Raifuku Maru

Raifuku Maru | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Raifuku Maru |

| Owner | Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, Ltd.[1] |

| Port of registry | Kobe, Japan |

| Builder | Kawasaki Dockyard, Kobe |

| Yard number | 427 |

| Completed | November 1918 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | foundered in a storm[2] |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage | 5,867 GRT; 4,259 NRT[1] |

| Length | 385.0 ft (117.3 m)[1] |

| Beam | 151.0 ft (46.0 m) |

| Depth | 36.0 ft (11.0 m)[3] |

| Decks | 2 |

| Installed power | 1 × triple-expansion engine; 440 NHP[1] |

| Propulsion | 1 × screw |

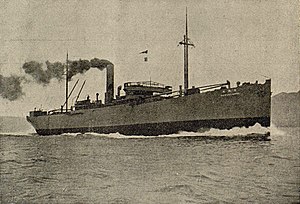

The SS Raifuku Maru (来福丸 (Kyūjitai: 來福丸), Raifuku Maru) was a Japanese Dai-ichi Taifuku Maru-class cargo ship, which was built in 1918 at Kawasaki Dockyard in Kobe, Japan, and owned by Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, Ltd. On 21 April 1925, it sank in a heavy storm during a voyage from Boston, USA, to Hamburg, Germany, with a cargo of wheat and a crew of 38, all of whom were lost.[2][3]

Loss

The Raifuku Maru left Boston on 18 April 1925. On 21 April, she sailed into a heavy storm, and the cargo of wheat began to shift, causing the ship to take on an increasing list to one side.[2] The White Star Liner RMS Homeric and several other ships received the following signal from the Japanese ship's wireless telegraphist, Masao Hiwatari: "Now very danger! Come quick!" Despite the broken English of the Japanese crewmen, it was clear that the ship was in trouble. Homeric, and the British ship King Alexander, tried to reach Raifuku Maru, but was unable to get close enough to rescue any crew due to the rough seas. The ship listed at a 30-degree angle, and sank with all hands as Homeric's crew and passengers watched.[2] Homeric sent the following message to the Camperdown Signal Station: "OBSERVED STEAMER RAIFUKU MARU SINK IN LAT 4143N LONG 6139W REGRET UNABLE TO SAVE ANY LIVES." Several ships tried to find bodies or survivors from the ship in the days after the sinking, but found none.[3]

The incident was controversial at the time; when Homeric arrived in New York, several of the passengers publicly accused the crew of Homeric of not making enough effort to save Raifuku Maru's crew. This was taken up by the Japanese government, who accused the English captains of racism for not saving their crewmen. However this was strenuously denied by Homeric's crew and White Star Line, who argued that they had made every effort to rescue the crew.[2][3]

Myths and legends

Several early reports of the incident, including those of the Associated Press, claimed that Hiwatari sent a frantic message reading "Danger like dagger now!"[4] The source of this quote is unknown, since it isn't included in radio logs or official records of the incident, but appears in many early accounts of Raifuku Maru's sinking.[5] Divorced of its original context, the "dagger" comment became the basis for a popular legend that the ship disappeared without a trace after sending the message.[6] Later writers speculated over what the "dagger" was (with waterspouts and UFOs frequently blamed),[2] and the incident became remembered as a genuine mystery of the sea. Popular writers on the Bermuda Triangle, specifically Charles Berlitz[2] and Richard Winer, propagated the myth of the ship's "mysterious" sinking.[citation needed]

Newspaper sources

- "Japanese Ships Sinks With A Crew Of 38; Liners Unable To Aid" The New York Times, April 22, 1925.

- "Passengers Differ On Homeric Effort To Save Sinking Ship" The New York Times, April 23, 1925.

- "Homeric Captain Upheld By Skippers" The New York Times, April 24, 1925.

- "Liner Is Battered In Rescue Attempt" The New York Times, April 25, 1925.

References

- ^ a b c d www.wrecksite.eu - (Note: this website states that the crew was 48, whereas most other sources say 38)

- ^ a b c d e f g Jay Sivell. Wordpress.com

- ^ a b c d G. Roscoe Spurgeon "Radio Stations Common? Not This Kind" coastalradio.co.uk

- ^ "Danger like dagger". Logansport Pharos-Tribune.

- ^ Christopher Saunders, "Things That Are Not: The Raifuku Maru, from Tragedy to Myth". The Avocado, 13 October 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ Charles Berlitz, The Bermuda Triangle (1974), p. 54