Severan dynasty

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Severan dynasty | ||

| Chronology | ||

193–211 |

||

with Caracalla 198–211 |

||

with Geta 209–211 |

||

211–217 |

||

211 |

||

Macrinus' usurpation 217–218 |

||

with Diadumenian 218 |

||

218–222 |

||

222–235 |

||

| Dynasty | ||

| Severan dynasty family tree | ||

|

All biographies |

||

| Succession | ||

|

||

The Severan dynasty, sometimes called the Septimian dynasty,[1] was an Ancient Roman imperial dynasty that ruled the Roman Empire between 193 and 235, during the Roman imperial period. The dynasty was founded by the emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211), who rose to power after the Year of the Five Emperors as the victor of the civil war of 193–197, and his wife, Julia Domna. After the short reigns and assassinations of their two sons, Caracalla (r. 211–217) and Geta (r. 211), who succeeded their father in the government of the empire, Julia Domna's relatives themselves assumed power by raising Elagabalus (r. 218–222) and then Severus Alexander (r. 222–235) to the imperial office.

The dynasty's control over the empire was interrupted by the joint reigns of Macrinus (r. 217–218) and his son Diadumenian (r. 218). The dynasty's women, including Julia Domna, the mother of Caracalla and Geta, and her nieces Julia Soaemias and Julia Mamaea, the mothers respectively of Elagabalus and Severus Alexander, and their own mother, Julia Maesa, were all powerful augustae and instrumental in securing their sons' imperial positions.

Although Septimius Severus restored peace following the upheaval of the late 2nd century, the dynasty was disturbed by highly unstable family relationships and constant political turmoil,[2] which foreshadowed the imminent Crisis of the Third Century. In particular, the discord between Caracalla and Geta and the tension between Elagabalus and Severus Alexander added to the turmoil.[3]

History

Septimius Severus (193–211)

Lucius Septimius Severus was born in Leptis Magna, then in the Roman province of Africa Proconsularis and now in Libya, into a Libyan-punic family of equestrian rank.[4] He rose through military service to consular rank under the later emperors of the Antonine dynasty. He married Syrian noblewoman Julia Domna and had two children with her: Caracalla and Geta. Julia Domna also held a prominent political role in government during her husband's reign. Severus was proclaimed emperor in 193 by his legionaries in Noricum during the political unrest that followed the death of Commodus and secured sole rule over the empire in 197 after defeating his last rival, Clodius Albinus, at the Battle of Lugdunum.

Severus fought a successful war against the Parthians, campaigned with success against barbarian incursions in Roman Britain and rebuilt Hadrian's Wall. In Rome, his relations with the Senate were poor, but he was popular with the commoners and with his soldiers, whose salary he raised. Starting in 197, his praetorian prefect, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus, was growing in influence, but he would be executed in 205. One of Plautianus's successors was the jurist Papinian, a relative of Julia Domna.

The Jews experienced more favorable conditions under the Severan dynasty. According to Jerome, both Septimius Severus and Antoninus "very greatly cherished the Jews."[5] Severus debased the Roman currency. Upon his accession he decreased the silver purity of the denarius from 81.5% to 78.5%, although the silver weight actually increased, rising from 2.40 grams to 2.46 grams. Nevertheless, the following year he debased the denarius again.The silver purity decreased from 78.5% to 64.5%—the silver weight dropping from 2.46 grams to 1.98 grams. In 196 he reduced the purity and silver weight of the denarius again, to 54% and 1.82 grams, respectively.[6]

Severus continued official persecution of Christians, who did not assimilate their beliefs to the official syncretistic creed. [citation needed]

Severus died while campaigning in Britain.[7] He was succeeded by his sons Caracalla and Geta, whom he had elevated as co-emperors in the years preceding his death. The growing hostility between the brothers was initially buffered by Julia Domna's mediation.

Caracalla (198–217)

The eldest son of Severus, he was born Lucius Septimius Bassianus in Lugdunum, Gaul. "Caracalla" was a nickname referring to the Gallic hooded tunic that he habitually wore even while he slept. Years before his father's death, Caracalla was proclaimed co-augustus with his father, and later his younger brother Geta. Conflict between the two culminated in the assassination of the latter less than a year after their father's death. Reigning alone, Caracalla was noted for lavish bribes to the legionaries and unprecedented cruelty by authorising numerous assassinations of perceived enemies and rivals. Caracalla was also indifferent to the full responsibilities of the empire during his reign and handed them over to his mother, Julia Domna, who took part in a provincial tour and military campaign and accompanied her son. He campaigned with indifferent success against the Alamanni. The Baths of Caracalla in Rome are the most enduring monument of his rule. He was assassinated en route to a campaign against the Parthians by a member of the Praetorian Guard.

Geta (209–211)

The younger son of Septimius Severus, Geta was made co-augustus alongside his father and older brother Caracalla. Unlike the much more successful joint reign of Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180) and his brother Lucius Verus (r. 161–169) the previous century, relations were hostile between the two Severan brothers after their father's death. Geta was assassinated in their mother's apartments by order of Caracalla, who then ruled as sole emperor.

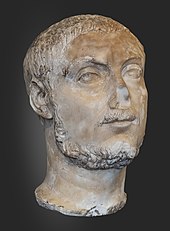

Interlude: Macrinus (217–218)

Marcus Opelius Macrinus was born in 164 at Caesarea in Mauretania (now Cherchell, Algeria). Although coming from a humble background not dynastically related to the Severan dynasty; he rose through the imperial household until, under Caracalla, he was made prefect of the Praetorian Guard. On account of the cruelty and the treachery of the emperor, Macrinus became involved in a conspiracy to kill him and ordered the Praetorian Guard to do so. On April 8, 217, Caracalla was assassinated travelling to Carrhae. Three days later, Macrinus was declared augustus.

His most significant early decision was to make peace with the Parthian Empire, but many thought that the terms were degrading to the Romans. However, his downfall was his refusal to award the pay and privileges promised to the eastern troops by Caracalla. He also kept those forces wintered in Syria, where they became attracted to the young Elagabalus. After months of mild rebellion by the bulk of the army in Syria, Macrinus took his loyal troops to meet the army of Elagabalus near Antioch. Despite a good fight by the Praetorian Guard, his soldiers were defeated. Macrinus managed to escape to Chalcedon but his authority was lost. He was betrayed and executed after a reign of only 14 months.

Marcus Opelius Diadumenianus (known as Diadumenian) was the son of Macrinus, born in 208. He was given the imperial rank of caesar in 217, when his father became augustus. After his father's defeat outside Antioch, he tried to escape east to Parthia but was captured and killed.

Elagabalus (218–222)

Elagabalus was born Varius Avitus Bassianus in 204 and became known later as Marcus Aurelius Antonius. The name "Elagabalus" followed the Latin nomenclature for the Syrian sun god Elagabal, of whom he had become a priest at an early age. Elagabal was represented by a large, dark rock called a baetyl. Elagabalus's grandmother, Julia Maesa, Julia Domna's sister and sister-in-law of Emperor Septimius Severus, arranged for the restoration of the Severan dynasty and persuaded soldiers from the Gallic Third Legion, which was stationed near Emesa, by using her enormous wealth[10] as well as the claim that Caracalla had slept with her daughter and that the boy was his bastard[11] to swear fealty to Elagabalus. He was later invited alongside his mother and daughters to the military camp, clad in imperial purple and crowned as emperor by the soldiers.

His reign in Rome has long been known for being outrageous although the historical sources are few and in many cases not to be fully trusted. He is said to have smothered guests at a banquet by flooding the room with rose petals, married his male lover (who was later referred to as the "empress's husband") and married a Vestal Virgin called Aquilia Severa. Dio suggests that he was transgender and offered large sums to the physician who could give him female genitalia.[12]

Seeing that her grandson's outrageous behaviour could mean the loss of power, Julia Maesa persuaded Elagabalus to accept his young cousin Severus Alexander as caesar (and thus the nominal future augustus). Alexander was popular with the troops, who increasingly objected to Elagabalus's behaviour. Jealous of this popularity, Elagabalus removed the title of caesar from his cousin, which enraged the Praetorian Guard. Elagabalus, his mother, and other advisors close to him were assassinated in a Praetorian Guard camp mutiny.

Alexander Severus (222–235)

Born Marcus Julius Gessius Bassianus Alexianus in around 208, Alexander was adopted as heir apparent by his slightly older and very unpopular cousin, Elagabalus, at the urging of Julia Maesa, who was the grandmother of both cousins and who had arranged for the emperor's acclamation by the Third Gallica Legion.

On March 6, 222, when Alexander was 14, a rumour went around the city's troops that Alexander had been killed, ironically triggering his ascension as emperor. Elagabalus was said to have initiated the rumour or attempted to murder Alexander.[13] The 18-year-old Elagabalus and his mother were taken from the palace, dragged through the streets, murdered and thrown in the river Tiber by the Praetorian Guard, which proclaimed Alexander Severus as Augustus.

Ruling from the age of 14 under the influence of his mother, Julia Avita Mamaea, Alexander restored to some extent the moderation that had characterised the rule of Septimius Severus. The rising strength of the Sasanian Empire (r. 226–651) heralded perhaps the greatest external challenge that Rome faced in the 3rd century. His prosecution of the war against a Germanic invasion of Gaul led to his overthrow by his own troops, whose regard the 27-year-old had lost during the affair.

His death was the epochal event beginning the troubled Crisis of the Third Century, where a succession of briefly-reigning military emperors, rebellious generals, and counter-claimants presided over governmental chaos, civil war, general instability and great economic disruption. He was succeeded by Maximinus Thrax (r. 235–238), the first of a series of weak emperors, each ruling on average only 2 to 3 years, which ended 50 years later with the Tetrarchy instituted in the reign of Diocletian (r. 284–305).

Women

The women of the Severan dynasty, beginning with Septimius Severus's wife Julia Domna, were notably active in advancing the careers of their male relatives. Other notable women who exercised power behind the scenes included Julia Maesa, sister of Julia Domna, and Maesa's two daughters Julia Soaemias, mother of Elagabalus, and Julia Avita Mamaea, mother of Severus Alexander. Also of interest, Publia Fulvia Plautilla, daughter of Gaius Fulvius Plautianus, the Prefect Commander of the Praetorian Guard, was married to but despised by Caracalla, who had her exiled and eventually executed.

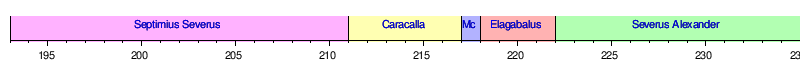

Dynastic timeline

See also

References

- ^ Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (2012). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. OUP Oxford. p. 1449. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8.

- ^ "Severan Dynasty · Arch for Septimius Severus · Piranesi in Rome". omeka.wellesley.edu. Retrieved 2022-04-08.

- ^ Scott, Andrew (May 2008). Change and discontinuity within the Severan dynasty: the case of Macrinus. New Brunswick, New Jersey, United States.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gall, Joël Le; Glay, Marcel Le (1992). "Chapitre III - Septime Sévère ou la « revanche d'Hannibal »". Peuples et Civilisations: 541–577. ISBN 978-2-13-044280-6.

- ^ Birley (1999), p. 135.

- ^ "Tulane University "Roman Currency of the Principate"". Archived from the original on 10 February 2001. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Birley (1999), pp. 170–187.

- ^ Mattingly & Sydenham, Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. IV, part I, p. 115.

- ^ Mattingly & Sydenham, Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. IV, part II, p. 43.

- ^ "The Severan Women". 15 September 2023.

- ^ Icks, Martijn (2011). The Crimes of Elagabalus: The Life and Legacy of Rome's Decadent Boy Emperor. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p. 11. ISBN 978-1848853621.

- ^ Dio 74:16:7 "He carried his lewdness to such a point that he asked the physicians to contrive a woman's vagina in his body by means of an incision, promising them large sums for doing so".

- ^ Cassius Dio 80.19-20, Herodian 5.8.5

Bibliography

- Anthony Birley., Septimius Severus: The African Emperor, Routledge, London, 1999. ISBN 0415165911

- Markus Handy, Die Severer und das Heer, Berlin, Verlag Antike, 2009 (Studien zur Alten Geschichte, 10).

- Harold Mattingly, Edward A. Sydenham, The Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. IV, part I, Pertinax to Geta, London, Spink & Son, 1936.

- Harold Mattingly, Edward A. Sydenham, C. H. V. Sutherland, The Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. IV, part II, Marcinus to Pupienus, London, Spink & Son, 1938.

- Simon Swain, Stephen Harrison and Jas Elsner (editors), Severan culture, Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Further reading

- Alföldy, Géza. 1974. "The Crisis of the Third Century as Seen by Contemporaries." Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 15:89–111.

- Benario, Herbert W. 1958. "Rome of the Severi." Latomus 17:712–722.

- Birley, Eric. 1969. "Septimius Severus and the Roman Army." Epigraphische Studien 8:63–82.

- Campbell, Brian. 2005. "The Severan Dynasty." In Cambridge Ancient History: The Crisis of Empire (A.D. 193–337). Edited by Alan K. Bowman, Peter Garnsey, and Averil Cameron, 1–27. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- De Blois, Lukas. 2003. "The Perception of Roman Imperial Authority in Herodian’s Work." In The Representation and Perception of Roman Imperial Power. Edited by Lukas De Blois, Paul Erdkamp, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn, and S. Mols, 148–156. Amsterdam: J. C. Gieben.

- De Sena, Eric C., ed. 2013. The Roman Empire During the Severan Dynasty: Case Studies in History, Art, Architecture, Economy and Literature. American Journal of Ancient History 6–8. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias.

- Langford, Julie. 2013. Maternal Megalomania: Julia Domna and the Imperial Politics of Motherhood. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

- Manders, Erika. 2012. Coining Images of Power: Patterns in the Representation of Roman Emperors on Imperial Coinage, A.D. 193–284. Leiden, The Netherlands, and Boston: Brill

- Moscovich, M. James. 2004. "Cassius Dio’s Palace Sources for the Reign of Septimius Severus." Historia 53.3: 356–368.

- Ward-Perkins, John Bryan. 1993. The Severan Buildings of Lepcis Magna: An Architectural Survey. London: Society for Libyan Studies.