Railroad classes

Railroad classes are the system by which freight railroads are designated in the United States. Railroads are assigned to Class I, II or III according to annual revenue criteria originally set by the Surface Transportation Board in 1992. With annual adjustments for inflation, the 2019 thresholds were US$504,803,294 for Class I carriers and US$40,384,263 for Class II carriers. (Smaller carriers were Class III by default.)

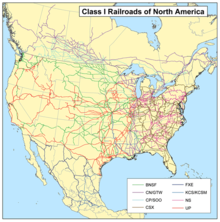

There are six Class I freight railroad companies in the United States: BNSF Railway, CSX Transportation, Canadian National Railway, CPKC, Norfolk Southern Railway, and Union Pacific Railroad. Canadian National also operates in Canada and CPKC operates in Canada and Mexico.

In addition, the national passenger railroad in the United States, Amtrak, would qualify as Class I if it were a freight carrier, as would Canada's Via Rail passenger service. Mexico's Ferromex freight railroad would also qualify as Class I, but it does not operate within the United States.

Background

Initially (in 1911) the former federal agency Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) classified railroads by their annual gross revenue. Class I railroads had an annual operating revenue of at least $1 million, while Class III railroad incomes were under $100,000. Railroads in both classes were subject to reporting requirements on a quarterly or annual schedule. In 1925, the ICC reported 174 Class I railroads, 282 Class II railroads, and 348 Class III railroads.[1]

The $1 million criterion established in 1911 for a Class I railroad was used until January 1, 1956, when the figure was increased to $3 million. In 1956, the ICC counted 113 Class I line-haul operating railroads (excluding "3 class I companies in systems") and 309 Class II railroads (excluding "3 class II companies in systems"). The Class III category was dropped in 1956 but reinstated in 1978. By 1963, the number of Class I railroads had dropped to 102; cutoffs were increased to $5 million by 1965,[2] to $10 million in 1976 and to $50 million in 1978, at which point only 41 railroads qualified as Class I.

In a special move in 1979, all switching and terminal railroads were re-designated Class III — even those with Class I or Class II revenues.

In early 1991, two Class II railroads, Montana Rail Link and Wisconsin Central, asked the ICC to increase the minimum annual operating revenue criteria (then established at US$93.5 million) to avoid being redesignated as Class I, which would have resulted in increased administrative and legal costs.[3] The Class II maximum criterion was increased in 1992 to $250 million annually, which resulted in the Florida East Coast Railway having its status changed to Class II.

The thresholds set in 1992 were:

- Class I: A carrier earning revenue greater than $250 million

- Class II: A carrier earning revenue between $20 million and $250 million

- Class III: A carrier earning revenue less than $20 million

Since dissolution of the ICC in 1996, the Surface Transportation Board (STB) has become responsible for defining criteria for each railroad class. The STB continues to use designations of Class II and Class III as there are different labor regulations for the two classes. The bounds are typically redefined every several years to adjust for inflation and other factors.

Class II and Class III designations are now rarely used outside the rail transport industry. The Association of American Railroads typically divides non–Class I companies into three categories:

- Regional railroads: operate at least 350 miles (560 km) or have revenue of at least $40 million per year.

- Local railroads: smaller than a regional railroad, but engage in line-haul service.

- Switching and terminal railroads: mainly switch cars between other railroads and/or provide service in a common terminal.

Classes

In the United States, the Surface Transportation Board categorizes rail carriers into Class I, Class II, and Class III based on the carrier's annual revenue. The thresholds, last adjusted for inflation in 2019, are:[4]

- Class I: A carrier earning revenue greater than $504,803,294

- Class II: A carrier earning revenue between $40,387,772 and $504,803,294

- Class III: A carrier earning revenue less than $40,387,772

In Canada, a Class I rail carrier is defined (as of 2004) as a company that has earned gross revenues exceeding $250 million (CAD) for each of the previous two years.[5]

Class I

Class I railroads are the largest rail carriers in the United States. In 1900, there were 132 Class I railroads, but as the result of mergers and bankruptcies, the industry has consolidated and as of April 2023, just six Class I freight railroads remain.

BNSF Railway and Union Pacific Railroad have a duopoly over all transcontinental freight rail lines in the Western United States, while CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern Railway operate most of the trackage in the Eastern United States, with the Mississippi River being the rough dividing line. Canadian National Railway (via its subsidiary Grand Trunk Corporation) operates north–south lines near the Mississippi River. Canadian Pacific Kansas City, doing business as CPKC, runs from southern Canada, then goes south through the central United States to central Mexico.

In addition, the national passenger railroads in the US and Canada—Amtrak and Via Rail—would both qualify as Class I if they were freight carriers. Mexico's Ferromex would qualify as a Class I railroad if it had trackage in the United States.

| Railroad | Trackage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | United States | Mexico | |

| BNSF Railway | Yes | Yes | No |

| Canadian National Railway | Yes | Yes [Note 1] |

No |

| CPKC | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CSX Transportation | Yes | Yes | No |

| Norfolk Southern Railway | Yes | Yes | No |

| Union Pacific Railroad | No | Yes | No |

- ^ Operated by Grand Trunk Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Canadian National Railway.

Class II

A Class II railroad in the United States hauls freight and is mid-sized in terms of operating revenue. Switching and terminal railroads are excluded from Class II status. Railroads considered by the Association of American Railroads as "Regional Railroads" are typically Class II. Some examples of Class II railroads would be the Florida East Coast Railway, the Iowa Interstate Railroad, and the Alabama and Gulf Coast Railway.

Class III

Class III railroads are typically local shortline railroads serving a small number of towns and industries or hauling cars for one or more railroads; often, they once had been branch lines of larger railroads or even abandoned portions of main lines. Some Class III railroads are owned by railroad holding companies such as Genesee & Wyoming or Watco. Some examples of Class III railroads would be the Maryland and Delaware Railroad, the San Pedro Valley Railroad, and the Buckingham Branch Railroad.

See also

- List of U.S. Class I railroads

- List of U.S. Class II railroads

- Rail transport in Canada

- Rail transport in Mexico

- Rail transport in the United States

- Timeline of Class I railroads: 1910–1929, 1930–1976, 1977–present

References

- ^ Gathman, Bruce (December 1, 2015). "Railroad Classification" (PDF). Carolina Conductor. Carolina Railroad Heritage Association, Inc. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ New ICC classification becomes effective Railway Age February 8, 1965 page 7

- ^ Arrivals and Departures, Trains March 1991

- ^ "Surface Transportation Board Economic Data". Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ Branch, Legislative Services (June 3, 2019). "Consolidated federal laws of canada, Transportation Information Regulations".

Sources

- Surface Transportation Board FAQs – Economic and Industry Information Archived December 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- STB Ex Parte No. 647 Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Stover, John F. (1999). The Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92140-6.

External links

- List and Family Trees of North American Railroads

- Uniform Classification of Accounts and Related Railway Records (UCA); retrieved April 24, 2005.

- Surface Transportation Board FAQs – Economic and Industry Information Archived December 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine