Secondary glaucoma

Secondary glaucoma is a collection of progressive optic nerve disorders associated with a rise in intraocular pressure (IOP) which results in the loss of vision. In clinical settings, it is defined as the occurrence of IOP above 21 mmHg requiring the prescription of IOP-managing drugs.[1] It can be broadly divided into two subtypes: secondary open-angle glaucoma and secondary angle-closure glaucoma, depending on the closure of the angle between the cornea and the iris. Principal causes of secondary glaucoma include optic nerve trauma or damage,[2] eye disease, surgery, neovascularization,[3] tumours[4] and use of steroid and sulfa drugs.[2] Risk factors for secondary glaucoma include uveitis,[1] cataract surgery[5] and also intraocular tumours.[5] Common treatments are designed according to the type (open-angle or angle-closure) and the underlying causative condition, in addition to the consequent rise in IOP. These include drug therapy, the use of miotics, surgery or laser therapy.[6]

Pathophysiology

Secondary glaucoma has different forms based on the varying underlying ocular conditions. These conditions result in an increase in IOP that manifests as secondary glaucoma.

Paediatric congenital cataract associated glaucoma

Based on the onset of secondary glaucoma in paediatric patients, it can be classified into early-stage and late-stage glaucoma cases. Early-stage secondary glaucoma, observed as angle-closure glaucoma, results from the blockage and inflammation of the peripheral anterior synechiae structure.[5] However, early-stage secondary glaucoma rarely occurs with the readily available prescription of anti-inflammatory medications. On the other hand, late-stage glaucoma is commonly associated with open-angle glaucoma but the mechanisms are currently unconfirmed. Yet, it is believed to be closely related to the onset of trabeculitis or vitreous toxicity.[5]

In paediatric congenital cataract patients under the age of two, cataract surgery is considered and frequently employed as the primary treatment. There are two types of therapeutic combination, primary and secondary lens implantation (IOL).[5] In primary IOL, cataract surgery is performed alongside immediate implantation of IOL. However, in secondary IOL implantation, the patient is prescribed aphakic glasses or contact lenses till the implantation of IOL after a varied period of time between a few months or years. Primary IOL implantation is observed to significantly reduce and avoid the occurrence of secondary glaucoma in paediatric patients under the age of two.[5]

Herpetic anterior uveitis associated glaucoma

In patients diagnosed with herpetic anterior uveitis, elevated IOP and secondary glaucoma are often detected. This is due to two main reasons, the blockage of vitreous flow resulting from inflammation in the structures of the trabecular meshwork, and the sedimentation of inflamed cells. Specifically for viral anterior uveitis, patients with IOP levels above 30 mmHg are often suffer from secondary glaucoma caused by cytomegalovirus.

Other forms of secondary glaucoma

- Pigmentary glaucoma: In pigmentary glaucoma, the obstruction of the trabecular meshwork caused by iris pigment release results in increased IOP. This release in iris pigment occurs as a result of the interaction of a flaccid iris with the zonular fibres.[2]

- Exfoliation syndrome: Exfoliation syndrome is a classic cause of secondary open-angle glaucoma, a common symptom of exfoliation syndrome is a cloudy layer on the anterior lens capsule.[2]

- Aphakic and pseudophakic glaucoma: Aphakic glaucoma is a common side-effect of cataract surgery which causes an increase in IOP.[2]

- Corticosteroid-induced glaucoma: Corticosteroids is a risk factor for the development of secondary glaucoma, as there had been increased IOP observed as a drug side-effect.[2]

- Post-traumatic glaucoma: Trauma to the eye is often observed to cause secondary glaucoma. The incidence is notably higher in populations with increased levels of physical activity.[2]

- Ghost-cell glaucoma: Ruptured red blood cells will release haemoglobin in the form of Heinz bodies, which are potent in increasing the IOP level.[2]

- Inflammatory glaucoma: The inflammatory reaction will affect the drainage of aqueous humour in the eye, causing an increase in IOP.[2]

- Glaucoma associated with ocular tumours: Although each tumour subtype has its own mechanism in causing secondary glaucoma, the general cause is the restriction of the meshwork resulting in the obstruction of aqueous humour flow.[2]

- Increased episcleral venous pressure: According to the Goldmann equation, the relationship between episcleral venous pressure (EVP) is directly proportional to the IOP. Therefore, an increase in the EVP will result in an increase in IOP.[2]

- Neovascular glaucoma: As a consequence of neovascularisation, or the formation of new blood vessels and supporting connective structures, there is blockage of the anterior chamber angle. This leads to elevation of IOP causing neovascular glaucoma.[3]

Epidemiology

The overall prevalence of secondary glaucoma across China between 1990 and 2015 was reported to be 0.15%, lower than the overall estimates for East Asia (0.39%).[7]

Varying forms of secondary glaucoma

Pigmentary glaucoma has lower incidence in Black and Asian populations, due to their characteristically thicker irises that result in a lower likelihood of pigment release, as compared to the White populations.[2] Incidence of exfoliation syndrome-caused secondary glaucoma is estimated to be approximately 10% of the glaucoma patient population in the United States and over 20% of the patient population in Iceland and Finland.[2]

In populations above the age of 40, neovascular glaucoma has a prevalence of 0.4% worldwide.[8] The incidence of pigmentary glaucoma decreases with age while in exfoliation syndrome the incidence increases with age.[2] However, given the derived nature of secondary glaucoma, there may be no significant association between age, ethnicity or gender and the prevalence of the condition.[7]

Secondary glaucoma indicated after congenital cataract surgery is found between 6 and 24% of the cases noted, whereas, secondary glaucoma caused by primary IOL implantation was observed as 9.5%.[5] Additionally, for patients with aphakia and secondary IOL implantation, 15.1% of the cases were determined.[5] The incidence risk in primary IOL implantation in children with cataract in both eyes is lower than secondary IOL implantation and aphakic condition. However, this difference is not observed in the general population and populations with cataract in one eye.[5]

Due to lack of concrete and specific epidemiological evidence, further research is required to accurately estimate the prevalence of secondary glaucoma and its subtypes.[7]

Risk factors

In general, elevated IOP is a major risk factor in the development of secondary glaucoma. However, there are several risk factors contributing to the fluctuation in IOP levels.

Uveitis

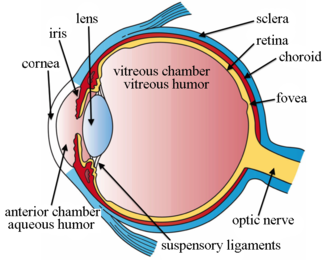

Secondary glaucoma is commonly associated with uveitis.[9] Uveitis is the inflammation of the uvea, a middle layer tissue of the eye consisting of the ciliary body, choroid and iris. Various causes have been identified as potential risk factors contributing to the occurrence of secondary glaucoma. These include viral anterior uveitis due to cytomegalovirus infection, and herpetic anterior uveitis caused by herpes simplex virus. The observed pathophysiology of secondary glaucoma in uveitis is found to be linked to the increase and fluctuation of IOP. Inflammation of eye tissues contributes to the blockage of IOP produced in the ciliary body. This results in the accumulation of aqueous and thus elevated IOP, which is a common risk factor for the progression of secondary glaucoma.[1]

Paediatric congenital cataract surgery

Paediatric congenital cataract surgery is also identified as a risk factor for the progression of secondary glaucoma.[10] Cataract is an ocular disease, identified by the progressive clouding of the lens. Surgical procedures are often employed to replace the lens and allow for clear vision. However, there is an increased risk of secondary glaucoma development in children due to the secondary IOL implantation procedure.[10] The increased inflammatory sensitivity in the anterior chamber angle may contribute to the risks of secondary glaucoma.[5]

Intraocular tumour

Intraocular tumours (uveal and retinal tumours) are also found to be closely associated with the development of secondary glaucoma. The pathophysiology of secondary glaucoma in these cases is affected by the type of tumour, location and other tumour-associated factors. Among the many subtypes of uveal tumours, secondary glaucoma is the most prominent among patients with trabecular meshwork iris melanoma.[4] The blockage of vitreous flow due to inflammation in the structures of the trabecular meshwork is also observed in herpetic anterior uveitis patients. In addition to this, angle invasion[4] is a mechanism that is observed to contribute greatly to the development of secondary glaucoma in patients with iris tapioca melanoma, iris lymphoma, choroidal melanoma, and medulloepithelioma.

Treatment and management

Pharmacological interventions

Miotic drugs are a class of cholinergic drugs that are frequently employed in the treatment and management of all types of glaucoma.[11][12] These drugs stimulate the contraction of the pupil causing the iris to pull away from the trabecular meshwork.[2][12] Consequently, the normal drainage of the aqueous humour is restored, relieving IOP. In addition to causing a direct effect on IOP, these drugs are applied to reduce pigment release (from the iris pigment epithelium) in the treatment of pigmentary glaucoma.[2] Despite the advantages, the widespread use of miotic drugs is limited by its associated side effects. There is an increased risk of development of posterior synechiae in glaucoma secondary to exfoliation syndrome and ocular trauma.[2] Other side effects include increased risk of miosis-induced headaches, blurred vision, retinal detachment and damage to the blood-aqueous barrier.[2]

Alternative drugs which can reduce the synthesis of aqueous humour, called aqueous suppressants, or increase the drainage of aqueous humour emerged as effective first-line treatments.[2][6] Aqueous suppressants include beta-blockers, alpha-agonists and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. They are particularly effective in treating corticosteroid, uveitic, aphakic, pseudophakic, ghost-cell and post-traumatic glaucoma.[2] Prostaglandin analogues increase aqueous drainage and are thus used in the reduction of IOP.[6] There are contradictory findings regarding the occurrence of prostaglandin analogue mediated side effects in the treatment of uveitic glaucoma. It was previously identified that the side effects comprise damage to the blood-aqueous barrier, cystoid macular oedema, risk of developing anterior uveitis and recurrence of keratitis caused by herpes simplex virus.[6] However, current scientific evidence only supports the reactivation of herpes simplex keratitis among the other side effects.[6]

In uveitic and inflammatory glaucoma, reduction in inflammation is a critical step during the treatment and management process. This is commonly done using corticosteroids coupled with immunosuppressants.[6] Steroidal treatment is also used in management of aphakic, pseudophakic, and post-traumatic glaucoma. Inflammatory glaucoma may further be treated using cycloplegics, a class of drugs that treats pain, ciliary spasm, uveoscleral tract blockage and disrupted blood-aqueous barrier linked with this form of glaucoma.[2] While some studies recommend the use of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor drugs for inhibition of neovascularization in neovascular glaucoma, there is a lack of substantial evidence for the effectiveness of this treatment method.[3]

Laser therapy

Among different laser therapies, laser peripheral iridotomy and laser trabeculoplasty are the most common procedures for secondary glaucoma. Both methods involve creating new outlets for the aqueous humour to flow out of, effectively reducing the IOP. In peripheral laser iridotomy, the opening is created in the iris tissue while in trabeculoplasty, this opening is made in the trabecular meshwork.[13] Further, there are two types of laser trabeculoplasty: argon laser trabeculoplasty and selective laser trabeculoplasty.[6]

Laser peripheral iridotomy has high efficacy in the treatment of pigmentary glaucoma. Argon laser trabeculoplasty is effective in the management of corticosteroid and pigmentary glaucoma.[2] However, this is often contraindicated due to high rates of failure in patients with uveitic glaucoma.[6] For uveitic glaucoma, treatment with selective laser trabeculoplasty is associated with fewer adverse effects and risks of failure.[6]

Surgical treatment

Surgical procedures are effective in cases where pharmacological management is not successful or suitable. Such methods work by facilitating aqueous outflow through the modification of the obstructing trabecular meshwork using trabeculectomy, goniotomy, non-penetrating deep sclerectomy or canaloplasty. Alternatively, introduction of new drainage pathways may also be achieved by the implantation of glaucoma shunts or glaucoma drainage devices.[6]

Trabeculectomy is held as the gold standard for surgical management of glaucoma. Studies indicate that treatment of uveitic glaucoma using trabeculectomy with antimetabolites administration has a high success rate of 62%-81%.[6] Thus, it is also commonly used in the treatment of pigmentary glaucoma.

Drainage tube implants are also implicated in treatment of uveitic and inflammatory glaucoma.[2][6]

Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery is performed in order to overcome the risks and adverse effects associated with conventional surgical procedures. However, there are limited studies testing the efficacy of utilising this type of surgery for the treatment of uveitic glaucoma.[6]

In addition to the direct reduction of IOP, surgical procedures are used to remove blood, viscoelastic fluid and debris in glaucoma caused by cataract extraction and ocular trauma. They may also be utilized to remove depot steroids in corticosteroid glaucoma and ghost cells from the vitreous humour in ghost-cell glaucoma through a procedure known as vitrectomy.[2]

References

- ^ a b c Hoeksema, Lisette; Jansonius, Nomdo M.; Los, Leonoor I. (September 2017). "Risk Factors for Secondary Glaucoma in Herpetic Anterior Uveitis". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 181: 55–60. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2017.06.013. PMID 28666730. S2CID 7188206.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Secondary open-angle glaucomas", Atlas of Glaucoma, CRC Press, pp. 151–166, 2007-02-13, doi:10.3109/9780203007204-16, ISBN 978-0-429-21415-8, retrieved 2021-04-01

- ^ a b c Simha, Arathi; Aziz, Kanza; Braganza, Andrew; Abraham, Lekha; Samuel, Prasanna; Lindsley, Kristina B (2020-02-06). "Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for neovascular glaucoma". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (2): CD007920. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007920.pub3. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 7003996. PMID 32027392.

- ^ a b c Camp, David A.; Yadav, Prashant; Dalvin, Lauren A.; Shields, Carol L. (March 2019). "Glaucoma secondary to intraocular tumors: mechanisms and management". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 30 (2): 71–81. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000550. ISSN 1040-8738. PMID 30562240. S2CID 56476426.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Zhang, Shuo; Wang, Jiaxing; Li, Ying; Liu, Ye; He, Li; Xia, Xiaobo (2019-04-01). "The role of primary intraocular lens implantation in the risk of secondary glaucoma following congenital cataract surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS ONE. 14 (4): e0214684. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1414684Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0214684. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6443152. PMID 30933995.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Kesav, Natasha; Palestine, Alan G.; Kahook, Malik Y.; Pantcheva, Mina B. (July–August 2020). "Current management of uveitis-associated ocular hypertension and glaucoma". Survey of Ophthalmology. 65 (4): 397–407. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.12.003. ISSN 1879-3304. PMID 31816329. S2CID 209166367.

- ^ a b c Song, Peige; Wang, Jiawen; Bucan, Kajo; Theodoratou, Evropi; Rudan, Igor; Chan, Kit Yee (December 2017). "National and subnational prevalence and burden of glaucoma in China: A systematic analysis". Journal of Global Health. 7 (2): 020705. doi:10.7189/jogh.07.020705. ISSN 2047-2978. PMC 5737099. PMID 29302324.

- ^ Chen, Monica F; Kim, Carole H; Coleman, Anne L (2019-03-10). "Cyclodestructive procedures for refractory glaucoma". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (3): CD012223. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd012223.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6409080. PMID 30852841.

- ^ Pohlmann, Dominika; Pahlitzsch, Milena; Schlickeiser, Stephan; Metzner, Sylvia; Lenglinger, Matthias; Bertelmann, Eckart; Maier, Anna-Karina B.; Winterhalter, Sibylle; Pleyer, Uwe (2020-02-24). Awadein, Ahmed (ed.). "Virus-associated anterior uveitis and secondary glaucoma: Diagnostics, clinical characteristics, and surgical options". PLOS ONE. 15 (2): e0229260. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1529260P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0229260. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7039515. PMID 32092116.

- ^ a b Swamy, B N; Billson, F; Martin, F; Donaldson, C; Hing, S; Jamieson, R; Grigg, J; Smith, J E H (2007-12-01). "Secondary glaucoma after paediatric cataract surgery". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 91 (12): 1627–1630. doi:10.1136/bjo.2007.117887. ISSN 0007-1161. PMC 2095522. PMID 17475699.

- ^ Clinical glaucoma care : the essentials. John R. Samples, Paul N. Schacknow. New York. 2014. ISBN 978-1-4614-4172-4. OCLC 868922426.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Shiroma, Lineu O; Costa, Vital P (2015), "Parasympathomimetics", Glaucoma, Elsevier, pp. 577–582, doi:10.1016/b978-0-7020-5193-7.00056-x, ISBN 978-0-7020-5193-7, retrieved 2021-04-01

- ^ Michelessi, Manuele; Lindsley, Kristina (2016-02-12). "Peripheral iridotomy for pigmentary glaucoma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (9): CD005655. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005655.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 5032906. PMID 26871761.