Poetic Edda

| Part of a series on the |

| Norsemen |

|---|

|

| WikiProject Norse history and culture |

The Poetic Edda is the modern name for an untitled collection of Old Norse anonymous narrative poems in alliterative verse. It is distinct from the closely related Prose Edda, although both works are seminal to the study of Old Norse poetry. Several versions of the Poetic Edda exist: especially notable is the medieval Icelandic manuscript Codex Regius, which contains 31 poems.[1]

Composition

The Eddic poems are composed in alliterative verse. Most are in fornyrðislag ("old story metre"), while málaháttr ("speech form") is a common variation. The rest, about a quarter, are composed in ljóðaháttr ("song form"). The language of the poems is usually clear and relatively unadorned. Kennings are often employed, though they do not arise as frequently, nor are they as complex, as those found in typical skaldic poetry.

Authorship

Like most early poetry, the Eddic poems were minstrel poems, passed orally from singer to singer and from poet to poet for centuries. None of the poems are attributed to a particular author, though many of them show strong individual characteristics and are likely to have been the work of individual poets. While scholars have speculated on hypothetical authors, firm and accepted conclusions have never been reached.

Date

Accurate dating of the poems has long been a source of scholarly debate. Firm conclusions are difficult to reach; lines from the Eddic poems sometimes appear in poems by known poets. For example, Eyvindr skáldaspillir composed in the latter half of the 10th century, and he uses a couple of lines in his Hákonarmál that are also found in Hávamál. It is possible that he was quoting a known poem, but it is also possible that Hávamál, or at least the strophe in question, is the younger derivative work.

The few demonstrably historical characters mentioned in the poems, such as Attila, provide a terminus post quem of sorts. The dating of the manuscripts themselves provides a more useful terminus ante quem.

Individual poems have individual clues to their age. For example, Atlamál hin groenlenzku is claimed by its title to have been composed in Greenland and seems so by some internal evidence. If so, it must have been composed no earlier than about 985, since there were no Scandinavians in Greenland until that time.

More certain than such circumstantial evidence are linguistic dating criteria. These can be arrived at by looking at Skaldic poems whose dates are more firmly known. For instance the particle of, corresponding to ga- or ge- in other old Germanic languages, has been shown to occur more frequently in Skaldic poems of earlier date.[2] Applying this criterion to Eddic poetry, Bjarne Fidjestøl found large variation, indicating that some of the poems were much older than others.[3]

Other dating criteria include the use of the negative adverb eigi 'not', and alliteration of vr- with v-. In western dialects of Old Norse the former became r- around the year 1000, but in some Eddic poems the word vreiðr, younger form reiðr, is seen to alliterate with words beginning in an original v-. This was observed already by Olaf ‘White Skald’ Thordarson, the author of the Third Grammatical Treatise, who termed this v before r the vindandin forna; 'the ancient use of vend'.

In some cases, old poems may have been interpolated with younger verses or merged with other poems. For example, stanzas 9–16 of Völuspá, the "Dvergatal" or "Roster of Dwarfs", is considered by some scholars to be an interpolation.

Location

The problem of dating the poems is linked with the problem of determining where they were composed. Iceland was not settled until approximately 870, so anything composed before that time would necessarily have been elsewhere, most likely in Scandinavia. More recent poems, on the other hand, are likely Icelandic in origin.

Scholars have attempted to localize individual poems by studying the geography, flora, and fauna to which they refer. This approach usually does not yield firm results. For example, there are no wolves in Iceland, but we can be sure that Icelandic poets were familiar with the species. Similarly, the apocalyptic descriptions of Völuspá have been taken as evidence that the poet who composed it had seen a volcanic eruption in Iceland – but this is hardly certain.

Codex regius

The Codex Regius is arguably the most important extant source on Norse mythology and Germanic heroic legends. Since the early 19th century, it has had a powerful influence on Scandinavian literature, not only through its stories, but also through the visionary force and the dramatic quality of many of the poems. It has also been an inspiration for later innovations in poetic meter, particularly in Nordic languages, with its use of terse, stress-based metrical schemes that lack final rhymes, instead focusing on alliterative devices and strongly concentrated imagery. Poets who have acknowledged their debt to the Codex Regius include Vilhelm Ekelund, August Strindberg, J. R. R. Tolkien, Ezra Pound, Jorge Luis Borges, and Karin Boye.

The Codex Regius was written during the 13th century, but nothing was known of its whereabouts until 1643, when it came into the possession of Brynjólfur Sveinsson, then Bishop of Skálholt. At the time, versions of the Prose Edda were known in Iceland, but scholars speculated that there once was another Edda, an Elder Edda, which contained the pagan poems that Snorri quotes in his Prose Edda. When Codex Regius was discovered, it seemed that the speculation had proved correct, but modern scholarly research has shown that the Prose Edda was likely written first and that the two were, at most, connected by a common source.[4][page needed]

Brynjólfur attributed the manuscript to Sæmundr the Learned, a larger-than-life 12th century Icelandic priest. Modern scholars reject that attribution, but the name Sæmundar Edda is still sometimes associated with both the Codex Regius and versions of the Poetic Edda using it as a source.

Bishop Brynjólfur sent the manuscript as a present to the Danish king, hence the Latin name Codex Regius, lit. 'Royal Book'. For centuries it was stored in the Royal Library in Copenhagen, but in 1971 it was returned to Iceland. Because air travel at the time was not entirely trustworthy with such precious cargo, it was transported by ship, accompanied by a naval escort.[5]

Contents

Poems similar to those found in the Codex Regius are also included in many editions of the Poetic Edda. Important manuscripts containing these other poems include AM 748 I 4to, Hauksbók, and Flateyjarbók. Many of the poems are also quoted in Snorri's Prose Edda, but usually only in bits and pieces. What poems are included in an edition of the Poetic Edda depends on the editor. Those not found in the Codex Regius are sometimes called the "eddic appendix". Other Eddic-like poems not usually published in the Poetic Edda are sometimes called Eddica minora and were compiled by Andreas Heusler and Wilhelm Ranisch in their 1903 book titled Eddica minora: Dichtungen eddischer Art aus den Fornaldarsögur und anderen Prosawerken.[6]

English translators are not consistent on the translations of the names of the Eddic poems or on how the Old Norse forms should be rendered in English. Up to three translated titles are given below, taken from the translations of Bellows, Hollander, and Larrington with proper names in the normalized English forms found in John Lindow's Norse Mythology and in Andy Orchard's Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend.

Mythological poems

In the Codex Regius

- Völuspá (Wise-woman's prophecy, The Prophecy of the Seeress, The Seeress's Prophecy)

- Hávamál (The Ballad of the High One, The Sayings of Hár, Sayings of the High One)

- Vafþrúðnismál (The Ballad of Vafthrúdnir, The Lay of Vafthrúdnir, Vafthrúdnir's Sayings)

- Grímnismál (The Ballad of Grímnir, The Lay of Grímnir, Grímnir's Sayings)

- Skírnismál (The Ballad of Skírnir, The Lay of Skírnir, Skírnir's Journey)

- Hárbarðsljóð (The Poem of Hárbard, The Lay of Hárbard, Hárbard's Song)

- Hymiskviða (The Lay of Hymir, Hymir's Poem)

- Lokasenna (Loki's Wrangling, The Flyting of Loki, Loki's Quarrel)

- Þrymskviða (The Lay of Thrym, Thrym's Poem)

- Völundarkviða (The Lay of Völund)

- Alvíssmál (The Ballad of Alvís, The Lay of Alvís, All-Wise's Sayings)

Not in the Codex Regius

- Baldrs draumar (Baldr's Dreams)

- Gróttasöngr (The Mill's Song, The Song of Grotti)

- Rígsþula (The Song of Ríg, The Lay of Ríg, The List of Ríg)

- Hyndluljóð (The Poem of Hyndla, The Lay of Hyndla, The Song of Hyndla)

- Völuspá in skamma (The short Völuspá, The Short Seeress' Prophecy, Short Prophecy of the Seeress) - This poem, sometimes presented separately, is often included as an interpolation within Hyndluljóð.

- Svipdagsmál (The Ballad of Svipdag, The Lay of Svipdag) – This title, originally suggested by Bugge, actually covers two separate poems. These poems are late works and not included in most editions after 1950:

- Grógaldr (Gróa's Spell, The Spell of Gróa)

- Fjölsvinnsmál (Ballad of Fjölsvid, The Lay of Fjölsvid)

- Hrafnagaldr Óðins (Odins's Raven Song, Odin's Raven Chant). (A late work not included in most editions after 1900).

- Gullkársljóð (The Poem of Gullkár). (A late work not included in most editions after 1900).

Heroic lays

After the mythological poems, the Codex Regius continues with heroic lays about mortal heroes, examples of Germanic heroic legend. The heroic lays are to be seen as a whole in the Edda, but they consist of three layers: the story of Helgi Hundingsbani, the story of the Nibelungs, and the story of Jörmunrekkr, king of the Goths. These are, respectively, Scandinavian, German, and Gothic in origin. As far as historicity can be ascertained, Attila, Jörmunrekkr, and Brynhildr actually existed, taking Brynhildr to be partly based on Brunhilda of Austrasia, but the chronology has been reversed in the poems.

In the Codex Regius

- The Helgi Lays

- Helgakviða Hundingsbana I or Völsungakviða (The First Lay of Helgi Hundingsbane, The First Lay of Helgi the Hunding-Slayer, The First Poem of Helgi Hundingsbani)

- Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar (The Lay of Helgi the Son of Hjörvard, The Lay of Helgi Hjörvardsson, The Poem of Helgi Hjörvardsson)

- Helgakviða Hundingsbana II or Völsungakviða in forna (The Second Lay of Helgi Hundingsbane, The Second Lay of Helgi the Hunding-Slayer, A Second Poem of Helgi Hundingsbani)

- The Niflung Cycle

- Frá dauða Sinfjötla (Of Sinfjötli's Death, Sinfjötli's Death, The Death of Sinfjötli) (A short prose text.)

- Grípisspá (Grípir's Prophecy, The Prophecy of Grípir)

- Reginsmál (The Ballad of Regin, The Lay of Regin)

- Fáfnismál (The Ballad of Fáfnir, The Lay of Fáfnir)

- Sigrdrífumál (The Ballad of The Victory-Bringer, The Lay of Sigrdrífa)

- Brot af Sigurðarkviðu (Fragment of a Sigurd Lay, Fragment of a Poem about Sigurd)

- Guðrúnarkviða I (The First Lay of Gudrún)

- Sigurðarkviða hin skamma (The Short Lay of Sigurd, A Short Poem about Sigurd)

- Helreið Brynhildar (Brynhild's Hell-Ride, Brynhild's Ride to Hel, Brynhild's Ride to Hell)

- Dráp Niflunga (The Slaying of The Niflungs, The Fall of the Niflungs, The Death of the Niflungs)

- Guðrúnarkviða II (The Second Lay of Gudrún or Guðrúnarkviða hin forna The Old Lay of Gudrún)

- Guðrúnarkviða III (The Third Lay of Gudrún)

- Oddrúnargrátr (The Lament of Oddrún, The Plaint of Oddrún, Oddrún's Lament)

- Atlakviða (The Lay of Atli). The full manuscript title is Atlakviða hin grœnlenzka, that is, The Greenland Lay of Atli, but editors and translators generally omit the Greenland reference as a probable error from confusion with the following poem.

- Atlamál hin groenlenzku (The Greenland Ballad of Atli, The Greenlandish Lay of Atli, The Greenlandic Poem of Atli)

- The Jörmunrekkr Lays

- Guðrúnarhvöt (Gudrún's Inciting, Gudrún's Lament, The Whetting of Gudrún.)

- Hamðismál (The Ballad of Hamdir, The Lay of Hamdir)

Not in the Codex Regius

Several of the legendary sagas contain poetry in the Eddic style. Their age and importance is often difficult to evaluate but the Hervarar saga, in particular, contains interesting poetic interpolations.

- Hlöðskviða (Lay of Hlöd, also known in English as The Battle of the Goths and the Huns), extracted from Hervarar saga.

- The Waking of Angantýr, extracted from Hervarar saga.

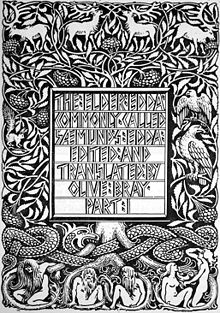

English translations

The Elder or Poetic Edda has been translated numerous times, the earliest printed edition being that by Cottle 1797, though some short sections had been translated as early as the 1670s. Some early translators relied on a Latin translation of the Edda, including Cottle.[7]

Opinions differ on the best way to translate the text, on the use or rejection of archaic language, and the rendering of terms lacking a clear English analogue. Still, Cottle's 1797 translation is now considered very inaccurate.[7]

A comparison of the second and third verses (lines 5–12) of the Vǫluspá is given below:

Ek man jǫtna (Finnur 1932) (unchanged orthography) |

The Jötuns I remember |

I remember the Giants born of yore, |

I remember of yore were born the Jötuns, |

I remember yet the giants of yore, |

I call to mind the kin of etins |

I tell of Giants from times forgotten. |

I remember giants of ages past, |

I, born of giants, remember very early |

I remember giants |

I recall those giants, born early on, |

I remember being reared by Jotuns, |

I remember giants born early in time |

I remember the giants |

| † The prose translation lacks line breaks, inserted here to match those in the Norse verse given in the same work. | |

Allusions and quotations

- As noted above, the Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson makes much use of the works included in the Poetic Edda, though he may well have had access to other compilations that contained the poems and there is no evidence that he used the Poetic Edda or even knew of it.

- The Völsunga saga is a prose version of much of the Niflung cycle of poems. Due to several missing pages (see Great Lacuna) in the Codex Regius, the Völsunga saga is the oldest complete source for the Norse version of much of the story of Sigurð. Only 22 stanzas of the Sigurðarkviða survive in the Codex Regius, plus four stanzas from the missing section which are quoted in the Völsunga saga.

- J. R. R. Tolkien, a philologist and scholar of Old Norse who was familiar with the Eddas, utilized concepts from them in his 1937 fantasy novel The Hobbit, and in other works. For example:

- The Misty Mountains derive from the úrig fiöll in the Skírnismál.[8]

- The names of his Dwarves derive from the Dvergatal in the Vǫluspá.[9]

- His Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún is a verse retelling or reconstruction of the Nibelung poems from the Edda (see Völsunga saga), composed in the Eddaic fornyrðislag metre.

See also

| Part of a series on |

| Old Norse |

|---|

|

| WikiProject Norse history and culture |

References

- ^ John Lindow (2002). Norse Mythology: A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-0-19-983969-8.

- ^ Kuhn, Hans. 1929. Das Füllwort of-um im Altwestnordischen. Eine Untersuchung zur Geschichte der germanischen Präfixe: Ein Beitrag zur altgermanischen Metrik. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- ^ Fidjestøl, Bjarne. 1999. The dating of Eddic poetry: A historical survey and methodological investigation. Edited by Odd Einar Haugen. Copenhagen: C.A. Reitals Forlag.

- ^ Acker, Paul; Larrington, Carolyne (2002), The Poetic Edda: Essays on Old Norse Mythology

- ^ Dodds, Jeramy (2014). The Poetic Edda. Coach House Books. p. 12. ISBN 978-1770563858.

- ^ Harris, Joseph (2005). "Eddic Poetry". Old Norse-Icelandic Literature: A Critical Guide (second ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press in association with the Medieval Academy of America. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-8020-3823-4.

- ^ a b Larrington, Carolyne (2007), Clark, David; Phelpstead, Carl (eds.), "Translating the Poetic Edda into English" (PDF), Old Norse Made New, Viking Society for Northern Research, pp. 21–42

- ^ Shippey, Tom (2003), The Road to Middle-earth, Houghton Mifflin, Ch. 3 pp. 70–71, ISBN 0-618-25760-8

- ^ Ratecliff, John D. (2007), "Return to Bag-End", The History of The Hobbit, vol. 2, HarperCollins, Appendix III, ISBN 978-0-00-725066-0

Further reading

- Anderson, Rasmus B. (1876), Norse Mythology: Myths of the Eddas, Chicago: S.C. Griggs and company; London: Trubner & Co., Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 1-4102-0528-2 , Reprinted 2003

- Björnsson, Árni, ed. (1975), Snorra-Edda, Reykjavík. Iðunn

- Briem, Ólafur, ed. (1985), Eddukvæði, Reykjavík: Skálholt

- Magnússson, Ásgeir Blöndal (1989), Íslensk orðsifjabók, Reykjavík

- Lindow, John (2001), Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-515382-0

- Orchard, Andy (1997), Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend, London: Cassell, ISBN 0-304-36385-5

- von See, Klaus (1997–2019). Kommentar zu den Liedern der Edda [Commentary on the songs of the Edda]. 7 volumes in 8 parts. Heidelberg: Winter.

External links

- Eddukvæði Poetic Edda in Old Norse from heimskringla.no

- The Poetic Edda: Translated from the Icelandic with an Introduction and Notes H. A. Bellows 1923, New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation

- "Eddic to English", www.mimisbrunnr.info , review of all English translations to 2018

- The Elder Eddas of Saemund Sigfusson; and the Younger Eddas of Snorre Sturleson at Project Gutenberg (plain text, HTML and other)

The Elder Edda public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Elder Edda public domain audiobook at LibriVox