SMS Loreley (1885)

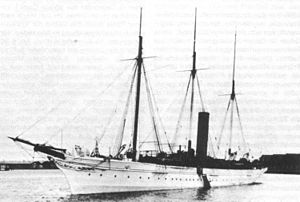

Loreley in 1896 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | SMS Eber |

| Succeeded by | Iltis class |

| Completed | 1 |

| Retired | 1 |

| History | |

| Name | Loreley |

| Namesake | Lorelei |

| Builder | D. and W. Henderson and Company, Glasgow |

| Yard number | 90061 |

| Launched | 1 June 1885 |

| Commissioned | 6 August 1896 |

| Decommissioned | 2 November 1918 |

| Fate | Transferred to private ownership; lost in the Black Sea, January 1926 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Steam yacht |

| Displacement | |

| Length | |

| Beam | 7.4 m (24 ft 3 in) |

| Draft | 4.58 m (15 ft 0 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Sail plan | Schooner |

| Speed | 11.9 kn (22.0 km/h; 13.7 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament | 2 × 5 cm SK L/40 gun |

SMS Loreley was a vessel of the Imperial German Navy which primarily served in the Mediterranean Sea. Originally built as a steam yacht in 1885, the vessel was purchased by Germany in 1896 and was generally stationed at Constantinople, where she was used for diplomatic purposes. Following the end of the First World War, Loreley was sold to a private owner in Turkey, eventually being lost during a voyage in the Black Sea in 1926.

Design

Loreley was constructed as a steam yacht, and was therefore built to a less solid construction than a warship. Consisting of a cross-ribbed structure made of steel, with wooden decks, the hull had a total of six transverse bulkheads. Although considered a good seaboat with easy steering, it tended to roll in heavy seas. The ship's propulsion system was split into separate boiler and engine rooms; she had a single cylinder boiler with four furnaces, which provided steam to a three-cylinder compound steam engine. This allowed the ship to travel at a maximum of 11.9 knots, while its total fuel capacity of 180 tonnes of coal meant a total range of 3,900 nautical miles at a cruising speed of 9 knots. In addition to the steam propulsion equipment, Loreley had a full sailing rig. Rigged as a schooner, the ship's three masts originally had a total sail area of 435 m2. Later in her career, this was reduced when the mizzen mast was requipped with a high sail, reducing the area to 400 m2.[1]

History

Construction and purchase

In 1884, the Glasgow-based shipbuilder D. and W. Henderson and Company received an order from A.H.G. Wittey & Co for the construction of a steam yacht. On 1 June 1885, the new yacht, named Mohican, was launched, eventually being handed to its owners, John and William Clark, industrialists from Largs the following year.[1] John Clark used the yacht extensively, even participating in the rescue of another yacht, the Lilian, in the Atlantic en route to New York in 1887.[2] Mohican was placed up for sale following the death of John Clark in 1894, eventually being purchased by the Imperial German Navy in 1896.[3] At the time, Germany was seeking to replace the paddle steamer aviso SMS Loreley, which was permanently deployed in Constantinople, but which was in urgent need of replacement. Upon the purchase of Mohican, which was given the temporary name Ersatz Loreley, the ship was given a minor refit, which included the addition of a pair of 5 cm SK L/40 guns.[4]

Service

Ersatz Loreley was put into service on 6 August 1896, and was immediately despatched to Constantinople, reaching the city on 7 September. Upon the ship's arrival, the paddle steamer Loreley was decommissioned, with the new ship assuming both its role and its name.[4] The ship's primary purpose was to represent the German Empire in the eastern Mediterranean; to this end, Loreley was often used by the German ambassador for diplomatic purposes, while the ship was also utilised on cruises and port visits in both the Black Sea and the Aegean.[4] In 1898, Loreley was used when Kaiser Wilhelm II visited Turkey, initially escorting the Imperial Yacht Hohenzollern and its accompanying escort, the cruiser Hertha from Tenedos to Constantinople, before taking the Kaiser on a short trip into the Black Sea prior to his visit to the Holy Land.[5]

During its service, Loreley was utilised on a number of occasions by members of the Kaiser's family during visits to the Mediterranean - the ship was placed at the disposal of the Kaiser's mother, Empress Friedrich, during her stay at Lerici in Italy in 1900, while in 1904 Crown Prince Wilhelm and his brother, Prince Eitel Friedrich, used Loreley for their visit to Turkey. Loreley also made many visits to Mediterranean ports with German consulates, where she was used as a registration point for Germans living overseas that had been called up for military service.[4]

In April 1909, Loreley was made ready for potential active service following attacks on the Armenian population in southern Anatolia. The ship departed on 20 April and remained in the area for four days, providing assistance to German and Austro-Hungarian citizens until she was replaced by the light cruiser Hamburg and returned to Constantinople on 27 April. However, on the same day, Sultan Abdul Hamid II was deposed following the Young Turk Revolution. Loreley was used to transport the deposed sultan to Salonika.[6]

The outbreak of the First Balkan War in October 1912 led to an expansion of Germany's naval presence in the Mediterranean. Loreley was assigned to the newly established Mediterranean Division, which also consisted of the battlecruiser Goeben and light cruiser Breslau. The presence of a major German warship in the shape of Goeben relegated Loreley to minor duties, the most notable of which was the return of the former Ottoman sultan to Constantinople in November 1912 as a result of the fall of Salonika to Greek forces.[6] Following maintenance at Alexandria in March 1914, the ship was used by the Kaiser during his visit to Corfu in April 1914. On 12 July, the ship returned to Constantinople following a visit to Smyrna, which proved to be the last visit in peacetime. Following the outbreak of the First World War, Loreley was decommissioned, subsequently serving as a tender and occasional freight carrier in the Sea of Marmara. The ship was returned to active service in December 1917, before finally being decommissioned on 2 November 1918.[7]

Following the end of the war, Loreley was sold to a Turkish operator for use as a freighter. Renamed as Haci Paşa, on 2 January 1926, the ship departed Batum en route to Samsun carrying a cargo of cased petroleum.[3] During the trip, the ship sank somewhere in the Black Sea.[7]

List of commanding officers

| August 1896 to September 1897 | Kapitänleutnant Günther von Krosigk [citation needed] |

| September 1897 to December 1898 | Kapitänleutnant / Korvettenkapitän Job Wilhelm Friedrich von Witzleben |

| December 1898 to October 1900 | Kapitänleutnant / Korvettenkapitän Karl von Levetzow |

| October 1900 to September 1901 | Kapitänleutnant Gottfried von Dalwigk zu Lichtenfels |

| September 1901 to October 1902 | Kapitänleutnant von Rothkirch und Panthen |

| October 1902 to September 1903 | Kapitänleutnant Ludwig von Reuter |

| September 1903 to October 1904 | Kapitänleutnant Walther von Keyserlingk |

| October 1904 to September 1905 | Kapitänleutnant Franz Brüninghaus |

| September 1905 to September 1906 | Kapitänleutnant / Korvettenkapitän Wilhelm von Krosigk |

| September 1906 to October 1907 | Kapitänleutnant Paul Kettner |

| October 1907 to September 1908 | Kapitänleutnant Leberecht von Klitzing |

| September 1908 to September 1909 | Kapitänleutnant / Korvettenkapitän Walter Hildebrand |

| September 1909 to September 1910 | Kapitänleutnant / Korvettenkapitän von Ysenburg-Büdingen |

| September 1910 to October 1911 | Kapitänleutnant / Korvettenkapitän von Gaudecker |

| October 1911 to October 1912 | Kapitänleutnant / Korvettenkapitän Fritz Wossidlo |

| October 1912 to October 1913 | Korvettenkapitän Joachim von Arnim |

| October 1913 to August 1914 | Kapitänleutnant Hans Humann |

| December 1917 to November 1918 | Kapitänleutnant R. Meis |

References

- ^ a b Gröner Vol. 1, p. 168 f.

- ^ "Largs sailor escaped hurricane". Largs & Millport Weekly News. 23 April 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Mohican". Scottish Built Ships. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d Hildebrand/Röhr/Steinmetz: Vol 5, p. 231.

- ^ Hildebrand/Röhr/Steinmetz: Vol 4, p.175

- ^ a b Hildebrand/Röhr/Steinmetz: Vol 5, p. 232

- ^ a b Hildebrand/Röhr/Steinmetz: Vol 5, p. 233

Further reading

- Gröner, Erich; Jung, Dieter; Maass, Martin (1982). German warships 1815-1945 Volume 1: Ironclad Ships, Ships of the Line, Battleships, Aircraft Carriers, Cruisers, Gunboats [Die deutschen Kriegsschiffe 1815–1945. Band 1: Panzerschiffe, Linienschiffe, Schlachtschiffe, Flugzeugträger, Kreuzer, Kanonenboote] (in German). Munich: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-76-374800-6.

- Hildebrand, Hans; Röhr, Albert; Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1981). German warships: Biographies - A Mirror of Naval History from 1815 to the Present Volume 4 [Die deutschen Kriegsschiffe. Biographien - ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart. Band 4] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-78-220235-0.

- Hildebrand, Hans; Röhr, Albert; Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1981). German warships: Biographies - A Mirror of Naval History from 1815 to the Present Volume 5 [Die deutschen Kriegsschiffe. Biographien - ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart. Band 5] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-78-220456-9.