Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub[a] (c. 1137 – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin,[b] was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, he spearheaded the Muslim military effort against the Crusader states in the Levant. At the height of his power, the Ayyubid realm spanned Egypt, Syria, Upper Mesopotamia, the Hejaz, Yemen, and Nubia.

Alongside his uncle Shirkuh, a Kurdish mercenary commander in service of the Zengid dynasty,[6] Saladin was sent to Fatimid Egypt in 1164, on the orders of the Zengid ruler Nur ad-Din. With their original purpose being to help restore Shawar as the vizier to the teenage Fatimid caliph al-Adid, a power struggle ensued between Shirkuh and Shawar after the latter was reinstated. Saladin, meanwhile, climbed the ranks of the Fatimid government by virtue of his military successes against Crusader assaults and his personal closeness to al-Adid. After Shawar was assassinated and Shirkuh died in 1169, al-Adid appointed Saladin as vizier. During his tenure, Saladin, a Sunni Muslim, began to undermine the Fatimid establishment; following al-Adid's death in 1171, he abolished the Cairo-based Isma'ili Shia Muslim Fatimid Caliphate and realigned Egypt with the Baghdad-based Sunni Abbasid Caliphate.

In the following years, he led forays against the Crusaders in Palestine, commissioned the successful conquest of Yemen, and staved off pro-Fatimid rebellions in Egypt. Not long after Nur ad-Din died in 1174, Saladin launched his conquest of Syria, peacefully entering Damascus at the request of its governor. By mid-1175, Saladin had conquered Hama and Homs, inviting the animosity of other Zengid lords, who were the official rulers of Syria's principalities; he subsequently defeated the Zengids at the Battle of the Horns of Hama in 1175 and was thereafter proclaimed the 'Sultan of Egypt and Syria' by the Abbasid caliph al-Mustadi. Saladin launched further conquests in northern Syria and Upper Mesopotamia, escaping two attempts on his life by the Assassins before returning to Egypt in 1177 to address local issues there. By 1182, Saladin had completed the conquest of Islamic Syria after capturing Aleppo but failed to take over the Zengid stronghold of Mosul.

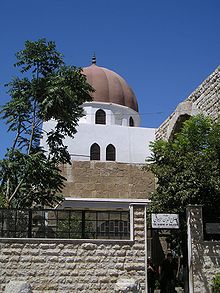

Under Saladin's command, the Ayyubid army defeated the Crusaders at the decisive Battle of Hattin in 1187, capturing Jerusalem and re-establishing Muslim military dominance in the Levant. Although the Crusaders' Kingdom of Jerusalem persisted until the late 13th century, the defeat in 1187 marked a turning point in the Christian military effort against Muslim powers in the region. Saladin died in Damascus in 1193, having given away much of his personal wealth to his subjects; he is buried in a mausoleum adjacent to the Umayyad Mosque. Alongside his significance to Muslim culture, Saladin is revered prominently in Kurdish, Turkic, and Arab culture. He has frequently been described as the most famous Kurdish figure in history.

Early life

| Part of a series on |

| Saladin |

|---|

Saladin was born in Tikrit in present-day Iraq. His personal name was "Yusuf"; "Salah ad-Din" is a laqab, an honorific epithet, meaning "Righteousness of the Faith".[7] His family was of Kurdish ancestry,[8][9][10][11][12] and had originated from the village of Ajdanakan[9] near the city of Dvin in central Armenia.[13][14] He was the son of a Kurdish mercenary, Najm ad-Din Ayyub.[6] The Rawadiya tribe he hailed from had been partially assimilated into the Arabic-speaking world by this time.[15]

In Saladin's era, no scholar had more influence than sheikh Abdul Qadir Gilani, and Saladin was strongly influenced and aided by him and his pupils.[16][17] In 1132, the defeated army of Zengi, Atabeg of Mosul, found their retreat blocked by the Tigris River opposite the fortress of Tikrit, where Saladin's father, Najm ad-Din Ayyub served as the warden. Ayyub provided ferries for the army and gave them refuge in Tikrit. Mujahid ad-Din Bihruz, a former Greek slave who had been appointed as the military governor of northern Mesopotamia for his service to the Seljuks, reprimanded Ayyub for giving Zengi refuge and in 1137 banished Ayyub from Tikrit after his brother Asad ad-Din Shirkuh killed a friend of Bihruz. According to Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad, Saladin was born the same night his family left Tikrit. In 1139, Ayyub and his family moved to Mosul, where Imad ad-Din Zengi acknowledged his debt and appointed Ayyub commander of his fortress in Baalbek. After the death of Zengi in 1146, his son, Nur ad-Din, became the regent of Aleppo and the leader of the Zengids.[18]

Saladin, who now lived in Damascus, was reportedly fond of the city, but information on his early childhood is scarce.[18] About education, Saladin wrote, "Children are brought up in the way in which their elders were brought up". According to his biographers, Anne-Marie Eddé[19] and al-Wahrani, Saladin was able to answer questions on Euclid, the Almagest, arithmetic, and law, but this was an academic ideal. It was his knowledge of the Qur'an and the "sciences of religion" that linked him to his contemporaries;[20] several sources claim that during his studies, he was more interested in religious studies than joining the military.[21] Another factor which may have affected his interest in religion was that, during the First Crusade, Jerusalem was taken by the Christians.[21] In addition to Islam, Saladin knew the genealogies, biographies, and histories of the Arabs, as well as the bloodlines of Arabian horses. More significantly, he knew the Hamasah of Abu Tammam by heart.[20] He spoke Kurdish and Arabic and knew Turkish and Persian.[22][23]

Personality and religious leanings

According to Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad (one of Saladin's contemporary biographers), Saladin was a pious Muslim—he loved hearing Quran recitals, prayed punctually, and "hated the philosophers, those that denied God's attributes, the materialists and those who stubbornly rejected the Holy Law."[26] He was also a supporter of Sufism and a patron of khanqahs (Sufi hostels) in Egypt and Syria, in addition to madrasas that provided orthodox Sunni teachings.[27][26] Above all else he was a devotee of jihad:[28]

The sacred works [Koran, hadith, etc.] are full of passages referring to the jihad. Saladin was more assiduous and zealous in this than in anything else.... Jihad and the suffering involved in it weighed heavily on his heart and his whole being in every limb; he spoke of nothing else, thought only about equipment for the fight, was interested only in those who had taken up arms, had little sympathy with anyone who spoke of anything else or encouraged any other activity.

In 1174, Saladin ordered the arrest of a Sufi mystic, Qadid al-Qaffas (Arabic: قديد القفاص), in Alexandria.[26] In 1191, he ordered his son to execute the Sufi philosopher Yahya al-Suhrawardi, the founder of the Illuminationist current in Islamic philosophy, in Aleppo. Ibn Shaddad, who describes this event as part of his chapter on the sultan's piety, states that Al-Suhrawardi was said to have "rejected the Holy Law and declared it invalid." After consulting with some of the ulama (religious scholars), Saladin ordered al-Suhrawardi's execution.[26] Saladin also opposed the Order of Assassins, an extremist Isma'ili Shi'i sect in Iran and Syria, seeing them as heretics and as being too close with the Crusaders.[26]

Saladin welcomed Asiatic Sufis to Egypt and he and his followers founded and endowed many khanqahs and zawiyas of which al-Maqrizi gives a long list.[29] But it is not yet clear what Saladin's interests in the khanqah actually were and why he specifically wanted Sufis from outside Egypt. The answers to these questions lie in the kinds of Sufis he wished to attract. In addition to requiring that the Sufis come from outside Egypt, the waqfiyya seems to have specified that they be of a very particular type:[30]

The inhabitants of the khanqah were known for religious knowledge and piety and their baraka (blessings) was sought after... The founder stipulated that the khanqah be endowed for the Sufis as a group, those coming from abroad and settling in Cairo and Fustat. If those could not be found, then it would be for the poor jurists, either Shafi'i or Maliki, and Ash'ari in their creed.

Early expeditions

Saladin's military career began under the tutelage of his paternal uncle Asad ad-Din Shirkuh, a prominent military commander under Nur ad-Din, the Zengid emir of Damascus and Aleppo and the most influential teacher of Saladin. In 1163, the vizier to the Fatimid caliph al-Adid, Shawar, had been driven out of Egypt by his rival Dirgham, a member of the powerful Banu Ruzzaik tribe. He asked for military backing from Nur ad-Din, who complied and, in 1164, sent Shirkuh to aid Shawar in his expedition against Dirgham. Saladin, at age 26, went along with them.[35] After Shawar was successfully reinstated as vizier, he demanded that Shirkuh withdraw his army from Egypt for a sum of 30,000 gold dinars, but he refused, insisting it was Nur ad-Din's will that he remain. Saladin's role in this expedition was minor, and it is known that he was ordered by Shirkuh to collect stores from Bilbais prior to its siege by a combined force of Crusaders and Shawar's troops.[36]

After the sacking of Bilbais, the Crusader–Egyptian force and Shirkuh's army were to engage in the Battle of al-Babein on the desert border of the Nile, just west of Giza. Saladin played a major role, commanding the right-wing of the Zengid army, while a force of Kurds commanded the left, and Shirkuh was stationed in the centre. Muslim sources at the time, however, put Saladin in the "baggage of the centre" with orders to lure the enemy into a trap by staging a feigned retreat. The Crusader force enjoyed early success against Shirkuh's troops, but the terrain was too steep and sandy for their horses, and commander Hugh of Caesarea was captured while attacking Saladin's unit. After scattered fighting in little valleys to the south of the main position, the Zengid central force returned to the offensive; Saladin joined in from the rear.[37]

The battle ended in a Zengid victory, and Saladin is credited with having helped Shirkuh in one of the "most remarkable victories in recorded history", according to Ibn al-Athir, although more of Shirkuh's men were killed and the battle is considered by most sources as not a total victory. Saladin and Shirkuh moved towards Alexandria where they were welcomed, given money and arms, and provided a base.[38] Faced by a superior Crusader–Egyptian force attempting to besiege the city, Shirkuh split his army. He and the bulk of his force withdrew from Alexandria, while Saladin was left with the task of guarding the city, where he was besieged.[39]

In Egypt

Vizier of Egypt

Shirkuh was in a power struggle over Egypt with Shawar and Amalric I of Jerusalem in which Shawar requested Amalric's assistance. In 1169, Shawar was reportedly assassinated by Saladin, and Shirkuh died later that year.[41] Following his death, a number of candidates were considered for the role of vizier to al-Adid, most of whom were ethnic Kurds. Their ethnic solidarity came to shape the Ayyubid family's actions in their political career. Saladin and his close associates were wary of Turkish influence. On one occasion Isa al-Hakkari, a Kurdish lieutenant of Saladin, urged a candidate for the viziership, Emir Qutb ad-Din al-Hadhbani, to step aside by arguing that "both you and Saladin are Kurds and you will not let the power pass into the hands of the Turks".[42] Nur ad-Din chose a successor for Shirkuh, but al-Adid appointed Saladin to replace Shawar as vizier.[43]

The reasoning behind the Shia caliph al-Adid's selection of Saladin, a Sunni, varies. Ibn al-Athir claims that the caliph chose him after being told by his advisers that "there is no one weaker or younger" than Saladin, and "not one of the emirs [commanders] obeyed him or served him". However, according to this version, after some bargaining, he was eventually accepted by the majority of the emirs. Al-Adid's advisers were also suspected of promoting Saladin in an attempt to split the Syria-based Zengids. Al-Wahrani wrote that Saladin was selected because of the reputation of his family in their "generosity and military prowess". Imad ad-Din wrote that after the brief mourning period for Shirkuh, during which "opinions differed", the Zengid emirs decided upon Saladin and forced the caliph to "invest him as vizier". Although positions were complicated by rival Muslim leaders, the bulk of the Syrian commanders supported Saladin because of his role in the Egyptian expedition, in which he gained a record of military qualifications.[44]

Inaugurated as vizier on 26 March, Saladin repented "wine-drinking and turned from frivolity to assume the dress of religion", according to Arabic sources of the time.[45] Having gained more power and independence than ever before in his career, he still faced the issue of ultimate loyalty between al-Adid and Nur ad-Din. Later in the year, a group of Egyptian soldiers and emirs attempted to assassinate Saladin, but having already known of their intentions thanks to his intelligence chief Ali ibn Safyan, he had the chief conspirator, Naji, Mu'tamin al-Khilafa—the civilian controller of the Fatimid Palace—arrested and killed. The day after, 50,000 Black African soldiers from the regiments of the Fatimid army opposed to Saladin's rule, along with Egyptian emirs and commoners, staged a revolt. By 23 August, Saladin had decisively quelled the uprising, and never again had to face a military challenge from Cairo.[46]

Towards the end of 1169, Saladin, with reinforcements from Nur ad-Din, defeated a massive Crusader-Byzantine force near Damietta. Afterwards, in the spring of 1170, Nur ad-Din sent Saladin's father to Egypt in compliance with Saladin's request, as well as encouragement from the Baghdad-based Abbasid caliph, al-Mustanjid, who aimed to pressure Saladin in deposing his rival caliph, al-Ad.[47] Saladin himself had been strengthening his hold on Egypt and widening his support base there. He began granting his family members high-ranking positions in the region; he ordered the construction of a college for the Maliki branch of Sunni Islam in the city, as well as one for the Shafi'i denomination to which he belonged in al-Fustat.[48]

After establishing himself in Egypt, Saladin launched a campaign against the Crusaders, besieging Darum in 1170.[49] Amalric withdrew his Templar garrison from Gaza to assist him in defending Darum, but Saladin evaded their force and captured Gaza in 1187. In 1191 Saladin destroyed the fortifications in Gaza built by King Baldwin III for the Knights Templar.[50] It is unclear exactly when, but during that same year, he attacked and captured the Crusader castle of Eilat, built on an island off the head of the Gulf of Aqaba. It did not pose a threat to the passage of the Muslim navy but could harass smaller parties of Muslim ships, and Saladin decided to clear it from his path.[49]

Sultan of Egypt

According to Imad ad-Din, Nur ad-Din wrote to Saladin in June 1171, telling him to reestablish the Abbasid caliphate in Egypt, which Saladin coordinated two months later after additional encouragement by Najm ad-Din al-Khabushani, the Shafi'i faqih, who vehemently opposed Shia rule in the country. Several Egyptian emirs were thus killed, but al-Adid was told that they were killed for rebelling against him. He then fell ill or was poisoned according to one account. While ill, he asked Saladin to pay him a visit to request that he take care of his young children, but Saladin refused, fearing treachery against the Abbasids, and is said to have regretted his action after realizing what al-Adid had wanted.[51] He died on 13 September, and five days later, the Abbasid khutba was pronounced in Cairo and al-Fustat, proclaiming al-Mustadi as caliph.[52]

On 25 September, Saladin left Cairo to take part in a joint attack on Kerak and Montréal, the desert castles of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, with Nur ad-Din who would attack from Syria. Prior to arriving at Montreal, Saladin however withdrew back to Cairo as he received the reports that in his absence the Crusader leaders had increased their support to the traitors inside Egypt to attack Saladin from within and lessen his power, especially the Fatimid who started plotting to restore their past glory. Because of this, Nur ad-Din went on alone.[53]

During the summer of 1173, a Nubian army along with a contingent of Armenian former Fatimid troops were reported on the Egyptian border, preparing for a siege against Aswan. The emir of the city had requested Saladin's assistance and was given reinforcements under Turan-Shah, Saladin's brother. Consequently, the Nubians departed; but returned in 1173 and were again driven off. This time, Egyptian forces advanced from Aswan and captured the Nubian town of Ibrim. Saladin sent a gift to Nur ad-Din, who had been his friend and teacher, 60,000 dinars, "wonderful manufactured goods", some jewels, and an elephant. While transporting these goods to Damascus, Saladin took the opportunity to ravage the Crusader countryside. He did not press an attack against the desert castles but attempted to drive out the Muslim Bedouins who lived in Crusader territory with the aim of depriving the Franks of guides.[54]

On 31 July 1173, Saladin's father Ayyub was wounded in a horse-riding accident, ultimately causing his death on 9 August.[55] In 1174, Saladin sent Turan-Shah to conquer Yemen to allocate it and its port Aden to the territories of the Ayyubid Dynasty.

Conquest of Syria

Conquest of Damascus

In the early summer of 1174, Nur ad-Din was mustering an army, sending summons to Mosul, Diyar Bakr, and the Jazira in an apparent preparation of an attack against Saladin's Egypt. The Ayyubids held a council upon the revelation of these preparations to discuss the possible threat and Saladin collected his own troops outside Cairo. On 15 May, Nur ad-Din died after falling ill the previous week and his power was handed to his eleven-year-old son as-Salih Ismail al-Malik. His death left Saladin with political independence and in a letter to as-Salih, he promised to "act as a sword" against his enemies and referred to the death of his father as an "earthquake shock".[56]

In the wake of Nur ad-Din's death, Saladin faced a difficult decision; he could move his army against the Crusaders from Egypt or wait until invited by as-Salih in Syria to come to his aid and launch a war from there. He could also take it upon himself to annex Syria before it could possibly fall into the hands of a rival, but he feared that attacking a land that formerly belonged to his master—forbidden in the Islamic principles in which he believed—could portray him as hypocritical, thus making him unsuitable for leading the war against the Crusaders. Saladin saw that in order to acquire Syria, he needed either an invitation from as-Salih or to warn him that potential anarchy could give rise to danger from the Crusaders.[57]

When as-Salih was removed to Aleppo in August, Gumushtigin, the emir of the city and a captain of Nur ad-Din's veterans assumed guardianship over him. The emir prepared to unseat all his rivals in Syria and the Jazira, beginning with Damascus. In this emergency, the emir of Damascus appealed to Saif ad-Din of Mosul (a cousin of Gumushtigin) for assistance against Aleppo, but he refused, forcing the Syrians to request the aid of Saladin, who complied.[58] Saladin rode across the desert with 700 picked horsemen, passing through al-Kerak then reaching Bosra. According to his own account, was joined by "emirs, soldiers, and Bedouins—the emotions of their hearts to be seen on their faces."[59] On 23 November, he arrived in Damascus amid general acclamation and rested at his father's old home there, until the gates of the Citadel of Damascus,[58] whose commander Raihan initially refused to surrender, were opened to Saladin four days later, after a brief siege by his brother Tughtakin ibn Ayyub.[60] He installed himself in the castle and received the homage and salutations of the inhabitants.[61]

Further conquests in Syria

Leaving his brother Tughtakin ibn Ayyub as Governor of Damascus, Saladin proceeded to reduce other cities that had belonged to Nur ad-Din, but were now practically independent. His army conquered Hama with relative ease, but avoided attacking Homs because of the strength of its citadel.[62] Saladin moved north towards Aleppo, besieging it on 30 December after Gumushtigin refused to abdicate his throne.[63] As-Salih, fearing capture by Saladin, came out of his palace and appealed to the inhabitants not to surrender him and the city to the invading force. One of Saladin's chroniclers claimed "the people came under his spell".[64]

Gumushtigin requested Rashid ad-Din Sinan, chief da'i of the Assassins of Syria, who were already at odds with Saladin since he replaced the Fatimids of Egypt, to assassinate Saladin in his camp.[65] On 11 May 1175, a group of thirteen Assassins easily gained admission into Saladin's camp, but were detected immediately before they carried out their attack by Nasih ad-Din Khumartekin of Abu Qubays. One was killed by one of Saladin's generals and the others were slain while trying to escape.[64][66][67] To deter Saladin's progress, Raymond of Tripoli gathered his forces by Nahr al-Kabir, where they were well placed for an attack on Muslim territory. Saladin later moved toward Homs instead, but retreated after being told a relief force was being sent to the city by Saif ad-Din.[68][69]

Meanwhile, Saladin's rivals in Syria and Jazira waged a propaganda war against him, claiming he had "forgotten his own condition [servant of Nur ad-Din]" and showed no gratitude for his old master by besieging his son, rising "in rebellion against his Lord". Saladin aimed to counter this propaganda by ending the siege, claiming that he was defending Islam from the Crusaders; his army returned to Hama to engage a Crusader force there. The Crusaders withdrew beforehand and Saladin proclaimed it "a victory opening the gates of men's hearts".[68] Soon after, Saladin entered Homs and captured its citadel in March 1175, after stubborn resistance from its defenders.[70]

Saladin's successes alarmed Saif ad-Din. As head of the Zengids, including Gumushtigin, he regarded Syria and Mesopotamia as his family estate and was angered when Saladin attempted to usurp his dynasty's holdings. Saif ad-Din mustered a large army and dispatched it to Aleppo, whose defenders anxiously had awaited them. The combined forces of Mosul and Aleppo marched against Saladin in Hama. Heavily outnumbered, Saladin initially attempted to make terms with the Zengids by abandoning all conquests north of the Damascus province, but they refused, insisting he return to Egypt. Seeing that confrontation was unavoidable, Saladin prepared for battle, taking up a superior position at the Horns of Hama, hills by the gorge of the Orontes River. On 13 April 1175, the Zengid troops marched to attack his forces, but soon found themselves surrounded by Saladin's Ayyubid veterans, who crushed them. The battle ended in a decisive victory for Saladin, who pursued the Zengid fugitives to the gates of Aleppo, forcing as-Salih's advisers to recognize Saladin's control of the provinces of Damascus, Homs, and Hama, as well as a number of towns outside Aleppo such as Ma'arat al-Numan.[71]

After his victory against the Zengids, Saladin proclaimed himself king and suppressed the name of as-Salih in Friday prayers and Islamic coinage. From then on, he ordered prayers in all the mosques of Syria and Egypt as the sovereign king and he issued at the Cairo mint gold coins bearing his official title—al-Malik an-Nasir Yusuf Ayyub, ala ghaya "the King Strong to Aid, Joseph son of Job; exalted be the standard." The Abbasid caliph in Baghdad graciously welcomed Saladin's assumption of power and declared him "Sultan of Egypt and Syria". The Battle of Hama did not end the contest for power between the Ayyubids and the Zengids, with the final confrontation occurring in the spring of 1176. Saladin had gathered massive reinforcements from Egypt while Saif ad-Din was levying troops among the minor states of Diyarbakir and al-Jazira.[72] When Saladin crossed the Orontes, leaving Hama, the sun was eclipsed. He viewed this as an omen, but he continued his march north. He reached the Sultan's Mound, roughly 25 km (16 mi) from Aleppo, where his forces encountered Saif ad-Din's army. A hand-to-hand fight ensued and the Zengids managed to plough Saladin's left-wing, driving it before him when Saladin himself charged at the head of the Zengid guard. The Zengid forces panicked and most of Saif ad-Din's officers ended up being killed or captured—Saif ad-Din narrowly escaped. The Zengid army's camp, horses, baggage, tents, and stores were seized by the Ayyubids. The Zengid prisoners of war, however, were given gifts and freed. All of the booty from the Ayyubid victory was accorded to the army, Saladin not keeping anything himself.[73]

He continued towards Aleppo, which still closed its gates to him, halting before the city. On the way, his army took Buza'a and then captured Manbij. From there, they headed west to besiege the fortress of A'zaz on 15 May. Several days later, while Saladin was resting in one of his captain's tents, an Assassin rushed forward at him and struck at his head with a knife. The cap of his head armour was not penetrated and he managed to grip the Assassin's hand—the dagger only slashing his gambeson—and the assailant was soon killed. Saladin was unnerved at the attempt on his life, which he accused Gumushtugin and the Assassins of plotting, and so increased his efforts in the siege.[74]

A'zaz capitulated on 21 June, and Saladin then hurried his forces to Aleppo to punish Gumushtigin. His assaults were again resisted, but he managed to secure not only a truce, but a mutual alliance with Aleppo, in which Gumushtigin and as-Salih were allowed to continue their hold on the city, and in return, they recognized Saladin as the sovereign over all of the dominions he conquered. The emirs of Mardin and Keyfa, the Muslim allies of Aleppo, also recognised Saladin as the King of Syria. When the treaty was concluded, the younger sister of as-Salih came to Saladin and requested the return of the Fortress of A'zaz; he complied and escorted her back to the gates of Aleppo with numerous presents.[74]

Campaign against the Assassins

Saladin had by now agreed to truces with his Zengid rivals and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (the latter occurred in the summer of 1175), but faced a threat from the Isma'ili sect known as the Assassins, led by Rashid ad-Din Sinan. Based in the an-Nusayriyah Mountains, they commanded nine fortresses, all built on high elevations. As soon as he dispatched the bulk of his troops to Egypt, Saladin led his army into the an-Nusayriyah range in August 1176. He retreated the same month, after laying waste to the countryside, but failing to conquer any of the forts. Most Muslim historians claim that Saladin's uncle, the governor of Hama, mediated a peace agreement between him and Sinan.[75][76]

Saladin had his guards supplied with link lights and had chalk and cinders strewed around his tent outside Masyaf—which he was besieging—to detect any footsteps by the Assassins.[77] According to this version, one night Saladin's guards noticed a spark glowing down the hill of Masyaf and then vanishing among the Ayyubid tents. Presently, Saladin awoke to find a figure leaving the tent. He saw that the lamps were displaced and beside his bed laid hot scones of the shape peculiar to the Assassins with a note at the top pinned by a poisoned dagger. The note threatened that he would be killed if he did not withdraw from his assault. Saladin gave a loud cry, exclaiming that Sinan himself was the figure that had left the tent.[77]

Another version claims that Saladin hastily withdrew his troops from Masyaf because they were urgently needed to fend off a Crusader force in the vicinity of Mount Lebanon.[76] In reality, Saladin sought to form an alliance with Sinan and his Assassins, consequently depriving the Crusaders of a potent ally against him.[78] Viewing the expulsion of the Crusaders as a mutual benefit and priority, Saladin and Sinan maintained cooperative relations afterwards, the latter dispatching contingents of his forces to bolster Saladin's army in a number of decisive subsequent battlefronts.[79]

Return to Cairo and forays in Palestine

After leaving the an-Nusayriyah Mountains, Saladin returned to Damascus and had his Syrian soldiers return home. He left Turan Shah in command of Syria and left for Egypt with only his personal followers, reaching Cairo on 22 September. Having been absent for roughly two years, he had much to organize and supervise in Egypt, namely fortifying and reconstructing Cairo. The city walls were repaired and their extensions laid out, while the construction of the Cairo Citadel was commenced.[78] The 280 feet (85 m) deep Bir Yusuf ("Joseph's Well") was built on Saladin's orders. The chief public work he commissioned outside of Cairo was the large bridge at Giza, which was intended to form an outwork of defence against a potential Moorish invasion.[81]

Saladin remained in Cairo supervising its improvements, building colleges such as the Madrasa of the Sword Makers and ordering the internal administration of the country. In November 1177, he set out upon a raid into Palestine; the Crusaders had recently forayed into the territory of Damascus, so Saladin saw the truce as no longer worth preserving. The Christians sent a large portion of their army to besiege the fortress of Harim north of Aleppo, so southern Palestine bore few defenders.[81] Saladin found the situation ripe and marched to Ascalon, which he referred to as the "Bride of Syria". William of Tyre recorded that the Ayyubid army consisted of 26,000 soldiers, of which 8,000 were elite forces and 18,000 were black soldiers from Sudan. This army proceeded to raid the countryside, sack Ramla and Lod, and disperse themselves as far as the Gates of Jerusalem.[82]

Battles and truce with Baldwin

The Ayyubids allowed Baldwin IV of Jerusalem to enter Ascalon with his famous Gaza-based Knights Templar without taking any precautions against a sudden attack. Although the Crusader force consisted of only 375 knights, Saladin hesitated to ambush them because of the presence of highly skilled templar generals. On 25 November, while the greater part of the Ayyubid army was absent, Saladin and his men were surprised near Ramla in the battle of Montgisard (possibly at Gezer, also known as Tell Jezar). Before they could form up, the Templar force hacked the Ayyubid army down by body-to-body of sword. Initially, Saladin attempted to organize his men into battle order, but as his bodyguards were being killed, he saw that defeat was inevitable and so with a small remnant of his troops mounted a swift camel, riding all the way to the territories of Egypt.[83]

Not discouraged by his defeat at Montgisard, Saladin was prepared to fight the Crusaders once again. In the spring of 1178, he was encamped under the walls of Homs, and a few skirmishes occurred between his generals and the Crusader army. His forces in Hama won a victory over their enemy and brought the spoils, together with many prisoners of war, to Saladin who ordered the captives to be beheaded for "plundering and laying waste the lands of the Faithful". He spent the rest of the year in Syria without a confrontation with his enemies.[84]

Saladin's intelligence services reported to him that the Crusaders were planning a raid into Syria. He ordered one of his generals, Farrukh-Shah, to guard the Damascus frontier with a thousand of his men to watch for an attack, then to retire, avoiding battle, and to light warning beacons on the hills, after which Saladin would march out. In April 1179, the Crusaders and Templars led by King Baldwin expected no resistance and waited to launch a surprise attack on Muslim herders grazing their herds and flocks east of the Golan Heights. Baldwin advanced too rashly in pursuit of Farrukh-Shah's force, which was concentrated southeast of Quneitra and was subsequently defeated by the Ayyubids. With this victory, Saladin decided to call in more troops from Egypt; he requested al-Adil to dispatch 1,500 horsemen.[85]

In the summer of 1179, King Baldwin had set up an outpost on the road to Damascus and aimed to fortify a passage over the Jordan River, known as Jacob's Ford, that commanded the approach to the Banias plain (the plain was divided by the Muslims and the Christians). Saladin had offered 100,000 gold pieces to Baldwin to abandon the project, which was particularly offensive to the Muslims, but to no avail. He then resolved to destroy the fortress, called "Chastellet" and defended by the Templars knights, moving his headquarters to Banias. As the Crusaders hurried down to attack the Muslim forces, they fell into disorder, with the infantry falling behind. Despite early success, they pursued the Muslims far enough to become scattered, and Saladin took advantage by rallying his troops and charging at the Crusaders. The engagement ended in a decisive Ayyubid victory, and many high-ranking knights were captured. Saladin then moved to besiege the fortress, which fell on 30 August 1179.[86]

In the spring of 1180, while Saladin was in the area of Safad, anxious to commence a vigorous campaign against the Kingdom of Jerusalem, King Baldwin sent messengers to him with proposals of peace. Because droughts and bad harvests hampered his commissariat, Saladin agreed to a truce. Raymond of Tripoli denounced the truce but was compelled to accept after an Ayyubid raid on his territory in May and upon the appearance of Saladin's naval fleet off the port of Tartus.[87]

Domestic affairs

Obv.: "The Prince, Defender, Honor of the world [and] the faith"; in margin: "Yusuf bin Ayyub, Struck in Damascus, Year three and eighty and five hundred".

Rev.: "The Imam al-Nāṣir li-Dīn Allāh, Commander of the Faithful"; in margin: "There is no deity except God alone, Muhammad is the messenger of God".[88]

In June 1180, Saladin hosted a reception for Nur ad-Din Muhammad, the Artuqid emir of Keyfa, at Geuk Su, in which he presented him and his brother Abu Bakr with gifts, valued at over 100,000 dinars according to Imad ad-Din. This was intended to cement an alliance with the Artuqids and to impress other emirs in Mesopotamia and Anatolia. Previously, Saladin offered to mediate relations between Nur ad-Din and Kilij Arslan II—the Seljuk sultan of Rûm—after the two came into conflict. The latter demanded that Nur ad-Din return the lands given to him as a dowry for marrying his daughter when he received reports that she was being abused and used to gain Seljuk territory. Nur ad-Din asked Saladin to mediate the issue, but Arslan refused.[89]

After Nur ad-Din and Saladin met at Geuk Su, the top Seljuk emir, Ikhtiyar ad-Din al-Hasan, confirmed Arslan's submission, after which an agreement was drawn up. Saladin was later enraged when he received a message from Arslan accusing Nur ad-Din of more abuses against his daughter. He threatened to attack the city of Malatya, saying, "it is two days march for me and I shall not dismount [my horse] until I am in the city." Alarmed at the threat, the Seljuks pushed for negotiations. Saladin felt that Arslan was correct to care for his daughter, but Nur ad-Din had taken refuge with him, and therefore he could not betray his trust. It was finally agreed that Arslan's daughter would be sent away for a year and if Nur ad-Din failed to comply, Saladin would move to abandon his support for him.[89]

Leaving Farrukh-Shah in charge of Syria, Saladin returned to Cairo at the beginning of 1181. According to Abu Shama, he intended to spend the fast of Ramadan in Egypt and then make the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca in the summer. For an unknown reason, he apparently changed his plans regarding the pilgrimage and was seen inspecting the Nile River banks in June. He was again embroiled with the Bedouin; he removed two-thirds of their fiefs to use as compensation for the fief-holders at Fayyum. The Bedouin were also accused of trading with the Crusaders and, consequently, their grain was confiscated and they were forced to migrate westward. Later, Ayyubid warships were deployed against Bedouin river pirates, who were plundering the shores of Lake Tanis.[90]

In the summer of 1181, Saladin's former palace administrator Baha ad-Din Qaraqush led a force to arrest Majd ad-Din—a former deputy of Turan-Shah in the Yemeni town of Zabid—while he was entertaining Imad ad-Din al-Ishfahani at his estate in Cairo. Saladin's intimates accused Majd ad-Din of misappropriating the revenues of Zabid, but Saladin himself believed there was no evidence to back the allegations. He had Majd ad-Din released in return for a payment of 80,000 dinars. In addition, other sums were to be paid to Saladin's brothers al-Adil and Taj al-Muluk Buri. The controversial detainment of Majd ad-Din was a part of the larger discontent associated with the aftermath of Turan-Shah's departure from Yemen. Although his deputies continued to send him revenues from the province, centralized authority was lacking and an internal quarrel arose between Izz ad-Din Uthman of Aden and Hittan of Zabid. Saladin wrote in a letter to al-Adil: "this Yemen is a treasure house ... We conquered it, but up to this day we have had no return and no advantage from it. There have been only innumerable expenses, the sending out of troops ... and expectations which did not produce what was hoped for in the end."[91]

Imperial expansions

Campaign against the Franks and War with the Zengids

Saif ad-Din had died earlier in June 1181 and his brother Izz ad-Din inherited leadership of Mosul.[93] On 4 December, the crown prince of the Zengids, as-Salih, died in Aleppo. Prior to his death, he had his chief officers swear an oath of loyalty to Izz ad-Din, as he was the only Zengid ruler strong enough to oppose Saladin. Izz ad-Din was welcomed in Aleppo, but possessing it and Mosul put too great of a strain on his abilities. He thus, handed Aleppo to his brother Imad ad-Din Zangi, in exchange for Sinjar. Saladin offered no opposition to these transactions in order to respect the treaty he previously made with the Zengids.[94]

On 11 May 1182, Saladin, along with half of the Egyptian Ayyubid army and numerous non-combatants, left Cairo for Syria. On the evening before he departed, he sat with his companions and the tutor of one of his sons quoted a line of poetry: "enjoy the scent of the ox-eye plant of Najd, for after this evening it will come no more". Saladin took this as an evil omen and he never saw Egypt again.[93] Knowing that Crusader forces were massed upon the frontier to intercept him, he took the desert route across the Sinai Peninsula to Ailah at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba. Meeting no opposition, Saladin ravaged the countryside of Montreal, whilst Baldwin's forces watched on, refusing to intervene.[95] He arrived in Damascus in June to learn that Farrukh-Shah had attacked the Galilee, sacking Daburiyya and capturing Habis Jaldek, a fortress of great importance to the Crusaders. In July, Saladin led his army across the Jordan and into Galilee, where he marched south to sack Bethsan. He was met by a substantial Crusader force in an inconclusive battle near Belvoir Castle, but he was unable to destroy the Christian army and could not logistically sustain his own army any longer, so he withdrew across the river. In August, he passed through the Beqaa Valley to Beirut, where he rendezvoused with the Egyptian fleet and laid siege to the city. Failing to make any headway, he withdrew after a few days to deal with matters in Mesopotamia.[96]

Kukbary (Muzaffar ad-Din Gökböri), the emir of Harran, invited Saladin to occupy the Jazira region, making up northern Mesopotamia. He complied and the truce between him and the Zengids officially ended in September 1182.[97] Prior to his march to Jazira, tensions had grown between the Zengid rulers of the region, primarily concerning their unwillingness to pay deference to Mosul.[98] Before he crossed the Euphrates, Saladin besieged Aleppo for three days, signaling that the truce was over.[97]

Once he reached Bira, near the river, he was joined by Kukbary and Nur ad-Din of Hisn Kayfa and the combined forces captured the cities of Jazira, one after the other. First, Edessa fell, followed by Saruj, then Raqqa, Qirqesiya and Nusaybin.[99] Raqqa was an important crossing point and held by Qutb ad-Din Inal, who had lost Manbij to Saladin in 1176. Upon seeing the large size of Saladin's army, he made little effort to resist and surrendered on the condition that he would retain his property. Saladin promptly impressed the inhabitants of the town by publishing a decree that ordered a number of taxes to be canceled and erased all mention of them from treasury records, stating "the most miserable rulers are those whose purses are fat and their people thin". From Raqqa, he moved to conquer al-Fudain, al-Husain, Maksim, Durain, 'Araban, and Khabur—all of which swore allegiance to him.[100]

Saladin proceeded to take Nusaybin which offered no resistance. A medium-sized town, Nusaybin was not of great importance, but it was located in a strategic position between Mardin and Mosul and within easy reach of Diyarbakir.[101] In the midst of these victories, Saladin received word that the Crusaders were raiding the villages of Damascus. He replied, "Let them... whilst they knock down villages, we are taking cities; when we come back, we shall have all the more strength to fight them."[97] Meanwhile, in Aleppo, the emir of the city Zangi raided Saladin's cities to the north and east, such as Balis, Manbij, Saruj, Buza'a, al-Karzain. He also destroyed his own citadel at A'zaz to prevent it from being used by the Ayyubids if they were to conquer it.[101]

Fight for Mosul

As Saladin approached Mosul, he faced the issue of taking over a large city and justifying the action.[103] The Zengids of Mosul appealed to an-Nasir, the Abbasid caliph at Baghdad whose vizier favored them. An-Nasir sent Badr al-Badr (a high-ranking religious figure) to mediate between the two sides. Saladin arrived at the city on 10 November 1182. Izz ad-Din would not accept his terms because he considered them disingenuous and extensive, and Saladin immediately laid siege to the heavily fortified city.[104]

After several minor skirmishes and a stalemate in the siege that was initiated by the caliph, Saladin intended to find a way to withdraw without damage to his reputation while still keeping up some military pressure. He decided to attack Sinjar, which was held by Izz ad-Din's brother Sharaf ad-Din. It fell after a 15-day siege on 30 December.[105] Saladin's soldiers broke their discipline, plundering the city; Saladin managed to protect the governor and his officers only by sending them to Mosul. After establishing a garrison at Sinjar, he awaited a coalition assembled by Izz ad-Din consisting of his forces, those from Aleppo, Mardin, and Armenia.[106] Saladin and his army met the coalition at Harran in February 1183, but on hearing of his approach, the latter sent messengers to Saladin asking for peace. Each force returned to their cities and al-Fadil wrote: "They [Izz ad-Din's coalition] advanced like men, like women they vanished."[107]

On 2 March, al-Adil from Egypt wrote to Saladin that the Crusaders had struck the "heart of Islam". Raynald de Châtillon had sent ships to the Gulf of Aqaba to raid towns and villages off the coast of the Red Sea. It was not an attempt to extend the Crusader influence into that sea or to capture its trade routes, but merely a piratical move.[108] Nonetheless, Imad ad-Din writes the raid was alarming to the Muslims because they were not accustomed to attacks on that sea, and Ibn al-Athir adds that the inhabitants had no experience with the Crusaders either as fighters or traders.[109]

Ibn Jubair was told that sixteen Muslim ships were burnt by the Crusaders, who then captured a pilgrim ship and caravan at Aidab. He also reported that they intended to attack Medina and remove Muhammad's body. Al-Maqrizi added to the rumor by claiming Muhammad's tomb was going to be relocated to Crusader territory so Muslims would make pilgrimages there. Al-Adil had his warships moved from Fustat and Alexandria to the Red Sea under the command of an Armenian mercenary Lu'lu. They broke the Crusader blockade, destroyed most of their ships, and pursued and captured those who anchored and fled into the desert.[110] The surviving Crusaders, numbered at 170, were ordered to be killed by Saladin in various Muslim cities.[111]

From the point of view of Saladin, in terms of territory, the war against Mosul was going well, but he still failed to achieve his objectives and his army was shrinking; Taqi ad-Din took his men back to Hama, while Nasir ad-Din Muhammad and his forces had left. This encouraged Izz ad-Din and his allies to take the offensive. The previous coalition regrouped at Harzam some 140 km from Harran. In early April, without waiting for Nasir ad-Din, Saladin and Taqi ad-Din commenced their advance against the coalition, marching eastward to Ras al-Ein unhindered.[114] By late April, after three days of "actual fighting", according to Saladin, the Ayyubids had captured Amid. He handed the city to Nur ad-Din Muhammad together with its stores, which consisted of 80,000 candles, a tower full of arrowheads, and 1,040,000 books. In return for a diploma—granting him the city, Nur ad-Din swore allegiance to Saladin, promising to follow him in every expedition in the war against the Crusaders, and repairing the damage done to the city. The fall of Amid, in addition to territory, convinced Il-Ghazi of Mardin to enter the service of Saladin, weakening Izz ad-Din's coalition.[115]

Saladin attempted to gain the Caliph an-Nasir's support against Izz ad-Din by sending him a letter requesting a document that would give him legal justification for taking over Mosul and its territories. Saladin aimed to persuade the caliph claiming that while he conquered Egypt and Yemen under the flag of the Abbasids, the Zengids of Mosul openly supported the Seljuks (rivals of the caliphate) and only came to the caliph when in need. He also accused Izz ad-Din's forces of disrupting the Muslim "Holy War" against the Crusaders, stating "they are not content not to fight, but they prevent those who can". Saladin defended his own conduct claiming that he had come to Syria to fight the Crusaders, end the heresy of the Assassins, and stop the wrong-doing of the Muslims. He also promised that if Mosul was given to him, it would lead to the capture of Jerusalem, Constantinople, Georgia, and the lands of the Almohads in the Maghreb, "until the word of God is supreme and the Abbasid caliphate has wiped the world clean, turning the churches into mosques". Saladin stressed that all this would happen by the will of God, and instead of asking for financial or military support from the caliph, he would capture and give the caliph the territories of Tikrit, Daquq, Khuzestan, Kish Island, and Oman.[116]

Possession of Aleppo

Saladin turned his attention from Mosul to Aleppo, sending his brother Taj al-Muluk Buri to capture Tell Khalid, 130 km northeast of the city. A siege was set, but the governor of Tell Khalid surrendered upon the arrival of Saladin himself on 17 May before a siege could take place. According to Imad ad-Din, after Tell Khalid, Saladin took a detour northwards to Aintab, but he gained possession of it when his army turned towards it, allowing him to quickly move backward another c. 100 km towards Aleppo. On 21 May, he camped outside the city, positioning himself east of the Citadel of Aleppo, while his forces encircled the suburb of Banaqusa to the northeast and Bab Janan to the west. He stationed his men dangerously close to the city, hoping for an early success.[117]

Zangi did not offer long resistance. He was unpopular with his subjects and wished to return to his Sinjar, the city he governed previously. An exchange was negotiated where Zangi would hand over Aleppo to Saladin in return for the restoration of his control of Sinjar, Nusaybin, and Raqqa. Zangi would hold these territories as Saladin's vassals in terms of military service. On 12 June, Aleppo was formally placed in Ayyubid hands.[118] The people of Aleppo had not known about these negotiations and were taken by surprise when Saladin's standard was hoisted over the citadel. Two emirs, including an old friend of Saladin, Izz ad-Din Jurduk, welcomed and pledged their service to him. Saladin replaced the Hanafi courts with Shafi'i administration, despite a promise that he would not interfere in the religious leadership of the city. Although he was short of money, Saladin also allowed the departing Zangi to take all the stores of the citadel that he could travel with and to sell the remainder—which Saladin purchased himself. In spite of his earlier hesitation to go through with the exchange, he had no doubts about his success, stating that Aleppo was "the key to the lands" and "this city is the eye of Syria and the citadel is its pupil".[119] For Saladin, the capture of the city marked the end of over eight years of waiting since he told Farrukh-Shah that "we have only to do the milking and Aleppo will be ours".[120]

After spending one night in Aleppo's citadel, Saladin marched to Harim, near the Crusader-held Antioch. The city was held by Surhak, a "minor mamluk". Saladin offered him the city of Busra and property in Damascus in exchange for Harim, but when Surhak asked for more, his own garrison in Harim forced him out. He was arrested by Saladin's deputy Taqi ad-Din on allegations that he was planning to cede Harim to Bohemond III of Antioch. When Saladin received its surrender, he proceeded to arrange the defense of Harim from the Crusaders. He reported to the caliph and his own subordinates in Yemen and Baalbek that he was going to attack the Armenians. Before he could move, however, there were a number of administrative details to be settled. Saladin agreed to a truce with Bohemond in return for Muslim prisoners being held by him and then he gave A'zaz to Alam ad-Din Suleiman and Aleppo to Saif ad-Din al-Yazkuj—the former was an emir of Aleppo who joined Saladin and the latter was a former mamluk of Shirkuh who helped rescue him from the assassination attempt at A'zaz.[121]

Wars against Crusaders

Crusader attacks provoked further responses by Saladin. Raynald of Châtillon, in particular, harassed Muslim trading and pilgrimage routes with a fleet on the Red Sea, a water route that Saladin needed to keep open. Raynald threatened to attack the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. On 29 September 1183, Saladin crossed the Jordan River to attack Beisan, which was found to be empty. The next day his forces sacked and burned the town and moved westwards. They intercepted Crusader reinforcements from Karak and Shaubak along the Nablus road and took prisoners. Meanwhile, the main Crusader force under Guy of Lusignan moved from Sepphoris to al-Fula. Saladin sent out 500 skirmishers to harass their forces, and he himself marched to Ain Jalut. When the Crusader force—reckoned to be the largest the kingdom ever produced from its own resources, but still outmatched by the Muslims—advanced, the Ayyubids unexpectedly moved down the stream of Ain Jalut. After a few Ayyubid raids—including attacks on Zir'in, Forbelet, and Mount Tabor—the Crusaders still were not tempted to attack their main force, and Saladin led his men back across the river once provisions and supplies ran low.[121] Saladin still had to exact retribution on Raynald, so he twice besieged Kerak, Raynald's fortress in Oultrejordain. The first time was in 1183, following his unsuccessful campaign into Galilee, but a relief force caused him to withdraw. He opened his campaign of 1184 with a second siege of Kerak, hoping this time to draw the Crusader army into battle on open ground, but they outmaneuvered him and successfully relieved the fortress.

Following the failure of his Kerak sieges, Saladin temporarily turned his attention back to another long-term project and resumed attacks on the territory of Izz ad-Din (Mas'ud ibn Mawdud ibn Zangi), around Mosul, which he had begun with some success in 1182. However, since then, Masʻūd had allied himself with the powerful governor of Azerbaijan and Jibal, who in 1185 began moving his troops across the Zagros Mountains, causing Saladin to hesitate in his attacks. The defenders of Mosul, when they became aware that help was on the way, increased their efforts, and Saladin subsequently fell ill, so in March 1186 a peace treaty was signed.[122] Meanwhile, Raynald retaliated for the earlier sieges of Kerak by looting a caravan of pilgrims on the Hajj during the winter of 1186–87. According to the later 13th-century Old French Continuation of William of Tyre, Raynald captured Saladin's sister in a raid on a caravan; this claim is not attested in contemporary sources, Muslim or Frankish, however, instead stating that Raynald had attacked a preceding caravan, and Saladin set guards to ensure the safety of his sister and her son, who came to no harm.[citation needed] On hearing of the attack, Saladin vowed that he would personally slay Raynald for breaking the truce, a vow he would keep.[123] The outrage also led Saladin to resolve to dispense with half-measures to rein in the unruly lord of Kerak, and to instead topple the entire edifice of the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem, thus precipitating the invasion of the summer of 1187.[123]

On 4 July 1187, Saladin faced the combined forces of Guy of Lusignan, King Consort of Jerusalem, and Raymond III of Tripoli at the Battle of Hattin. In this battle alone the Crusader force was largely annihilated by Saladin's determined army. It was a major disaster for the Crusaders and a turning point in the history of the Crusades. Saladin captured Raynald and was personally responsible for his execution in retaliation for his attacks against Muslim caravans. The members of these caravans had, in vain, besought his mercy by reciting the truce between the Muslims and the Crusaders, but Raynald ignored this and insulted the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, before murdering and torturing some of them. Upon hearing this, Saladin swore an oath to personally execute Raynald.[124] Guy of Lusignan was also captured. Seeing the execution of Raynald, he feared he would be next. However, his life was spared by Saladin, who said of Raynald, "[i]t is not the wont of kings, to kill kings; but that man had transgressed all bounds, and therefore did I treat him thus."[125][126]

Capture of Jerusalem

Saladin had captured almost every Crusader city. Saladin preferred to take Jerusalem without bloodshed and offered generous terms, but those inside refused to leave their holy city, vowing to destroy it in a fight to the death rather than see it handed over peacefully. Jerusalem capitulated to his forces on Friday, 2 October 1187, after a siege. When the siege had started, Saladin was unwilling[127] to promise terms of quarter to the Frankish inhabitants of Jerusalem. Balian of Ibelin threatened to kill every Muslim hostage, estimated at 5,000, and to destroy Islam's holy shrines of the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque if such quarter were not provided. Saladin consulted his council and the terms were accepted. The agreement was read out through the streets of Jerusalem so that everyone might within forty days provide for himself and pay to Saladin the agreed tribute for his freedom.[128] An unusually low ransom was to be paid for each Frank in the city, whether man, woman, or child, but Saladin, against the wishes of his treasurers, allowed many families who could not afford the ransom to leave.[129][130] Patriarch Heraclius of Jerusalem organised and contributed to a collection that paid the ransoms for about 18,000 of the poorer citizens, leaving another 15,000 to be enslaved. Saladin's brother al-Adil "asked Saladin for a thousand of them for his own use and then released them on the spot." Most of the foot soldiers were sold into slavery.[131] Upon the capture of Jerusalem, Saladin summoned the Jews and permitted them to resettle in the city.[132] In particular, the residents of Ascalon, a large Jewish settlement, responded to his request.

Tyre, on the coast of modern-day Lebanon, was the last major Crusader city that was not captured by Muslim forces. Strategically, it would have made more sense for Saladin to capture Tyre before Jerusalem; Saladin, however, chose to pursue Jerusalem first because of the importance of the city to Islam. Tyre was commanded by Conrad of Montferrat, who strengthened its defences and withstood two sieges by Saladin. In 1188, at Tortosa, Saladin released Guy of Lusignan and returned him to his wife Sibylla of Jerusalem. They went first to Tripoli, then to Antioch. In 1189, they sought to reclaim Tyre for their kingdom but were refused admission by Conrad, who did not recognize Guy as king. Guy then set about besieging Acre.[133]

Saladin was on friendly terms with Queen Tamar of Georgia. Saladin's biographer Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad reports that, after Saladin's conquest of Jerusalem, the Georgian Queen sent envoys to the sultan to request the return of confiscated possessions of the Georgian monasteries in Jerusalem. Saladin's response is not recorded, but the queen's efforts seem to have been successful as Jacques de Vitry, the Bishop of Acre, reports the Georgians were, in contrast to the other Christian pilgrims, allowed a free passage into the city with their banners unfurled. Ibn Šaddād furthermore claims that Queen Tamar outbid the Byzantine emperor in her efforts to obtain the relics of the True Cross, offering 200,000 gold pieces to Saladin who had taken the relics as booty at the battle of Hattin, but to no avail.[134][135]

According to Baha ad-Din, after these victories, Saladin mused of invading Europe, saying: "I think that when God grants me victory over the rest of Palestine I shall divide my territories, make a will stating my wishes, then set sail on this sea for their far-off lands in and pursue the Franks there, so as to free the earth of anyone who does not believe in God, or die in the attempt."[136]

Third Crusade

It is equally true that his generosity, his piety, devoid of fanaticism, that flower of liberality and courtesy which had been the model of our old chroniclers, won him no less popularity in Frankish Syria than in the lands of Islam.

Hattin and the fall of Jerusalem prompted the Third Crusade (1189–1192), which was partially financed by a special "Saladin tithe" in 1188. King Richard I led Guy's siege of Acre, conquered the city and executed almost 3,000 Muslim prisoners of war.[138] Baha ad-Din wrote:

The motives of this massacre are differently told; according to some, the captives were slain by way of reprisal for the death of those Christians whom the Musulmans had slain. Others again say that the king of England, on deciding to attempt the conquest of Ascalon, thought it unwise to leave so many prisoners in the town after his departure. God alone knows what the real reason was.[138]

The armies of Saladin engaged in combat with the army of King Richard at the Battle of Arsuf on 7 September 1191, at which Saladin's forces suffered heavy losses and were forced to withdraw. After the battle of Arsuf, Richard occupied Jaffa, restoring the city's fortifications. Meanwhile, Saladin moved south, where he dismantled the fortifications of Ascalon to prevent this strategically important city, which lay at the junction between Egypt and Palestine, from falling into Crusader hands.[139]

In October 1191, Richard began restoring the inland castles on the coastal plain beyond Jaffa in preparation for an advance on Jerusalem. During this period, Richard and Saladin passed envoys back and forth, negotiating the possibility of a truce.[140] Richard proposed that his sister Joan should marry Saladin's brother and that Jerusalem could be their wedding gift.[141] However, Saladin rejected this idea when Richard insisted that Saladin's brother convert to Christianity. Richard suggested that his niece Eleanor, Fair Maid of Brittany be the bride instead, an idea that Saladin also rejected.[142]

In January 1192, Richard's army occupied Beit Nuba, just twelve miles from Jerusalem, but withdrew without attacking the Holy City. Instead, Richard advanced south on Ascalon, where he restored the fortifications. In July 1192, Saladin tried to threaten Richard's command of the coast by attacking Jaffa. The city was besieged, and Saladin very nearly captured it; however, Richard arrived a few days later and defeated Saladin's army in a battle outside the city.[143]

The Battle of Jaffa (1192) proved to be the last military engagement of the Third Crusade. After Richard reoccupied Jaffa and restored its fortifications, he and Saladin again discussed terms. At last Richard agreed to demolish the fortifications of Ascalon, while Saladin agreed to recognize Crusader control of the Palestinian coast from Tyre to Jaffa. The Christians would be allowed to travel as unarmed pilgrims to Jerusalem, and Saladin's kingdom would be at peace with the Crusader states for the following three years.[144]

Death

Saladin died of a fever on 4 March 1193 (27 Safar 589 AH) at Damascus,[145] not long after King Richard's departure. In Saladin's possession at the time of his death were one piece of gold and forty pieces of silver.[146] He had given away his great wealth to his poor subjects, leaving nothing to pay for his funeral.[147] He was buried in a mausoleum in the garden outside the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, Syria. Originally the tomb was part of a complex which also included a school, Madrassah al-Aziziah, of which little remains except a few columns and an internal arch.[148] Seven centuries later, Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany donated a new marble sarcophagus to the mausoleum. However, the original sarcophagus was not replaced; instead, the mausoleum, which is open to visitors, now has two sarcophagi: the marble one placed on the side and the original wooden one, which covers Saladin's tomb.

Family

Imad ad-Din al-Isfahani compiled a list of Saladin's sons along with their dates of birth, according to information provided by Saladin late in his reign.[149] Notable members of Saladin's progeny, as listed by Imad, include:

- al-Afḍal Nur ad-Din Ali, emir of Damascus (b. 1 Shawwal 565 AH (c. 25 June 1170) in Egypt)

- al-'Azīz Imad ad-Din Abu al-Fath Uthman, sultan of Egypt (b. 8 Jumada I 567 AH (c. 14 January 1172) in Egypt)

- al-Ẓāhir Ghiyath ad-Din Abu Mansur Ghazi, emir of Aleppo (b. mid-Ramadan 568 AH (May 1173) in Egypt)

- al-Mu'aẓẓam Fakhr ad-Din Abu Mansur Turanshah, (b. Rabi I 577 AH (July/August 1181) in Egypt)

The sons listed by Imad number fifteen, but elsewhere he writes that Saladin was survived by seventeen sons and one daughter. Saladin's daughter is said to have married her cousin al-Kamil Muhammad ibn Adil. Saladin may also have had other children who died before him. One son, Al-Zahir Dawud, whom Imad listed eighth, is recorded as being Saladin's twelfth son in a letter written by his minister.[149]

Not much is known of Saladin's wives or slave-women. He married Ismat ad-Din Khatun, the widow of Nur ad-Din Zengi, in 1176. She did not have children. One of his wives, Shamsah, is buried with her son al-Aziz in the tomb of al-Shafi'i.[150]

Recognition and legacy

Muslim world

Saladin has become a prominent figure in Islamic, Arab, Turkish and Kurdish culture,[151] and he has been described as the most famous Kurd in history.[152][153][154][155] Historian ibn Munqidh mentioned him as the person who revived the reign[clarification needed] of Rashidun Caliphs. The Turkish writer Mehmet Akif Ersoy called him the most beloved sultan of the Orient.[145]

In 1898, German emperor Wilhelm II visited Saladin's tomb to pay his respects.[156] The visit, coupled with anti-imperialist sentiments, encouraged the image in the Arab world of Saladin as a hero of the struggle against the West, building on was the romantic one created by Walter Scott and other Europeans in the West at the time. Saladin's reputation had previously been largely forgotten in the Muslim world, eclipsed by more successful figures,[clarification needed] such as Baybars of Egypt.[157]

Modern Arab states have sought to commemorate Saladin through various measures, often based on the image created of him in the 19th-century west.[158] A governorate centered around Tikrit and Samarra in modern-day Iraq is named after him, as is Salahaddin University in Erbil, the largest city of Iraqi Kurdistan. A suburban community of Erbil, Masif Salahaddin, is also named after him.

Few structures associated with Saladin survive within modern cities. Saladin first fortified the Citadel of Cairo (1175–1183), which had been a domed pleasure pavilion with a fine view in more peaceful times. In Syria, even the smallest city is centred on a defensible citadel, and Saladin introduced this essential feature to Egypt.

Although the Ayyubid dynasty that he founded would outlive him by only 57 years, the legacy of Saladin within the Arab world continues to this day. With the rise of Arab nationalism in the 20th century, particularly with regard to the Arab–Israeli conflict, Saladin's heroism and leadership gained a new significance. Saladin's recapture of Palestine from the European Crusaders is considered an inspiration for modern-day Arabs' opposition to Zionism. Moreover, the glory and comparative unity of the Arab world under Saladin was seen as the perfect symbol for the new unity sought by Arab nationalists, such as Gamal Abdel Nasser. For this reason, the Eagle of Saladin became the symbol of revolutionary Egypt, and was subsequently adopted by several other Arab states (the United Arab Republic, Iraq, Libya, the State of Palestine, and Yemen).

Among Egyptian Shias, Saladin is dubbed as "Kharab ad-Din", the destroyer of religion—a derisive play on the name "Saladin."[159]

Western world

Saladin was widely renowned in medieval Europe as a model of kingship, and in particular of the courtly virtue of regal generosity. As early as 1202/03, Walther von der Vogelweide urged the German King Philip of Swabia to be more like Saladin, who believed that a king's hands should have holes to let the gold fall through.[c] By the 1270s, Jans der Enikel was spreading the fictitious but approving story of Saladin's table,[d] which presented him as both pious and wise to religious diversity.[161] In The Divine Comedy (1308–1320), Dante mentions him as one of the virtuous non-Christians in limbo,[162] and he is also depicted favorably in Boccaccio's The Decameron (1438–53).[163]

Although Saladin faded into history after the Middle Ages, he appears in a sympathetic light in modern literature, first in Lessing's play Nathan the Wise (1779), which transfers the central idea of "Saladin's table" to the post-medieval world. He is a central character in Sir Walter Scott's novel The Talisman (1825), which more than any other single text influenced the romantic view of Saladin. Scott presented Saladin as a "modern [19th-century] liberal European gentlemen, beside whom medieval Westerners would always have made a poor showing".[164] 20th-century French author Albert Champdor described him as "Le plus pur héros de l'Islam" (English: The purest Hero of Islam).[165] Despite the Crusaders' slaughter when they originally conquered Jerusalem in 1099, Saladin granted amnesty and free passage to all common Catholics and even to the defeated Christian army, as long as they were able to pay the aforementioned ransom (the Greek Orthodox Christians were treated even better because they often opposed the western Crusaders).[citation needed]

Notwithstanding the differences in beliefs, the Muslim Saladin was respected by Christian lords, Richard especially. Richard once praised Saladin as a great prince, saying that he was, without doubt, the greatest and most powerful leader in the Islamic world.[166] Saladin, in turn, stated that there was not a more honorable Christian lord than Richard. After the treaty, Saladin and Richard sent each other many gifts as tokens of respect but never met face to face. In April 1191, a Frankish woman's three-month-old baby had been stolen from her camp and sold on the market. The Franks urged her to approach Saladin herself with her grievance. According to Ibn Shaddad, Saladin used his own money to buy the child back:

He gave it to the mother and she took it; with tears streaming down her face, and hugged the baby to her chest. The people were watching her and weeping and I (Ibn Shaddad) was standing amongst them. She suckled it for some time and then Saladin ordered a horse to be fetched for her and she went back to camp.[167][168]

Mark Cartwright, the publishing director of World History Encyclopedia, writes: "Indeed, it is somewhat ironic that the Muslim leader became one of the great exemplars of chivalry in 13th century European literature. Much has been written about the sultan during his own lifetime and since, but the fact that an appreciation for his diplomacy and leadership skills can be found in both contemporary Muslim and Christian sources would suggest that Saladin is indeed worthy of his position as one of the great medieval leaders."[169]

Cultural depictions of Saladin

Novels

- The Talisman by Walter Scott. Published in 1825 it is set during the Third Crusade and centres on the relationship between Richard I of England and Saladin.

- The Crusades trilogy (1998–2000) by Jan Guillou is about a young nobleman from present-day Sweden who is exiled and forced to participate in the Crusades in the Middle East. In it he comes across Saladin who in the story has the role of a "helper."

- The Book of Saladin (1998) by Tariq Ali, a novel based on Saladin's life.[170]

Film, television and animation

- Ghazi Salahuddin, a 1939 Indian drama film by I. A. Hafesjee. The first depiction of Saladin on film, it stars Ghulam Mohammed as the sultan, Ratan Bai as Rihana, Mazhar Khan as Richard, Lalita Devi as Isabella, Mohammed Ishaq as Saifuddin, Yakub as Conrad, Ishwarlal as Nooruddin, W.M. Khan as Humphrey, Bhupatrai as Frederick, and Mirza Musharraf as Yanoos.[171][172][173]

- Saladin the Victorious – a 1963 Egyptian war drama film. Ahmed Mazhar as Saladin, Salah Zulfikar as Issa Al Awwam and Hamdy Gheith as Richard.

- Doctor Who – Saladin is portrayed by Bernard Kay in the 1965 serial "The Crusade" opposite Julian Glover as Richard the Lionheart along with series regulars William Hartnell, William Russell, Jacqueline Hill and Maureen O'Brien as The First Doctor, Ian Chesterton, Barbara Wright and Vicki, respectively.

- Kingdom of Heaven – Saladin's role was played by Ghassan Massoud.

- King Richard and the Crusaders – Saladin's role was played by Rex Harrison.

- Salah ad-Deen Al-Ayyobi – a 2001 TV series on Salah ad-Din's life.

- Saladin: The Animated Series – an animated project inspired by the life of Salah ad-Din.

- Kudüs Fatihi Selahaddin Eyyubi – Salahuddin al-Ayyubi is portrayed in Turkish TV series by Uğur Güneş.

- Arn: The Knight Templar – Saladin's role was played by Milind Soman.

Video games

- Saladin appears as the leader of the Arabian civilization in several installments of Sid Meier's Civilization video game series.[174][175] He also appears as the leader of the Ayyubids in the "Into the Renaissance" scenario from the Gods & Kings expansion for Civilization V.[176]

- Saladin is a playable character in the Mobile/PC Game Rise of Kingdoms.

- The popular real-time strategy video game Age of Empires II: The Age of Kings features a campaign based on the exploits of Saladin.

Visual art

- The Statue of Saladin is an oversize equestrian bronze statue depicting Saladin located in front of the 11th century Citadel of Damascus in the Ancient City of Damascus in Damascus, Syria.

See also

- Battles of Saladin

- List of Ayyubid rulers

- List of Kurdish dynasties and countries

- Sharaf Khan Bidlisi

- Libellus de expugnatione Terrae Sanctae per Saladinum

- Kingdom of Heaven

- King Richard and the Crusaders

- Saladin: The Animated Series

- Saladin the Victorious

- Salah ad-Din (TV series)

- Kufranjah City

- Arn – The Knight Templar

Notes

- ^ Arabic: صلاح الدين يوسف بن أيوب / ALA-LC: Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsuf ibn Ayyūb; full name: al-Malik al-Nāṣir Abūʾl-Muẓaffar Yūsūf ibn Ayyūb[4]

- ^ /ˈsælədɪn/. 'Saladin' is a contraction of an honorific laqab, from the Arabic: صلاح الدین, romanized: Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn, lit. 'Honour of the Faith'.[5]

- ^ Denk an den milten Salatîn / der jach, daz küniges hende dürkel solten sîn / sô wurden sî erforht und ouch geminnet. (Think of the generous Saladin, who said that kings' hands should have holes, that they might be both feared and loved.)[160]

- ^ Saladin had a table that was made of a gigantic sapphire. As the end of his life approached, he wanted to dedicate the table to God in the hope of eternal life, but he couldn't decide which god to honour, the Muslim God, the Christian or the Jewish, as there was no way to tell which was most powerful. So he had the table cut in three parts and gifted each of them a third of it (Jans, Weltchronik, 26551–26675).[161]

References

- ^ a b c Nicolle 2011, p. 26: "This copper dirham, minted at Mayyafariqin in 587 AH (1190/01 AD) shows Saladin wearing the sharbush hat of a Saljuq-style Turkish ruler."

- ^ a b Lesley Baker, Patricia (1988). A History of Islamic Court Dress in the Middle East (PDF) (phd). SOAS, London University. p. 119. doi:10.25501/SOAS.00033676.

By the end of the 12th century, the wearing of the sharbush demonstrated support for Salah al-Din. Under the later Bahri Mamluks of Egypt and Syria it formed part of the khil'a given to an amir on his investiture.

- ^ a b c d Balog (1980). The Coinage of the Ayyubids. London: Royal Numismatic Society. p. Coin 182., also Whelan Type III, 258-60; Album 791.4

- ^ Richards 1995, p. 910.

- ^ Lane-Poole 1906, p. 6.

- ^ a b Morton, Nicholas (2020). The Crusader States and Their Neighbours: A Military History, 1099–1187. Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-19-882454-1.

- ^ H. A. R. Gibb, "The Rise of Saladin", in A History of the Crusades, vol. 1: The First Hundred Years, ed. Kenneth M. Setton (University of Wisconsin Press, 1969). p. 563.

- ^ The medieval historian Ibn Athir relates a passage from another commander: "...both you and Saladin are Kurds and you will not let power pass into the hands of the Turks." Minorsky (1957): [page needed]

- ^ a b Lane-Poole 1906, p. 4.

- ^ The biographer Ibn Khallikan wrote, "Historians agree in stating that [Saladin's] father and family belonged to Duwin. ... They were Kurds and belonged to the Rawādiya [sic], which is a branch of the great tribe al-Hadāniya": Minorsky (1953), p. 124.

- ^ Humphreys, R. Stephen (1977). From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus, 1193–1260. State University of New York Press. p. 29. ISBN 0-87395-263-4.

Among the free-born amirs the Kurds would seem the most dependent on Saladin's success for the progress of their own fortunes. He too was a Kurd, after all ...

- ^ "Saladin". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 April 2023.

Saladin was born into a prominent Kurdish family.

- ^ Baha ad-Din 2002, p. 17.

- ^ Ter-Ghevondyan 1965, p. 218.

- ^ Tabbaa 1997, p. 31.

- ^ 'Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani (20 January 2019). Jamal ad-Din Faleh al-Kilani [in Arabic] (ed.). "Futuh al-Ghayb ("Revelations of the Unseen")". Google Books (in Arabic).

وقد تأثر به القائد صلاح الدين الأيوبي، والشيخ معين الدين الجشتي، والشيخ شهاب الدين عمر السهروردي رحمهم الله

- ^ Azzam, Abdul Rahman (2009). Saladin. Pearson Longman. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-4058-0736-4.

- ^ a b Lyons & Jackson 1982, p. 3.

- ^ Eddé 2011.

- ^ a b Lyons & Jackson 1982.

- ^ a b "Who2 Biography: Saladin, Sultan / Military Leader". Answers.com. Retrieved 20 August 2008.

- ^ Chase 1998, p. 809.

- ^ Şeşen 2009, p. 440.

- ^ "acsearch.info - Auction research". www.acsearch.info. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ "Copper alloy dirham of Saladin, Nisibin, 578 H." numismatics.org. American Numismatic Society.

- ^ a b c d e Caldwell Ames, Christine (2015). Medieval Heresies. Cambridge University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-1107023369.

- ^ Michael Haag (2012). The Tragedy of the Templars: The Rise and Fall of the Crusader States. Profile Books. p. 158. ISBN 978-1847658548.

As an orthodox but esoteric alternative to Ismailism, Saladin encouraged Sufism and built khanqahs—that is, Sufi hostels—and he also introduced madrasas, theological colleges that promoted the acceptable version of the faith. Numerous khanqahs and madrasas were built throughout Cairo and Egypt in Saladin's effort to combat and suppress what he regarded as the Ismaili heresy.

- ^ Arab Historians of the Crusades. University of California Press. 1984. pp. 99–100. ISBN 9780520052246.

- ^ J. Spencer Trimingham (1998). The Sufi Orders in Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0198028239.

- ^ Nathan Hofer (2015). The Popularisation of Sufism in Ayyubid and Mamluk Egypt, 1173–1325. Edinburgh University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0748694228.

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (2024). "Chapter 12: Mamluk Dress between Text and Image". Dress and Dress Code in Medieval Cairo: A Mamluk Obsession. pp. 172–173. doi:10.1163/9789004684980_013. ISBN 9789004684980.

- ^ Contadini, Anna (1998). Poetry on Enamelled Glass: The Palmer Cup in the British Museum.' In: Ward, R, (ed.), Gilded and Enamelled Glass from the Middle East. British Museum Press. pp. 58–59.

- ^ Contadini, Anna (2017). Text and Image on Middle Eastern Objects: The Palmer Cup in Context (in A Rothschild Renaissance: A New Look at the Waddesdon Bequest in the British Museum). British Museum Research Publications. p. 130.