Shire of Sherwood

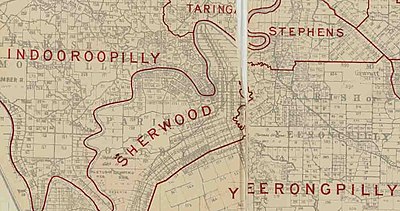

The Shire of Sherwood is a former local government area of Queensland, Australia, located in south-western Brisbane in and around the suburb of Sherwood.

History

On 11 November 1879, the Yeerongpilly Division was created as one of 74 divisions within Queensland under the Divisional Boards Act 1879. On 16 October 1886, parts of Yeerongpilly Division were excised to create Stephens Division (later Shire of Stephens).[1] On 24 January 1891, further parts of Yeerongpilly Division were excised to create Sherwood Division (later Shire of Sherwood).

With the passage of the Local Authorities Act 1902, Sherwood became a Shire on 31 March 1903.[2]

On 1 October 1925, the Shire of Sherwood was amalgamated into the City of Brisbane.[3]

Chairmen and presidents

Other notable members include:

- Robert Dickson Alison Frew, noted for his development of the Milton Tennis Centre

The Sherwood Shire was located on the fringe of Brisbane. In 1891 Sherwood was proclaimed a local government area, being part of the Yeerongpilly Division established by Xlll the Divisional Board Act of 1879, which instituted local government to sparsely populated districts of Queensland. The future Sherwood Shire contained an area of 22 square miles. The most northerly landmark, Oxley Point (Chelmer), was on the Brisbane River, 5 miles southwest of Brisbane. Reaching this point by the Brisbane River, involved a journey of twelve miles. The northern and western boundaries of the shire were the Brisbane River from the mouth of Oxley Creek to Woogaroo Creek in the south-west with Oxley Creek forming the eastern boundary. The southern boundary was the upper reaches of the Oxley creek proceeding in a south-easterly direction to a point 1 mile above the mouth of Woogaroo Creek to its junction with the Brisbane River.[7]

Early history

Brisbane River

Three shipwrecked and disoriented ticket of leave convicts, Pamphlet, Finnegan and Parsons in June 1823 were walking and were diverted by the river to the mouth of Oxley Creek. The discovery of two native canoes allowed them to cross the river and journey downstream. John Oxley in December 1823 named the creek 'Canoe Creek' in recognition of the discovery, but in time it was renamed Oxley Creek.[7]

During the 1820s, the river was used by convicts to convey limestone from Limestone Hill (Ipswich) to the penal settlement at Brisbane. From 1842, the river was the regular means of transport between Brisbane and Ipswich. The Seventeen Mile Rocks caused delays to laden vessels until the tide rose sufficiently to pass. From the 1860s, local selectors transported produce by river to Ipswich and Brisbane with tide times influencing the lifestyle of the early farmers. The steamer, 'The Fairy', provided a daily service between Brisbane and Oxley Point (Chelmer) until 1875, when it sank when colliding with another vessel.[8][7]

In 1863, a flash flood caused inconvenience to new selectors, with several, suffering the loss of belongings and equipment. Alexander Boyd, a farmer on Oxley Creek between 1864 and 1870, documented the common occurrence of high floods.The 1893 flood peaked 48 feet above the low tide mark at the Oxley Creek mouth, while upstream, the water rose 20 to 30 feet. The flooded Brisbane River destroyed houses, outbuildings along with farm animals destroying the railway bridge at Oxley Point. As a result of the flood, there was created a beach at Oxley Point, known as 'The Sands' becoming a popular swimming area.[9][7]

Land features

Several hills, part of a system of low ridges extending from Spring Mountain sixteen miles to the south-west, ranged from 100 to 200 feet. Two of these hills in the now residential suburbs of Corinda and Oxley, lay close to a bend of the river downstream from Seventeen Mile Rocks. From these hills, several seasonal steams coursed towards Oxley Creek forming swamps and lagoons. The largest of these swamps was situated south of Oxley Point in present-day Chelmer. In the 1940s it was designated a municipal rubbish dump and the swamp was filled in. It lay where the current sporting grounds are now situated on the eastern side of the Chelmer Station. The hills and ridges on the southern boundary fed other streams such as Bullock Head Creek and Sandy Creek which combined to form Wolston Creek.[7]

Explorers and early selectors in the area recorded descriptions of the original flora. Oxley's made account of rich brush along the river, and the settlers of the 1860s referred to the dense scrub which clothed the river and creek banks and giant fig trees grew abundantly. The land's natural features influenced the lifestyle of the local Aborigines being from Jagarra tribe. This tribe's habitat lay along the Brisbane River, westwards almost to the Great Dividing Range. They referred to the land on either side of Oxley Creek as Bennawarra. The wildlife of swamps and attracted a section of the tribe known as Yerongapan.[7]

Occasionally, white contact with Aborigines led to clashes. In 1828, at Seventeen Mile Rocks, Aborigines attacked a boat from Limestone Hill, (Ipswich), killing a soldier and a convict. In 1832, there was a massacre of a convict fishing party on the Brisbane River. By the 1860s, hostilities had ceased in the local area with white settlers being permitted to witness a corroboree near Oxley Creek. Early selectors found evidence of Aboriginal sites, believing a circular floating island in the large Oxley Point (Chelmer) swamp was a bora ring. There were other reported areas used as borra rings one being between the Anglican Cemetery and Oxley Creek, and on the site of the Corinda railway station. Seventeen Mile Rocks at low tide provided crossing to Fig Tree Pocket for aboriginals, known to local Aborigines as Biami Yumba, 'the abode of the good spirits'.[7]

Early exploration and settlement

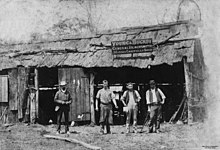

The white man first exploited the local area during the convict era, extracting pine and other building materials. Between 1825 and 1829, convicts quarried a portion of Corinda Hill for sandstone, which was used in the construction of the Commissariat and Windmill in the penal colony. This quarry was located at the western point of Quarry Street. In 1851, Thomas Boyland[10] leased land of what became the Shire, where he grazed cattle and sheep. The land became to then be known as Boyland's Pocket. After Queensland became a colony in 1859, Boyland declined and offer to purchase the land.[7]

In May 1860, the land was subdivided into 25 portions. Each portion averaged 60 acres and initially sold for £1 an acre, the area being eventually known as Oxley West. Between 1861 and 1864, 96 portions of land, were offered for sale in the area known as Oxley. In 1851, Lands Commissioner, Dr. Stephen Simpson leased 5,500 acres of land in the south-western section and purchased 640 acres where he erected his home Wolston House, near Wolston Creek. After using the property as a horse stud, he returned to England in 1860 after the death of his nephew, James Ommaney, killed when thrown from a horse while riding on the Wolston property. A hill close to where the fatality occurred was named Mt. Ommaney. Grazier, Matthew Goggs senior, purchased Simpsons holding, and enlarged it.[7]

Following the subdivision of Oxley West, the subsequent land sale attracted both speculators and immigrant settlers. There were three categories of land purchasers during the 1860s: the speculators the immigrant; and immigrants arriving after most of the land had been sold. Speculators included Governor Bowen's secretary, John Bramston, who purchased land at Oxley Point and Charles Blakeney, Frank McDougall and Arnold Wienholt, who served in either the upper or lower houses of the colonial legislature during the 1860s, but did not reside locally.[7]

Several immigrants paid their fare to Australia from Britain and on arrival received land orders which equaled the cost of their fares. However, the initial price of land, £1 per acre rose to £3, then to £6, thereby reducing the purchasing power of land orders.[11] Original land purchasers such as Alexander Boyd, William Gray and Arthur Francis settled on or near elevated land now known as Corinda Hill. Despite their farming intentions, Boyd, Gray and Francis lacked experience. Having persevered, their contribution lay outside the local area: Boyd, a school inspector; Gray, a Congregational minister; and Francis, a magistrate. Other original land purchasers being the Strong and Orr families, (Oxley West), and the Lucock and Brodie families, (Oxley), continued to earn their living in the local area as farmers. They instead chose the fertile river and creek flats.[7]

The third category of land purchaser acquired their land from either speculators or selectors. The Berry and Sinnamon families who financed their trip from Northern Ireland, initially worked for original settlers, William Gray and William Dart. Unmarried migrants, John Donaldson assisted government surveyor John Payne and John A. Dunlop labouring for William Gray.[12] They gained an intimate knowledge of the area, and along with the Berry and Sinnamon families and other latecomers like the Nosworthy and Trotter families they farmed the fertile land adjoining the Brisbane River and Oxley Creek.[7]

Farming

A number of selectors intended to grow cotton, as the American civil war disrupted shipments to British cotton manufacturers, but cash crops being bananas, vegetables and citrus fruits provided a reliable income. This idea of growing cotton was probably instilled in prospective immigrants by a Mr. Henry Jordan. He was appointed by the Queensland Government as an immigration agent in England and influenced many in the British Isles to immigrate to Queensland. He resided in Sherwood and in 1890 he died being, buried at the Sherwood Cemetery.[13] By 1870, there was an enthusiasm for growing sugar cane, as the Berry, Jimmieson, Francis and Sinnamon families established plantations along the river flats.[14] Arthur Francis employed male and female Kanakas with Christianity forming the basis of friendly relations between himself and his plantation workers. Initially Berry and Francis constructed primitive horse driven sugar mills; with Berry's mill employing up to sixty men. Thomas Berry Junior also operated a steam driven mill.[7]

During 1872, the Oxley Creek district produced 270 tons of sugar from 244 acres of harvested cane. Only half the acreage under cane was harvested, because of the effect of severe winters and accompanying frosts. By 1874 however, a disease referred to as rust, caused problems having devastated cane crops in Southern Queensland and consequently cane farming in the Oxley Creek district waned. Local farmers, like Joseph Tainton depended on reliable cereal crops and by the 1890s, farmers had added dairying to their activities, continuing into the early 1900s. The number of farmers was 58 by 1900.[7]

There were summer heatwaves of the 1860s which contrasted with the severe winters of the 1870s which had adversely affected cane farming. New settlers experienced the humid conditions typical of a semi-tropical climate. Thomas Berry senior noted the hot summer of 1863, when the temperature in Fahrenheit averaged 95 degrees in the shade and 135 degrees outside. There was a drought in 1877 and pressure was put on the State Government to build a water reservoir in the Sherwood area. In 1878 a reservoir was built to dam watercourses at the rear of the Oxley West (Sherwood) State School.[15] The most severe drought occurred between 1899 and 1902 when many of the Sinnamon family's stock perished.[7]

The characteristics of generosity, stubbornness and self-determination were attributed to William Gray, who settled locally in 1861. This was matched by the reliability and trustworthiness of John Dunlop, an early farmer and bush carpenter. William Dart, a typical agriculturalist rose at 4 am and conscientiously worked until dark, clearing and developing his holding. Arthur M. Francis, a selector of 1863 and an acquaintance of Governor, Samuel Blackall represented the large East Moreton Electorate in the Queensland Legislative Assembly between 1867 and 1870. Francis, refused to align with either liberal or conservative political parties.[7]

The wives of pioneers of the 1860s persevered living with their husbands initially living in tents and then later in slab huts, raising children, and assisting in the field. The tragic and depressing aspect of pioneering life involved the loss of children at birth or in the months following. This was put down to the lack of pre-natal care and the scarcity of milk which contributed to problems after the birth of a child. The loss of children in infancy had a prolonged effect on Angela Francis. She was motivated to establish a mid-wife training scheme for women in isolated areas. On another occasion, to prevent the possibility of naive female migrants succumbing to the adverse influences of urban life, Angela Francis trained several young females as governesses.[7]

In 1863 the residents presented a petition to government signed by 30 residents, called for the construction of a bridge over Oxley Creek which had the effect of halving the distance to the Brisbane markets. The creek had recently been bridged upstream at Oxley during the construction of a new road from Ipswich to Brisbane. The government responded by building another bridge from Sherwood over Oxley Creek in 1864, one mile from its mouth and in 1865, a road linked this bridge to Rocky Waterholes (Rocklea). In the mid-1870s, the installation of a vehicular ferry between Oxley Point (Chelmer) and Indooroopilly provided another avenue of land transport to Brisbane.[7]

Churches

Moral dilemma

In 1889, there was another petition concerning the hotel at Oxley. Rather than being a benefit to the local area, the hotel had operated as a change station for horses and a refreshment stop for coaches on Ipswich Road. In 1873, a new hotel was constructed at the intersection of present-day Ipswich and Oxley Roads. In 1889, 23 residents, in their petition expressed their objection that the new Oxley hotel, in addition to its Liquor licence, also had a Music Hall licence. There were fears that a music hall would attract the larrikin element.[7]

In the absence of a local police station until 1876, a moral influence was required due to the temptation of hotels at Oxley and Rocky Waterholes (Rocklea). Before churches were erected, males of families conducted services in their homes. In 1864, a Baptist church was built but soon closed due to lack of support. In 1863 in a tent close to present day Corinda railway station, William Gray conducted Presbyterian services.[16] Later on these services were in a hut on his nearby holding. In 1865 the first Presbyterian congregation at Oxley Creek, formed part of the pastoral charge of the Reverend Alexander Caldwell.[7]

The passing of the Liquor Act of 1912 prohibited Sunday trading, and prohibition orders were to be issued against alcoholics. Several Protestant churches continued to campaign for the prohibition of liquor to all the public. Influenced by the three Sherwood Protestant church's congregations, public opinion within the Shire ensured that hotel ownership remained confined to Oxley, with the result that suburbs from Corinda to Chelmer were free from any establishment which sold alcohol.[7]

Church formation

By the 1890s, due to the presence of three active church congregations, the suburb of Sherwood had become the religious focus of most Protestants living in the Shire. These included Presbyterian, established in 1865, St Matthews Church of England in 1868 and Wesleyan in 1886.[17] By the early 1900s there were resident clergy serving all three. During the 1890s, Catholics were a minority in the local area. Catholic population did not increase appreciably in the Sherwood Shire until the small St. Joseph's church at Corinda was erected in 1912. This church, was a part of the Goodna parish, and Annerley parish before the formation of the Corinda parish in 1923 and the appointment of Father Pat Murphy as the first parish priest.[7]

St. Matthews Church of England and the Sherwood Presbyterian Church benefited from long serving clergy.[18][19] Church of England adherents outnumbered other denominations in the area due to the appointment of a resident minister, James Hassall in 1876.[20] This was almost 10 years before the arrival of John Stewart Pollock in 1885, as the first resident minister of the Sherwood Presbyterian church.[21] Hassall, who in 1899, retired in his mid-seventies, the younger Pollock continued his ministry into the early 1900s actively supporting social issues important to his congregation.[7]

Members of the various religious denominations were invited to attend each other's social activities. These activities were the annual Sunday school picnic, to which adults and even children wore formal clothing. However, the tea meeting proved the most popular activity.[22] Selector, Alexander Boyd, considered the Oxley Creek district the great nursery of tea meetings. These meetings, held regularly in aid of building funds originated in the early 1860s as part of the planning for the erection of the Primitive Methodist Church near Rocky Waterholes (Rocklea). Because of the popularity of tea meetings it attracted visitors from the surrounding districts, many staying overnight with friends.[7]

Anglican supporters included Alan Spowers,[23] Alexander Raff,[24] and Thomas Murray Hall. Presbyterian laity comprised Theodore Dewar,[25] Robert Nosworthy, Islay Bennett and Charles Lyon. Office bearers of the Methodist church included Thomas G. Johnston,[26] John Moffatt,[26] and Joseph Tainton.[27] Sherwood primary school head teachers were also prominent: Hugh Welch as a Presbyterian elder; Eskiel Larter, choir master at St. Matthews; and Thomas Fielding,[28] a long term lay supporter of both the local Methodist Church.[7]

Presbyterian

The Presbyterians erected their first church on land donated by selector, John McDiarmid and was replaced by a weatherboard church in 1867.[16] The Reverend John Pollock was appointed in 1885 as minister of the newly formed Sherwood charge which led to the erection in 1889 of a brick and stone building which still stands on Oxley Road, Sherwood.[21] Elder, Joseph Carson, who financially assisted in the construction of the new church building by providing a £300 loan, converted this loan to an outright donation.[29][7]

The Reverend J.S. Pollock, while disposed towards conservative ideals of other Protestant clergy, exhibited a progressive attitude with regard to the involvement of the church in industrial disputes. His views eventually led to his resignation from the Presbyterian Church. By 1893, reaction to Pollock's attitude led to dissension, with some of the congregation abstaining from church attendance. Inquiries conducted by the Brisbane Presbytery into these disagreements, showed the Sherwood elders supported Pollock.[7]

Following persistent support by Pollock for aged pensions, the Presbyterian General Assembly adopted his resolution in 1906 that recognized the duty of all Christian communities to care for the poor. The Old Age Pensions Act passed by the Queensland parliament in 1908, embodied much of the spirit of Pollock's resolution.[30] In 1897, in addition to Sunday school, other activities at the Sherwood Presbyterian Church included the Band of Hope and Christian Endeavour.[31] By 1910, the 100 strong temperance society of the combined Sherwood/Kenmore charge, comprised adults as well as young people.[7]

Anglican

Local residents in 1864 held working bees to erect a non-denominational slab church at Oxley West, with the Sunday school supervised by Arthur Francis. In 1869, one year after the formation of a Church of England congregation in the Oxley West, the Governor of Queensland, Samuel Blackall, laid the foundation stone of the Church of St. Matthew at present day Sherwood. At a cost £370 to construct, it was officially opened on 6 June 1870 by the Right Reverend E.W. Tufnell, Anglican Bishop of Brisbane.[7]

The church was Gothic in design, and comfortably accommodated 130 worshippers. Land adjacent to the church served as a cemetery. In 1874, Bishop Tufnell consecrated the church and lay members, Arthur Francis and Thomas Berry senior, and on occasions the Reverend J.E. Moffatt, conducted services until all debts accrued to the erection of the church had been cleared. By 1891, a weatherboard construction had replaced this building. The Reverend James Hassall, a grandson of Samuel Marsden, was the first resident minister, serving from 1876 to 1899.[32] Hassall's sound financial circumstances saved the church the expense of a parsonage. He built and lived in two homes, Lynne-Grove House from 1880 to 1883, and then moved to Matavi until 1904.[7]

George Green, following his appointment to St Matthews Anglican Church in 1920, insisted on regular church attendance. In 1921, fire destroyed St Matthew's church.[33] Parishioners as well as Sherwood Shire residents contributed financially to the construction of a new church, enabling the foundation stone to be laid within three years. The first donation came from the local Catholic Church. This church now stands on the corner of Oxley and Sherwood Roads.[7][34]

Methodist

The founders of the first Wesleyan Church in Sherwood supported the local Presbyterian Church during the several years this church functioned without a resident minister. In 1886, one year after John Pollock was appointed as the first Presbyterian minister, the foundation meeting of the Sherwood Wesleyan Church was held in the home of Presbyterian, Thomas George Johnston.[35] By 1887, he had constructed a small timber church costing £120. In 1889, several Presbyterians who had opposed extensions to their Church building, boosted the numbers of the newly formed Wesleyan congregation.[7][35]

In 1880 at Seventeen Mile Rocks, another Methodist sect, the Bible Christians, constructed a bark and shingle building, their preachers traveling by river from Ipswich. In 1888, Church of England supporters erected a church nearby. The congregation could not attract a minister and as a result, the Primitive Methodists, consisting mostly of the original Bible Christian congregation, assumed control of the structure. This church, on Seventeen Mile Rocks Road, east of its original location, is still supported by the Sinnamon family.[7]

The new Wesleyan church, initially attached to the South Brisbane circuit, functioned without a resident minister until the appointment of Isaac Castlehow in 1903. The church, then part of the West End circuit, was renamed the Sherwood Methodist Church, following the union of Wesleyan and Primitive Methodist Churches in Queensland in 1905. In 1913, the Sherwood circuit was constituted, with William Brown as resident minister.[7]

Although the Sherwood Methodist Church building had been enlarged, there was planning in 1903 for a more substantial structure. In 1913, the congregation decided to build and by 1914, local builder and Methodist, Walter Taylor, had erected a cement and brick structure costing £1109. The congregation comprised 87 adult members. The former Primitive Methodist Church Seventeen Mile Rocks was now part of the Sherwood circuit and included a congregation at Darra. By 1920, the adult membership in the Sherwood circuit had reached 131.[7]

Catholic

During the 1860s, Father Frank Dunne, a future Archbishop of Brisbane, travelled the district attending to the spiritual needs of Catholics a minority in the district. They were able to use the first slab building erected by the Presbyterian congregation as a place of worship. Later, Catholics met in other buildings in the area until the erection of their own church, St. Josephs in the suburb of Corinda, in 1912.[7][36]

Schools

In the mid-1860s, the first private school functioned for a brief period in the Baptist church. Arthur Francis, who had difficulty surviving on a farming income, conducted an advanced school for squatter's sons, the pupils boarding with the Francis family.[37] Another less successful farmer, William Gray, a neighbour of Francis, held classes for older children and adults. These first attempts at providing private education in the local area, foreshadowed the private school at Oxley. In 1878, Janet O'Connor established Duporth, a girl's boarding school catering mostly for pupils from outside the district.[7]

In 1867, the first Government school, at Oxley West (Sherwood), had an enrollment of 117 pupils. The change of name occurred in 1878, to Sherwood. In 1869, Oxley East, (Oxley), started as a provisional school, with classes being held in the non-denominational church. In 1870, a school building was erected nearby, with an enrollment of 74 pupils. Oxley East was a non-vested or private school until 1875, when it became a Government school. In 1870, a provisional school opened at Seventeen Mile Rocks with an enrolment of 39 pupils.[7]

Being a provisional school, the Government paid the teacher's salary as well as providing some books and teaching aids, with local parents providing the building. The enthusiasm for education was not shared by all local farmers. Despite the origins of the teaching staff at Oxley West (Sherwood) school, many parents appeared apathetic towards their children's education. Alexander Boyd, a local selector in his mid-twenties, was the first head teacher at the Oxley West and Oliver Radcliffe its first pupil teacher.[38][39] By 1870, 137 out of the 193 school age children living in the district of Oxley West had enrolled, but only 50% of those attended the school regularly. This was the norm throughout the Colony of Queensland. Such an attitude had not originated locally, but was the general attitude of British migrants, unreceptive to the need for a primary school education.[7]

The first settlers on the hill in Corinda: Alexander Boyd, William Gray, and Arthur Francis and his wife Angela, were influential, due to their association with the religious and educational activities which helped stabilise the local area. Their backgrounds contributed to this with Boyd receiving his education in Europe, while Gray attended medical school prior to studying for the ministry. During the 1860s, Francis served in the Legislative Assembly of Queensland. Angela Francis emanated from the middle class and even while living in a tent she had a servant.[7]

By 1890, Sherwood and Oxley state schools catered for the children of families resident within the Sherwood Shire and in 1916, Darra State School opened. State primary school enrollments within the shire increased from 294 in 1891 to 877 in 1920. St. Joseph's convent, administered by an order of nuns, the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, had opened at Corinda in 1917 with 47 enrolments and by the early 1920s annual enrollments averaged 60.

In an effort to boost school attendance in 1900, the government enforced the compulsory clauses of the Education Act of 1875 which required children from 6 to 12 years to attend at least 60 days out of the 110 days of the school's half-year. To ensure that this was adhered to, police acted as attendance officers. There were amendments to the Education Act which raised school leaving age to 14 if a child had not reached Class 5. Primary schools in Queensland were subjected to a government curriculum containing character forming elements. During the early 1900s, the School Paper, religious instruction and lessons in civics and morals were included in the curriculum. Between 1892 and 1920, Queensland primary schools used the Royal Reader. The Queensland Government eventually introduced the Queensland Reader to coincide with another change in the syllabus in 1915.[7][40]

In 1910, the State Education Amendment Act introduced religious instruction to State schools, which increased to two hours a week, to improve the morals of school children. This followed lengthy campaign throughout Queensland by the Bible in State Schools League. With escalating criminal and immoral activities in the community it motivated this reversal by Protestant religions, who in 1875 had previously supported a secular education in government schools.[7]

Prior to the teacher training institution in 1914, Queensland State school teachers usually received training at the local primary school where they attended as pupils. Aspiring teachers trained for 3 or 4 years, and were regularly assessed as to their teaching ability. An average of three pupil teachers received training at Sherwood during the 1890s, with Oxley training one pupil teacher. Several teachers at Sherwood also served for lengthy periods with Ezekial Larter 8 years as head teacher from 1905, while his successor, Thomas Fielding, held this position for 14 years.[28] In 1910, Frances Kingsford served 27 years, Constance Sparrow, served at Sherwood from 1914 to 1953 and in 1919, John Woodyard, had 37 years' service with Sherwood. Because of their lengthy service, teachers at Sherwood taught more than one generation in a family.[7]

Railway

Railway passengers suffered inconvenience, when the railway from Ipswich to Oxley Point (Chelmer) was completed in 1875. They initially disembarked from the train at Oxley West (Sherwood) and rode the Cobb and Co coach to Brisbane. After a ferry was employed at Oxley Point (Chelmer) they were ferried across the Brisbane River to Indooroopilly to join the train to Brisbane. The change of name 1878 from Oxley West to Sherwood was made at the request of Mr. W. H. Wilson (Postmaster-General in the Queensland Parliament), Sherwood being the name of his home at Toowong, and where his ancestors had come.[41][42]

From 1874, the railway department established railway stations at Oxley, and at Oxley West (Sherwood), with a stopping place now at Darra. The Albert railway bridge connected the two lines across the river in 1876. In 1881, a new railway station was established at Chelmer with Oxley Point station made redundant, and another at Graceville in 1884.[7] Graceville station and suburb was named after Grace Grimes, the daughter of Samuel Grimes.

In 1884, a branch line was constructed of the southern and western railway, from South Brisbane Junction, half a mile south of Sherwood railway station and in 1888, this junction point was named Corinda. The line ran to the wharves on the Brisbane River at South Brisbane using Wooloongabba rail yard as a marshalling yard. Wool from the Darling Downs and coal from the West Moreton fields were transported along this line. Along this line there were trains which provided passenger accommodation three times daily.[7]

The origins of the word 'Corinda' and the naming of the railway station and suburb can be derived from a land development in 1888, called 'Corinda Township Estate' on lots 99 and 100 of the Parish of Oxley. This estate was owned and developed by Queensland politician Edward Palmer M.L.A. who owned a pastoral station 'Canobie'.[43][44] There was a pastoral station named 'Corinda' but it was owned by James Tolson near Aramac Queensland.[44][45] As these gentlemen sat on the board of the Queensland Meat Export and Agency Company there was a close association between the two. Palmer was instrumental[46] in having the railway station 'South Brisbane Junction' name changed to 'Corinda' to benefit the sales of his development.

Approximately 170 passengers traveled daily by train to Brisbane from railway stations between Darra and Chelmer during the period 1 July 1889 to 30 June 1890. During 1892, the shire residents enjoyed a daily service of 18 trains to Brisbane. After the destruction of the railway bridge at Oxley Point (Chelmer) by the 1893 flood,[47] the ferry again was commissioned to transport passengers until another railway bridge was completed in 1895. Improvements in communication for the Shire involved establishment of post offices at Oxley in 1875; Oxley West (Sherwood) in 1877; and Corinda in 1889. Railway station masters usually acted as postmasters and from 1884 and telegraphic offices operated at the local railway stations. This being because telegraph facilities were required to regulate trains along the railway line.[7]

Railway facilities in the shire caused some individuals to construct homes and reside in the shire. Because of its growing popularity as a residential area there were moves to create residential subdivisions between Chelmer and Darra. By 1891, when the Shire of Sherwood was proclaimed, the population numbered 2331, there being at least 30% of male residents listed in postal directories who followed urban rather than farming occupations.[7]

Urbanisation

In 1901, there were 311 dwellings in the Sherwood Shire. Of those, 286 were timber built and by 1919, when dwellings numbered 1100, there was still a high ration of timber homes, with most high set, complemented by verandas. Typical of the style, 'Edgecliffe', the residence of Alexander Cummings Raff of Corinda which contained four inner rooms, plus nursery, kitchen and servants quarters, and featured three rooms opening on to verandas located on three sides of the house. It was situated on almost four acres of land on the hill at Corinda.[7][48][49]

With population growth, the shire suburbs gradually expanded, with the population showing a slight increase from 2331 in 1891, to 2667 by 1900 and by 1910, it had grown to 4050. By 1919, the population had only risen to 5000. Between 1891 and 1910, building proceeded slowly but from 1910 to 1919, although population growth had eased, the number of occupied dwellings had doubled. Fluctuation in the shire's population during the 1890s and early 1900s was associated with events affecting the Brisbane area. There was a depression in 1893 which curtailed overseas immigration and affected the livelihood of those Brisbane together with the effects of the 1893 flood.[7][50]

The shire owed the increase of 1300 residents between 1901 and 1910 to a reaction to the bubonic plague in Brisbane for the period 1900–1902.[51] Subsequently, between 1920 and 1925, there was a population increase to 7000 due to recently wed couples having children. Rail transport allowed the less affluent to move to Brisbane's fringes, but high rail fares had the effect of on the number of workers migrating to the shire.[7]

By 1905, a second class single fare from Corinda to Brisbane's Central railway station cost sixpence, with first class single fares, nine pence. This compared with the small expense by workers living in the inner city who walked to work. While the rail fares may have deterred government labourers earning 8/- a day, government senior and junior clerks also found them costly. Senior clerks wages averaged £4 per week, with junior clerks £2/6/- weekly. Second class rail fares over a five and a half-day working week, accounted for at high proportion of weekly pay. The Sherwood Shire Council protested against the rail fares being higher comparative journeys. Train passengers from Chelmer to Oxley who were not holders of season tickets, increased from 64,709 in 1891, to 119,784 by 1906. By 1910, the protests by the Shire Council produced a positive response where single second class fares being reduced to twopence, with first class fares, four pence.[7]

Land subdivision

In Oxley, a village emerged close by at the intersection of Ipswich Road and the road to Oxley West (Sherwood).[52] In 1876, there was a hotel, a church, a store and a blacksmith, with only a few of the 35 to 80 perch residential allotments occupied. In 1874, with the establishment of the Oxley railway station, precipitated the subdivision of 180 residential allotments in an attempt to establish another Oxley township.[53] Further north in Oxley West, the original Sherwood Township, briefly named Rowland after the government official who surveyed it in the late 1870s, bordered the northern side of the road to Rocky Waterholes (Rocklea). Although the local school and a church were located in the surveyed area, very little residential development occurred.[7]

From the middle of the 1880s, residential subdivision adjacent to the railway began with allotments in the Sherwood Park estate located north of the railway station being offered for sale.[54][55] Subdivision south of Sherwood station produced 'Sherwood Rise Estate'.[56] In June 1888 an auction of 150 allotments in the 'Township of Sherwood' estate, situated to the east of the suburb took place.[57] It bordered the surveyed Sherwood Township. The branch railway to South Brisbane ran through the eastern section of the estate.[7]

In Graceville and Chelmer, land close to the Ipswich-Brisbane railway was sold as part of the 'Oatlands' and the 'Riverton' estates.[58][59] Other residential land for sale during this period were the 'Primrose' estate at Chelmer, the 'Johnston' estate at Sherwood, the 'Francis' estate at Corinda and the 'Gates' estate at Darra. Three of these estates were named after their former owners, Gilbert E. Primrose, Thomas George Johnston,[26] and Arthur Francis.[7]

In the 'Township of Sherwood' estate, first auctioned in June 1888, Isles Love offered 16 perch allotments at low prices and easy terms,. A water main adjacent to the area had yet to supply reticulated water to the whole estate and although the advertisement stated it was situated on a splendid high position, the 1893 flood covered half the estate. In 1910 land on Corinda Hill, six half acre allotments were offered for £80 each by estate agents King and King.[7]

The Sherwood Shire attracted several entrepreneurs, managers and professionals. Robert Disher Neilson, merchant and auctioneer of Elizabeth Street, Brisbane, established his residence on the bank of the Brisbane River adjacent to the Ipswich-Brisbane railway.[60] By 1904, in addition to his business interests he was an acting magistrate. Due to Neilson's influence, the government established a railway siding close to his home for his own use.[7]

James F. Bennett, manager of the Union Bank settled at Chelmer, and while on the hill at Corinda, Alan Spencer, an inspector with the Queensland National Bank, resided at 'The Towers'.[61] John K. Cannan, Assistant Manager of the Royal Bank, and Sydney Larard, secretary to the Brisbane Chamber of Commerce, who both moved to Chelmer during the early 1890s, still resided in the local area in the early 1900s.[62] Commercial and industrial entrepreneurs with residences at Chelmer, included Gilbert E. Primrose who founded the Helidon Spa Water Company, and Joseph W. Sutton, 'Hurlton' whose shipbuilding establishment on the Brisbane River near the city centre, was one of the few heavy industries of the 1890s.[7][63]

At Graceville during the early 1890s, newspaper proprietor and former cabinet minister, Charles H. Buzzacott, resided at the two storeyed 'Verney House' with its view of the Brisbane River.[64] From 1895 to 1901, A.H. Chambers, manager of the Union Bank occupied this home, changing its name to 'Rakeevan House'.[65] The name was subsequently changed to 'Beth-Eden'. Both Sutton and Buzzacott had imported electrical generators to provide lighting in their homes. It could be claimed these private dwellings were the first to be lit up by electricity in Australia. In the early 1890s, William Morecambe, who owned a city stationery business, settled at Oxley. Members of the legal profession, including Charles Stumm and Chief Justice, Sir Pope A. Cooper, also resided in the shire.[66] Cooper having purchased 'Ruan' the former home of Dr Henry Alexander Francis in 1914. This home later, under the ownership of Dr David Gifford Croll, became the Sherwood Private Hospital.[7] Dr Croll served in the military during WW1 and WW2 and was a founding member of the Sherwood sub-branch of the Returned and Services League, Australia (RSL). On his death in 1948, he bequeathed this building to the RSL where it remained the sub-branch meeting place until 1967.

Thomas M. Hall, lived at Lynne-Grove House, Corinda, from 1888 until the early 1920.[67] His interests focused on insurance and accountancy. In 1888, he established the Hall Mercantile Agency in Sydney and Melbourne, and located the head office in Brisbane. Later, he founded the Institute of Accountancy, and in 1906 was appointed to the Legislative Council. Several affluent residents retired in the shire, John Watts, former cabinet minister and member of the Legislative Assembly for Darling Downs, resided briefly at 'Ardoyne House', Corinda, in 1906.[68][69] Henry W. Coxen, a former Darling Downs grazier settled at 'The Fort' on Oxley heights in 1880.[70] William M. D. Davidson settled in 1876 and by 1890, he had risen to surveyor-general one of his residences being the prestigious 'Cliveden House'.[71] Frank Pratten, lived at 'Eddiston', Oxley, being Deputy-Registrar General.[7]

The land purchased by Rev. William Grey, and called Consort Cliff in Corinda was bought by Mr. Charles Collins, manager of the Union Bank in Brisbane in the 1880s, where he built a house and named it 'Ardoyne'. The house went through a number of owners until it was purchased by Queensland branch of the Red Cross Society. The Society converted it into a soldier convalescent home and the Ardoyne Hospil was opened on Armistice Day 1920.[72] Businessman and philanthropist, Mr George Marchant, bought Ardoyne and gifted the site at Consort Street, Corinda to the Queensland Society for taCrippled Children in 1937 and it was renamed the Montrose Home for Crippled Children.[73]

The middle class influence on lower classes emerged in another form within the suburban area of the Sherwood Shire, This concerned the naming of one's home. During the 1890s and early 1900s, with streets unmarked, middle class residents recorded in post office directories and electoral rolls, had the names of their homes as part of their address. English origins were evident in 'Hurlton', 'Penzance', 'King's Lynn', and 'Grosvenor'; Scottish influences in 'Doonholm', 'Heatherbank' and 'Dunalister'; with Irish ancestry obvious in 'Connemara' and 'Erin Villa'.[7]

The railway had constituted an unofficial boundary between the affluent and less affluent areas of the suburbs of Chelmer, Graceville, Sherwood, Corinda and Oxley. The area to the west of the railway, was the domain of the shire's middle class, and on the eastern side of the railway, twice as many people resided than on the western side. Between 1891 and 1920, as the suburban areas expanded, the majority of the first generation of suburban residents within the Sherwood Shire depended upon Brisbane city for employment.[7]

Industry

Enterprises at Oxley included a bacon factory established in the mid-1890s, which carried the name of Foggitt Jones by the early 1900s.[74] This company amalgamated with J.C. Hutton Pty Ltd in 1927. Another industry, Brittain's Brickworks was established in 1899.[75] By 1912, the Lahey family had constructed a sawmill at Corinda.[76] From 1916, the suburb of Darra expanded as the result of the Queensland Cement and Lime Company being established there. Under Foggitt Jones, the bacon factory located near Oxley Creek, engineered the use of waterways as a means of transport. The dredging of Oxley Creek by the government allowed small craft to transport goods downstream to Brisbane, until there was a levy on the traffic using the creek.[7]

Prior to the World War 1, Foggitt Jones employed approximately 70 workers. In 1899, William Brittain transferred the company brickworks from Booval in Ipswich, taking advantage of the clay ground to the south-west of Oxley railway station. The brickworks expanded to include pipe manufacture providing local employment for almost eighty years. The State mental hospital at Woogaroo provided residential accommodation for its employees. This government institution established in the mid-1860s, remained isolated from most of the shire.[7]

Shire council and School of Arts

Two social activities in which residents participated, involved membership of the shire council and the school of arts. From the period 1891 to 1920, almost 60 residents served as elected members of the Sherwood Shire Council. Being volunteers, they influenced and improved the lifestyle of the population, which had grown from 2331 in 1891 to 5000 by 1920.The administration of the Sherwood Shire, had its origins in the Queensland Governments experimental Local Government Act of 1878 and the Divisional Board Act of 1879. The Divisional Board Act of 1879 established Yeerongpilly Division, with the future Sherwood Shire designated number two subdivision. The Divisional Board Act of 1887, officially allowed boards to govern by committee, while the Health Act of 1884 vested local governments with responsibility for health.[7]

In 1891, following the presentation of two petitions by the ratepayers of Yeerongpilly's number two subdivision, the Queensland Government formed a new division, which it named Sherwood. In 1896, divisional boards were elevated to shire councils, ratified by section five of the Local Authorities Act of 1902. By 1905, the Brisbane metropolitan area comprised two cities, Brisbane and South Brisbane; five towns, Sandgate, Toowong, Ithaca, Windsor and Hamilton; and thirteen shires including Sherwood.[7]

Sherwood's by-laws and amendments had to receive government approval. The auditor-general scrutinized the shires finances, and the councils financial statements were regularly published in the Queensland Government Gazette. To facilitate operations, Sherwood was divided into three areas, as divisions. Number one division comprised the southern portion of Oxley, all of Darra, as well as the farming districts of Seventeen Mile Rocks and Wolston. Number two division included Corinda, the northern and eastern portions of Oxley, and the southern part of Sherwood. Number three division consisted of the northern end of Sherwood, and all of Graceville and Chelmer. Numbers two and three divisions contained most of the suburbanized portion of the shire. On Oxley Road at Corinda there was the Shire's administration building.[7]

Each division was represented by three elected members or councillors, who usually served three years and were ratepayers. One member retired annually but was eligible for re-election. The representatives of the three divisions formed the nine member shire council and elected the chairman from amongst their number. In 1920, the Local Authorities Acts Amendment Act instituted triennial elections. This required the whole council to retire, with the chairman, and the three councillors in each of the three divisions, elected by the adult residents residing in the shire rather than by the ratepayers. Women were not permitted to nominate until 1921.[7]

The chairman, John Moffatt, with William Lyon, William Orr and Alexander Brodie, depended on the land for a living.[77] Other elected members included surveyor, Thomas O'Connor; distillery operator, Samuel Knight; newspaper proprietor, Charles Buzzacott; and commission agents, Rhodes Whitaker and William Berry. Others like Matthew Goggs Junior had 20 years' service, Thomas M. Hall, 14 years, Arthur Baynes and Thomas O'Connor each 10 years. Between 1891 and 1920, Sherwood's three improvement or works committees, focused on the construction and maintenance of roads, bridges and drains.[7]

In 1924 there had been discussions about the establishment of an Arboretum in Brisbane[78] The Sherwood Shire Council had purchased the property 'Dunella' on the Brisbane River banks at Sherwood from the Ranken family for park purposes. In 1925, the Greater Brisbane Scheme saw the amalgamation of local councils and shires to establish the City of Brisbane and a proposal to dedicate land for arboretum purposes was strongly supported by the outgoing Sherwood Shire Council.

The Sherwood Forest Park was officially opened on World Forestry Day, 21 March 1925, with a planting of 72 Queensland kauri (Agathis robusta) along a central promenade named Sir Matthew Nathan Avenue in honour of the Queensland Governor. The park is known today as The Sherwood Arboretum.

Social Activities

During the early 1920s, the first Sherwood Shire agricultural, horticultural and industrial show was staged at the Rakeevan Estate of Mrs J.P. Bell. During 1895, Jack Dunlop, a member of a local pioneering family, erected the first School of Arts in the Sherwood Shire at Corinda. As there were few meeting places, he foresaw a need for such a building, and the first stage of construction, a library and auditorium, cost him £313/7/6.[7]

The School of Arts building remained under the ownership of the Dunlop family with trustees administering it, and when the shire council then assumed control, renamed the building the Shire Hall.[79] With falling membership after 1915, along with the reduced support for the library, the shire council took control of the School of Arts by 1917. After World War 1, the School of Arts served as the venue for a travelling picture show which introduced silent motion pictures to the shire. This motivated the establishment of open air cinemas in Sherwood: David Ogilvie in 1918, and Barney Cook in 1921.[7][80]

Until the erection of St. Joseph's church in 1912, the Catholic community held their services in the auditorium. In this venue the men's auxiliary of the Red Cross constructed splints and crutches for the World War 1. There was a memorial plaque on which was inscribed the names of those from the shire who enlisted in this World War 1 which is now in the Sherwood Services Club in Corinda. In 1919 during a flu epidemic, the building was used as a base from which volunteers administered to those affected households. As well as its use as a polling booth, the auditorium catered for meetings convened by local candidates standing for election elections.[7]

The School of Arts featured prominently among the few public and commercial buildings which had emerged in Corinda by the early 1900s. In 1888, the railway station provided Corinda with its name, as well as serving as a post office. In 1903, the re-located Oxley police station was set up in Corinda, opposite Dow's bakery. Only one police officer was stationed locally from 1876 to 1911. From 1911, a second police officer was stationed on Ipswich Road near the Oxley Hotel, supervising districts beyond the shire boundary.[7]

Lodges

The first lodge founded in 1876 in the Shire area was the Oxley True Blues Orange Lodge. In 1896, the Freemasons formed the Hopeful Masonic Lodge. Between 1900 and 1920, four friendly societies established themselves being the Pride of Oxley Oddfellows Lodge, Loyal Sherwood Forest Oddfellows Lodge, Alliance Rechabites Tent and the Sherwood Oak Druids Lodge.[81] The origins and functions of these institutions varied.[7]

Orders such as the Oddfellows, Rechabites, Foresters and Druids, functioned as fraternal organizations meeting weekly or fortnightly. Three members of the shires farming families founded the Oxley True Blues Orange Lodge: Thomas G. Johnston as master,[82] Thomas Mullin, deputy master, and George Donaldson, secretary with a lodge hall erected in 1885 on part of Thomas Johnston's holding at Sherwood.[7]

The Freemasons established the Hopeful Lodge at Corinda in 1896. This lodge met on the Monday nearest the full moon at Mr Dunlop's hall, the School of Arts, Corinda and in 1914, the lodge bought the former Methodist Church in Skew Street, Sherwood as a meeting place. The first Oddfellows lodge formed in the Sherwood Shire, the Pride of Oxley, met at Oxley from 1900. Just prior to World War 1, Manchester Unity had established the Loyal Sherwood Forest Lodge at Sherwood and in 1913 the Alliance Tent No. 63, by the Queensland District of the Independent Order of Rechabites was formed. The Alliance Tent met on alternate Monday evenings in the parish hall, Sherwood. In 1920, the Sherwood Oak Lodge, was also formed.[7]

Each lodge or tent paid out sickness benefits being medical fees and chemist prescriptions. The Oddfellows, Druids, and Rechabite Order's members, when off work because of illness, were assured of a minimum of £1 per week for 6 months. The central controlling bodies of these local Orders paid a minimum of £30 in funeral benefits. By 1920, the combined membership of fraternal lodges and friendly societies in the Sherwood Shire totaled 322.[7]

Sporting clubs

The Brisbane Golf Club, the first sporting club in the Sherwood Shire was organised in a meeting of city businessmen held in the A.M.P. chambers in 1896. The club built a 9-hole course at Chelmer between the railway line and river. The Brisbane Golf Club became the first golf club in Queensland.[83] To enlarge the playing area to 18 holes, the club moved from the shire to Yeerongpilly, where it is presently situated. The original clubhouse still stands on Honour Avenue opposite the Chelmer Railway Station.[7]

The Oxley Electorate Sailing Club when formed in 1902, chose the reach of the Brisbane River at Chelmer east as its sailing area.[84] The club catered for all classes of craft until the 1920s, when it limited competition to 14-foot sharpies. By 1921, senior office-bearers included Augustus Cecil Elphinstone of Corinda, representing the Oxley Electorate in the Queensland Legislative Assembly, and solicitors John Cannan junior and Arthur Baynes, both of Chelmer.[7]

Horse racing was introduced in the 1860s, on a course in the grounds of the Oxley hotel. Racing was intermittent, drawing entries from Ipswich and the Nerang and Logan River areas.[85] A 1910 picnic race programme consisted of foot races, swimming events in Oxley Creek. During World War 1, horse races were staged at Oxley in aid of the Red Cross.[7]

In the mid-1890s, a cricket club the Sherwood Forest Cricket Club, drew local support. The Corinda Cricket Club functioned briefly in the early 1900s and by 1920 another cricket club, the Sherwood Cricket Club, attracted players from the shire community. During 1921, the Western Suburbs Electorate Cricket Club entered the Queensland Cricket Associations fixtures with its territory embracing both the Taringa and Sherwood Shires.[86] Local players were Sherwood cinema owner Barney Cook,[87] and Corinda resident and city auctioneer, Roger Hartigan.[7]

Thomas Hall introduced athletics to the area in the early 1900s with neighbour, John Beal, an accountant in the Lands Department. Hall led a committee supporting the Oxley Electorate Amateur Athletic Club. The Chelmer Lacrosse Club after World War 1 entered two teams in the Brisbane competition.[7]

In 1919, two sporting clubs, the Graceville Croquet Club and the Graceville Bowls Club were formed. The women who founded the croquet club, initially played on the lawns of several ladies in the district but in 1920, the shire council granted the croquet players a lease on a portion of Graceville Memorial Park.[88] The formation of the Graceville Bowls Club attracted an initial membership of seventy. Sherwood resident, Chief Justice Sir Pope Cooper, served as foundation Patron.[89][7]

Since the 1890s there was an increased interest in tennis. This led to the rapid increase of tennis courts in the large allotments to the west of the railway, where social games were played among the middle class and their invited guests. Hardcourts on smaller residential allotments to the east of the railway were constructed. Between the two world wars, over 120 tennis courts were situated in the suburbs from Chelmer to Oxley. Sherwood had 37 courts, Graceville 31, Corinda 27, Chelmer 20, and Oxley, 9. Following World War 1, tennis enthusiasts formed and administered the Western Suburbs Tennis Association which from the 1920s, organized graded competitions between clubs situated in the Chelmer- Oxley area. It was customary for women to provide the afternoon tea and the men to pay for the balls used in the match.[7]

The Sherwood Boy Scouts, established in 1910 by James Knox-Dunn initially comprised a dozen boys aged between 12 and 17 being formed into patrols located between Chelmer and Oxley. The scout movement contained a moral code outlined by British Boer War hero, Robert Stephenson Smythe Baden-Powell, in his book 'Scouting for Boys'. This code expected boy scouts to do their duty to God, and to the King along with motivating regular church attendance. A re-organisation of the Sherwood scouts occurred after World War I where they met as a troop rather than in separate patrols. The adult supporters committee comprised the three local Protestant clergy, the Sherwood primary school head teacher and a prominent Corinda resident, Thomas Hall, who served as president.[90][7]

Those who supported the numerous and varied social activities, the most prominent and consistent was Thomas Murray Hall. His 30 years of community service embraced eleven local organizations.[7]

Military aspects

There was a negative response by local residents to a powder magazine established in the mid-1880s near the Brisbane River at Sherwood where ammunition was stored on behalf of the then Queensland Navy. This area was mostly on the river side of what is now known as Magazine Street in Sherwood. It was revealed that the magazine contained 6632 pounds of powder including filled cartridges, and 18,000 rounds of ammunition. The magazine continued to concern the local community until its removal during the World War I.[91][7]

During the Boer War in South Africa, two local volunteers, Sergeant Robert Edwin Berry and acting-Corporal John MacFarlane died during manoeuvres against the Boers in the Transvaal. The first war memorial in the shire was erected in the grounds of St. Matthew's church cemetery in their honour.

Since 1904, the Sherwood Shire Council developed parkland on the main road at Graceville. In 1919, the council designated this area a memorial park in commemoration of those who had died in World War 1. Two rows of trees, each tree remembering of one of the fallen, formed an avenue from the main road to a granite obelisk designed by Islay Bennett. The honour roll recorded the names of 51 servicemen and one nursing sister. The shire residents subscribed £255 towards the erection of the memorial with the collection organized by Ethel Lidgard. Lieutenant Maurice Little, severely wounded at Gallipoli, unveiled the memorial on 29 November 1920.[7][92]

On the corner of Ipswich and Oxley Roads, the Sherwood Shire Council erected a statue of an Australian soldier mounted on a pedestal as a memorial, where the names of fifteen servicemen from Oxley killed in action were inscribed. The shire council honoured two of these servicemen, Privates R. Price and M. Enright, by naming two nearby streets after them. It was unveiled on Saturday 12 February 1921 by the wife of Cecil Elphinstone, Member of the Legislative Assembly for Oxley. Today, the Oxley War Memorial sits on the crest of a ridge on the corner of Oxley Road and Bannerman Street in Oxley.

In 1919, six returned servicemen founded the Sherwood sub-branch of the Returned Soldiers and Sailors Imperial League of Australia, with Maurice Little as president.[93] It was one of several hundred sub-branches of the League formed throughout Australia, its national membership peaking at 114,700 by 1919.The League encouraged sub-branch membership to preserve the memory of those who had died in war, care for the needs of the sick and injured and their dependants, and to support one another on their return to civilian life.[7]

References

- ^ "Agency ID 1853, Stephens Divisional Board". Queensland State Archives. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ "Agency ID 9629, Sherwood Shire Council". Queensland State Archives. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ "Order in Council". Queensland Government Gazette. 26 September 1925. p. 125:1288.

- ^ "SUMMARY OF NEWS". The Brisbane Courier. National Library of Australia. 31 January 1901. p. 4. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ "Queensland Mayors and Shire Chairmen". The Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld. : 1866 - 1939). Brisbane, Qld.: National Library of Australia. 24 February 1906. p. 22. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ "Mayors and Chairmen of Councils Who Were Entertained Yesterday By Alderman Jolly". The Brisbane Courier. National Library of Australia. 1 October 1925. p. 9. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj Fones, Ralph (1 January 1993). "Suburban Conservatism in the Sherwood Shire, 1891-1920". UQ eSpace. The University of Queensland. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "THE SINKING OF THE FAIRY". Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald And General Advertiser. Queensland, Australia. 22 April 1875. p. 4. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "The 1893 flood". Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ "Thomas Boyland, Margaret Boyland". Archived from the original on 13 October 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "LAND SALE". The Courier (Brisbane). Vol. XVI, no. 1267. Queensland, Australia. 27 February 1862. p. 2. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "OBITUARY". The Brisbane Courier. No. 20, 702. Queensland, Australia. 30 May 1924. p. 4. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Morrison, A. A. "Henry Jordan (1818–1890)". Jordan, Henry (1818–1890). National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "THE SUGAR INTEREST AT OXLEY". The Queenslander. Vol. III, no. 119. Queensland, Australia. 16 May 1868. p. 10. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "OXLEY". The Week. Queensland, Australia. 1 June 1878. p. 22. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ a b "STARTED SERVICES IN TENT". The Telegraph. Queensland, Australia. 7 November 1935. p. 13 (LATE CITY CABLE NEWS). Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "CHURCH OF ENGLAND, OXLEY CREEK". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. XXIII, no. 3, 627. Queensland, Australia. 19 May 1869. p. 3. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "St Matthew's Anglican Church". Churches Australia. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ "Sherwood Presbyterian Church - Former". Churches Australia. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ "Obituary - James Samuel Hassall". Obituaries Australia. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ a b "OBITUARY". The Daily Mail. No. 7674. Queensland, Australia. 4 October 1926. p. 8. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "OXLEY". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. XXIV, no. 3, 862. Queensland, Australia. 19 February 1870. p. 6. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Personal and Anecdotal". Sunday Mail. No. 177. Queensland, Australia. 24 October 1926. p. 8. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "OBITUARY. MR. A. C. RAFF". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 29, 373. New South Wales, Australia. 25 February 1932. p. 13. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "DEATH OF MR. T. G. DEWAR". The Evening News. No. 3452. Queensland, Australia. 14 October 1932. p. 12. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c "Our heritage trail". Sherwood Arboretum. Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ Noble, Jennifer, "Joseph Tainton (1901–1981)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, archived from the original on 24 March 2023, retrieved 12 October 2023

- ^ a b "Former Sherwood School Head Dead". The Telegraph. Queensland, Australia. 22 September 1947. p. 4 (CITY FINAL LAST MINUTE NEWS). Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "MEMORIAL SERVICE AT SHERWOOD". The Brisbane Courier. Vol. LXI, no. 14, 507. Queensland, Australia. 12 July 1904. p. 4. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Age and invalid pensions". National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ "THE BAND OF HOPE MOVEMENT". The Canberra Times. Vol. 1, no. 63. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 5 August 1927. p. 1. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "James Samuel Hassall". Obituaries Australia. Australian National University. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "Sherwood Anglican Church". The Week. Vol. XCII, no. 2, 388. Queensland, Australia. 30 September 1921. p. 24. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "St Matthew's Anglican Church". Churches Australia. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Sherwood Uniting Church". Churches Australia. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "NEW CONVENT AT CORINDA". Daily Standard. No. 1291. Queensland, Australia. 29 January 1917. p. 4. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ ""THEN and NOW"". The Telegraph. Queensland, Australia. 20 May 1935. p. 7 (LATE CITY). Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Major A. J. Boyd, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, 2004, archived from the original on 13 October 2023, retrieved 12 October 2023

- ^ "HAPPY RETIREMENT". The Brisbane Courier. No. 23, 096. Queensland, Australia. 6 February 1932. p. 16. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Queensland School Readers". Education Queensland. Queensland Government. 14 April 2019. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "NEW PARK". Brisbane Courier. 21 November 1932. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Gill, J. C. H., "Walter Horatio Wilson (1839–1902)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, archived from the original on 9 June 2023, retrieved 12 October 2023

- ^ "Advertising". Telegraph. 19 November 1888. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ a b "Advertising". The Capricornian. Queensland, Australia. 2 August 1890. p. 16. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "James Tolson". Obituaries Australia. Australian National University. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "Corinda Station". Telegraph. 16 January 1889. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ "Destruction of the Indooroopilly Railway Bridge - 1893 Brisbane Flood". State Library Of Queensland. 5 February 2018. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "BRISBANE'S HISTORIC HOMES". The Queenslander. Queensland, Australia. 28 April 1932. p. 34. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Passing of the Pioneers". The Queenslander. Queensland, Australia. 18 February 1932. p. 9. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "1893 Brisbane Flood - Detailed History and Images". Brisbane History. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "Black Death in Queensland". State Library Of Queensland. 12 September 2008. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ Morley, Brendan (15 October 2009), Oxley, archived from the original on 13 October 2023, retrieved 12 October 2023

- ^ Oxley Station Estate G. T. Bell, Auctioneers., H.T. Bell [Lithographers], 1915, hdl:10462/deriv/252825, archived from the original on 13 October 2023, retrieved 12 October 2023

- ^ Morley, Brendan (15 October 2009), Graceville, archived from the original on 13 October 2023, retrieved 12 October 2023

- ^ Sherwood Park Estate : the cream of the district., H.T. James, 1913, hdl:10462/deriv/427696, archived from the original on 13 October 2023, retrieved 12 October 2023

- ^ The Sherwood Rise Estate : situated beside the Sherwood Railway Station., Warwick & Sapsford, 1887, hdl:10462/deriv/436438, archived from the original on 13 October 2023, retrieved 12 October 2023

- ^ Buckland, J. F. (1888), The township of Sherwood Estate, Warwick & Sapsford Lith., hdl:10462/deriv/280842, archived from the original on 13 October 2023, retrieved 12 October 2023

- ^ Shaw, F. G. (1880), Oatland's Estate To be sold by auction on the ground, on Saturday 21st. November at 2:30 p.m., Watson, Ferguson & Co., Litho., hdl:10462/deriv/18456, archived from the original on 13 October 2023, retrieved 12 October 2023

- ^ Township of Riverton on the Brisbane River at the Albert Siding of the S & W railway, known as Oxley Point / E. Hooker & Son, Auctioneers ; R.D. Graham & Son, Surveyors., Warwick & Sapsford [lithographer], 1880, hdl:10462/deriv/258859, archived from the original on 13 October 2023, retrieved 12 October 2023

- ^ "MR. R. D. NEILSON". The Week. Vol. C, no. 2, 604. Queensland, Australia. 20 November 1925. p. 8. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Death of Mr. J.F Bennett". Darling Downs Gazette. Vol. XLIII, no. 9, 854. Queensland, Australia. 2 August 1901. p. 2. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "PIONEER PASSES". The Telegraph. No. 16, 515. Queensland, Australia. 5 November 1925. p. 12 (5 O'CLOCK CITY EDITION). Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "BRISBANE'S HISTORIC HOMES". The Queenslander. Queensland, Australia. 5 May 1932. p. 34. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "BRISBANE'S HISTORIC HOMES". The Queenslander. Queensland, Australia. 17 September 1931. p. 35. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "MR. A. H. CHAMBERS". The Brisbane Courier. No. 22, 264. Queensland, Australia. 6 June 1929. p. 17. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Honourable Charles Stumm KC". Supreme Court Library Queensland. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "https://www.housedetective.com.au/lynnegrove". House Detective. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "HOME FOR OLD SOLDIERS". Courier-Mail. 22 February 1936. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "OBITUARY". Dalby Herald. 12 July 1938. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ Chisholm, A. H., "Henry William Coxen (1823–1915)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 11 December 2024

- ^ "BRISBANE'S HISTORIC HOMES". Queenslander Illustrated Weekly. 3 December 1931. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "IDEAL SITE". The Brisbane Courier. Queensland, Australia. 20 March 1933. p. 13. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "Our History". Montrose Therapy and Respite Services. 7 March 2020. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ "Ham and cheese please". History Out There. 14 September 2015. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "Brittains Bricks". Bricks in Queensland. 17 July 2014. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "Sojourn in Toowong – the Shirley Lahey Story". Toowong and District Historical Society. 20 January 2015. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "Mr. John Moffatt". Brisbane Courier. 10 February 1931. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "AN ARBORETUM". The Brisbane Courier. Queensland, Australia. 26 July 1924. p. 8. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "Corinda School of Arts" (PDF). ADFAS Brisbane. February 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "Sherwood | The Old Sherwood Picture Theatre Was The Heart Of The Community". www.eplace.com.au. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "Druid | Description, History, & Facts". Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "Our heritage trail". Sherwood Arboretum. Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "History". The Brisbane Golf Club. Archived from the original on 16 October 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "Club History". Oxley Sailing Club. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "OXLEY CREEK RACES". The Queenslander. Vol. I, no. 48. Queensland, Australia. 29 December 1866. p. 8. Retrieved 11 December 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Western Suburbs District Cricket Club History". Western Suburbs District Cricket Club. 30 October 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "DEATH OF MR. BARNEY COOK". The Telegraph. Queensland, Australia. 16 March 1944. p. 4 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved 11 December 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Welcome to the Graceville Croquet Club". Graceville Croquet Club. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "100 Years and counting - Graceville is thriving". Golf Queensland. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "OUR SCOUTS". The Brisbane Courier. No. 16, 450. Queensland, Australia. 1 October 1910. p. 14. Retrieved 11 December 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Sherwood Board". The Telegraph. No. 8, 876. Queensland, Australia. 2 May 1901. p. 7. Retrieved 11 December 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Maurice Little". Old Queensland Poetry. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ "Sub Branch History". Sherwood Indooroopilly RSL Sub Branch. Archived from the original on 15 October 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2024.