Scarp retreat

Scarp retreat is a geological process through which the location of an escarpment changes over time. Typically the cliff is undermined, rocks fall and form a talus slope, the talus is chemically or mechanically weathered and then removed through water or wind erosion, and the process of undermining resumes. Scarps may retreat for tens of kilometers in this way over relatively short geological time spans, even in arid locations.

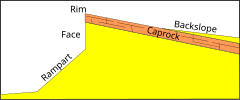

Scarp profiles

A scarp is a line of cliffs that has usually been formed by faulting or erosion. If it is protected by a strong caprock, or if it contains vertical fractures, it may retain its steep profile as it retreats.[1] Scarps in dry climates typically have a near-vertical upper face, that may account for 10% - 75% of the total height, with a talus-covered sloping rampart forming the lower section. The caprock is undermined as the rampart and face are eroded, and eventually a section collapses.[1] A strong caprock will typically create a relatively high cliff, since more undermining is needed to cause it to fail.[2] Other factors determining how easily a cliff will fail are the bedding and jointing, direction of dip and thickness of the caprock. A thin caprock will result in low cliffs that retreat quickly.[3]

However, a caprock is not essential for scarp retreat to occur as higher humidity and weathering at the foot ensures erosion at the foot drives (or keeps up with) the erosion of the free face.[4][5]

Mechanism

The most common way in which a scarp retreats is through rockfall, where individual blocks calve from the cliff or large sections of the cliff face collapse at once. In some high-energy situations, much of the rock may be powdered in a rockfall and easily eroded. Generally, though, the fallen debris must be weathered and the rampart eroded before scarp retreat can continue.[6] Mechanical and chemical weathering followed by wind erosion may operate in arid regions, where cliffs may retreat for long distances.[1] In such regions, large areas of shale badlands may be left behind as the scarp retreats.[3] Erosion may be caused by the sea where the scarp runs along a coast, or by streams in humid areas.[1]

Rate of retreat

The rate of retreat depends on the types of rock and the factors causing erosion. A study published in 2006 determined that the rate of scarp retreat in the Colorado Plateau today varies from 0.5 to 6.7 kilometres (0.31 to 4.16 mi) per million years depending on the thickness and resistance to erosion of the caprock.[7] Retreat of the Great Escarpment in Australia along the river valleys in the New England region appears to be progressing at about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) per million years.[8] A study of cuesta scarp retreat in southern Morocco showed an average rate of 1.3 kilometres (0.81 mi) per million years in areas with thin conglomerate caprocks. Where there were thicker, more resistant limestone caprocks the rate of retreat was slower, about 0.5 kilometres (0.31 mi) per million years.[9]

Examples

The Colorado Plateau has a cuesta scarp topography, consisting of slightly deformed strata of alternating harder and softer rocks. The climate has been mostly dry throughout the Cenozoic.[7] The conspicuous scarps on the plateau have massive sandstone caps over easily weathered rock such as shale. Freeze-thaw and groundwater sapping contribute to scarp retreat in this region.[10]

The Drakensberg mountains in South Africa are capped by a layer of Karoo basalts about 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) thick, which overlay Clarens formation sandstones. They have long been considered a classic example of a landform created by scarp retreat following continental break-up, with the retreat controlled by an inland drainage divide. However, they have inland-facing scarps as well as seaward-facing scarps, so factors other than continental break-up have contributed to their formation. A 2006 paper argued that surface process models may be inadequate in explaining rates of scarp retreat, which can also be greatly affected by the types of rock encountered as the scarp retreats, and by other factors such as climate, tectonic processes and possibly plant cover.[11]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d Chorley, Schumm & Sugden 1985, p. 273.

- ^ Chorley, Schumm & Sugden 1985, p. 273-274.

- ^ a b Chorley, Schumm & Sugden 1985, p. 274-275.

- ^ Twidale, C.R. (2007). "Backwearing of slopes - the development of an idea". Revista C & G. 21 (1–2): 135–146.

- ^ King, Lester (1968). "Scarps and Tablelands". Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie. 12: 114–115.

- ^ Parsons 2009, p. 202.

- ^ a b Schmidt 1989.

- ^ Johnson 2009, p. 205.

- ^ Schmidt 1988.

- ^ Parsons 2009, p. 203.

- ^ Moore & Blenkinsop 2006.

Sources

- Chorley, Richard J.; Schumm, Stanley Alfred; Sugden, David E. (1985). Geomorphology. Taylor & Francis. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-416-32590-4. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- Johnson, David (2009-11-04). The Geology of Australia. Cambridge University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-521-76741-5. Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- Moore, Andy; Blenkinsop, Tom (December 2006). "Scarp retreat versus pinned drainage divide in the formation of the Drakensberg escarpment, southern Africa" (PDF). South African Journal of Geology. 109 (4): 599–610. Bibcode:2006SAJG..109..599M. doi:10.2113/gssajg.109.4.599. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- Parsons, Anthony J. (2009-01-01). Geomorphology of Desert Environments. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-5719-9. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- Schmidt, Karl-Heinz (1988). "Rates of scarp retreat: A means of dating Neotectonic activity". The Atlas System of Morocco. Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences. Vol. 15. pp. 445–462. doi:10.1007/bfb0011604. ISBN 978-3-540-19086-8.

- Schmidt, Karl-Heinz (March 1989). "The significance of scarp retreat for cenozoic landform evolution on the Colorado Plateau, U.S.A.". Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 14 (2): 93–105. Bibcode:1989ESPL...14...93S. doi:10.1002/esp.3290140202.