San Pedro Cholula

San Pedro Cholula | |

|---|---|

Location of the municipality in Puebla | |

| Coordinates: 19°03′48″N 98°18′23″W / 19.06333°N 98.30639°W | |

| Country | |

| State | Puebla |

| Founded | 500-200 BCE |

| Municipal Status | 1861 |

| Seat | Cholula |

| Government | |

| • Municipal President | Francisco Andres Cobarrubias Pérez |

| Area | |

• Municipality | 51.03 km2 (19.70 sq mi) |

| Elevation (of seat) | 2,190 m (7,190 ft) |

| Population (2005) Municipality | |

• Municipality | 113,436 |

| • Urban area | 82,964 |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (US Central)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (Central) |

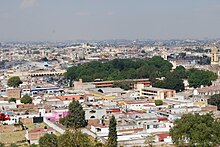

San Pedro Cholula is a municipality in the Mexican state of Puebla and one of two municipalities which made up the city of Cholula. The city has been divided into two sections since the pre Hispanic era, when revolting Toltec-Chichimecas pushed the formerly dominant Olmec-Xicallanca to the eastern side of the city in the 13th century. The new lords called themselves Cholutecas and built a new temple to Quetzalcoatl on the San Pedro side, which eventually eclipsed the formerly prominent Great Pyramid of Cholula, now on the San Andrés side. When the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, the city of Cholula was an important religious and economic center, but the center of power was on the San Pedro side, centered on what is now the main city plaza and the San Gabriel monastery. The division of the city persisted and San Pedro remained the more dominant, with Spanish families moving onto that side and the rest of the population quickly becoming mestizo. Today, San Pedro is still more commercial and less residential than neighboring San Andrés with most of its population employed in industry, commerce and services rather than agriculture. Although Cholula's main tourist attraction, the Pyramid, is in San Andrés, San Pedro has more tourism infrastructure such as hotels, restaurants and bars.

San Pedro as part of the city of Cholula

San Pedro is one of two municipalities which make up the city of Cholula, or formally Cholula de Rivadavia. This city is divided into eighteen barrios or neighborhoods, ten of which are on the San Pedro side.[1] The division of the city into two semi-separate halves has its roots in the pre Hispanic period, when the Olmec-Xicallancas were pushed to the east side of the city by the rebelling Toltec-Chichimeca ethnicity. The division remained in the colonial period with San Pedro quickly becoming a mix of Spanish and indigenous with San Andrés remaining mostly indigenous for the rest of the period.[2] Today, San Andrés still has the higher indigenous population.[3]

When the Spanish arrived the San Pedro side was still dominant, with the Quetzalcoatl Temple (on which now stands the San Gabriel monastery) overshadowing the Great Pyramid of Cholula, which was already overgrown. This side contains what is considered the center of the city, large plaza with several important buildings, including the San Gabriel monastery, facing it.[4]

What keeps the city united socially is a complex calendar of religious and social events with the costs and efforts associated with them rotated and shared among the various "barrios" or traditional neighborhoods.[1] Among the important shared festivals, there are Carnival,[5] the Vaniloquio, when the bells of the city's churches ring in coordination,[6] Holy Week, La Bajada, when the image of the Virgin of the Remedies comes down the pyramid to visit the various neighborhoods and the most important, the feast day of the Virgin of the Remedies on 8 September.[7]

These and other traditions have roots in the pre Hispanic period. Many Cholutecans still use their pre-Hispanic surnames, such as former town stewards Raymundo Tecanhuehue and Humberto Tolama Totozintle. This is because a number of the old Indian nobility was allowed certain privileges after the Conquest.[3] The town chronicler still refers to the barrios as calpulli, the pre-Conquest political organization of neighborhoods.[3]

Another unifying factor is a straight street grid oriented in the cardinal directions. Most streets in the center are numbered with indications as to their location vis-à-vis the center, north, east, south or west. Outside the city center street names lose this system.[8]

Landmarks

San Pedro is home to what is considered to be the main plaza or square the city, called the Plaza de la Concordia. In the morning, this plaza of Cholula is filled with vendors selling typical street food, sweets and handcrafted toys for children.[9] On the west side of this plaza is the "Portales" (Portals). This is a commercial area framed by forty-six arches supported by Doric columns.[10] These arches measure 170 meters long and are the longest in Latin American. (pedro his).[10] The San Pedro municipal palace is located behind this commercial area, occupying a space which was called the Xiuhcalli, (House of Turquoise), where a council of nobles met in the pre Hispanic era.[11]

On the south side of the plaza is the Museum of the City of Cholula, housed in a structure called the Casa del Caballero Aguilar (House of the Eagle Knight), one of the oldest residential structures in the area. This museum was opened in 2001 after extensive restoration of the colonial era building by INAH, the city and the Universidad de las Américas-Puebla. This work restored the original floor plan and much of the carved stone work. The museum traces the habitation of Cholula from about 1000 BCE. Three rooms display pre Hispanic artifacts, two contains colonial era items and one features a John O'Leary photographic exhibit of the city's religious festivals. Lastly, the facility also contains restorations laboratories run by UDLAP. The basis of the collection was a group of 1,500 artifacts donated by Omar Jimenez.[8][12]

The main archeological attraction, the Great Pyramid of Cholula is actually in the municipality of San Andrés Cholula, marking where that part of the city begins. However, 154 hectares of the entire city have been declared archeological heritage. It is strongly believed that the Quetzalcoatl Temple lies beneath the San Gabriel monastery, but no excavations have been done on the site.[3][10] Most excavations in San Pedro have been under streets and other public areas, especially when there has been construction, such as the laying of water pipes. However, there is widespread opposition to excavation in most of the zone, mostly because most of the land is privately owned.[13]

More evident in San Pedro is a large number of Cholula's many churches. According to legend, Hernán Cortés promised to build one church here for every day of the year or for every pre Hispanic temple destroyed after the Cholula Massacre.[14] In reality, there are only 37 for the entire city, 159, if all the chapels on surrounded haciendas and ranches are counted.[9] The architectural styles of the churches vary from Gothic to Renaissance to Churrigueresque and Neoclassical, with many mixing elements of two or more styles. A number also have Talavera tile as a decorative feature, which is common in Puebla. A few have intricate stucco work done by indigenous hands.[9] The city's churches contain more than 300 works of art, together valued at millions of dollars. However, due to increases in the theft of religious art, many churches have implemented extra security measures and some have stopped opening during the week.[15][16]

The most important religious institution in San Pedro, and the second most important after the Sanctuary of the Virgen de los Remedios on the Great Pyramid, is the San Gabriel monastery. This monastery was established over the site of the destroyed Quetzalcoatl Temple in 1529 and one of the largest Franciscan friaries in Mexico.[4] It was established first in the city, because this was the power center and the Franciscans had a limited number of monks in Mexico.[2] The complex consists of a large atrium, a main church, a cloister area, and two important chapels which face the atrium area. Its architecture is rococo style Gothic.[4]

The Franciscan friary is dedicated to the Archangel Gabriel. The complex is surrounded by a wall with pointed merlons which separates it from the main plaza of the city. There are three entrances to the atrium, but the main one is to the west, in front of the main church. The atrium is very large and most of it is in front of the two chapels. A second entrance in the atrium wall leads to this area, which may have been used for evangelization purposes and masses for the indigenous during the very early colonial period. In three corners of the atrium, there are chapels, called "capillas posas", with pinnacle roofs, simple arches which are closed off by railing.[17] The atrium cross was sculpted in 1668. It is identical to that in the atrium of the Nuestra Señora de los Remedios sanctuary.[17] The main church is one of the oldest in Mexico, which the first stone laid in 1549 by Martin de Hojacastro, who would be the third bishop of Puebla.[17] The facade of the main church is smooth and its corners are reinforced with diagonal buttresses. The towers have arched windows, columns and a small dome topped by iron cross. The interior has a Latin cross layout, covered with vaults and a cupola. The altarpieces are made of wood and plaster and decorated in gold leaf. The main one is dedicated to the Virgin of the Remedies. The main portal is sculpted in sandstone in Renaissance style. The main doors are of wood and contain metal studs with different designs. The north portal has richer ornamentation. The interior is covered by vaults with Gothic nerves and arched window openings. It conserves a number of oil paintings from the 17th and 18th centuries. The main altar of San Gabriel is Neoclassical, dating from 1897.[18]

The cloister contains frescos with six religious scenes in a style similar to those at the former monastery of Huejotzingo. The upper floor has one called the Mass of Saint Gregory and the ground floor contains frescos with scenes from the life of Francis of Assisi, along with portraits of a number of Franciscan friars.[4][17] The San Gabriel monastery is still inhabited by about fifteen Franciscan friars. In 1986, the monastery agreed to let part of their building be renovated and converted into the Franciscan Library, done in cooperation with the Universidad de las Americas. This library is open to the public on request. The monks were initially opposed to the project as they know the monastery sits on the Temple of Quetzalcoatl and did not want to be forced out.[3]

The Capilla Real (Royal Chapel) is also called the Capilla de Naturales (Indigenous Chapel). It is located on the north end of the complex. It is similar to a mosque. It had never received any kind of royal recognition. There are twelve columns and twenty-four octagonal pilasters. Twelve of the pilasters support the entrances to the side chapels and have sixteen corbels. There are seven naves and forty-nine cupolas.[17] The capilla real received its name because of a chapel inside dedicated to the Virgin of the Remedies, the patron of Cholula. The current interior was created in 1947. The façade has some Baroque elements, with its main entrance marked by a simple arch flanked by Corinthian columns and fluted pilasters. The choral window is flanked by Ionic columns. The crest is a pediment with a flutter.[4] The holy water font dates from the 16th century. The base and cup are sculpted from one piece of stone. The base is decorated with acanthus leaves, other flowers and leaves and a simple molding a Franciscan cord.[17]

The Capilla de la Tercera Orden is located between the Capilla Real and the main church. It is a small church with a Baroque portal and Salomonic columns. In the pendentives of the cupola, there are paintings of various important Franciscans. The altars are Neoclassical in white and gold.[17]

The parish church of the San Pedro municipality faces that main square of the city and was built in the 17th century.[10][18] The architecture is a mix of Baroque and Renaissance, which is uncommon in Mexico for the 17th century. The bell tower is Baroque and one of the tallest in the city. It has a Latin cross layout and a vaulted ceiling. The interior has been restored and contain a Churrigueresque cupola, along with 18th-century paintings such as depictions of Christ by Diego de Borgraf.[8][17]

The various barrios or traditional urban neighborhoods and communities of the municipality have their own parish church dedicated to a patron saint, and some have more than this. The oldest of these churches dates from the 16th century and a number are painted in what is called "popular Baroque" with bright colors.[1]

The San Miguel Tianguishahuatl church is located behind the San Gabriel monastery and is dedicated to the Archangel Michael. Its atrium is entered through arches that separate it from the street. This church was built in the 19th century with one nave and covered in cannon vaults and a cupola over the presbytery. The main portal of the church is a simple arch supported by pilasters. There are two other arches which lead to small chapels. Above the facade, there is a single bell tower. The interior contains Neoclassical altars with ornamentation typical of the 19th century.[17]

The Jesus Tlatempa church is distinguished by its tall bell tower, the tallest in Cholula and dedicated to Jesus the Nazarene. It was built in the 17th century. It has a sober portal with a simple arch and pilasters. Above it, there is a choral window decorated with pinnacles and small spheres. Above this, there is a Calatrava coat of arms, topped by an anagram. The bell tower has a wide base and three levels. The first and second have highly decorated windows and a balcony, and the third has a simpler octagon window. The interior has two vaults. In the upper choir, there are pelicans serving as an allegory of Christ.[17]

The Santiago Mixquitla church is located in the far northwest of the city. The complex in entered through a portal with three arches, an entablature and pinnacles. This leads into a very large atrium, which is surrounded by a stone wall similar to that of the San Gabriel monastery. The facade of the church is wide and has a portal of grey sandstone, sculpted in a sober style from the 17th century. The entrance is formed by an arch supported by two pilasters. Above this, there is a choral window with two pilasters and two coats of arms. One belongs to Mexico and the other to Cholula. Above this, there is a niche which contains a cross. On either side, there are two pyramids with spheres. The bell tower has Salomonic columns on its corners. The church has three naves, with an octagonal cupola, some paintings and altarpieces. There is a sculpture of Saint James on horseback in the main altar area.[17]

The San Matias Cocoyotla church is one of the oldest parish churches in the region, dating from the 17th century. It has a Renaissance style portal with Herrerian style crests. The interior is covered by three vaults, which are decorated with gilded plasterwork.[17]

The San Juan Texpolco church dates from the 17th century and is dedicated to John the Evangelist as he was crucified. The church is oriented east–west. It has one bell tower and its facade is in the shape of a niche. Inside, it has three short naves, and an octagonal cupola.[17]

The San Cristobal Tepontla church is the farthest from the city center. The facade is bordered by plants sculpted in stone. It has a small bell tower, with one level square and the other as an octagon.[17]

The Santa Maria Xixitla church is in the southwest of the city. The entrance to the atrium has three arches. The exterior of the church looks somewhat like a castle with buttresses and pinnacles, and a simple facade. The bell tower has Salomonic and estipite columns. The atrium has a cross sculpted with signs of the Passion, dating from the 16th century, the only one from that time period in Cholula. The interior has three naves covered in vaults and an octagonal cupola.[17]

The La Magdalena Coapa church has a Neoclassical facade. Its interior is covered by three vaults and a circular cupola. The cypress in the presbytery has been there since the beginning of the 20th century.[17]

The San Pedro Mexicaltzingo church has a very simple facade with a round arch doorway, imposts and narrow jambs on its also narrow windows. It was probably built in the 19th century but conserves its 16th-century holy water font.[17]

The San Pablo Tecama church is the unification of two church buildings, one from the 17th century, converted into the sacristy and the other from the 19th century. The older church building has a bell tower with pilasters and Salomonic columns on two levels, with an open cone (oculo) as a crest. The 19th-century building contains various Neoclassical altarpieces along with paintings. It also has a bell tower. The complex makes it one of the largest churches in Cholula.[17]

The Santa Cruz de Jerusalén church is done in a style called barroco republican (Republican Baroque) or neoclasico abarrocado (Baroque Neoclassical), which was popular in Mexico in the 19th century. It has a portal with a simple arch, which is highly decorated supported by Doric columns. Above this, there is a coat of arms of the Holy Burial in Jerusalem and a niche containing an image of Francis of Assisi. On either side, there are large flowerpots covered in Talavera tile. There are two towers which contain sections that are square and cylindrical. The corners are decorated with volutes, small domes and "linternillas" to let in light. The interior is white with gold accents, with a number of paintings.[17]

The Santo Sepulcro church is located in the far northwest of the city. The facade is simple with a round arch for the entrance. This portal has two crests in the shape of pyramids with sphere which date from the 17th century. Above this, there is a choral window flanked by small pilasters with pinnacles. The bell tower was never completed and its brickwork can still be seen. The interior has a Latin cross layout, with a short principal nave and a cupola. There are a number of paintings along with altarpieces.[17]

The San Miguelito church is located in the north of the city. It is small, but the arch that leads into the atrium is considered to be significant. It is a semicircular arch flanked by estipite (inverted truncated pyramids) pilasters and there is a niche with estipites and topped by a cross. The facade of the church is brick. The bell tower is low with only a part of it decorated with estipite pilasters. The interior has one cannon vault and a cupola. There are a number of paintings inside, some are folk artwork and some are by masters. One of the latter is the Virgin de la luz by Luis Berrueco from the 17th century.[17]

This side of the city contains a number of large markets as it is more commercial and less residential than the San Andrés side.[8] The Mercado Municipal has managed to conserve the look of traditional Mexican markets, with women seated on the floor selling seeds, flowers, herbs, and more. There is a cold chocolate and water, whipped until foamy served in wooden bowls with flowers painted on them.[19] "Ponche" in Cholula is a drink prepared with blue corn and milk.[4] This market is augmented on Wednesday and Sundays by a tianguis, when people from surrounding communities come to buy and sell. The market specializes in locally produced products, especially flowers, fruit and vegetables. There are also food stands preparing local dishes.[10] The Cosme del Razo market on Calles 3 and 5 Norte has food stands which serve local specialties.[8] The Centro Artesanal Xelhua display s wide variety of handcrafts made in the area.[18]

La Quinta Luna was selected to be a member of the Hoteles Boutique de México. It was built as a house in the 17th century and it is catalogued as a historic monument by INAH. It has a courtyard in the center, containing a garden. It is located in the Santa María Xixitla neighborhood. It was the home of an indigenous noble by the name of Juan de León y Mendoza. The hotel contains seven luxury rooms, a meeting room, a library, a lobby and a restaurant. The library area contains about 3,000 books and its roof is crossed by beams which were rescued during renovations to the building. The lobby and restaurant are located in what was the chapel. The decoration is based in paintings by Federico Silva and Gerardo Gomez Brito, various pieces done in local onyx and a number of antiques from various places in the world. The lobby occasionally hosts small concerts. It has adobe walls and very high ceilings.[20]

Education

The municipality has forty preschools, forty-three primary schools, twenty-one middle schools and thirteen high schools. There are six technical/professional schools above this level as well as an extension of the Universidad de las Américas.[4]

History

The first human settlements of Cholula are on the San Andrés side of the city, dating somewhere between 500 and 200 BCE, during the middle Preclassic period.[20][21] Through the Classic period, the village grew and social hierarchy developed, with the first pyramid to define this social and religious hierarchy begun at the end of the Preclassic.[21]

At the end of this period, many settlements were abandoned, but Cholula grew, making it politically dominant in the region. It rapidly developed into an urban center in the Classic period (200-800 CE) dominating the Puebla-Tlaxcala region, growing to an area of about four km2 and a population of between 20,000 and 25,000. The Great Pyramid was expanded twice during this time. The city had relations with the larger Teotihuacan, but the nature of this is not known. However, at the end of the Classic period, Teotihuacan fell. Cholula had a population decline, but the city survived.[21] However, there is evidence of a change of dominant ethnicity, with a people known as the Olmec-Xicallana coming to power and pottery and other artifacts showing Gulf Coast influence.[21] The city continued to grow during the Post Classic period (900–1521) as well, although there was another regime change. Toltec-Chichimecas from the fall the Tula arrived in the 12th century as refugees. The ruling Olmeca-Xicallanca allowed their arrival but oppressed them, until the Toltec-Chichimecas revolted and took over in the 13th century. The new lords called themselves the Choloteca, but they did not eliminate the Olmeca-Xicallanca. The defeated group was pushed to the eastern half of the city with the new rulers living on the San Pedro side and constructing a new religious center, the Quetzalcoatl Temple to replace the Pyramid.[21] This is the origin of the division of the city.[2]

By the time the Spanish arrived, Cholula was actually divided into three sub entities, roughly corresponding to the municipalities of San Pedro Cholula, San Andrés Cholula and Santa Isabel Cholula. However, only the first two are considered to be part of the modern city of Cholula.[22] San Pedro is defined by the main plaza of the city west of the Great Pyramid and area west of that.[22] The city was important as a mercantile crossroads and a religious center, although religious practice was centered on the Quetzalcoatl Temple in San Pedro rather than on the Pyramid, which was overgrown.[4][14][21][23] Hernán Cortés noted he could see about 2,000 houses in the city with as many temples as days of the year.[4] It had a population of about 100,000;[14] however, the area was overpopulated leading to chronic hunger among the poor.[21] During the Conquest, the Spanish would kill about 6,000 residents of the city in an event known as the Cholula Massacre. It is from this episode that the 365 churches legend evolves.[8][21][24] The two parts of town were divided into encomiendas for a very short time, but in 1537 the entirety would be declared a city by the Spanish Crown, receiving its coat of arms in 1540.[4] However, there is evidence that the division of the city was recognized since the early colonial period. The Franciscans established themselves in San Pedro first, with the San Gabriel monastery because this was the power center of the city and at first the monks were not sufficient to be spread out around the entire city. This early emphasis on the San Pedro side, along with the settling of the Spanish population almost exclusively here, resulted in this side of the city becoming mixed race (mestizo) early in the colonial era. Evidence of political distinctions can be found as early as 1548, but in 1714, the two halves were definitely separated when San Andrés was made an Indian Republic. This separation would cause political and economic problems between the two halves of the city, but still coexisting in matters of religion.[2] The two municipalities were established by 1861.[22] However, the two halves never completely split and the two municipalities formed a partial union called the Distrito Cholula de Rivadavia in 1895, with the appendage in honor of Bernardino de Rivadavia.[4] As such, San Pedro is part of what is the oldest continuously inhabited city in the Americas.[8]

Neighborhoods and festivals

Ten of Cholula's eighteen barrios or traditional urban neighborhoods are located in San Pedro. These barrios have their roots in the pre Hispanic period, but after the Conquest, the Spanish reorganized them around parish churches giving each a patron saint.[1] The neighborhoods of San Pedro Cholula are San Miguel Tianguisnahuac, Jesús Tlatempa, Santiago Mixquitla, San Matias Cocoyotla, San Juan Calvario Texpolco, San Cristóbal Tepontla, Santa María Xixitla, La Magdalena Coapa, San Pedro Mexicaltzingo and San Pablo Tecama.[1] Almost all of the oldest and most central neighborhoods of the city are in San Pedro and include, Tianguisnahuac, Calvario, Tlatempa, Mexicaltzingo, Xixitla and Tecama.[7]

The main unifying factor of the city is its complicated system of mostly religious festivals which occur year-round. This has been true of Cholula since the pre Hispanic period, although religious rituals have changed.[1] The most important of these festivals are celebrated citywide. These include Vaniloquio (when church bells are rung in concert), Holy Week, Carnival, and Fiesta del Pueblo with the two most important being the Bajada, which the Virgin of the Remedies leaves her sanctuary on the Pyramid to visit the various barrios and the feast for this same Virgin image on 8 September.[10] For these and more local festivals, the costs and efforts associated with them are shared in a complicated system of "mayordomos" who sponsor a particular event in a particular year. Mayordomos can be men or women, and each neighborhood takes turns sponsoring the citywide festivals.[1]

The most important festival in any of the neighborhood is that of the patron saint. The night before the church is decorated with lamps and then fireworks are set off to announce the event. The next day, Las Mañanitas is sung to the image, there are a number of Masses and it is possible to receive a "visit" by the image of another saint from another neighborhood. During one of the Masses, there is a ceremony to name a new mayordomo, which is usually attended by mayordomos from other neighborhoods. After this mass, food is offered to all in attendance. If the saint's day falls during the week, it is moved to the following Sunday.[1]

Two annual events particular to San Pedro include the Altepeihuitl and the Tlahuanca. The Altepeilhuitl is an event that takes place on the Sunday before the Thursday marking the ascension of Christ at the Capilla Real. Here images of towns' and neighborhoods' patron saints are adorned with fruit, squash, chili peppers, corn and bread and presented. This tradition dates far back into the colonial period. The Tlahuanca is an event held on the fourth Monday of Lent at the Capilla Real. Originally, it was a festival held on the street, involving drinking to excess. The name comes from the word "tlahuanqui," which means drunk. Today, it is a procession inside the Capilla Real in which wooden crosses are handed out and a host offers food to visitors.[25]

Economy and tourism

San Pedro's traditional economic activity is agriculture and the raising of livestock. Most farming is irrigated and San Pedro has most of the irrigated farmland in the Cholula area. The main economic activities of the city are still commerce and agriculture.[4] Its production is second in importance in the Valley of Puebla. However, the economy is shifting away from agriculture towards small industry, with only 17.4% of the population employed in this area. Residential areas are taking up more land as well. Principle crops include corn, beans, alfalfa, nopal cactus, onions, cilantro, radishes, cauliflower, cabbage, lettuce and cucumbers. There are also various fruits such as pears, plums, apricots, peaches, apples and capulin. There is also extensive floriculture. Livestock includes cattle, goats and pigs. Bee keeping has been growing in importance. Fishing is limited to a small pond called Zerezotla, which is stocked with carp and catfish. There are small areas of pasture and some forest on the Tecajetes Mountain, with pine, oyamel and white cedar.[4]

Industry, mining and construction employ 39% of the population. Natural resources include deposits of clay, sand, gravel and basalt. One of the most important products of the area is the making of hard apple cider and other food processing. There is also the making of bricks, cinderblock and clay roof tiles. Other industries include textiles, chemicals, metals, furniture, ceramics and glass.[4]

Commerce, tourism and services employ 39% of the population. This commerce includes that geared to local, regional and tourist needs.[4] Tourism in San Pedro is based on its history, but the biggest attraction, the Great Pyramid of Cholula is technically located in neighboring San Andrés.[14] This is what has made Cholula one of the better known destinations among foreign travelers to Mexico, as images of the pyramid with the church on top is often used for tourism promotion.[3][19] The second most important attraction, the San Gabriel monastery is in San Pedro along with most of the 37 churches Cholula is famous for. Services are more geared to tourism than those in San Andrés as many establishments are clustered around the city's main square.[4]

Geography

San Pedro Cholula is located in the Valley of Puebla, which is a flat area bordered by the Sierra Nevada to the west, the La Malinche volcano to the north. It is located in the center west of the state of Puebla, with the city of Puebla only about ten kilometers to the east.[4] It extends over 51.03 km2 and borders the municipalities of Juan C. Bonilla, Coronango, Cuautlancingo, San Gregorio Atzompa, San Andrés Cholula, Puebla, San Jerónimo Tecuanipan and Calpan.[4]

The valley floor is an expanse of plains crossed by a number of small rivers, streams and arroyos, with the most significant being the Atoyac River. The Atoyac River has its beginning in the runoff of both the Iztaccíhuatl and Popocatepetl volcanoes.[21] The area has an average altitude of 2,190masl, with a gentle descent from northwest to southeast along the Atoyac River. There are two main elevations: the Zapotecas Mountain, which rises about 200 meters over the valley and the Tecajetes, which rises 210 meters.[4] There is mountain biking and motocross on the Zapotecas Mountain as well as parasailing at the San Bernardino Chalchilhuapan Mountain. Each year, there is a mountain biking event just north of the city in March in three categories: beginners, advanced and expert. The race begins from the main plaza of Cholula and extends for 50 km through a number of small communities.[17] The Zapotecas Mountain is important culturally as well, figuring in a number of local myths and legends, including one about a man who made a pact with a demon in order to obtain money to sponsor a religious festival.[25]

Climate

It has a temperate climate with an average temperature of between 18 and 20C, and typically no more than 20 to 40 days with frost per year. There is a rainy season that lasts from May to October which provides about 800 to 900 mm of rainfall per year. This climate made the area very important agriculturally during the pre Hispanic and colonial eras.[21]

Outlying communities

San Pedro has 22 communities the largest of which are Almoloya, San Cosme Tezintla, Acuexcomac, San Cristóbal Tepontla, San Agustín Calvario, Zacapechpan, San Matías Cocoyotla, San Diego Cuachayotla, and San Francisco Cuapa. These communities primary economic activities are agriculture, floriculture and brick making.[4]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Demi (January 2008). "Los barrios de Cholula" [The neighborhoods of Cholula] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Mexico Desconocido magazine. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Martha Adriana Sáenz Serdio (2004). Vida cural domestica en la parroquia de San Andrés Cholula durante los siglos XVII y XVIII: estudio de caso de arqueología histórica (PDF) (B.A. thesis). Universidad de las Américas Puebla. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Kastelein, Barbara (February 2004). "The Sacred City". Business Mexico. 14 (2). Mexico City: 56–60.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Puebla-San Pedro Cholula". Municipal Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo. 2009. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "Fortalecen Carnaval" [Strengthening Carnival]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. February 22, 2010. p. 18.

- ^ Bermeo, Laura G (October 11, 1998). "Cholula: un concierto de campanas" [Cholula:a concert of bells]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- ^ a b Cordero Vazquez, Donato (2000). Virgen de los Remedios en Cholula [Virgin of the Remedies in Cholula] (in Spanish). Puebla, Mexico: Media IV Impresion Visual. p. 19. ISBN 978-970-94806-6-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Cholula". Let's Go Publications, Inc. 1960–2011. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c Ochoa, Vicente (November 21, 1999). "Cholula y Tonantzintla, tesoros de Puebla" [Cholulaand Tonantzintla, treasures of Puebla]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f "San Pedro Cholula-La Ciudad" [San Pedro Cholula-The City] (in Spanish). Cholula, Mexico: Ayuntamiento de San Pedro Cholula. 2008–2011. Archived from the original on January 7, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "San Pedro Cholula – Historia" [San Pedro Cholula-History] (in Spanish). Cholula, Mexico: Ayuntamiento de San Pedro Cholula. 2008–2011. Archived from the original on November 3, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Juli, Harold D (September 2002). "The Museum of the City of Cholula, Puebla, Mexico". American Anthropologist. 104 (3). Washington DC: 956–958. doi:10.1525/aa.2002.104.3.956.

- ^ Rivas, Francisco (April 10, 2007). "Impiden rescatar vestigios" [Preventing the recovery of remains]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Noble, John (2008). Lonely Planet Mexico. Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet Publications. p. 226.229. ISBN 978-1-86450-089-9. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

Cholula.

- ^ Rivas, Franciso (July 21, 2008). "Refuerzan iglesias contra los saqueos" [Reinforcing churches against sacking]. El Norte (in Spanish). Monterrey, Mexico. p. 19.

- ^ "Cierran por robos iglesias de Cholula" [Cholula churches closing due to robberies]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. July 21, 2010. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "San Pedro Cholula – Guia Turistica" [San Pedro Cholula-Tour Guide] (in Spanish). Cholula, Mexico: Ayuntamiento de San Pedro Cholula. 2008–2011. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c Boy, Alicia (April 13, 2003). "Fin de Semana" [Weekend]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- ^ a b Ibarra, Mariel (July 13, 2002). "Cholula: Antigedad en todos los rincones" [Cholula:Antiquity in every corner]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 16.

- ^ a b Otero, Karla. "Cholula. Ayer y hoy" [Cholula Yesterday and today] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Mexico Desconocido magazine. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bullock Kreger, Meggan M (2010). Urban population dynamics in a preindustrial New World city: Morbidity, mortality, and immigration in postclassic Cholula (PhD thesis). The Pennsylvania State University. Docket AAT 3436082.

- ^ a b c "Puebla-San Andrés Cholula". Municipal Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo. 2009. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Gorenstein, Shirley, ed. (2000). Greater Mesoamerica : The Archaeology of West & Northwest Mexico. Michael Foster (ed). Salt Lake City, UT, USA: University of Utah Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-87480-655-7.

- ^ Kirkwood, Burton (2000). History of Mexico. Westport, CT, USA: Greenwood Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-1-4039-6258-4.

- ^ a b "San Pedro Cholula – Tradiciones y Leyendas" [San Pedro Cholula-Traditions and Legends] (in Spanish). Cholula, Mexico: Ayuntamiento de San Pedro Cholula. 2008–2011. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2011.