "846 Indian soldiers have died in Siachen since 1984". Business Standard.

- ^ "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India – Opinions". The Tribune.

- ^ Wirsing, Robert (13 December 1991). Pakistan's security under Zia, 1977–1988: the policy imperatives of a peripheral Asian state. Palgrave Macmillan, 1991. ISBN 9780312060671.

- ^ Child, Greg (1998). Thin air: encounters in the Himalayas. The Mountaineers Books, 1998. ISBN 9780898865882.

- ^ "The Himalayas War at the Top of the World". Time. 31 July 1989. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007.

- ^ a b W. P. S. Sidhu (13 June 2013). "Siachen: While the battle continues to rage, no settlement is in sight". India Today.

- ^ Praveen Dass. "Bullish on Siachen". The Crest Edition. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ Raj Chengappa (31 October 1987). "Siachen glacier: Indian troops repulse major Pakistani offensive". India Today.

- ^ P. ANIMA (7 February 2014). "Riding on". The Hindu.

- ^ "Army opposes Pakistan's demand for troop withdrawal from Siachen Glacier – Indian Express". The Indian Express.

- ^ "UN Map showing CFL as per Karachi Agreement – UN document number S/1430/Add.2" (PDF). Dag Digital Library. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ "Why India cannot afford to give up Siachen". Rediff. 13 April 2012.

- ^ "Siachen Glacier Dispute – GKToday".

- ^ a b H.C. Sadangi (31 March 2007). India's Relations with Her Neighbours. Isha Books. p. 219. ISBN 978-8182054387. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ Rashid Faruqee (November 1999). Strategic Reforms for Agricultural Growth in Pakistan. World Bank Publications. p. 87. ISBN 978-0821343364. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ ActionAid (2010). Natural Resource Management in South Asia. Pearson Education. p. 58. ISBN 978-8131729434. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ a b K.R. Gupta (2008). Global Warming (Encyclopaedia of Environment). Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. pp. 105–112. ISBN 978-8126908813. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Y. S. Rao (3 November 2011). "Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry for Glacier Movement Studies". In Vijay P. Singh (ed.). Encyclopedia of Snow, Ice and Glaciers. Springer. pp. 1138–1142. ISBN 978-9048126415. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Harish Kapadia (March 1998). Meeting the Mountains (1st ed.). Indus Publishing Company. p. 275. ISBN 978-8173870859. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Daniel Moran (22 March 2011). Climate Change and National Security: A Country-Level Analysis. Georgetown University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-1589017412. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ K.S. Gulia (2 September 2007). Discovering Himalaya : Tourism of Himalaya Region. Isha Books. p. 92. ISBN 978-8182054103. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Snow white coffins of Siachen". The News Today. 22 April 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Asad Hakeem, Gurmeet Kanwal; Michael Vannoni; Gaurav Rajen (September 2007). "Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring" (PDF). Albuquerque, New Mexico: Sandia National Laboratories. p. 28. SAND2007-5670. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ a b Isa Daudpota; Arshad H. Abbasi (16 February 2007). "Exchange Siachen confrontation for peace". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 20 February 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ Harish Kapadia (30 November 1999). Across Peaks & Passes in Ladakh, Zanskar & East Karakoram. Indus Publishing Company. pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-8173871009. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ "Military activity leads to melting of Siachen glaciers". Dawn. 24 March 2007. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ a b Neal A. Kemkar (2006). "Environmental peacemaking: Ending conflict between India and Pakistan on the Siachen Glacier through the creation of a transboundary peace park" (PDF). Stanford Environmental Law Journal. 25 (1). Stanford, California: Stanford University School of Law: 67–121. ANA-074909. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Kevin Fedarko (1 February 2003). Jackson, Nicholas (ed.). "The Coldest War". Outside. Mariah Media Network. ASIN B001OTEIG8. ISSN 0278-1433. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ a b Supriya Bezbaruah (1 November 2004). "Siachen Snow Under Fire". India Today. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ Mahendra Gaur (8 August 2006). Indian Affairs Annual 2006. Kalpaz Publications. p. 84. ISBN 978-8178355290. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ^ Emmanuel Duparcq (11 April 2012). "Siachen tragedy – day 5: Bad weather dogs avalanche search efforts". The Express Tribune. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ^ Kamal Thakur (1 November 2014). "16 Things You Should Know About India's Soldiers Defending Siachen". Topyaps. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "How a tiny line on a map led to conflict in the Himalaya". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021.

- ^ "Pakistan wants resolution of Siachen issue: Kayani". The Express Tribune. 18 April 2012.

- ^ India opens Siachen to trekkers The Times of India 13 September 2007

- ^ India hits back at Pak over Siachen issue The Times of India 17 September 2007

- ^ Teresita C. Schaffer (20 December 2005). Kashmir: The Economics of Peace Building. Center for Strategic & International Studies. p. 57. ISBN 978-0892064809. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ a b Sujan Dutta (14 June 2005). "Out of the box ideas for glacier: Siachen could become bio reserve or peace park". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ^ Harish Kapadia (1 December 2005). "Chapter 34: Siachen: A Peace Proposal". In Yogendra Bali, R. S. Somi (ed.). Incredible Himalayas. Indus Books. pp. 213–217. ISBN 978-8173871795. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Jim Thorsell; Larry Hamilton (September 2002). "Sites deferred by the Committee which may merit re-nomination" (PDF). A Global Overview of Mountain Protected Areas on the World Heritage List. International Union for Conservation of Nature. p. 15. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ G. Tamburelli (1 January 2007). Biodiversity conservation and protected areas. Giuffrè. p. 6. ISBN 978-8814133657. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ K. L. Biringer (1 March 1998). Siachen Science Center: A concept for cooperation at the top of the world (Cooperative Monitoring Center Occasional Paper No. SAND—98-0505/2, 589204). Sandia National Laboratories. doi:10.2172/589204. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ Wajahat Ali (20 August 2004). "US expert at Sandia wants Siachen converted into Science Centre". Daily Times. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ^ "Tom Cruise's mission impossible..." Hindustan Times. 27 July 2018.

Further reading

- Myra MacDonald (2008) Heights of Madness: One Woman's Journey in Pursuit of a Secret War, Rupa, New Delhi ISBN 8129112922. The first full account of the Siachen war to be told from the Indian and Pakistani sides.

- V. R. Raghavan, Siachen: Conflict Without End, Viking, New Delhi, 2002

- TIME Asia's cover story on Siachen Glacier (July 11, 2005)

- Kunal Verma / Rajiv Williams, The Long Road to Siachen: the Question Why, Rupa & Co., New Delhi, 2010

- Analysis: Peace may return to Siachen – The Washington Times

- Siachen by Arshad H Abbasi

External links

- Video about the Conflict in the Siachen area and its consequences

- Siachen Peace Park Initiative

- Outside magazine article about Siachen battleground

- BBC News report: Nuclear rivals in Siachen talks; 26 May 2005

- Confrontation at Siachen, Bharat Rakshak. Archived 7 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- National Geographic article: Siachen Glacier Tragedy