Series and parallel circuits

Two-terminal components and electrical networks can be connected in series or parallel. The resulting electrical network will have two terminals, and itself can participate in a series or parallel topology. Whether a two-terminal "object" is an electrical component (e.g. a resistor) or an electrical network (e.g. resistors in series) is a matter of perspective. This article will use "component" to refer to a two-terminal "object" that participates in the series/parallel networks.

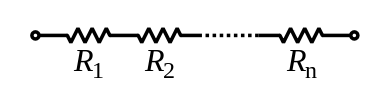

Components connected in series are connected along a single "electrical path", and each component has the same electric current through it, equal to the current through the network. The voltage across the network is equal to the sum of the voltages across each component.[1][2]

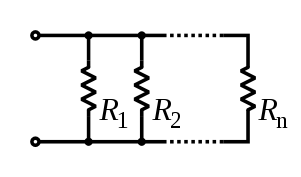

Components connected in parallel are connected along multiple paths, and each component has the same voltage across it, equal to the voltage across the network. The current through the network is equal to the sum of the currents through each component.

The two preceding statements are equivalent, except for exchanging the role of voltage and current.

A circuit composed solely of components connected in series is known as a series circuit; likewise, one connected completely in parallel is known as a parallel circuit. Many circuits can be analyzed as a combination of series and parallel circuits, along with other configurations.

In a series circuit, the current that flows through each of the components is the same, and the voltage across the circuit is the sum of the individual voltage drops across each component.[1] In a parallel circuit, the voltage across each of the components is the same, and the total current is the sum of the currents flowing through each component.[1]

Consider a very simple circuit consisting of four light bulbs and a 12-volt automotive battery. If a wire joins the battery to one bulb, to the next bulb, to the next bulb, to the next bulb, then back to the battery in one continuous loop, the bulbs are said to be in series. If each bulb is wired to the battery in a separate loop, the bulbs are said to be in parallel. If the four light bulbs are connected in series, the same current flows through all of them and the voltage drop is 3 volts across each bulb, which may not be sufficient to make them glow. If the light bulbs are connected in parallel, the currents through the light bulbs combine to form the current in the battery, while the voltage drop is 12 volts across each bulb and they all glow.

In a series circuit, every device must function for the circuit to be complete. If one bulb burns out in a series circuit, the entire circuit is broken. In parallel circuits, each light bulb has its own circuit, so all but one light could be burned out, and the last one will still function.

Series circuits

| Articles about |

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

Series circuits are sometimes referred to as current-coupled. The current in a series circuit goes through every component in the circuit. Therefore, all of the components in a series connection carry the same current.

A series circuit has only one path through which its current can flow. Opening or breaking a series circuit at any point causes the entire circuit to "open" or stop operating. For example, if even one of the light bulbs in an older-style string of Christmas tree lights burns out or is removed, the entire string becomes inoperable until the faulty bulb is replaced.

Current

In a series circuit, the current is the same for all of the elements.

Voltage

In a series circuit, the voltage is the sum of the voltage drops of the individual components (resistance units).

Resistance units

The total resistance of two or more resistors connected in series is equal to the sum of their individual resistances:

Here, the subscript s in Rs denotes "series", and Rs denotes resistance in a series.

Here, the subscript s in Rs denotes "series", and Rs denotes resistance in a series.

Conductance

Electrical conductance presents a reciprocal quantity to resistance. Total conductance of a series circuits of pure resistances, therefore, can be calculated from the following expression:

For a special case of two conductances in series, the total conductance is equal to:

Inductors

Inductors follow the same law, in that the total inductance of non-coupled inductors in series is equal to the sum of their individual inductances:

However, in some situations, it is difficult to prevent adjacent inductors from influencing each other as the magnetic field of one device couples with the windings of its neighbors. This influence is defined by the mutual inductance M. For example, if two inductors are in series, there are two possible equivalent inductances depending on how the magnetic fields of both inductors influence each other.

When there are more than two inductors, the mutual inductance between each of them and the way the coils influence each other complicates the calculation. For a larger number of coils the total combined inductance is given by the sum of all mutual inductances between the various coils including the mutual inductance of each given coil with itself, which is termed self-inductance or simply inductance. For three coils, there are six mutual inductances , , and , and . There are also the three self-inductances of the three coils: , and .

Therefore

By reciprocity, = so that the last two groups can be combined. The first three terms represent the sum of the self-inductances of the various coils. The formula is easily extended to any number of series coils with mutual coupling. The method can be used to find the self-inductance of large coils of wire of any cross-sectional shape by computing the sum of the mutual inductance of each turn of wire in the coil with every other turn since in such a coil all turns are in series.

Capacitors

Capacitors follow the same law using the reciprocals. The total capacitance of capacitors in series is equal to the reciprocal of the sum of the reciprocals of their individual capacitances:

Equivalently using elastance (the reciprocal of capacitance), the total series elastance equals the sum of each capacitor's elastance.

Switches

Two or more switches in series form a logical AND; the circuit only carries current if all switches are closed. See AND gate.

Cells and batteries

A battery is a collection of electrochemical cells. If the cells are connected in series, the voltage of the battery will be the sum of the cell voltages. For example, a 12 volt car battery contains six 2-volt cells connected in series. Some vehicles, such as trucks, have two 12 volt batteries in series to feed the 24-volt system.

Parallel circuits

If two or more components are connected in parallel, they have the same difference of potential (voltage) across their ends. The potential differences across the components are the same in magnitude, and they also have identical polarities. The same voltage is applied to all circuit components connected in parallel. The total current is the sum of the currents through the individual components, in accordance with Kirchhoff's current law.

Voltage

In a parallel circuit, the voltage is the same for all elements.

Current

The current in each individual resistor is found by Ohm's law. Factoring out the voltage gives

Resistance units

To find the total resistance of all components, add the reciprocals of the resistances of each component and take the reciprocal of the sum. Total resistance will always be less than the value of the smallest resistance:

For only two resistances, the unreciprocated expression is reasonably simple:

This sometimes goes by the mnemonic product over sum.

For N equal resistances in parallel, the reciprocal sum expression simplifies to: and therefore to:

To find the current in a component with resistance , use Ohm's law again:

The components divide the current according to their reciprocal resistances, so, in the case of two resistors,

An old term for devices connected in parallel is multiple, such as multiple connections for arc lamps.

Conductance

Since electrical conductance is reciprocal to resistance, the expression for total conductance of a parallel circuit of resistors is simply:

The relations for total conductance and resistance stand in a complementary relationship: the expression for a series connection of resistances is the same as for parallel connection of conductances, and vice versa.

Inductors

Inductors follow the same law, in that the total inductance of non-coupled inductors in parallel is equal to the reciprocal of the sum of the reciprocals of their individual inductances:

If the inductors are situated in each other's magnetic fields, this approach is invalid due to mutual inductance. If the mutual inductance between two coils in parallel is M, the equivalent inductor is:

If

The sign of depends on how the magnetic fields influence each other. For two equal tightly coupled coils the total inductance is close to that of every single coil. If the polarity of one coil is reversed so that M is negative, then the parallel inductance is nearly zero or the combination is almost non-inductive. It is assumed in the "tightly coupled" case M is very nearly equal to L. However, if the inductances are not equal and the coils are tightly coupled there can be near short circuit conditions and high circulating currents for both positive and negative values of M, which can cause problems.

More than three inductors become more complex and the mutual inductance of each inductor on each other inductor and their influence on each other must be considered. For three coils, there are three mutual inductances , and . This is best handled by matrix methods and summing the terms of the inverse of the matrix (3×3 in this case).

The pertinent equations are of the form:

Capacitors

The total capacitance of capacitors in parallel is equal to the sum of their individual capacitances:

The working voltage of a parallel combination of capacitors is always limited by the smallest working voltage of an individual capacitor.

Switches

Two or more switches in parallel form a logical OR; the circuit carries current if at least one switch is closed. See OR gate.

Cells and batteries

If the cells of a battery are connected in parallel, the battery voltage will be the same as the cell voltage, but the current supplied by each cell will be a fraction of the total current. For example, if a battery comprises four identical cells connected in parallel and delivers a current of 1 ampere, the current supplied by each cell will be 0.25 ampere. If the cells are not identical in voltage, cells with higher voltages will attempt to charge those with lower ones, potentially damaging them.

Parallel-connected batteries were widely used to power the valve filaments in portable radios. Lithium-ion rechargeable batteries (particularly laptop batteries) are often connected in parallel to increase the ampere-hour rating. Some solar electric systems have batteries in parallel to increase the storage capacity; a close approximation of total amp-hours is the sum of all amp-hours of in-parallel batteries.

Combining conductances

From Kirchhoff's circuit laws the rules for combining conductance can be deducted. For two conductances and in parallel, the voltage across them is the same and from Kirchhoff's current law (KCL) the total current is

Substituting Ohm's law for conductances gives and the equivalent conductance will be,

For two conductances and in series the current through them will be the same and Kirchhoff's Voltage Law says that the voltage across them is the sum of the voltages across each conductance, that is,

Substituting Ohm's law for conductance then gives, which in turn gives the formula for the equivalent conductance,

This equation can be rearranged slightly, though this is a special case that will only rearrange like this for two components.

For three conductances in series,

Notation

The value of two components in parallel is often represented in equations by the parallel operator, two vertical lines (∥), borrowing the parallel lines notation from geometry.

This simplifies expressions that would otherwise become complicated by expansion of the terms. For instance:

Applications

A common application of series circuit in consumer electronics is in batteries, where several cells connected in series are used to obtain a convenient operating voltage. Two disposable zinc cells in series might power a flashlight or remote control at 3 volts; the battery pack for a hand-held power tool might contain a dozen lithium-ion cells wired in series to provide 48 volts.

Series circuits were formerly used for lighting in electric multiple units trains. For example, if the supply voltage was 600 volts there might be eight 70-volt bulbs in series (total 560 volts) plus a resistor to drop the remaining 40 volts. Series circuits for train lighting were superseded, first by motor-generators, then by solid state devices.

Series resistance can also be applied to the arrangement of blood vessels within a given organ. Each organ is supplied by a large artery, smaller arteries, arterioles, capillaries, and veins arranged in series. The total resistance is the sum of the individual resistances, as expressed by the following equation: Rtotal = Rartery + Rarterioles + Rcapillaries. The largest proportion of resistance in this series is contributed by the arterioles.[3]

Parallel resistance is illustrated by the circulatory system. Each organ is supplied by an artery that branches off the aorta. The total resistance of this parallel arrangement is expressed by the following equation: 1/Rtotal = 1/Ra + 1/Rb + ... + 1/Rn. Ra, Rb, and Rn are the resistances of the renal, hepatic, and other arteries respectively. The total resistance is less than the resistance of any of the individual arteries.[3]

See also

- Anti-parallel (electronics)

- Combining impedances

- Current divider

- Equivalent impedance transforms

- Hydraulic analogy

- Network analysis (electrical circuits)

- Resistance distance

- Series-parallel duality

- Series-parallel partial order

- Series and parallel springs

- Topology (electrical circuits)

- Voltage divider

- Wheatstone bridge

- Y-Δ transform

References

- ^ a b c Resnick, Robert; Halliday, David (1966). "Chapter 32". Physics. Vol. I and II (Combined international ed.). Wiley. LCCN 66-11527. Example 1.

- ^ Smith, R. J. (1966). Circuits, Devices and Systems (International ed.). New York: Wiley. p. 21. LCCN 66-17612.

- ^ a b Costanzo, Linda S. Physiology. Board Review Series. p. 74.

Further reading

- Williams, Tim (2005). The Circuit Designer's Companion. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-6370-7.

- "Resistor combinations: How many values using 1K ohm resistors?". EDN magazine.

- Grotz, Bernhard (2018-01-04). "Strömungswiderstand". Mechanik der Flüssigkeiten (in German).