RMS Olympic

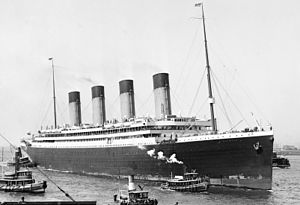

RMS Olympic arriving at New York on her maiden voyage, 21 June 1911 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | RMS Olympic |

| Owner |

|

| Operator |

|

| Port of registry | Liverpool |

| Route | Southampton – Cherbourg – Queenstown – New York City |

| Ordered | 1907 |

| Builder | Harland & Wolff, Belfast |

| Cost | $7.5 million (USD) |

| Yard number | 400 |

| Way number | 347 |

| Laid down | 16 December 1908 |

| Launched | 20 October 1910 |

| Completed | 31 May 1911 |

| Maiden voyage | 14 June 1911 |

| In service | 1911–1935 |

| Out of service | 12 April 1935 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Scrapped 1935–37 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Olympic-class ocean liner |

| Tonnage | 45,324 gross register tons; 46,358 after 1913; 46,439 after 1920 |

| Displacement | 52,067 tons |

| Length | 882 ft 9 in (269.1 m)[1] |

| Beam | 92 ft 9 in (28.3 m) |

| Height | 175 ft (53.4 m) (keel to top of funnels) |

| Draught | 34 ft 7 in (10.5 m) |

| Decks | 9 decks (8 for passengers and 1 for crew) |

| Installed power | 24 double-ended (six furnace) and 5 single-ended (three furnace) Scotch boilers originally coal burning, later converted to oil fired in 1919. Two four-cylinder triple-expansion reciprocating engines each producing 15,000 hp for the two outboard wing propellers at 85 revolutions per minute. One low-pressure turbine producing 16,000 hp. Total 46,000 hp,[2] however capable of 59,000 hp at full speed.[3] |

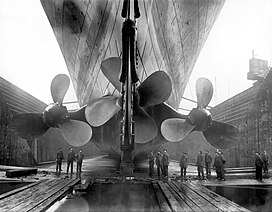

| Propulsion | Two bronze three-bladed wing propellers. One bronze four-bladed centre propeller. |

| Speed | |

| Capacity | 2,435 passengers |

| Crew | 950 |

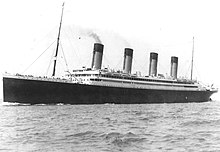

RMS Olympic was a British ocean liner and the lead ship of the White Star Line's trio of Olympic-class liners. Olympic had a career spanning 24 years from 1911 to 1935, in contrast to her short-lived sister ships, Titanic and Britannic. This included service as a troopship during the First World War, which gained her the nickname "Old Reliable", and during which she rammed and sank the U-boat U-103. She returned to civilian service after the war, and served successfully as an ocean liner throughout the 1920s and into the first half of the 1930s, although increased competition, and the slump in trade during the Great Depression after 1930, made her operation increasingly unprofitable. Olympic was withdrawn from service and sold for scrap on 12 April 1935, which was completed in 1937.

Olympic was the largest ocean liner in the world for two periods during 1910–13, interrupted only by the brief tenure of the slightly larger Titanic, which had the same dimensions but higher gross register tonnage, before the German SS Imperator went into service in June 1913. Olympic also held the title of the largest British-built liner until RMS Queen Mary was launched in 1934, interrupted only by the short careers of Titanic and Britannic.[5][6] The other two ships in the class had short service lives: in 1912, Titanic collided with an iceberg on her maiden voyage and sank in the North Atlantic; Britannic never operated in her intended role as a passenger ship, instead serving as a hospital ship during the First World War until she hit a mine and sank in the Aegean Sea in 1916.

Background and construction

Built in Belfast, Ireland,[7] Olympic was the first of the three Olympic-class ocean liners – the others being Titanic and Britannic.[8] They were the largest vessels built for the British shipping company White Star Line, which was a fleet of 29 steamers and tenders in 1912.[9] The three ships had their genesis in a discussion in mid-1907 between the White Star Line's chairman, J. Bruce Ismay, and the American financier J. Pierpont Morgan, who controlled the White Star Line's parent corporation, the International Mercantile Marine Co. The White Star Line faced a growing challenge from its main rivals Cunard, which had just launched Lusitania and Mauretania – the fastest passenger ships then in service – and the German lines Hamburg America and Norddeutscher Lloyd.[10] Ismay preferred to compete on size and economics rather than speed and proposed to commission a new class of liners that would be bigger than anything that had gone before as well as being the last word in comfort and luxury. The company sought an upgrade in their fleet primarily in response to the largest Cunarders but also to replace their largest and now outclassed ships from 1890, RMS Teutonic and RMS Majestic. The former was replaced by Olympic while Majestic was replaced by Titanic. Majestic would be brought back into her old spot on White Star's New York service after Titanic's loss.

The ships were built in Belfast by Harland & Wolff, who had a long-established relationship with the White Star Line dating back to 1867.[11] Harland and Wolff were given a great deal of latitude in designing ships for the White Star Line; the usual approach was for the latter to sketch out a general concept which the former would take away and turn into a ship design. Cost considerations were relatively low on the agenda and Harland and Wolff was authorised to spend what it needed on the ships, plus a five per cent profit margin.[12] In the case of the Olympic-class ships, a cost of £3 million for the first two ships was agreed plus "extras to contract" and the usual five per cent fee.[13]

Harland and Wolff put their designers to work designing the Olympic-class vessels. It was overseen by Lord Pirrie, a director of both Harland and Wolff and the White Star Line; naval architect Thomas Andrews, the managing director of Harland and Wolff's design department; Edward Wilding, Andrews' deputy and responsible for calculating the ship's design, stability and trim; and Alexander Carlisle, the shipyard's chief draughtsman and general manager.[14] Carlisle's responsibilities included the decorations, equipment and all general arrangements, including the implementation of an efficient lifeboat davit design.[15][16]

On 29 July 1908, Harland and Wolff presented the drawings to Bruce Ismay and other White Star Line executives. Ismay approved the design and signed three "letters of agreement" two days later authorising the start of construction.[17] At this point the lead ship – which was later to become Olympic – had no name, but was referred to simply as "Number 400", as it was Harland and Wolff's four hundredth hull. Titanic was based on a revised version of the same design and was given the number 401.[18] Bruce Ismay's father Thomas Henry Ismay had previously planned to build a ship named Olympic as a sister ship to Oceanic. The senior Ismay died in 1899 and the order for the ship was cancelled.[19]

Construction of Olympic began three months before Titanic to ease pressures on the shipyard. Several years would pass before Britannic would be launched. To accommodate the construction of the class, Harland and Wolff upgraded their facility in Belfast; the most dramatic change was the combining of three slipways into two larger ones. Olympic and Titanic were constructed side by side.[16] Olympic's keel was laid on 16 December 1908 and she was launched on 20 October 1910, without having been christened beforehand.[8] By tradition, the White Star Line never christened any of their vessels and for the launch the hull was painted in a light grey colour for photographic purposes; a common practice of the day for the first ship in a new class, as it made the lines of the ship clearer in the black-and-white photographs.[20] The launch was filmed both in black and white and in Kinemacolor, with only the black and white footage surviving.[21][22] The launches of Titanic and Britannic were also filmed, though only Britannic's survived.[23] Her hull was repainted black following the launch.[6] The ship was then dry-docked for fitting out.

Olympic was driven by three propellers. The two three-bladed wing propellers were driven by two triple-expansion engines, while the four-bladed central propeller was driven by a turbine that used recovered steam escaping from the triple-expansion engines.[24] The use of escaped steam was tested on the SS Laurentic two years earlier.[25]

Lifeboats

Olympic's lifeboat arrangement in 1911–12 was identical to Titanic's – fourteen regulation boats, two emergency cutters and the White Star complement of four collapsible boats.[26] Two collapsibles were stored (collapsible C and D) broken down under the lead boats on the port and starboard sides. The final two collapsibles were stored on the top of the officers' quarters on either side of the number one funnel. Collapsible lifeboat B was stored on the port side roof of the officers quarters and collapsible lifeboat A was on the starboard side on the roof of the officers quarters.

Features

Olympic was designed as a luxury ship; Titanic's passenger facilities, fittings, deck plans and technical facilities were largely identical to Olympic, although with some small variations.[27] The first-class passengers enjoyed luxurious cabins, and some were equipped with private bathrooms. First-class passengers could have meals in the ship's large and luxurious dining saloon or in the more intimate A La Carte Restaurant. There was a lavish Grand Staircase, built only for the Olympic-class ships, along with three lifts that ran behind the staircase down to E deck,[28] a Georgian-style smoking room, a Veranda Café decorated with palm trees,[29] a swimming pool, Victorian Turkish bath,[30] gymnasium,[31] and several other places for meals and entertainment.

The second-class facilities included a smoking room, a library, a spacious dining room, and a lift.[6][32]

Finally, the third-class passengers enjoyed reasonable accommodation compared to other ships. Instead of large dormitories offered by most ships of the time, the third-class passengers of Olympic travelled in cabins containing two to ten bunks. Facilities for the third class included a smoking room, a common area, and a dining room.[6][32]

Olympic had a cleaner, sleeker look than other ships of the day: rather than fitting her with bulky exterior air vents, Harland and Wolff used smaller air vents with electric fans, with a "dummy" fourth funnel used for additional ventilation. For the power plant Harland and Wolff employed a combination of reciprocating engines with a centre low-pressure turbine, as opposed to the steam turbines used on Cunard's Lusitania and Mauretania.[33] White Star had successfully tested this engine configuration on the earlier liner SS Laurentic, where it was found to be more economical than expansion engines or turbines alone. Olympic consumed 650 tons of coal per 24 hours with an average speed of 21.7 knots on her maiden voyage, compared to 1,000 tons of coal per 24 hours for both Lusitania and Mauretania.[34]

Differences from Titanic

The Olympic and Titanic were nearly identical, and were based on the same core design. A few alterations were made to Titanic and later on Britannic which were based on experience gained from Olympic's first year in service. The most noticeable of these was that the forward half of Titanic's A Deck promenade was enclosed by a steel screen with sliding windows, to provide additional shelter, whereas Olympic's promenade deck remained open along its whole length. The additional enclosed volume was a major contributor to Titanic's increased gross register tonnage of 46,328 tons over Olympic's 45,324 tons, which allowed Titanic to claim the title of largest ship in the world.[35]

Additionally, the B-Deck First-Class promenade decks installed on Olympic had proven to be scarcely used because of the already ample promenade space on A-Deck. Accordingly, Thomas Andrews eliminated this feature on Titanic and built additional, enlarged staterooms with en-suite bathrooms. It also allowed a Café Parisien in the style of a French sidewalk café to be added as an annexe to the À la Carte Restaurant, and for the Restaurant itself to be expanded to the Port-side of the ship. One drawback of this was that the Second-Class promenade space on B-Deck was reduced aboard Titanic.

A reception area for the restaurant was added in the foyer of the B-Deck aft Grand Staircase on Titanic, which did not exist on Olympic, and the main reception room on D-Deck was also slightly enlarged. 50-foot (15 m) private promenade decks were added to the two luxury parlour suites on B-Deck on Titanic, as well as additional First-Class gangway entrances on B-Deck. Cosmetic differences also existed between the two ships, most noticeably concerning the wider use of Axminster carpeting in Titanic's public rooms, as opposed to the more durable linoleum flooring on Olympic.

Most of these shortcomings on Olympic would be addressed in her 1913 refit, which altered the configuration of Olympic's First-Class sections to be more like those of Titanic. Although the A-Deck Promenade remained open for the entirety of Olympic's career, the B-Deck promenade was vetoed and staterooms added like those on Titanic, as well as a Café Parisien and enlarged restaurant. The 1913 refit also included modifications for greater safety after the loss of the Titanic, including the addition of extra lifeboats and the addition of an inner watertight skin in the hull along about half the length of the ship. An extra watertight compartment was added bringing the total of watertight compartments to 17. Five watertight bulkheads were raised to B deck. Along with these improvements there were many others included in the 1913 refit.[36]

Career

Following completion, Olympic started her sea trials on 29 May 1911 during which her manoeuvrability, compass, and wireless telegraphy were tested. No speed test was carried out.[37] She completed her sea trial successfully. Olympic then left Belfast bound for Liverpool, her port of registration, on 31 May 1911. As a publicity stunt the White Star Line timed the start of this first voyage to coincide with the launch of Titanic. After spending a day in Liverpool, open to the public, Olympic sailed to Southampton, where she arrived on 3 June, to be made ready for her maiden voyage.[38][39][40] Her arrival generated enthusiasm from her crew and newspapers.[41] The deep-water dock at Southampton, then known as the "White Star Dock" had been specially constructed to accommodate the new Olympic-class liners, and had opened in 1911.[42]

Her maiden voyage commenced on 14 June 1911 from Southampton, calling at Cherbourg and Queenstown, and reaching New York City on 21 June, with 1,313 passengers on board (489 first class, 263 second class and 561 third class).[43] The maiden voyage was captained by Edward Smith who would perish the following year in the Titanic disaster.[44] Designer Thomas Andrews was present for the passage to New York and return, along with a number of engineers with Bruce Ismay and Harland and Wolff's "Guarantee Group" who were also aboard for them to spot any problems or areas for improvement.[45] Andrews would also lose his life in the Titanic disaster.[46]

As the largest ship in the world, and the first in a new class of superliners, Olympic's maiden voyage attracted considerable worldwide attention from the press and public. Following her arrival in New York, Olympic was opened up to the public and received over 8,000 visitors. More than 10,000 spectators watched her depart from New York harbour, for her first return trip. There were 2,301 passengers on board for the return voyage (731 first class, 495 second class and 1,075 third class).[47] During her third crossing, an observer of the Cunard Line was on board, in search of ideas for their new ship then under construction, the Aquitania.[48]

Hawke collision

Olympic's first major mishap occurred on her fifth voyage on 20 September 1911, when she collided with the British cruiser HMS Hawke.[49] The collision took place as Olympic and Hawke were running parallel to each other through the Solent. As Olympic turned to starboard, the wide radius of her turn took the commander of Hawke by surprise, and he was unable to take sufficient avoiding action.[50] Hawke's bow, which had been designed to sink ships by ramming them, collided with Olympic's starboard side near the stern,[51] tearing two large holes in Olympic's hull, above and below the waterline, resulting in the flooding of two of her watertight compartments and a twisted propeller shaft. Olympic settled slightly by the stern,[52] but in spite of the damage was able to return to Southampton under her own power; no one was killed or seriously injured. HMS Hawke suffered severe damage to her bow and nearly capsized;[27][53] Hawke was repaired, but sunk by the German U-boat SM U-9 in October 1914.

Captain Edward Smith was in command of Olympic at the time of the incident. Two crew members, stewardess Violet Jessop and stoker Arthur John Priest,[54] survived not only the collision with Hawke but also the later sinking of Titanic and the 1916 sinking of Britannic, the third ship of the class.[55][56]

At the subsequent inquiry the Royal Navy blamed Olympic for the incident, alleging that her large displacement generated a suction that pulled Hawke into her side.[57][58] The Hawke incident was a financial disaster for Olympic's operator. A legal argument ensued which decided that the blame for the incident lay with Olympic and, although the ship was technically under the control of the harbour pilot, the White Star Line was faced with large legal bills and the cost of repairing the ship, and keeping her out of revenue service made matters worse.[50][59][60] However, the fact that Olympic endured such a serious collision and stayed afloat appeared to vindicate the design of the Olympic-class liners, and reinforced their "unsinkable" reputation.[50]

It took two weeks for the damage to Olympic to be patched up sufficiently to allow her to return to Belfast for permanent repairs, which took just over six weeks to complete.[61] To expedite repairs, Harland and Wolff was obliged to replace Olympic's damaged propeller shaft with one from Titanic, delaying the latter's completion.[62] By 20 November 1911 Olympic was back in service, but, on 24 February 1912, suffered another setback when she lost a propeller blade on an eastbound voyage from New York, and once again returned to her builder for repairs. To return her to service as soon as possible, Harland & Wolff again had to pull resources from Titanic, delaying her maiden voyage by three weeks, from 20 March to 10 April 1912.[61][63]

Titanic disaster

On 14 April 1912, Olympic, now under the command of Herbert James Haddock, was on a return trip from New York. Wireless operator Ernest James Moore[64] received the distress call from Titanic, when she was approximately 505 miles west by south of Titanic's location.[65] Haddock calculated a new course, ordered the ship's engines to be set to full power and headed to assist in the rescue.[66]

When Olympic was about 100 nautical miles (190 km; 120 mi) away from Titanic's last known position, she received a message from Captain Rostron of Cunard's RMS Carpathia, which had arrived at the scene. Rostron explained that Olympic continuing on course to Titanic would gain nothing, as "All boats accounted for. About 675 souls saved [...] Titanic foundered about 2:20 am."[65] Rostron requested that the message be forwarded to White Star and Cunard. He said that he was returning to harbour in New York.[65] Subsequently, the wireless room aboard Olympic operated as a clearing room for radio messages.[65]

When Olympic offered to take on the survivors, she was turned down by Rostron under order from Ismay,[67] who was concerned that asking the survivors to board a virtual mirror-image of Titanic would cause them distress.[68] Olympic then resumed her voyage to Southampton, with all concerts cancelled as a mark of respect, arriving on 21 April.[6][69]

Over the next few months, Olympic assisted with both the American and British inquiries into the disaster. Deputations from both inquiries inspected Olympic's lifeboats, watertight doors and bulkheads and other equipment which were identical to those on Titanic.[70] Sea tests were performed for the British enquiry in May 1912, to establish how quickly the ship could turn two points at various speeds, to approximate how long it would have taken Titanic to turn after the iceberg was sighted.[71][72]

1912 strike

Olympic, like Titanic, did not carry enough lifeboats for everyone on board, and so was hurriedly equipped with additional, second-hand collapsible lifeboats following her return to Britain.[69] Towards the end of April 1912, as she was about to sail from Southampton to New York, 284 of the ship's firemen went on strike, for fear that the ship's new collapsible lifeboats were not seaworthy.[73][74] 100 non-union crew were hastily hired from Southampton as replacements, with more being hired from Liverpool.[75]

The 40 collapsible lifeboats were transferred from troopships and put on Olympic, and many were rotten and would not open. The crewmen, instead, sent a request to the Southampton manager of the White Star Line that the collapsible boats be replaced by wooden lifeboats; the manager replied that this was impossible and that the collapsible boats had been passed as seaworthy by a Board of Trade inspector. The men were not satisfied and ceased work in protest.[74]

On 25 April, a deputation of strikers witnessed a test of four of the collapsible boats. One was unseaworthy and the deputation said that it was prepared to recommend the men return to work if the boats were replaced. However, the strikers now objected to the non-union strikebreaker crew which had come on board, and demanded that they be dismissed, which the White Star Line refused. Fifty-four sailors then left the ship, objecting to the non-union crew who they claimed were unqualified and therefore dangerous, and refused to sail with them. This led to the scheduled sailing being cancelled.[75][76]

All 54 sailors were arrested on a charge of mutiny when they went ashore. On 4 May 1912, Portsmouth magistrates found the charges against the mutineers were proven, but discharged them without imprisonment or fine, due to the special circumstances of the case.[77] Fearing that public opinion would be on the side of the strikers, the White Star Line let them return to work and Olympic sailed on 15 May.[71]

Post-Titanic refit

On 9 October 1912, White Star withdrew Olympic from service and returned her to her builders at Belfast to have modifications added to incorporate lessons learned from the Titanic disaster six months prior, and improve safety.[78] The number of lifeboats carried by Olympic was increased from twenty to sixty-eight, and extra davits were installed along the boat deck to accommodate them. An inner watertight skin was also constructed in the boiler and engine rooms, which created a double hull.[79] Five of the watertight bulkheads were extended up to B-Deck, extending to the entire height of the hull. This corrected a flaw in the original design, in which the bulkheads only rose up as far as E or D-Deck, a short distance above the waterline.[80] This flaw had been exposed during Titanic's sinking, where water spilled over the top of the bulkheads as the ship sank and flooded subsequent compartments. In addition, an extra bulkhead was added to subdivide the electrical dynamo room, bringing the total number of watertight compartments to seventeen. Improvements were also made to the ship's pumping apparatus. These modifications meant that Olympic could survive a collision similar to that of Titanic, in that her first six compartments could be breached and the ship could remain afloat.[81][82]

At the same time, Olympic's B Deck underwent a refit, which included extra cabins in place of the covered promenade, more private bathing facilities, an enlarged Á La Carte restaurant, and a Café Parisien (another addition that had proved popular on Titanic) was added, offering another dining option to first class passengers. With these changes (and a second refit in 1919 after the war), Olympic's gross register tonnage rose to 46,439 tons, 111 tons more than Titanic's.[83][84]

In March 1913, Olympic returned to service and briefly regained the title of largest ocean liner in the world, until the German liner SS Imperator entered passenger service in June 1913. Following her refit, Olympic was marketed as the "new" Olympic and her improved safety features were featured prominently in advertisements.[85][6] The ship experienced a short period of tranquility despite a storm in 1914 that broke some of the First Class windows and injured some passengers.[86]

First World War

On 4 August 1914, Britain entered the First World War. Olympic initially remained in commercial service under Captain Herbert James Haddock. As a wartime measure, Olympic was painted in a grey colour scheme, portholes were blocked, and lights on deck were turned off to make the ship less visible. The schedule was hastily altered to terminate at Liverpool rather than Southampton, and this was later altered again to Glasgow.[6][87]

The first few wartime voyages were packed with Americans trapped in Europe, eager to return home; the eastbound journeys carried few passengers. By mid-October, bookings had fallen sharply as the threat from German U-boats became increasingly serious, and White Star Line decided to withdraw Olympic from commercial service. On 21 October 1914, she left New York for Glasgow on her last commercial voyage of the war, though carrying only 153 passengers.[88][87]

Audacious incident 1914

On the sixth day of her voyage, 27 October, as Olympic passed near Lough Swilly off the north coast of Ireland, she received distress signals from the battleship HMS Audacious, which had struck a mine off Tory Island and was taking on water.[89] HMS Liverpool was in the company of Audacious.

Olympic took off 250 of Audacious's crew, then the destroyer HMS Fury managed to attach a tow cable between Audacious and Olympic and they headed west for Lough Swilly. However, the cable parted after Audacious's steering gear failed. A second attempt was made to tow the warship, but the cable became tangled in HMS Liverpool's propellers and was severed. A third attempt was tried but also failed when the cable gave way. By 17:00 the Audacious's quarterdeck was awash and it was decided to evacuate the remaining crew members to Olympic and Liverpool, and at 20:55 there was an explosion aboard Audacious and she sank.[90]

Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, Commander of the Home Fleet, was anxious to suppress the news of the sinking of Audacious, for fear of the demoralising effect it could have on the British public, so he ordered Olympic to be held in custody at Lough Swilly. No communications were permitted and passengers were not allowed to leave the ship. The only people departing her were the crew of Audacious and Chief Surgeon John Beaumont, who was transferring to RMS Celtic. Steel tycoon Charles M. Schwab, who was travelling aboard the liner, sent word to Jellicoe that he had urgent business in London with the Admiralty, and Jellicoe agreed to release Schwab if he remained silent about the fate of Audacious. Finally, on 2 November, Olympic was allowed to go to Belfast where the passengers disembarked.[91]

Naval service

Following Olympic's return to Britain, the White Star Line intended to lay her up in Belfast until the war was over, but in May 1915 she was requisitioned by the Admiralty, to be used as a troop transport, along with the Cunard liners Mauretania and Aquitania. The Admiralty had initially been reluctant to use large ocean liners as troop transports because of their vulnerability to enemy attack; however, a shortage of ships gave them little choice. At the same time, Olympic's other sister ship Britannic, which had not yet been completed, was requisitioned as a hospital ship. Operating in that role she would strike a German naval mine and sink in the Aegean Sea on 21 November 1916.[92]

Stripped of her peacetime fittings and now armed with 12-pounders and 4.7-inch guns, Olympic was converted to a troopship, with the capacity to transport up to 6,000 troops. On 24 September 1915 the newly designated HMT (Hired Military Transport) 2810,[93] now under the command of Bertram Fox Hayes, left Liverpool carrying 6,000 soldiers to Moudros, Greece for the Gallipoli Campaign. On 1 October lifeboats from the French ship Provincia which had been sunk by a U-boat that morning off Cape Matapan were sighted and 34 survivors rescued by Olympic. Hayes was criticised for this action by the British Admiralty, who accused him of putting the ship in danger by stopping her in waters where enemy U-boats were active. The ship's speed was considered to be her best defence against U-boat attack, and such a large ship stopped would have made an unmissable target. However, the French Vice-Admiral Louis Dartige du Fournet took a different view, and awarded Hayes with the Gold Medal of Honour. Olympic made several more trooping journeys to the Mediterranean until early 1916, when the Gallipoli Campaign was abandoned.[94]

In 1916, considerations were made to use Olympic to transport troops to India via the Cape of Good Hope. However, on investigation it was decided that the ship was unsuitable for this role, because the coal bunkers, which had been designed for transatlantic runs, lacked the capacity for such a long journey at a reasonable speed.[95] Instead, from 1916 to 1917, Olympic was chartered by the Canadian Government to transport troops from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Britain.[96] In 1917 she gained 6-inch guns and was painted with a dazzle camouflage scheme to make it more difficult for observers to estimate her speed and heading. Her dazzle colours were brown, dark blue, light blue, and white. Her many visits to Halifax Harbour carrying Canadian troops safely overseas, and back home after the war at Pier 2, made her a favourite symbol in the city of Halifax. Noted Group of Seven artist Arthur Lismer made several paintings of her in Halifax. A large dance hall, the "Olympic Gardens" was also named in her honour.

After the United States declared war on Germany in 1917, Olympic transported thousands of American troops to Britain.[97]

Sinking of U-103

In the early hours of 12 May 1918, while en route for France in the English Channel with U.S. troops under the command of Captain Hayes, Olympic sighted a surfaced U-boat 500 m (1,600 ft) ahead.[98] Olympic's gunners opened fire at once, and the ship turned to ram the submarine, which immediately crash dived to 30 m (98 ft) and turned to a parallel course. Almost immediately afterwards Olympic struck the submarine just aft of her conning tower with her port propeller slicing through U-103's pressure hull. The crew of U-103 blew her ballast tanks, scuttled and abandoned the submarine. Olympic did not stop to pick up survivors, but continued on to Cherbourg. Meanwhile, USS Davis had sighted a distress flare and picked up 31 survivors from U-103. Olympic returned to Southampton with at least two hull plates dented and her prow twisted to one side, but not breached.[99]

It was subsequently discovered that U-103 had been preparing to torpedo Olympic when she was sighted, but the crew were not able to flood the two stern torpedo tubes.[100] For his service, Captain Hayes was awarded the DSO.[101] Some American soldiers on board paid for a plaque to be placed in one of Olympic's lounges to commemorate the event, it read:

This tablet presented by the 59th Regiment United States Infantry commemorates the sinking of the German submarine U103 by Olympic on May 12th 1918 in latitude 49 degrees 16 minutes north longitude 4 degrees 51 minutes west on the voyage from New York to Southampton with American troops...[102]

During the war, Olympic is reported to have carried up to 201,000 troops and other personnel, burning 347,000 tons of coal and travelling about 184,000 miles (296,000 km).[103] Olympic's war service earned her the nickname Old Reliable.[104] Her captain was knighted in 1919 for "valuable services in connection with the transport of troops".[105]

Olympic holds the unofficial award of being the only passenger liner to ram - and sink - a German U-Boat during the First World War.

Post-war

In August 1919 Olympic returned to Belfast for restoration to civilian service. The interiors were modernised and the boilers were converted to oil firing rather than coal burning. This modification would reduce the refuelling time from days to 5 or 6 hours; it also gave a steadier engine R.P.M and allowed the engine room personnel to be reduced from 350 to 60 people.[106] During the conversion work and drydocking, a dent with a crack at the centre was discovered below her waterline which was later concluded to have been caused by a torpedo that had failed to detonate.[107][108] The historian Mark Chirnside concluded that the faulty torpedo had been fired by the U-boat SM U-53 on 4 September 1918, while Olympic was in the English Channel.[109]

Olympic emerged from refit with an increased tonnage of 46,439, allowing her to retain her claim to the title of largest British-built liner afloat, although the Cunard Line's Aquitania was slightly longer. On 25 June 1920 she returned to passenger service, on one voyage that year carrying 2,249 passengers, and carried more than 28,000 passengers throughout the second half of 1920. [110] Olympic transported a record 38,000 passengers during 1921, which proved to be the peak year of her career. With the loss of the Titanic and Britannic, Olympic initially lacked any suitable running mates for the express service; however, in 1922 White Star obtained two former German liners, Majestic and Homeric, which had been given to Britain as war reparations. These joined Olympic as running mates, operating successfully until the Great Depression reduced demand after 1930.[111]

During the 1920s, Olympic remained a popular and fashionable ship, and often attracted the rich and famous of the day; Marie Curie, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, and Prince Edward, then Prince of Wales, were among the celebrities that she carried.[112] Prince Edward and Captain Howarth were filmed on the bridge of Olympic for Pathé News.[113] According to his autobiography,[114] and confirmed by US Immigration records, Cary Grant, then 16-year-old Archibald Leach, first set sail to New York on Olympic on 21 July 1920 on the same voyage on which Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford were celebrating their honeymoon. One of the attractions of Olympic was that she was nearly identical to Titanic, and many passengers sailed on Olympic as a way of vicariously experiencing the voyage of her sister ship.[115] On 22 March 1924, Olympic was involved in another collision with a ship, this time at New York. As Olympic was reversing from her berth at New York harbour, her stern collided with the smaller liner Fort St George, which had crossed into her path. The collision caused extensive damage to the smaller ship. At first it appeared that Olympic had sustained only minor damage, but it was later revealed that her sternpost had been fractured, necessitating the replacement of her entire stern frame.[116]

On 7 June Lord Pirrie died on a business trip aboard RMS Ebro in the Caribbean off Cuba. On 13 June Ebro reached New York; UK ships in the port of New York lowered their flags to half-mast; and Pirrie's body was transferred to Olympic to be repatriated to the UK.[117][118]

Changes in immigration laws in the United States in the 1920s greatly restricted the number of immigrants allowed to enter. The law limited the number of immigrants to about 160,000 per year in 1924.[119] This led to a major reduction in the immigrant trade for the shipping lines, forcing them to cater to the tourist trade to survive.[6] At the turn of 1927–28, Olympic was converted to carry tourist third cabin passengers as well as first, second and third class.[120] Tourist third cabin was an attempt to attract travellers who desired comfort without the accompanying high ticket price. New public rooms were constructed for this class, although tourist third cabin and second class would merge to become 'tourist' by late 1931.

A year later, Olympic's first-class cabins were again improved by adding more bathrooms, a dance floor was fitted in the enlarged first-class dining saloon, and a number of new suites with private facilities were installed forward on B deck.[121] More improvements would follow in a later refit, but 1929 saw Olympic's best average passenger lists since 1925.

On 18 November 1929, as Olympic was travelling westbound near to Titanic's last known position, the ship suddenly started to vibrate violently, and the vibrations continued for two minutes. It was later determined that this had been caused by the 1929 Grand Banks earthquake.[122]

Last years

The shipping trade was badly affected by the Great Depression. Until 1930 there had generally been around one million passengers a year on the transatlantic route, but by 1934 this had dropped by more than half. Furthermore, by the early 1930s, increased competition emerged, in the form of a new generation of larger and faster liners such as Germany's SS Bremen and SS Europa, Italy's SS Rex and France's SS Île de France, and the remaining passengers tended to prefer the more up-to-date ships. Olympic had averaged around 1,000 passengers per journey until 1930, but this declined by more than half by 1932.[123]

Olympic's running mate Homeric was withdrawn from the transatlantic route as early as 1932, leaving only Olympic and Majestic maintaining White Star Line's Southampton-New York service, although this was occasionally augmented during the summer months by either MV Britannic or MV Georgic.[124] During slack periods in the summer, Olympic and fleet mate Majestic were employed in summer recreational cruises from New York to Pier 21 in Halifax, Nova Scotia.[125]

At the end of 1932, with passenger traffic in decline, Olympic went for an overhaul and refit that took four months. She returned to service on 5 March 1933 described by her owners as "looking like new." Her engines were performing at their best and she repeatedly recorded speeds in excess of 23 kn (43 km/h; 26 mph), despite averaging less than that in regular transatlantic service. Passenger capacities were given as 618 first class, 447 tourist class and only 382 third class after the decline of the immigrant trade.[126]

Despite this, during 1933 and 1934, Olympic ran at a net operating loss for the first time. 1933 was Olympic's worst year of business – carrying just over 9,000 passengers in total.[127] Passenger numbers rose slightly in 1934, but many crossings still lost money.[124]

Nantucket lightship collision

In 1934, Olympic again struck another ship. The approaches to New York were marked by lightships and Olympic, like other liners, had been known to pass close by these vessels. On 15 May 1934 (11:06 am), Olympic, inbound in heavy fog, was homing in on the radio beacon of Nantucket Lightship LV-117.[128] Now under the command of Captain John W. Binks, the ship failed to turn in time and sliced through the smaller vessel, which broke apart and sank.[129] Four of the lightship's crew went down with the vessel and seven were rescued, of whom three died of their injuries, seven fatalities out of a crew of eleven.[130] The lightship's surviving crew and Olympic's captain were interviewed soon after reaching shore. One crewman said it all happened so quickly that they did not know how it happened. Olympic reacted quickly lowering boats to rescue the crew, which was confirmed by an injured crewman.[131]

Retirement

In 1934, the White Star Line merged with the Cunard Line at the instigation of the British government, to form Cunard White Star.[132] This merger allowed funds to be granted for the completion of the future Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth. When completed, these two new ships would handle Cunard White Star's express service; so their fleet of older liners became redundant and were gradually retired.

Olympic was withdrawn from the transatlantic service, and left New York for the last time on 5 April 1935, returning to Britain to be laid up in Southampton. The new company considered using her for summer cruises for a short while, but this idea was abandoned and she was put up for sale. Among the potential buyers was a syndicate who proposed to turn her into a floating hotel off the south coast of France, but this came to nothing.[133]

After being laid up for five months alongside her former rival Mauretania, she was sold to Sir John Jarvis – Member of Parliament – for £97,500, to be partially demolished at Jarrow to provide work for the depressed region.[134] On 11 October 1935, Olympic left Southampton for the last time and arrived in Jarrow two days later. The scrapping began after the ship's fittings were auctioned off. Between 1935 and 1937, Olympic's superstructure was demolished, and then on 19 September 1937, her hull was towed to Thos. W. Ward's yard at Inverkeithing for final demolition which was finished by late 1937.[135] At that time, the ship's chief engineer commented, "I could understand the necessity if the 'Old Lady' had lost her efficiency, but the engines are as sound as they ever were".[36]

By the time of her retirement, Olympic had completed 257 round trips across the Atlantic, transporting 430,000 passengers on her commercial voyages, travelling 1.8 million miles.[133][136]

Artefacts

Olympic's fittings were auctioned off before the scrapping commenced.[137]

The fittings of the first-class lounge and part of the aft grand staircase can be found in the White Swan Hotel, in Alnwick, Northumberland, England. A variety of panelling, light fixtures, flooring, doors, and windows from Olympic were installed in a paint factory in Haltwhistle, Northumberland, until they were auctioned in 2004.[138] One suite at Sparth House Hotel, Clayton-le-Moors, Lancashire has the furniture from one of the staterooms, including light fitting, sink, wardrobes and fireplace. The crystal and ormolu electrolier from the lounge is installed in the Cutlers' Hall in Sheffield.[139] Some of the timber panelling was used in the extension (completed in 1937) of St John the Baptist's Catholic Church in Padiham, Lancashire.[140]

In 2000, Celebrity Cruises purchased some of Olympic's original wooden panels to create the "RMS Olympic Restaurant" on board their new cruise ship, Celebrity Millennium. According to the cruise line, this panelling had lined Olympic's À la Carte restaurant.[137]

Olympic's bridge bell is on display at the Titanic Historical Society in Indian Orchard, Springfield, Massachusetts.[141][142]

The clock depicting "Honour and Glory Crowning Time" from Olympic's grand staircase is on display at Southampton's SeaCity Museum.[143][144]

In 1912, a Steinway Vertegrand upright piano No.157550 with a quartered walnut case left the Steinway Hamburg factory unfinished and was sent to its London branch. In 1913, it was decorated by Harland & Wolff's interior decoration company Aldam Heaton & Co with carvings and gold accents. The piano was first placed in the aft starboard corner in the first-class reception room.[145]

In 2017, the old billiard hall at 44 Priestpopple, Hexham, Northumberland, was demolished. During an archaeological excavation on the demolition site by AAG Archaeology, one of the Olympic's chairs was recovered. The fittings from Olympic were auctioned off over ten days in November 1935 at the Palmers Works in Jarrow, the billiard hall opened in 1936.[146]

Identification

Olympic's UK official number was 131346. Official numbers were issued by individual flag states; they should not be confused with IMO numbers.

Until 1933 Olympic's code letters were HSRP[147] and her wireless telegraphy call sign was MKC.[148] In 1930 new four-letter call signs superseded three-letter ones, and in 1934 they also superseded code letters. Olympic's new call sign was GLSQ.[149]

See also

- SS Nomadic – surviving tender to Olympic

- SS Kronprinz Wilhelm, a German passenger ship that, like Olympic, collided with a ship of The Royal Navy (and additionally, like Titanic, with an iceberg).

References

Citations

- ^ Chirnside 2015, p. 34.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Chirnside 2015, p. 39.

- ^ Chirnside 2015, p. 246.

- ^ Chirnside, Mark, RMS Olympic Specification File (November 2007)

- ^ a b c d e f g h "TGOL – Olympic". thegreatoceanliners.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ "Things to do in Northern Ireland".

- ^ a b Chirnside 2004, p. 319.

- ^ Beveridge & Hall 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Le Goff 1998, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Bartlett 2011, p. 25.

- ^ Hutchings & de Kerbrech 2011, p. 12.

- ^ Hutchings & de Kerbrech 2011, p. 14.

- ^ McCluskie 1998, p. 20.

- ^ a b Chirnside 2004, p. 19.

- ^ Eaton & Haas 1995, p. 55.

- ^ Eaton & Haas 1995, p. 56.

- ^ Oceanic II Archived 21 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine – thegreatoceanliners.com

- ^ Piouffre 2009, p. 52.

- ^ McKernan, Luke. "Twenty famous films". Charles Urban.

- ^ Catalogue of Kinemacolor Film Subjects. McGill University Library. 1913. pp. 78–79.

- ^ ""Olympic Class" Film Archive (1908–1937) | William Murdoch".

- ^ Chirnside 2004, pp. 29–30.

- ^ « SS Laurentic (I) », White Star Liners. Accessed 29 June 2009.

- ^ Jamestown Weekly Alert Titanic lacking in safety devices; Jamestown North Dakota, Thursday 18 April 1912

- ^ a b "RMS Olympic – The Old Reliable". titanicandco.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ (in French) Les escaliers de 1 Classe, le Site du Titanic. Retrieved 30 July 2009

- ^ (in French) La Vie à bord du Titanic Archived 6 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, le Site du Titanic. Retrieved 30 July 2009

- ^ (in French) Les Bains Turcs et la Piscine Archived 6 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, le Site du Titanic. Retrieved 30 July 2009

- ^ (in French) Le Gymnase Archived 6 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, le Site du Titanic. Retrieved 30 July 2009

- ^ a b New York Times – Olympic Like A City – 18 June 1911 encyclopedia-titanica.org

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 28.

- ^ "RMS Mauretania".

- ^ Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- ^ a b "The Titanic's Forgotten Sister". Forbes. 1 January 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 41.

- ^ "RMS Olympic". whitestarhistory.com.

- ^ Piouffre 2009, p. 61.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, pp. 43–44.

- ^ "The Huge New Dock at Southampton". Scientific American. 72 (1859). New York: Scientific American Supplement: 114. 19 August 1911. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican08191911-114supp. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Olympic and Titanic: Maiden Voyage Mysteries, by Mark Chirnside and Sam Halpern Archived 6 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine – encyclopaedia-titanica. org

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 45.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 60.

- ^ "ANDREWS, Mr Thomas – Titanic First Class Passenger Biography". titanic-titanic.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 67.

- ^ a b c Marriott, Leo (1997). TITANIC. PRC Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-85648-433-5.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 81.

- ^ RMS Olympic: Titanic's Sister. The History Press. 7 September 2015. ISBN 9780750963480.

- ^ "Olympic". tripod.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "Titanic's unsinkable stoker" Archived 8 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News 30 March 2012

- ^ Beveridge & Hall 2004, p. 76

- ^ Piouffre 2009, p. 89.

- ^ Bonner, Kit; Bonner, Carolyn (2003). Great Ship Disasters. MBI Publishing Company. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-7603-1336-7.

- ^ "Why A Huge Liner Runs Amuck". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. February 1932. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ « Maiden Voyage – Collision With HMS Hawke » Archived 22 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine, RMS Olympic archive. Accessed 21 May 2009.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 76.

- ^ a b Piouffre 2009, p. 70.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, pp. 69–70.

- ^ "Classic Liners and Cruise Ships – RMS Titanic". Cruiseserver.net. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ Titanic Inquiry Project 1912, p. 2

- ^ a b c d "United States Senate Inquiry, Day 18, Proces Verbal (SS Olympic)". Titanic Inquiry Project.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 76.

- ^ "TIP | United States Senate Inquiry | Day 18 | Proces-Verbal (SS Olympic), cont". www.titanicinquiry.org. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ Masson 1998, p. 87.

- ^ a b Chirnside 2004, p. 79.

- ^ "TIP – United States Senate Inquiry – Day 18". titanicinquiry.org. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ a b Chirnside 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Masson 1998, p. 111.

- ^ Brewster & Coulter 1998, p. 78.

- ^ a b "Firemen strike; Olympic held" (PDF). The New York Times. 25 April 1912. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ a b Chirnside 2004, p. 78.

- ^ "Olympic Strikers Make New Demand" (PDF). The New York Times. 26 April 1912. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ "Free Olympic Mutineers" (PDF). The New York Times. 5 May 1912. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 85.

- ^ "The Rebuilt Olympic". The Nautical Gazette. Vol. 83, no. 5. 12 March 1913. pp. 7–8. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Modifications to Olympic following the Titanic disaster – www.titanicology.com

- ^ Chirnside 2004, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Miller, William H (2001). Picture History of British Ocean Liners, 1900 to the Present. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-41532-1.

- ^ List of on board facilities from the Passenger List (First Class) for the White Star Lines steamer RMS "Olympic" for April 28, 1923 voyage from New York to Southampton. pp. 9-10

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 87.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 88.

- ^ a b Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 88.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Hessen, Robert (1990). Steel Titan: The Life of Charles M. Schwab. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822959069. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- ^ Ponsonby, Charles Edward (1920). West Ken (Q. O.) Yeomanry and 10th (yeomanry) Batt. The Buffs, 1914-1919. A. Melrose. p. 8.

- ^ Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- ^ Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 98.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 100.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 101.

- ^ Gibson, Richard Henry; Prendergast, Maurice (1931). The German submarine war, 1914–1918. Constable. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-59114-314-7. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ McCartney, Innes; Jak Mallmann-Showell (2002). Lost Patrols: Submarine Wrecks of the English Channel. Periscope Publishing Ltd. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-904381-04-4.

- ^ "Page 7302 – Supplement 30756, 18 June 1918 – London Gazette – The Gazette". thegazette.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- ^ Kelly Wilson (6 November 2008). "RMS Olympic". Members.aol.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 1998. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 99.

- ^ "Page 11575 – Supplement 31553, 12 September 1919 – London Gazette – The Gazette". thegazette.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 103.

- ^ Olympic II Archived 6 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine titanic-titanic.com

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 102.

- ^ Chirnside, Mark. "Target Olympic: Feuer!" (PDF). markchirnside.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 106.

- ^ Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- ^ Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- ^ "I'm Glad To Be Home". British Pathé. 16 February 1925. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ Archie Leach, Ladies Home Journal Archived 6 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, January/February 1963 (Part 1), March 1963 (Part 2), April 1963 (Part 3)

- ^ Wade, Wyn Craig, "The Titanic: End of a Dream," Penguin Books, 1986 ISBN 978-0-14-016691-0

- ^ Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- ^ "Lord Pirrie dies on ship bound here". The New York Times. 9 June 1924. p. 1. Retrieved 5 March 2024 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Bringing Pirrie's body". The New York Times. 10 June 1924. p. 21. Retrieved 5 March 2024 – via Times Machine.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 111.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 120.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 119.

- ^ Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, pp. 121–131.

- ^ a b Chirnside 2004, p. 135.

- ^ "SS Bismarck/RMS Majestic", Monsters of the Sea: The Great Ocean Liners of Time[usurped]

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 127.

- ^ Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- ^ "History of U.S. Lightships". Palletmastersworkshop.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ Doherty, John (3 September 2004). "Lightship bell raised from ocean's depths". SouthCoastToday.com. Fairhaven. Archived from the original on 10 October 2004. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ "Vessel Designation LV117 (Nantucket)". nightbeacon.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2005.

- ^ ""Olympic" Rams Lightship". British Pathé. 28 May 1934. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ "White Star Line Archives – 1931". Chriscunard.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- ^ a b Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. pp. 136–140. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 137.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 140.

- ^ RMS Olympic: Another Premature Death? – Mark Chirnside Archived 6 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine – encyclopaedia-titanica.org

- ^ a b "Olympic Today". atlanticliners.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ "North Atlantic Run – RMS Olympic Haltwhistle Auction".

- ^ "The Hall and its Collections". Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Padiham – St John the Baptist". Catholic Trust for England and Wales and English Heritage. 2011. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ "Titanic Museums of the World". www.titanicuniverse.com. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "Titanic Museum". Titanichistoricalsociety.org. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "RMS Olympic BL24990_002". Englishheritageimages.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2009. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Collections and Exhibitions". Southampton City Council. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ Chirnside 2015, pp. 59–60

- ^ "Historic find for Hexham billiard hall time team". Hexham Courant. 17 July 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Steamers & Motorships". Lloyd's Register (PDF). Vol. II. Lloyd's Register. 1933. Retrieved 16 February 2021 – via Southampton City Council.

- ^ The Marconi Press Agency Ltd 1914, p. 401.

- ^ "Steamers & Motorships". Lloyd's Register (PDF). Vol. II. Lloyd's Register. 1934. Retrieved 16 February 2021 – via Southampton City Council.

Bibliography

- Bartlett, W.B. (2011). Titanic: 9 Hours to Hell, the Survivors' Story. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-0482-4.

- Beveridge, Bruce; Hall, Steve (2004). Olympic & Titanic. Buy Books. ISBN 978-0-7414-1949-1.

- Brewster, Hugh; Coulter, Laurie (1998). 882 1/2 Amazing Answers to your Questions about the Titanic. Madison Press Book. ISBN 978-0-590-18730-5.

- Chirnside, Mark (2004). The Olympic-Class Ships. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2868-0.

- Chirnside, Mark (2015). RMS Olympic: Titanic's Sister. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-9151-6.

- Eaton, John; Haas, Charles (1995). Titanic, Triumph and Tragedy. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393036978.

- Gardiner, Robert; Van der Vat, Dan (1998). L'Enigme du Titanic (in French). Michel Lafon. ISBN 2840984199.

- Hutchings, David; de Kerbrech, Richard (2011). RMS Titanic Manual: 1909 - 1912 Olympic Class. Voyageur Press. ISBN 9780760340790.

- Le Goff, Olivier (1998). Les Plus Beaux Paquebots du Monde (in French). Solar. ISBN 9782263027994.

- Masson, Philippe (1998). Le drame du "Titanic" (in French). Tallendier. ISBN 223502176X.

- McCluskie, Tom (1998). Anatomy of the Titanic. Thunder Bay Press. ISBN 1571451609.

- The Marconi Press Agency Ltd (1914). The Year Book of Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony. London: The Marconi Press Agency Ltd.

- Piouffre, Gérard (2009). Le Titanic ne répond plus (in French). Larousse. ISBN 978-2-263-02799-4.

- "United States Senate Inquiry. Day 18, Testimony of Herbert J. Haddock and E. J. Moore". Titanic Inquiry Project. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

Further reading

- Hawley, Brian (2012). RMS Olympic. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445600932.

- Layton, J. Kent, Atlantic Liners: A Trio of Trios

- Sisson, Wade (2011). Racing Through the Night – Olympic's Attempt to Reach Titanic. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445600260.

- Talbot, Frederick A. (June 1911). "The Coming of The "Olympic": A Ship That Has Caused Shipyards And Piers To Be Enlarged And Harbors To Be Dredged". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXII: 14507–14515. Retrieved 10 July 2009.