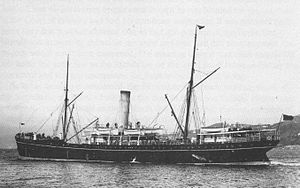

SS Elingamite

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | SS Elingamite |

| Owner | Huddart Parker |

| Builder | C.S. Swan & Hunter, Newcastle upon Tyne, England[1] |

| Yard number | 129 |

| Launched | 6 August 1887 |

| Completed | Sep 1887 |

| Fate | Sank 9 November 1902 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Passenger steamer |

| Tonnage | 2,585 GRT |

| Length | 320 ft (98 m) |

| Beam | 40 ft 9 in (12.42 m) |

| Depth | 22 ft 3 in (6.78 m) |

| Propulsion | Wallsend Slipway & Engineering Company triple-expansion compound steam engines |

| Sail plan | Schooner-rigged |

| Speed | 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph) |

| Capacity | 200 passengers |

| Armament |

|

SS Elingamite was an Australian passenger steamer of 2,585 tons, built in 1887, and owned by Huddart Parker. The ship was wrecked on 9 November 1902[2] off the north coast of New Zealand carrying a large consignment of gold. Now the Elingamite wreck is a favourite site for adventurous divers because of the drama associated with it, and wild tales of lost treasure.

Ship history

Elingamite arrived at Sydney, on 22 November 1887, having departed from Newcastle upon Tyne in England on 24 September, where she had been built by C.S. Swan & Hunter. She was a steel-hulled screw steamer 320 feet (98 m) long, 40 feet 9 inches (12.42 m) in the beam, with a depth of 22 feet 3 inches (6.78 m). She was powered by triple-expansion compound steam engines, built by the Wallsend Slipway & Engineering Company, which gave her a top speed of 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph). There was accommodation for 100 passengers in 1st class, and another 100 in steerage. The Victorian government had selected her for use as an armed cruiser, and she had fittings in place for four Armstrong 36-pounder guns (two forward and two aft), and machine-guns amidships. She was schooner-rigged on two pole masts.[3]

The sinking

Elingamite left Sydney early on Sunday morning, 5 November 1902, on the regular Tasman Sea run between Sydney and Auckland. Captain Ernest Atwood was in charge. On board were 136 passengers and 58 crew, and a consignment of 52 boxes of coins for banks in New Zealand, including 6,000 gold half-sovereigns.

The voyage was uneventful until mid-morning on the 9th when the ship suddenly encountered thick fog. Captain Atwood took necessary precautions, but the vessel struck West Island, one of the islands in the Three Kings group, about 35 nautical miles (65 km) north of Cape Reinga on the northern tip of mainland New Zealand.

The vessel foundered and sank within 20 minutes, but those on board managed to escape in lifeboats and rafts, some taking survivors to King Islands and some to the mainland. One lifeboat was never seen again. 45 people were killed (28 passengers and 17 crew) when the ship foundered. A party of 75 people from three boats landed on a rocky ledge on the middle King Island and after two days were picked up by the SS Zealandia and taken to Auckland. A raft and a fourth boat reached the Great King island and a fifth boat with 52 people on board sailed to Houhora on the North Island, 80 miles away.[4]

Aftermath

A court of enquiry into the sinking began at Auckland on 28 November and lasted about two months. Captain Atwood was found guilty of grossly negligent navigation (and on other matters), and his master's certificate was suspended.

Eight years later the Australian Naval Station reported that the Three Kings were wrongly charted. In 1911, the Terra Nova surveyed the area and established the Three Kings group to be a mile and a quarter south, and a third of a mile east, of their position shown on Captain Atwood's chart.

The enquiry was reopened and the court found that the sinking would never have happened had the chart been accurate. Captain Atwood was cleared of all charges[5] and later became a ship surveyor at Wellington.

Salvage

Over the years there have been exaggerated claims that there was unregistered bullion aboard, and inflated tales about the true value of the coins on board when she sank. It was worth £17,320 (approximately equivalent to $2 million in 2004 US dollars) which was a lot of money, but less than claimed by urban legends. For almost 30 years the Elingamite wreck has been a favourite site for adventurous divers and although widely dispersed and now relatively scarce, some coins have been recovered. The late Kelly Tarlton ran several salvage expeditions to this wreck, during which explosives may have been used to free non-ferrous metals from solidifying precipitate and ferrous corrosion.

The wreck is now privately owned, having passed through several hands after auction of the rights to the wreck by the original insurance company.

See also

- List of disasters in New Zealand by death toll

- Cora Beattie Anderson Roberton, survivor

- Awanui for description of the shipwreck and rescue attempts

References

- ^ "SS Elingamite (1887)". www.tynebuiltships.co.uk. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ "Elingamite shipwreck, 1902". New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ "THE ELINGAMITE". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 23 November 1887. p. 10. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Robb, Douglas (1967). Medical Odyssey. Collins Bros & Co., Ltd. pp. 3–4.

- ^ Te Ara: Encyclopedia of New Zealand 1966 – Elingamite

External links

- Picture from the State Library of Victoria

- The Shipwreck, from the Christchurch Public Library

- Programme of a charity concert for victims

- New Zealand Graphic photos - raft, Zealandia at Queen Street wharf with survivors, lifeboat approaching SS Zealandia, survivors boarding SS Clansman at Hohoura, occupants of the dinghy, occupants of Captain Attwood's boat