Sayf al-Dawla

| Sayf al-Dawla سيف الدولة | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Emir of Aleppo | |||||

| Reign | 945–967 | ||||

| Predecessor | Uthman ibn Sa'id al-Kilabi (as Ikhshidid governor) | ||||

| Successor | Sa'd al-Dawla | ||||

| Born | 22 June 916 | ||||

| Died | 8 February 967 (aged 50) Aleppo, Abbasid Caliphate | ||||

| Burial | Mayyafariqin (now Silvan, Diyarbakır, Turkey) | ||||

| Issue | Sa'd al-Dawla | ||||

| |||||

| Tribe | Banu Taghlib | ||||

| Dynasty | Hamdanid | ||||

| Father | Abdallah ibn Hamdan | ||||

| Religion | Twelver Shi'ism | ||||

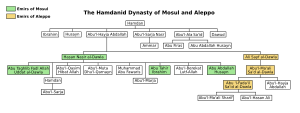

ʿAlī ibn ʾAbū'l-Hayjāʾ ʿAbdallāh ibn Ḥamdān ibn Ḥamdūn ibn al-Ḥārith al-Taghlibī[a] (Arabic: علي بن أبو الهيجاء عبد الله بن حمدان بن الحارث التغلبي, 22 June 916 – 8 February 967), more commonly known simply by his honorific of Sayf al-Dawla (سيف الدولة, lit. 'Sword of the Dynasty'), was the founder of the Emirate of Aleppo, encompassing most of northern Syria and parts of the western Jazira.

The most prominent member of the Hamdanid dynasty,[2] Sayf al-Dawla originally served under his elder brother, Nasir al-Dawla, in the latter's attempts to establish his control over the weak Abbasid government in Baghdad during the early 940s CE. After the failure of these endeavours, the ambitious Sayf al-Dawla turned towards Syria, where he confronted the ambitions of the Ikhshidids of Lower Egypt to control the province. After two wars with them, his authority over northern Syria, centred at Aleppo, and the western Jazira, centred at Mayyafariqin, was recognized by the Ikhshidids and the Abbasid caliph. A series of tribal rebellions plagued Sayf al-Dawla's realm until 955, but he overcame them and maintained the allegiance of the most important of the nomadic Bedouins.

Sayf al-Dawla is well known for his role in the Arab–Byzantine wars, facing a resurgent Byzantine Empire that in the early 10th century had begun to advance into the Muslim-controlled territories on its eastern border. In this struggle against a much more numerous and well-resourced enemy, Sayf al-Dawla launched raids deep into Byzantine territory and scored a few successes, for which he was widely celebrated in the Muslim world. The Hamdanid ruler generally held the upper hand until 955. After that, the new Byzantine commander, Nikephoros Phokas, and his lieutenants spearheaded a sustained offensive that broke Hamdanid power. The Byzantines annexed Cilicia, and even occupied Aleppo itself briefly in 962. Sayf al-Dawla's final years were marked by military defeats, his own growing disability as a result of disease, and a decline in his authority that led to revolts by some of his closest lieutenants. He died in early 967, leaving a much weakened realm, which by 969 had lost Antioch and the Syrian littoral to the Byzantines and had become a Byzantine tributary.

Sayf al-Dawla's court at Aleppo was the centre of a vibrant cultural life, and the literary cycle he gathered around him, including the great al-Mutanabbi, helped ensure his fame for posterity. At the same time, his domains suffered under an oppressive taxation regime to sustain the army. The Hamdanid ruler actively promoted Shi'a Islam in his domains, and under his rule, the Bedouin rose in importance, resulting in the establishment of the Mirdasid dynasty in Aleppo in 1024.

Life

Origin and family

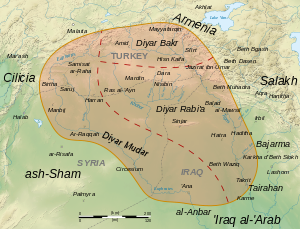

Sayf al-Dawla was born on 22 June 916 (17 Dhu al-Hijja 303 AH), although some sources give 914,[3][4] as Ali ibn Abdallah, the second son of Abdallah Abu'l-Hayja ibn Hamdan (died 929), son of Hamdan ibn Hamdun ibn al-Harith, who gave his name to the Hamdanid dynasty.[4][2] The Hamdanids were a branch of the Banu Taghlib, an Arab tribe resident in the area of the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia) since pre-Islamic times.[5]

The Taghlib had long been prominent in the area of Mosul, and came to control both the city and its environs following the so-called 'Anarchy at Samarra' (861–870),[5] a period during which the Abbasid Caliphate's metropolitan province of Iraq was engulfed in civil wars among the Abbasid elites. With the caliphal government's authority weakened, the provinces saw the rise of local strongmen, autonomous regional dynasties and anti-Abbasid rebels.[6] As Abbasid power revived in the late 9th century, the caliphal government tried to impose firmer control over the province. Hamdan ibn Hamdun was one of the most determined Taghlibi leaders in opposing this. In his effort to fend off the Abbasids, he secured the alliance of the Kurds living in the mountains north of Mosul, which would be of considerable importance in his family's later fortunes. Family members intermarried with Kurds, who were also prominent in the Hamdanid military.[2][7][8] Although the Hamdanids are generally regarded by modern historians as being pro-Shi'a, the division betwean Shi'a and Sunni Islam was not yet solidified, and historian Hugh Kennedy emphasizes that this does not apper to have affected their politics, allying with or fighting against both Shi'a and Sunni polities according to their momentary interests.[9]

Hamdan was defeated by the Abbasids in 895 and imprisoned with his relatives, but his son Husayn ibn Hamdan secured the family's future. He raised troops for the caliph among the Taghlib in exchange for tax remissions, and established a commanding influence in the Jazira by acting as a mediator between the Abbasid authorities and the Arab and Kurdish population. This strong local base allowed the family to survive its often strained relationship with the central Abbasid government in Baghdad during the early 10th century.[2][10] Husayn was a successful general, distinguishing himself against Kharijite rebels in the Jazira and the Tulunids of Egypt, but was disgraced after supporting the failed usurpation of the throne by the Abbasid prince Ibn al-Mu'tazz in 908. Husayn's younger brother Ibrahim was governor of Diyar Rabi'a (the province around Nasibin) in 919 and after his death in the next year he was succeeded by another brother, Dawud.[2][9] Ali's father, Abdallah, served as emir (governor) of Mosul in 905/6–913/4, and was repeatedly disgraced and rehabilitated, until re-assuming control of Mosul in 925/6. Enjoying firm relations with the powerful Abbasid commander-in-chief Mu'nis al-Muzaffar, he later played a leading role in the short-lived usurpation of al-Qahir against Caliph al-Muqtadir in 929, and was killed during its suppression.[11][12]

Despite the coup's failure and his death, Abdallah had been able to consolidate his control over Mosul, becoming the virtual founder of a Hamdanid-ruled emirate there. During his long absences in Baghdad in his final years, Abdallah relegated authority over Mosul to his eldest son, al-Hasan, the future Nasir al-Dawla. After Abdallah's death, al-Hasan's position in Mosul was challenged by his uncles, and it was not until 935 that he was able to secure confirmation by Baghdad of his control over Mosul and the entire Jazira up to the Byzantine frontier.[13][14]

Early career under Nasir al-Dawla

The young Ali began his career under his brother. In 936, al-Hasan invited Ali to his service, promising him the governorship of Diyar Bakr (the region around Amida) in exchange for his help against Ali ibn Ja'far, the rebellious governor of Mayyafariqin. Ali was successful in preventing Ibn Ja'far from receiving the assistance of his Armenian allies, and also secured control over the northern parts of the neighbouring province of Diyar Mudar after subduing the Bedouin (nomadic) Qaysi tribes of the region around Saruj.[8] From this position, he also launched expeditions to aid the Muslim emirates of the Byzantine frontier zone (the Thughur) against the advancing Byzantines, and intervened in Armenia to reverse growing Byzantine influence (see below).[15]

In the meantime, al-Hasan became involved in the intrigues of the Abbasid court. Since the murder of al-Muqtadir in 932, the Abbasid government had all but collapsed, and in 936 the powerful governor of Wasit, Muhammad ibn Ra'iq, assumed the title of amir al-umara ('commander of commanders') and with it de facto control of the Abbasid government. Caliph al-Radi was reduced to a figurehead role, and the extensive old civil bureaucracy was drastically reduced both in size and power.[16] Ibn Ra'iq's position was anything but secure, however, and soon a convoluted struggle for control of the office of amir al-umara, and the Caliphate with it, broke out among the local rulers and the Turkic military chiefs, which ended in 946 with the victory of the Buyids.[17]

Al-Hasan initially supported Ibn Ra'iq, but in 942 he had him assassinated and secured for himself the post of amir al-umara, receiving the honorific (laqab) of Nasir al-Dawla ('Defender of the Dynasty'), by which he is best known to posterity. The Baridis, a local family of Basra, who also desired control over the caliph, continued to resist, and Nasir al-Dawla sent Ali against them. After scoring a victory over Abu'l-Husayn al-Baridi at al-Mada'in, Ali was named governor of Wasit and was awarded the laqab of Sayf al-Dawla ('Sword of the Dynasty'), by which he became famous.[8][18] This double award to the Hamdanid brothers marked the first time that a laqab incorporating the prestigious element al-Dawla was granted to anyone other than the vizier, the Caliphate's chief minister.[8]

The Hamdanids' success proved short-lived. They were politically isolated, and found little support among the Caliphate's most powerful vassals, the Samanids of Transoxiana and Muhammad ibn Tughj al-Ikshid of Egypt. Consequently, when in 943 a mutiny over pay issues broke out among their troops (mostly composed of Turks, Daylamites, Qarmatians and only a few Arabs), under the leadership of the Turk Tuzun, they were forced to quit Baghdad.[8][13][18] Caliph al-Muttaqi appointed Tuzun as amir al-umara, but soon quarrelled with him and fled north to seek Hamdanid protection. Tuzun defeated Nasir al-Dawla and Sayf al-Dawla in the field, and in 944 an agreement was concluded which allowed the Hamdanids to keep the Jazira and even gave them nominal authority over northern Syria (which at the time was not under Hamdanid control), in exchange for a large tribute. Henceforth, Nasir al-Dawla would be tributary to Baghdad, but his continued attempts to control Baghdad led to repeated clashes with the Buyids. In 958/9 Nasir al-Dawla would even be forced to seek refuge in the court of his brother, before Sayf al-Dawla could negotiate his return to Mosul with the Buyid emir Mu'izz al-Dawla.[13][19]

Establishment of the Emirate of Aleppo

Like other parts of the Abbasid empire, the collapse of Abbasid authority during the 'Anarchy at Samarra' led to a period of rival warlords competing for control of Syria. From 882, the region was ruled by the semi-autonomous Tulunid dynasty of Egypt, and direct Abbasid control was not restored until 903.[20] Soon after, the region became the focal point of a series of Qarmatian revolts, supported by the Bedouin of the Syrian Desert.[21][22] The Abbasids were able to retain a tenuous control over the province, until the authority of the Abbasid government collapsed in the civil wars of the 920s and 930s, where Nasir al-Dawla played a prominent role.[23]

Syria came under the control of another Egypt-based strongman, Muhammad ibn Tughj al-Ikhshid, in 935/6, but Ibn Ra'iq detached it from Egyptian control in 939/40. In 942, when Nasir al-Dawla replaced the assassinated Ibn Ra'iq, he attempted to impose his own rule over the region, and particularly Ibn Ra'iq's own province of Diyar Mudar. Hamdanid troops took control of the Balikh River valley, but the local magnates were still inclined towards al-Ikhshid, and Hamdanid authority was tenuous. Al-Ikhshid did not intervene directly, but supported Adl al-Bakjami, the governor of Rahba. Al-Bakjami captured Nasibin, where Sayf al-Dawla had left his treasures, but was finally defeated and captured by Sayf al-Dawla's cousin Abu Abdallah al-Husayn ibn Sa'id ibn Hamdan, and executed at Baghdad in May 943. Husayn then proceeded to occupy the entire province, from Diyar Mudar to the Thughur. Raqqa was taken by storm, but Aleppo surrendered without a fight in February 944.[8][24] Al-Muttaqi now sent messages to al-Ikhshid, asking for his support against the warlords who wanted to control him. The Hamdanids confined the caliph at Raqqa, but in summer 944 al-Ikhshid arrived in Syria. Husayn abandoned Aleppo to al-Ikhshid, who then visited the exiled caliph at Raqqa. Al-Muttaqi confirmed al-Ikhshid's control over Syria, but after the caliph refused to relocate himself to Egypt, the Egyptian ruler refused to commit himself to further aid for the caliph against his enemies. Al-Ikhshid returned to Egypt, and al-Muttaqi, powerless and dejected, went back to Baghdad, only to be blinded and deposed by Tuzun.[8][24][25]

It was in this context that Sayf al-Dawla turned his attention to Syria. The previous years had seen a series of personal humiliations, with defeats in the field by Tuzun followed by his failure to persuade al-Muttaqi to nominate him as amir al-umara. It was during the latter attempt that he also had one of his rivals, Muhammad ibn Inal al-Turjuman, assassinated. As Thierry Bianquis writes, following the failure of his brother's designs in Iraq, Sayf al-Dawla's turn to Syria was "born of resentment when, having returned to Nasibin, he found himself under-employed and badly paid".[8] Nasir al-Dawla seems to have encouraged his brother to turn to Syria after Husayn's failure there, writing to Sayf al-Dawla that "Syria lies before you, there is no one in this land who can prevent you from taking it".[26] With money and troops provided by his brother, Sayf al-Dawla invaded northern Syria in the wake of al-Ikhshid's departure.[24] He gained the support of the local Bedouin tribe of Banu Kilab, and even the Kilabi governor installed by al-Ikhshid in Aleppo, Abu'l-Fath Uthman ibn Sa'id al-Kilabi, who accompanied the Hamdanid in his unopposed entrance into the city on 29 October 944.[26][27][28]

Conflict with al-Ikhshid

Al-Ikhshid reacted, and sent an army north under Abu al-Misk Kafur to confront Sayf al-Dawla, who was then besieging Homs. In the ensuing battle, the Hamdanid scored a crushing victory. Homs then opened its gates, and Sayf al-Dawla set his sights on Damascus. Sayf al-Dawla briefly occupied the city in early 945, but was forced to abandon it in the face of the citizens' hostility.[26] In April 945 al-Ikhshid himself led an army into Syria, although at the same time he also offered terms to Sayf al-Dawla, proposing to accept Hamdanid control over northern Syria and the Thughur. Sayf al-Dawla rejected al-Ikhshid's proposals, but was defeated in battle in May/June and forced to retreat to Raqqa. The Egyptian army proceeded to raid the environs of Aleppo. Nevertheless, in October the two sides came to an agreement, broadly on the lines of al-Ikhshid's earlier proposal: the Egyptian ruler acknowledged Hamdanid control over northern Syria, and even consented to sending an annual tribute in exchange for Sayf al-Dawla's renunciation of all claims on Damascus. The pact was sealed by Sayf al-Dawla's marriage to a niece of al-Ikhshid, and Sayf al-Dawla's new domain received the—purely formal—sanction by the caliph, who also re-affirmed his laqab soon thereafter.[26][29][30]

The truce with al-Ikhshid lasted until the latter's death in July 946 at Damascus. Sayf al-Dawla immediately marched south, took Damascus, and then proceeded to Palestine. There he was confronted once again by Kafur, who defeated the Hamdanid prince in a battle fought in December near Ramla.[26][28] Sayf al-Dawla then retreated to Damascus, and from there to Homs. There he gathered his forces, including large Arab tribal contingents of the Uqayl, Kalb, Numayr, and Kilab, and in spring of 947, he attempted to recover Damascus. He was again defeated in battle, and in its aftermath the Ikhshidids even occupied Aleppo in July. Kafur, the de facto Ikhshidid leader after al-Ikhshid's death, did not press his advantage, but instead began negotiations.[26][31]

For the Ikhshidids, the maintenance of Aleppo was less important than southern Syria with Damascus, which was Egypt's eastern bulwark. As long as their control over this region was not threatened, the Egyptians were more than willing to allow the existence of a Hamdanid state in the north. Furthermore, the Ikhshidids realized that they would have difficulty in asserting and maintaining control over northern Syria and Cilicia, which were traditionally oriented more towards the Jazira and Iraq. Not only would Egypt, threatened by this time by the Fatimid Caliphate in the west, be spared the cost of maintaining a large army in these distant lands, but the Hamdanid emirate would also fulfill the useful role of a buffer state against incursions both from Iraq and from Byzantium.[26][29][32] The agreement of 945 was reiterated, with the difference that the Ikhshidids were no longer obligated to pay tribute for Damascus. The frontier thus established, between Jaziran-influenced northern Syria and the Egyptian-controlled southern part of the country, was to last until the Mamluks seized the entire country in 1260.[29][33]

Sayf al-Dawla, who returned to Aleppo in autumn, was now master of an extensive realm: the north Syrian provinces (Jund Hims, Jund Qinnasrin and the Jund al-Awasim) in a line running south of Homs to the coast near Tartus, and most of Diyar Bakr and Diyar Mudar in the western Jazira. He also exercised a—mostly nominal—suzerainty over the towns of the Byzantine frontier in Cilicia.[24][26][34] Sayf al-Dawla's domain was a "Syro-Mesopotamian state", in the expression of the Orientalist Marius Canard, and extensive enough to require two capitals: alongside Aleppo, which became Sayf al-Dawla's main residence, Mayyafariqin was selected as the capital for the Jaziran provinces. The latter were held ostensibly in charge of his elder brother Nasir al-Dawla, but in reality, the size and political importance of Sayf al-Dawla's emirate allowed him to effectively throw off the tutelage of Nasir al-Dawla. Although Sayf al-Dawla continued to show his elder brother due deference, henceforth, the balance of power between the two would be reversed.[24][26][23]

Arab tribal revolts

Aside from his confrontation with the Ikhshidids, Sayf al-Dawla's consolidation over his realm was challenged by the need to maintain good relations with the restive native Arab tribes.[35] Northern Syria at this time was controlled by Arab tribes, who had been resident in the area since the Umayyad period (661–750), and in many cases before that. The region around Homs was settled by the Kalb and the Tayy tribes, and the north, a broad strip of land from the Orontes to beyond the Euphrates, was controlled by the still largely nomadic Qaysi tribes of Uqayl, Numayr, Ka'b and Qushayr, as well as the aforementioned Kilab around Aleppo. Further south, the Tanukh were settled around Maarrat al-Nu'man, and the coasts were settled by the Bahra and Kurds.[36]

Sayf al-Dawla benefitted from the fact that he was an ethnic Arab, unlike most of the contemporary rulers in the Islamic Middle East, who were Turkic or Iranian warlords who had risen from the ranks of the military slaves (ghilman). This helped him win support among the Arab tribes, and the Bedouin played a prominent role in his administration.[37] On the other hand, in accordance with the usual late Abbasid practice familiar to Sayf al-Dawla and common across the Muslim states of the Middle East, the Hamdanid state was heavily reliant on and increasingly dominated by its non-Arab, mostly Turkic, ghilman. This is most evident in the composition of his army: alongside Arab tribal cavalry, which was often unreliable and driven more by plunder than loyalty or discipline, the Hamdanid armies made heavy use of Daylamites as heavy infantry, Turks as horse archers, and Kurds as light cavalry. These forces were complemented, especially against the Byzantines, by the garrisons of the Thughur, among whom were many volunteers (ghazi) from across the Muslim world.[37][38][39]

After winning recognition by the Ikhshidids, Sayf al-Dawla began a series of campaigns of consolidation. His main target was to establish firm control over the Syrian littoral, as well as the routes connecting it to the interior. The operations there included a difficult siege of the fortress of Barzuya in 947–948, which was held by a Kurdish brigand leader, who from there controlled the lower Orontes valley.[36] In central Syria, a Qarmatian-inspired revolt of the Kalb and Tayy erupted in late 949, led by a certain Ibn Hirrat al-Ramad. The rebels enjoyed initial success, even capturing the Hamdanid governor of Homs, but they were quickly crushed.[36] In the north, the attempts of the Hamdanid administrators to keep the Bedouin from interfering with the more settled Arab communities resulted in regular outbreaks of rebellion between 950 and 954, which had to be suppressed by Sayf al-Dawla's army.[36]

Finally, in spring 955 a major rebellion broke out in the region of Qinnasrin and Sabkhat al-Jabbul, which involved all tribes, both Bedouin and sedentary, including the Hamdanids' close allies, the Kilab. Sayf al-Dawla was able to resolve the situation quickly, initiating a ruthless campaign of swift repression that included driving the tribes into the desert to die or capitulate, coupled with diplomacy that played on the divisions among the tribesmen. Thus the Kilab were offered peace and a return to their favoured status, and were given more lands at the expense of the Kalb, who were driven from their abodes along with the Tayy, and fled south to settle in the plains north of Damascus and the Golan Heights, respectively. At the same time, the Numayr were also expelled and encouraged to resettle in the Jazira around Harran.[34][36] The revolt was suppressed in June, in what Bianquis calls "a desert policing operation perfectly planned and rigorously executed". It was only Sayf al-Dawla's "feelings of solidarity and his sense of Arab honour", according to Bianquis, that prevented the revolt from ending with the "total extermination, through warfare and thirst, of all the tribes".[36]

The suppression of the great tribal revolt marked, in the words of Kennedy, "the high point of Sayf al-Dawla’s success and power",[34] and secured the submission of the Bedouin tribes for the remainder of Sayf al-Dawla's reign.[36] In the same year, Sayf al-Dawla also aided the Kurdish warlord Daysam in capturing parts of Adharbayjan around Salmas. Daysam acknowledged Hamdanid suzerainty, but was evicted within a few months by the Sallarid emir Marzuban ibn Muhammad.[36][40]

Wars with the Byzantines

Through his assumption of control over the Syrian and Jaziran Thughur in 945/6, Sayf al-Dawla emerged as the chief Arab prince facing the Byzantine Empire, and warfare with the Byzantines became his main preoccupation.[24] Indeed, much of Sayf al-Dawla's reputation stems from his unceasing, though ultimately unsuccessful war with the Empire.[23][41]

By the early 10th century, the Byzantines had gained the upper hand over their eastern Muslim neighbours. The onset of decline in the Abbasid Caliphate after the Anarchy at Samarra was followed by the Battle of Lalakaon in 863, which had broken the power of the border emirate of Malatya and marked the beginning of the gradual Byzantine encroachment on the Arab borderlands. Although the emirate of Tarsus in Cilicia remained strong and Malatya continued to resist Byzantine attacks, over the next half-century the Byzantines overwhelmed the Paulician allies of Malatya and advanced to the Upper Euphrates, occupying the mountains north of the city.[42][43] Finally, after 927, peace on their Balkan frontier enabled the Byzantines, under John Kourkouas, to turn their forces east and begin a series of campaigns that culminated in the fall and annexation of Malatya in 934, an event which sent shock-waves among the Muslim world. Arsamosata followed in 940, and Qaliqala (Byzantine Theodosiopolis, modern Erzurum) in 949.[44][45][46]

The Byzantine advance evoked a great emotional response in the Muslim world, with volunteers, both soldiers and civilians, flocking to participate in the jihad against the Empire. Sayf al-Dawla was also affected by this atmosphere, and became deeply impregnated with the spirit of jihad.[36][37][47] The rise of the Hamdanid brothers to power in the frontier provinces and the Jazira is therefore to be regarded against the backdrop of the Byzantine threat, as well as the manifest inability of the Abbasid government to stem the Byzantine offensive.[48][49] In Kennedy's assessment, "compared with the inaction or indifference of other Muslim rulers, it is not surprising that Sayf al-Dawla's popular reputation remained high; he was the one man who attempted to defend the Faith, the essential hero of the time".[50]

Early campaigns

Sayf al-Dawla entered the fray against the Byzantines in 936, when he led an expedition to the aid of Samosata, at the time besieged by the Byzantines. A revolt in his rear forced him to abandon the campaign, and he only managed to send a few supplies to the town, which fell soon after.[51][52] In 938, he raided the region around Malatya and captured the Byzantine fort of Charpete. Some Arabic sources report a major victory over Kourkouas himself, but the Byzantine advance does not seem to have been affected.[51][52][53] His most important campaign in these early years was in 939–940, when he invaded southwestern Armenia and secured a pledge of allegiance and the surrender of a few fortresses from the local princes—the Muslim Kaysites of Manzikert and the Christian Bagratids of Taron and Gagik Artsruni of Vaspurakan—who had begun defecting to Byzantium, before turning west and raiding Byzantine territory up to Koloneia.[54][55][56] This expedition temporarily broke the Byzantine blockade around Qaliqala, but Sayf al-Dawla's preoccupation with his brother's wars in Iraq over the next years meant that the success was not followed up. According to the historian Mark Whittow, this was a major missed chance: a more sustained policy could have made use of the Armenian princes' distrust of Byzantine expansionism, to form a network of clients and contain the Byzantines. Instead, the latter were given a free hand, which allowed them to press on and capture Qaliqala, cementing their dominance over the region.[48][51][57]

Failures and victories, 945–955

After establishing himself at Aleppo in 944, Sayf al-Dawla resumed warfare against Byzantium in 945/6. From then until the time of his death, he was the Byzantines' chief antagonist in the East—by the end of his life Sayf al-Dawla was said to have fought against them in over forty battles.[58][59] Nevertheless, despite his frequent and destructive raids against the Byzantine frontier provinces and into Asia Minor, and his victories in the field, his strategy was essentially defensive, and he never seriously attempted to challenge Byzantine control of the crucial mountain passes or conclude alliances with other local rulers in an effort to roll back the Byzantine conquests. Compared to Byzantium, Sayf al-Dawla was the ruler of a minor principality, and could not match the means and numbers available to the resurgent Empire: the contemporary Arab sources report—with obvious, but nonetheless indicative, exaggeration—that Byzantine armies numbered up to 200,000, while Sayf al-Dawla's largest force numbered some 30,000.[51][59][60]

Hamdanid efforts against Byzantium were further crippled by the dependence on the Thughur system. The fortified militarized zone of the Thughur was very expensive to maintain, requiring constant provisions of cash and supplies from other parts of the Muslim world. Once the area came under Hamdanid control, the rump Caliphate lost any interest in providing these resources, and the scorched earth tactics of the Byzantines further reduced the area's ability to feed itself. Furthermore, the cities of the Thughur were fractious by nature, and their allegiance to Sayf al-Dawla was the result of his charismatic leadership and his military successes; once the Byzantines gained the upper hand and the Hamdanid's prestige declined, the cities tended to look out only for themselves.[61] Finally, Sayf al-Dawla's origin in the Jazira also affected his strategic outlook, and was probably responsible for his failure to construct a fleet, or to pay any attention at all to the Mediterranean, in stark contrast to most Syria-based polities in history.[34][51]

Sayf al-Dawla's raid of winter 945/6 was of limited scale, and was followed by a prisoner exchange.[51] Warfare on the frontiers then died down for a couple of years, and recommenced only in 948.[62] Despite scoring a victory over a Byzantine invasion in 948, he was unable to prevent the sack of Hadath, one of the main Muslim strongholds in the Euphrates Thughur, by Leo Phokas, one of the sons of the Byzantine Domestic of the Schools (commander-in-chief) Bardas Phokas.[51][62][63] Sayf al-Dawla's expeditions in the next two years were also failures. In 949 he raided into the theme of Lykandos but was driven back, and the Byzantines proceeded to sack Marash, defeat a Tarsian army and raid as far as Antioch. In the next year, Sayf al-Dawla led a large force into Byzantine territory, ravaging the themes of Lykandos and Charsianon, but on his return he was ambushed by Leo Phokas in a mountain pass. In what became known as the ghazwat al-musiba, the 'dreadful expedition', Sayf al-Dawla lost 8,000 men and barely escaped himself.[51][64]

Sayf al-Dawla nevertheless rejected offers of peace from the Byzantines, and launched another raid against Lykandos and Malatya, persisting until the onset of winter forced him to retire.[64] In the next year, he concentrated his attention on rebuilding the fortresses of Cilicia and northern Syria, including Marash and Hadath. Bardas Phokas launched an expedition to obstruct these works, but was defeated. Bardas launched another campaign in 953, but despite having a considerably larger force at his disposal, he was heavily defeated near Marash in a battle celebrated by Sayf al-Dawla's panegyrists. The Byzantine commander even lost his youngest son, Constantine, to Hamdanid captivity. Another expedition led by Bardas in the next year was also defeated, allowing Sayf al-Dawla to complete the re-fortification of Samosata and Hadath. The latter successfully withstood yet another Byzantine attack in 955.[51][65]

Byzantine ascendancy, 956–962

Sayf al-Dawla's victories brought about the replacement of Bardas by his eldest son, Nikephoros Phokas. Blessed with capable subordinates like his brother Leo and his nephew John Tzimiskes, Nikephoros would bring about a reversal of fortunes in Sayf al-Dawla's struggle with the Byzantines.[51][65] The new domestic of the schools also benefited from the culmination of military reforms that created a more professional army.[66]

In spring 956, Sayf al-Dawla pre-empted Tzimiskes from a planned assault on Amida, and invaded Byzantine territory first. Tzimiskes then seized a pass in Sayf al-Dawla's rear, and attacked him during his return. The hard-fought battle, fought amid torrential rain, resulted in a Muslim victory as Tzimiskes lost 4,000 men. At the same time, Leo Phokas invaded Syria and defeated and captured Sayf al-Dawla's cousin Abu'l-'Asha'ir, whom he had left behind in his stead. Later in the year, Sayf al-Dawla was obliged to go to Tarsus to help repel a raid by the Byzantine Cibyrrhaeot fleet.[51][65] In 957, Nikephoros took and razed Hadath, but Sayf al-Dawla was unable to react as he discovered a conspiracy by some of his officers to surrender him to the Byzantines in exchange for money. Sayf al-Dawla executed 180 of his ghilman and mutilated over 200 others in retaliation.[51][68] In the next spring, Tzimiskes invaded the Jazira, captured Dara, and scored a victory at Amida over an army of 10,000 led by one of Sayf al-Dawla's favourite lieutenants, the Circassian Nadja. Together with the parakoimomenos (chamberlain) Basil Lekapenos, he then stormed Samosata, and even inflicted a heavy defeat on a relief army under Sayf al-Dawla himself. The Byzantines exploited Hamdanid weakness, and in 959 Leo Phokas led a raid as far as Cyrrhus, sacking several forts on his way.[51][69]

In 960, Sayf al-Dawla tried to use the absence of Nikephoros Phokas with much of his army on his Cretan expedition, to re-establish his position. At the head of a large army, he invaded Byzantine territory and sacked the fortress of Charsianon. On his return, however, his army was attacked and almost annihilated in an ambush by Leo Phokas and his troops. Once again, Sayf al-Dawla managed to escape, but his military power was broken. The local governors now began to make terms with the Byzantines on their own, and the Hamdanid's authority was increasingly questioned even in his own capital.[60][70][71] Sayf al-Dawla now needed time, but as soon as Nikephoros Phokas returned victorious from Crete in summer 961, he began preparations for his next campaign in the east. The Byzantines launched their attack in the winter months, catching the Arabs off guard. They captured Anazarbus in Cilicia, and followed a deliberate policy of devastation and massacre to drive the Muslim population away. After Nikephoros repaired to Byzantine territory to celebrate Easter, Sayf al-Dawla entered Cilicia and claimed direct control over the province. He began to rebuild Anazarbus, but the work was left incomplete when Nikephoros recommenced his offensive in autumn, forcing Sayf al-Dawla to depart the region.[72][73] The Byzantines, with an army reportedly 70,000 strong, proceeded to take Marash, Sisium, Duluk and Manbij, thereby securing the western passes over the Anti-Taurus Mountains. Sayf al-Dawla sent his army north under Nadja to meet the Byzantines, but Nikephoros ignored them. Instead, the Byzantine general led his troops south and in mid-December, they suddenly appeared before Aleppo. After defeating an improvised army before the city walls, the Byzantines stormed the city and plundered it, except for the citadel, which continued to hold out. The Byzantines departed, taking with them some 10,000 inhabitants, mostly young men, as captives. Returning to his ruined and half-deserted capital, Sayf al-Dawla repopulated it with refugees from Qinnasrin.[72][74][75][76] The latter city was abandoned, resulting in a major blow to commerce in the region.[72]

Illness, rebellions and death

In 963, the Byzantines remained quiet as Nikephoros was scheming to ascend the imperial throne,[77] but Sayf al-Dawla suffered the loss of his sister, Khawla Sitt al-Nas, and was troubled by the onset of hemiplegia as well as worsening intestinal and urinary disorders, which henceforth confined him to a litter.[72] The disease limited Sayf al-Dawla's ability to intervene personally in the affairs of his state; he soon abandoned Aleppo to the charge of his chamberlain, Qarquya, and spent most of his final years in Mayyafariqin, leaving his senior ghilman to carry the burden of warfare against the Byzantines and the rebellions that sprang up in his domains. Sayf al-Dawla's physical decline, coupled with his military failures, especially the capture of Aleppo in 962, meant that his authority became increasingly shaky among his subordinates, for whom military success was the prerequisite for political legitimacy.[72][78]

Thus, in 961, the emir of Tarsus, Ibn az-Zayyat, unsuccessfully tried to turn over his province to the Abbasids. In 963, Sayf al-Dawla's nephew and governor of Harran, Hibat Allah, killed Sayf al-Dawla's trusted Christian secretary and rebelled in favour of his father, Nasir al-Dawla.[72] Nadja was sent to subdue the rebellion, forcing Hibat Allah to flee to his father's court, but then Nadja himself rebelled and attacked Mayyafariqin, defended by Sayf al-Dawla's wife, with the intention of turning it over to the Buyids. Nadja failed, and retreated to Armenia, where he managed to take over a few fortresses around Lake Van. In autumn 964 he again attempted to take Mayyafariqin, but was obliged to abandon it to subdue a revolt in his new Armenian domains. Sayf al-Dawla himself travelled to Armenia to meet his former lieutenant. Nadja re-submitted to his authority without resistance, but was murdered in winter 965 at Mayyafariqin, probably at the behest of Sayf al-Dawla's wife.[72] At the same time, Sayf al-Dawla pursued an alliance with the Qarmatians of Bahrayn, who were active in the Syrian Desert and opposed both to the Buyids of Iraq and to the Ikhshidids of Egypt.[72]

Despite his illness and the spreading famine in his domains, in 963 Sayf al-Dawla launched three raids into Asia Minor. One of them even reached as far as Iconium, but Tzimiskes, named Nikephoros' successor as Domestic of the East, responded by launching an invasion of Cilicia in winter. He destroyed an Arab army at the 'Field of Blood' near Adana, and unsuccessfully besieged Mopsuestia before lack of supplies forced him to return home. In autumn 964, Nikephoros, now emperor, again campaigned in the East, and met little resistance. Mopsuestia was besieged but held out, until a famine that plagued the province forced the Byzantines to withdraw.[72][79] Nikephoros returned in the next year and stormed the city and deported its inhabitants. On 16 August 965, Tarsus was surrendered by its inhabitants, who secured safe passage to Antioch. Cilicia became a Byzantine province, and Nikephoros proceeded to re-Christianize it by converting or expelling its Muslim population and inviting Christian settlers.[72][76][80]

The year 965 also saw two further large-scale rebellions within Sayf al-Dawla's domains. The first was led by a former governor of the coast, the ex-Qarmatian Marwan al-Uqayli, which grew to threatening dimensions: the rebels captured Homs, defeated an army sent against them and advanced up to Aleppo, but al-Uqayli was wounded in the battle for the city and died shortly after.[72][78] In autumn, a more serious revolt broke out in Antioch, led by the former governor of Tarsus, Rashiq ibn Abdallah al-Nasimi. The rebellion was obviously motivated by Sayf al-Dawla's inability to stop the Byzantine advance. After raising an army in the town, Rashiq led it to besiege Aleppo, which was defended by Sayf al-Dawla's ghilman, Qarquya and Bishara. Three months into the siege, the rebels had taken possession of part of the lower town, when Rashiq was killed. He was succeeded by a Daylamite named Dizbar. Dizbar defeated Qarquya and took Aleppo, but then departed the town to take control over the rest of northern Syria.[78][81] The rebellion is described in the Life of Patriarch Christopher of Antioch, an ally of Sayf al-Dawla. In the same year, Sayf al-Dawla was also heavily affected by the death of two of his sons, Abu'l-Maqarim and Abu'l-Baraqat.[72]

In early 966, Sayf al-Dawla asked for and received a short truce and an exchange of prisoners with the Byzantines, which was held at Samosata. He ransomed many Muslim captives at great cost, only to see them go over to Dizbar's forces. Sayf al-Dawla resolved to confront the rebel: carried on his litter, he returned to Aleppo, and on the next day defeated the rebel's army, helped by the defection of the Kilab from Dizbar's army. The surviving rebels were ruthlessly punished.[78][82] Sayf al-Dawla was still unable to confront Nikephoros when he resumed his advance. The Hamdanid ruler fled to the safety of the fortress of Shayzar while the Byzantines raided the Jazira, before turning on northern Syria, where they launched attacks on Manbij, Aleppo and even Antioch, whose newly appointed governor, Taki al-Din Muhammad ibn Musa, went over to them with the city's treasury.[76][82][83] In early February 967, Sayf al-Dawla returned to Aleppo, where he died on 8 February (24 Safar 356 AH), although a source claims that he died at Mayyafariqin. The sharif (a descendant of the Family of Muhammad) Abu Abdallah al-Aqsasi read the funeral prayers in Shi'a fashion. His body was embalmed and buried at a mausoleum in Mayyafariqin beside his mother and sister. A brick made of dust collected from his armour after his campaigns was reportedly placed under his head, according to his last will.[28][84][85] He was succeeded by his only surviving son (by his cousin Sakhinah), the fifteen-year-old Abu'l-Ma'ali Sharif, better known as Sa'd al-Dawla,[85][86] to whom Sayf al-Dawla ordered the oath of allegiance to be sworn before his death.[87][b] Sa'd al-Dawla's reign was marked by internal turmoil, and it was not until 977 that he was able to secure control of his own capital. By this time, the rump emirate was almost powerless. Transformed into a vassal state tributary to Byzantium by the 969 Treaty of Safar, it became a bone of contention between the Byzantines and the new power of the Middle East, the Fatimid Caliphate, that had recently conquered Egypt.[88][89]

Cultural activity and legacy

"Firm resolutions happen in proportion to the resolute,

and noble deeds come in proportion to the noble.

Small deeds are great in small men's eyes,

great deeds, in great men's eyes, are small.

Sayf al-Dawlah charges the army with the burden of his zeal,

which large hosts are not strong enough to bear,

And he demands of men what only he can do—

even lions do not claim as much."

Sayf al-Dawla surrounded himself with prominent intellectual figures, most notably the great poets al-Mutanabbi and Abu Firas, the preacher Ibn Nubata, the grammarian Ibn Jinni, and the noted philosopher al-Farabi.[91][92][c] Al-Mutanabbi's time at the court of Sayf al-Dawla was arguably the pinnacle of his career as poet.[93] During his nine years at Aleppo, al-Mutanabbi wrote 22 major panegyrics to Sayf al-Dawla,[94] which, according to the Arabist Margaret Larkin, "demonstrated a measure of real affection mixed with the conventional praise of premodern Arabic poetry."[93] The celebrated historian and poet, Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, was also part of the Hamdanid court, and dedicated his major encyclopedia of poetry and songs, Kitab al-Aghani, to Sayf al-Dawla.[95] Abu Firas was Sayf al-Dawla's cousin and had been raised at his court; Sayf al-Dawla had married his sister Sakhinah and appointed him governor of Manbij and Harran. Abu Firas accompanied Sayf al-Dawla on his wars against the Byzantines and was taken prisoner twice. It was during his second captivity from 962 to 966 that he wrote his famous Rūmiyyāt (i.e. Byzantine) poems.[96][97] Sayf al-Dawla's patronage of poets had a useful political dividend too: it was part of a court poet's duty to his patron to celebrate him in his work, and poetry helped spread the influence of Sayf al-Dawla and his court far across the Muslim world.[98] Sayf al-Dawla paid special favour to poets, but his court contained scholars versed in religious studies, history, philosophy and astronomy as well, so that, as S. Humphreys comments, "in his time Aleppo could certainly have held its own with any court in Renaissance Italy".[4][37] The Hamdanid emir himself probably also knew Greek, and was conversant with Ancient Greek culture.[28]

Sayf al-Dawla was also unusual for 10th-century Syria in his espousal of Twelver Shi'ism in a hitherto solidly Sunni country.[37] During his reign, the founder of the Alawite Shi'a sect, al-Khasibi, benefited from Sayf al-Dawla's patronage. Al-Khasibi turned Aleppo into the stable centre of his new sect, and sent preachers from there as far as Persia and Egypt with his teachings. His main theological work, Kitab al-Hidaya al-Kubra, was dedicated to his Hamdanid patron.[99] Sayf al-Dawla also erected a mausoleum to one of al-Husayn's sons, Muhassin, outside the city walls of Aleppo and close to a Christian monastery, called the Mashhad al-Dikka.[100][87] In the aftermath of the 962 sack of Aleppo, Sayf al-Dawla invited Alid sharifs from Qom and Harran to settle in his capital.[87] His active promotion of Shi'ism began a process whereby Syria came to host a large Shi'a population by the 12th century.[37]

Sayf al-Dawla played a crucial role in the history of the two cities he chose as his capitals, Aleppo and Mayyafariqin. His choice raised them from obscurity to the status of major urban centres; Sayf al-Dawla lavished attention on them, endowing them with new buildings, as well as taking care of their fortification. Aleppo especially benefited from Sayf al-Dawla's patronage: of special note is the great palace (destroyed in the Byzantine sack of 962) in the suburb of Halba outside Aleppo, as well as the gardens and aqueduct which he built there. Aleppo's rise to the chief city in northern Syria dates from his reign.[26][23]

Political legacy

Sayf al-Dawla has remained to modern times one of the best-known medieval Arab leaders. His bravery and leadership of the war against the Byzantines, despite the heavy odds against him, his literary activities and patronage of poets which lent his court an unmatched cultural brilliance, the calamities which struck him towards his end—defeat, illness and betrayal—have made him, in the words of Bianquis, "from his time until the present day", the personification of the "Arab chivalrous ideal in its most tragic aspect".[4][101][102]

Sayf al-Dawla's military record was, in the end, one of failure: he lost much of his territory to the Byzantines and, soon after his death, the rump emirate of Aleppo became a Byzantine vassal and an object of dispute with the Fatimids.[85][89] In retrospect, the Hamdanids' military defeat was inevitable, given the disparity of strength and resources with the Empire.[51] This weakness was compounded by the failure of Nasir al-Dawla to support his brother in his wars against Byzantium, by the Hamdanids' preoccupation with internal revolts, and the feebleness of their authority over much of their domains. As Whittow comments, Sayf al-Dawla's martial reputation often masks the reality that his power was "a paper tiger, short of money, short of soldiers and with little real base in the territories he controlled".[103] The defeat and expulsion of several Arab tribes in the great revolt of 955 also had unforeseen long-term consequences, as it left the Kilab as the dominant tribe in northern Syria. Associating themselves with the Hamdanids as auxiliaries, the Kilab managed to infiltrate the local cities, opening the path to their takeover of the emirate of Aleppo under the Mirdasid dynasty in the 11th century.[36]

Several distinguished officials served as his viziers, starting with Abu Ishaq Muhammad ibn Ibrahim al-Karariti, who had previously been in Abbasid employ. He was succeeded by Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Sulayman ibn Fahd, and finally by the celebrated Abu'l-Husayn Ali ibn al-Husayn al-Maghribi.[87] In the position of qadi of Aleppo, the Hamdanid emir dismissed the incumbent, Abu Tahir Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Mathil, and appointed Abu Husayn Ali ibn Abdallah al-Raqqi in his stead. When the latter was killed by the Byzantines in 960, Ibn Mathil was restored, and later succeeded by Abu Ja'far Ahmad ibn Ishaq al-Hanafi.[87] Though fiscal and military affairs were centralized in the two capitals of Aleppo and Mayyafariqin, local government was based on fortified settlements, which were entrusted by Sayf al-Dawla to relatives or close associates.[36]

The picture presented by his contemporaries on the impact of Sayf al-Dawla's policies on his own domains is not favourable. Despite the Hamdanids' origins among the Arab Bedouin, the Hamdanid emirate of Aleppo was a highly centralized state on the model of other contemporary Islamic polities, relying on a standing, salaried army of Turkic ghilman and Daylamite infantry which required enormous sums. This led to heavy taxation, as well as massive confiscation of private estates to sustain the Hamdanid military.[102][104] The 10th-century chronicler Ibn Hawqal, who travelled the Hamdanid domains, paints a dismal picture of economic oppression and exploitation of the common people, linked with the Hamdanid practice of expropriating extensive estates in the most fertile areas and practising a monoculture of cereals destined to feed the growing population of Baghdad. This was coupled with heavy taxation—Sayf al-Dawla and Nasir al-Dawla are said to have become the wealthiest princes in the Muslim world—which allowed them to maintain their lavish courts, but at a heavy price to their subjects' long-term prosperity.[87] According to Kennedy "even the capital of Aleppo seems to have been more prosperous under the following Mirdasid dynasty than under the Hamdanids",[102] and Bianquis suggests that Sayf al-Dawla's wars and economic policies both contributed to a permanent alteration in the landscape of the regions they ruled: "by destroying orchards and peri-urban market gardens, by enfeebling the once vibrant polyculture and by depopulating the sedentarised steppe terrain of the frontiers, the Hamdanids contributed to the erosion of the deforested land and to the seizure by semi-nomadic tribes of the agricultural lands of these regions in the 11th century".[87]

Notes

- ^ Full name and genealogy according to the Syrian historian Ibn Khallikan (d. 1282): ʿAlī ibn ʾAbū'l-Hayjāʾ ʿAbd Allāh ibn Ḥamdān ibn Ḥamdūn ibn al-Ḥārith ibn Lūqman ibn Rashīd ibn al-Mathnā ibn Rāfīʿ ibn al-Ḥārith ibn Ghatif ibn Miḥrāba ibn Ḥāritha ibn Mālik ibn ʿUbayd ibn ʿAdī ibn ʾUsāma ibn Mālik ibn Bakr ibn Ḥubayb ibn ʿAmr ibn Ghanm ibn Taghlib.[1]

- ^ Apart from Sa'd al-Dawla, only a daughter, Sitt al-Nas, survived her father.[87]

- ^ For a full list of the scholars associated with Sayf al-Dawla's court, cf. Bianquis 1997, p. 103 and Brockelmann, Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur, Vol. I, pp. 86ff., and Supplement, Vol. I, pp. 138ff.

References

- ^ Ibn Khallikan 1842, p. 404.

- ^ a b c d e Canard 1971, p. 126.

- ^ Özaydin 2009, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d Bianquis 1997, p. 103.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Bonner 2010, pp. 313–327.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 265–266, 269.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bianquis 1997, p. 104.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 266, 268.

- ^ Canard 1971, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 267–268.

- ^ a b c Canard 1971, p. 127.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 268.

- ^ Bianquis 1997, pp. 104, 107.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 192–195.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 195–196.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 270.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Humphreys 2010, pp. 535–536.

- ^ Humphreys 2010, pp. 536–537.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 286–287.

- ^ a b c d Humphreys 2010, p. 537.

- ^ a b c d e f Canard 1971, p. 129.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 196, 312.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bianquis 1997, p. 105.

- ^ Bianquis 1993, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d Özaydin 2009, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 273.

- ^ Bianquis 1998, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Bianquis 1998, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Bianquis 1998, pp. 114, 115.

- ^ Bianquis 1997, pp. 105, 107.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy 2004, p. 274.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 273–274.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bianquis 1997, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d e f Humphreys 2010, p. 538.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 269, 274–275.

- ^ McGeer 2008, pp. 229–242.

- ^ Madelung 1975, pp. 234–235.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 275.

- ^ Toynbee 1973, pp. 110–111, 113–114, 378–380.

- ^ Whittow 1996, pp. 310–316, 329.

- ^ Toynbee 1973, pp. 121, 380–381.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 479–484.

- ^ Whittow 1996, pp. 317–322.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 277–278.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 276.

- ^ Whittow 1996, p. 318.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 278.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bianquis 1997, p. 107.

- ^ a b Treadgold 1997, p. 483.

- ^ Whittow 1996, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Ter-Ghewondyan 1976, pp. 84–87.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 483–484.

- ^ Whittow 1996, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Whittow 1996, pp. 320, 322.

- ^ Bianquis 1997, pp. 106–107.

- ^ a b Whittow 1996, p. 320.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 277.

- ^ McGeer 2008, pp. 244–246.

- ^ a b Whittow 1996, p. 322.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 488–489.

- ^ a b Treadgold 1997, p. 489.

- ^ a b c Treadgold 1997, p. 492.

- ^ On the nature of these reforms, cf. Whittow 1996, pp. 323–325

- ^ The description of this ceremony survives in De Ceremoniis, 2.19. McCormick 1990, pp. 159–163

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 492–493.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 493.

- ^ Bianquis 1997, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 495.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bianquis 1997, p. 108.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 495–496.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 277, 279.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 496–497.

- ^ a b c Whittow 1996, p. 326.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 498–499.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy 2004, p. 279.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 499.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 500–501.

- ^ Bianquis 1997, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b Bianquis 1997, pp. 108, 109.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 501–502.

- ^ Bianquis 1997, pp. 103, 108, 109.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 280.

- ^ El Tayib 1990, p. 326.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bianquis 1997, p. 109.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 280–282.

- ^ a b Whittow 1996, pp. 326–327.

- ^ van Gelder 2013, p. 61.

- ^ Humphreys 2010, pp. 537–538.

- ^ Kraemer 1992, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b Larkin 2006, p. 542.

- ^ Hamori 1992, p. vii.

- ^ Ahmad 2003, p. 179.

- ^ Kraemer 1992, p. 90.

- ^ El Tayib 1990, pp. 315–318, 326.

- ^ Bianquis 1997, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Moosa 1987, p. 264.

- ^ Amabe 2016, p. 64.

- ^ Humphreys 2010, pp. 537–539.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 265.

- ^ Whittow 1996, p. 334.

- ^ Amabe 2016, p. 57.

Bibliography

- Ahmad, Zaid (2003). The Epistemology of Ibn Khaldūn. London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0-203-63389-2.

- Amabe, Fukuzo (2016). Urban Autonomy in Medieval Islam: Damascus, Aleppo, Cordoba, Toledo, Valencia and Tunis. Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-31026-1.

- Bianquis, Thierry (1993). "Mirdās, Banū or Mirdāsids". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 115–122. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Bianquis, Thierry (1997). "Sayf al-Dawla". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 103–110. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Bianquis, Thierry (1998). "Autonomous Egypt from Ibn Ṭūlūn to Kāfūr, 868–969". In Petry, Carl F. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume 1: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 86–119. ISBN 0-521-47137-0.

- Bonner, Michael (2010). "The Waning of Empire, 861–945". In Robinson, Chase F. (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 305–359. ISBN 978-0-521-83823-8.

- Canard, Marius (1971). "Ḥamdānids". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 126–131. OCLC 495469525.

- El Tayib, Abdullah (1990). "Abū Firās al-Ḥamdānī". In Ashtiany, Julia; Johnstone, T. M.; Latham, J. D.; Serjeant, R. B.; Smith, G. Rex (eds.). ʿAbbasid Belles-Lettres. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 315–327. ISBN 978-0-521-24016-1.

- Hamori, Andras (1992). The Composition of Mutanabbī's Panegyrics to Sayf Al-Dawla. Leiden and New York: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09366-9.

- Humphreys, Stephen (2010). "Syria". In Robinson, Chase F. (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 506–540. ISBN 978-0-521-83823-8.

- Ibn Khallikan (1842). Ibn Khallikan's Biographical Dictionary, Translated from the Arabic. Vol. I. Translated by Baron Mac Guckin de Slane. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. OCLC 1184199260.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Kraemer, Joel L. (1992). Humanism in the Renaissance of Islam: The Cultural Revival During the Buyid Age (2nd Revised ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09736-0.

- Larkin, Margaret (2006). "Al-Mutanabbi, Abu'l-Tayyib Ahmad ibn al-Husayn al-Ju'fi". In Meri, Josef W. (ed.). Medieval Islamic civilization, an Encyclopedia. Vol. 1, A–K, Index. New York: Routledge. pp. 542–543. ISBN 978-0-415-96691-7.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1975). "Minor dynasties of northern Iran". In Frye, Richard N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 198–250. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- McCormick, Michael (1990). Eternal Victory: Triumphal Rulership in Late Antiquity, Byzantium and the Early Medieval West. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38659-3.

- McGeer, Eric (2008). Sowing the Dragon's Teeth: Byzantine Warfare in the Tenth Century. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Studies. ISBN 978-0-88402-224-4.

- Moosa, Matti (1987). Extremist Shiites: The Ghulat Sects. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2411-0.

- Özaydin, Abdülkerim (2009). "Seyfüddevle el-Hamdânî". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 37 (Sevr Antlaşmasi – Suveylîh) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-975-389-589-7.

- Ter-Ghewondyan, Aram (1976) [1965]. The Arab Emirates in Bagratid Armenia. Translated by Garsoïan, Nina. Lisbon: Livraria Bertrand. OCLC 490638192.

- Toynbee, Arnold (1973). Constantine Porphyrogenitus and His World. London and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-215253-4.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- van Gelder, G. J. H. (2013). Classical Arabic Literature: A Library of Arabic Literature Anthology. New York and London: NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-3826-9.

- Whittow, Mark (1996). The Making of Byzantium, 600–1025. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20496-6.

Further reading

- Ayyıldız, Esat (2020). "El-Mutenebbî'nin Seyfüddevle'ye Methiyeleri (Seyfiyyât)" [Al-Mutanabbī’s Panegyrics to Sayf al-Dawla (Sayfiyyāt)]. BEÜ İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi (in Turkish). 7 (2): 497–518. doi:10.33460/beuifd.810283. S2CID 228935099.

- Canard, Marius (1934). Sayf al-Daula. Recueil de textes relatifs à l'émir Sayf al-Daula le Hamdanide, avec annotations, édité par M. Canard (in French). Algiers: J. Carbonel. OCLC 247435034.

- Canard, Marius (1948). "Les H'amdanides et l'Arménie". Annales de l'Institut d'Études Orientales (in French). VII: 77–94. OCLC 715397763. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Canard, Marius (1951). Histoire de la dynastie des Hamdanides de Jazîra et de Syrie (in French). Algiers: Faculté des Lettres d'Alger. OCLC 715397763.

- Garrood, William (2008). "The Byzantine Conquest of Cilicia and the Hamdanids of Aleppo, 959–965". Anatolian Studies. 58: 127–140. doi:10.1017/s006615460000870x. ISSN 0066-1546. JSTOR 20455416. S2CID 162596738.

External links

- "al-Mutanabbi to Sayf al-Dawla". Princeton Online Arabic Poetry Project. Retrieved 17 July 2012.