Rust

| Steels |

|---|

|

| Phases |

| Microstructures |

| Classes |

| Other iron-based materials |

Rust is an iron oxide, a usually reddish-brown oxide formed by the reaction of iron and oxygen in the catalytic presence of water or air moisture. Rust consists of hydrous iron(III) oxides (Fe2O3·nH2O) and iron(III) oxide-hydroxide (FeO(OH), Fe(OH)3), and is typically associated with the corrosion of refined iron.

Given sufficient time, any iron mass, in the presence of water and oxygen, could eventually convert entirely to rust. Surface rust is commonly flaky and friable, and provides no passivational protection to the underlying iron, unlike the formation of patina on copper surfaces. Rusting is the common term for corrosion of elemental iron and its alloys such as steel. Many other metals undergo similar corrosion, but the resulting oxides are not commonly called "rust".[1]

Several forms of rust are distinguishable both visually and by spectroscopy, and form under different circumstances.[2] Other forms of rust include the result of reactions between iron and chloride in an environment deprived of oxygen. Rebar used in underwater concrete pillars, which generates green rust, is an example. Although rusting is generally a negative aspect of iron, a particular form of rusting, known as stable rust, causes the object to have a thin coating of rust over the top. If kept in low relative humidity, it makes the "stable" layer protective to the iron below, but not to the extent of other oxides such as aluminium oxide on aluminium.[3]

History

It was assumed that rust, made by dissolved oxygen with iron in the oceans, began to sink beneath the seafloor, forming banded iron formations from 2.5 to 2.2 billion years ago. Afterwards, rust soon uplifted iron metals toward the ocean surface. They would subsequently transform into foundations of iron and steel, which effectively fuelled the Industrial Revolution.[citation needed]

Chemical reactions

Rust is a general name for a complex of oxides and hydroxides of iron,[4] which occur when iron or some alloys that contain iron are exposed to oxygen and moisture for a long period of time. Over time, the oxygen combines with the metal, forming new compounds collectively called rust, in a process called rusting. Rusting is an oxidation reaction specifically occurring with iron. Other metals also corrode via similar oxidation, but such corrosion is not called rusting.

The main catalyst for the rusting process is water. Iron or steel structures might appear to be solid, but water molecules can penetrate the microscopic pits and cracks in any exposed metal. The hydrogen atoms present in water molecules can combine with other elements to form acids, which will eventually cause more metal to be exposed. If chloride ions are present, as is the case with saltwater, the corrosion is likely to occur more quickly. Meanwhile, the oxygen atoms combine with metallic atoms to form the destructive oxide compound. These iron compounds are brittle and crumbly and replace strong metallic iron, reducing the strength of the object.

Oxidation of iron

When iron is in contact with water and oxygen, it rusts.[5] If salt is present, for example in seawater or salt spray, the iron tends to rust more quickly, as a result of chemical reactions. Iron metal is relatively unaffected by pure water or by dry oxygen. As with other metals, like aluminium, a tightly adhering oxide coating, a passivation layer, protects the bulk iron from further oxidation. The conversion of the passivating ferrous oxide layer to rust results from the combined action of two agents, usually oxygen and water.

Other degrading solutions are sulfur dioxide in water and carbon dioxide in water. Under these corrosive conditions, iron hydroxide species are formed. Unlike ferrous oxides, the hydroxides do not adhere to the bulk metal. As they form and flake off from the surface, fresh iron is exposed, and the corrosion process continues until either all of the iron is consumed or all of the oxygen, water, carbon dioxide or sulfur dioxide in the system are removed or consumed.[6]

When iron rusts, the oxides take up more volume than the original metal; this expansion can generate enormous forces, damaging structures made with iron. See economic effect for more details.

Associated reactions

The rusting of iron is an electrochemical process that begins with the transfer of electrons from iron to oxygen.[7] The iron is the reducing agent (gives up electrons) while the oxygen is the oxidizing agent (gains electrons). The rate of corrosion is affected by water and accelerated by electrolytes, as illustrated by the effects of road salt on the corrosion of automobiles. The key reaction is the reduction of oxygen:

Because it forms hydroxide ions, this process is strongly affected by the presence of acid. Likewise, the corrosion of most metals by oxygen is accelerated at low pH. Providing the electrons for the above reaction is the oxidation of iron that may be described as follows:

- Fe → Fe2+ + 2 e−

The following redox reaction also occurs in the presence of water and is crucial to the formation of rust:

- 4 Fe2+ + O2 → 4 Fe3+ + 2 O2−

In addition, the following multistep acid–base reactions affect the course of rust formation:

as do the following dehydration equilibria:

From the above equations, it is also seen that the corrosion products are dictated by the availability of water and oxygen. With limited dissolved oxygen, iron(II)-containing materials are favoured, including FeO and black lodestone or magnetite (Fe3O4). High oxygen concentrations favour ferric materials with the nominal formulae Fe(OH)3−xOx⁄2. The nature of rust changes with time, reflecting the slow rates of the reactions of solids.[5]

Furthermore, these complex processes are affected by the presence of other ions, such as Ca2+, which serve as electrolytes which accelerate rust formation, or combine with the hydroxides and oxides of iron to precipitate a variety of Ca, Fe, O, OH species.

The onset of rusting can also be detected in the laboratory with the use of ferroxyl indicator solution. The solution detects both Fe2+ ions and hydroxyl ions. Formation of Fe2+ ions and hydroxyl ions are indicated by blue and pink patches respectively.

Prevention

Because of the widespread use and importance of iron and steel products, the prevention or slowing of rust is the basis of major economic activities in a number of specialized technologies. A brief overview of methods is presented here; for detailed coverage, see the cross-referenced articles.

Rust is permeable to air and water, therefore the interior metallic iron beneath a rust layer continues to corrode. Rust prevention thus requires coatings that preclude rust formation.

Rust-resistant alloys

Stainless steel forms a passivation layer of chromium(III) oxide.[8][9] Similar passivation behavior occurs with magnesium, titanium, zinc, zinc oxides, aluminium, polyaniline, and other electroactive conductive polymers.[10]

Special "weathering steel" alloys such as Cor-Ten rust at a much slower rate than normal, because the rust adheres to the surface of the metal in a protective layer. Designs using this material must include measures that avoid worst-case exposures since the material still continues to rust slowly even under near-ideal conditions.[11]

Galvanization

Galvanization consists of an application on the object to be protected of a layer of metallic zinc by either hot-dip galvanizing or electroplating. Zinc is traditionally used because it is cheap, adheres well to steel, and provides cathodic protection to the steel surface in case of damage of the zinc layer. In more corrosive environments (such as salt water), cadmium plating is preferred instead of the underlying protected metal. The protective zinc layer is consumed by this action, and thus galvanization provides protection only for a limited period of time.

More modern coatings add aluminium to the coating as zinc-alume; aluminium will migrate to cover scratches and thus provide protection for a longer period. These approaches rely on the aluminium and zinc oxides protecting a once-scratched surface, rather than oxidizing as a sacrificial anode as in traditional galvanized coatings. In some cases, such as very aggressive environments or long design life, both zinc and a coating are applied to provide enhanced corrosion protection.

Typical galvanization of steel products that are to be subjected to normal day-to-day weathering in an outside environment consists of a hot-dipped 85 μm zinc coating. Under normal weather conditions, this will deteriorate at a rate of 1 μm per year, giving approximately 85 years of protection.[12]

Cathodic protection

Cathodic protection is a technique used to inhibit corrosion on buried or immersed structures by supplying an electrical charge that suppresses the electrochemical reaction. If correctly applied, corrosion can be stopped completely. In its simplest form, it is achieved by attaching a sacrificial anode, thereby making the iron or steel the cathode in the cell formed. The sacrificial anode must be made from something with a more negative electrode potential than the iron or steel, commonly zinc, aluminium, or magnesium. The sacrificial anode will eventually corrode away, ceasing its protective action unless it is replaced in a timely manner.

Cathodic protection can also be provided by using an applied electrical current. This would then be known as ICCP Impressed Current Cathodic Protection.[13]

Coatings and painting

Rust formation can be controlled with coatings, such as paint, lacquer, varnish, or wax tapes[14] that isolate the iron from the environment.[15] Large structures with enclosed box sections, such as ships and modern automobiles, often have a wax-based product (technically a "slushing oil") injected into these sections. Such treatments usually also contain rust inhibitors. Covering steel with concrete can provide some protection to steel because of the alkaline pH environment at the steel–concrete interface. However, rusting of steel in concrete can still be a problem, as expanding rust can fracture concrete from within.[16][17]

As a closely related example, iron clamps were used to join marble blocks during a restoration attempt of the Parthenon in Athens, Greece, in 1898, but caused extensive damage to the marble by the rusting and swelling of unprotected iron. The ancient Greek builders had used a similar fastening system for the marble blocks during construction, however, they also poured molten lead over the iron joints for protection from seismic shocks as well as from corrosion. This method was successful for the 2500-year-old structure, but in less than a century the crude repairs were in imminent danger of collapse.[18] When only temporary protection is needed for storage or transport, a thin layer of oil, grease or a special mixture such as Cosmoline can be applied to an iron surface. Such treatments are extensively used when "mothballing" a steel ship, automobile, or other equipment for long-term storage.

Special anti-seize lubricant mixtures are available and are applied to metallic threads and other precision machined surfaces to protect them from rust. These compounds usually contain grease mixed with copper, zinc, or aluminium powder, and other proprietary ingredients.[19]

Bluing

Bluing is a technique that can provide limited [citation needed] resistance to rusting for small steel items, such as firearms; for it to be successful, a water-displacing oil is rubbed onto the blued steel and other steel [citation needed].

Inhibitors

Corrosion inhibitors, such as gas-phase or volatile inhibitors, can be used to prevent corrosion inside sealed systems. They are not effective when air circulation disperses them, and brings in fresh oxygen and moisture.

Humidity control

Rust can be avoided by controlling the moisture in the atmosphere.[20] An example of this is the use of silica gel packets to control humidity in equipment shipped by sea.

Treatment

Rust removal from small iron or steel objects by electrolysis can be done in a home workshop using simple materials such as a plastic bucket filled with an electrolyte consisting of washing soda dissolved in tap water, a length of rebar suspended vertically in the solution to act as an anode, another laid across the top of the bucket to act as a support for suspending the object, baling wire to suspend the object in the solution from the horizontal rebar, and a battery charger as a power source in which the positive terminal is clamped to the anode and the negative terminal is clamped to the object to be treated which becomes the cathode.[21] Hydrogen and oxygen gases are produced at the cathode and anode respectively. This mixture is flammable/explosive.[22] Care should also be taken to avoid hydrogen embrittlement. Overvoltage also produces small amounts of ozone, which is highly toxic, so a low voltage phone charger is a far safer source of DC current. The effects of hydrogen on global warming have also recently come under scrutiny. [23]

Rust may be treated with commercial products known as rust converter which contain tannic acid or phosphoric acid which combines with rust; removed with organic acids like citric acid and vinegar or the stronger hydrochloric acid; or removed with chelating agents as in some commercial formulations or even a solution of molasses.[24]

Economic effect

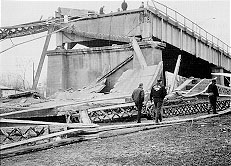

Rust is associated with the degradation of iron-based tools and structures. As rust has a much higher volume than the originating mass of iron, its buildup can also cause failure by forcing apart adjacent parts — a phenomenon sometimes known as "rust packing". It was the cause of the collapse of the Mianus river bridge in 1983, when the bearings rusted internally and pushed one corner of the road slab off its support.

Rust was an important factor in the Silver Bridge disaster of 1967 in West Virginia, when a steel suspension bridge collapsed in less than a minute, killing 46 drivers and passengers on the bridge at the time. The Kinzua Bridge in Pennsylvania was blown down by a tornado in 2003, largely because the central base bolts holding the structure to the ground had rusted away, leaving the bridge anchored by gravity alone.

Reinforced concrete is also vulnerable to rust damage. Internal pressure caused by expanding corrosion of concrete-covered steel and iron can cause the concrete to spall, creating severe structural problems. It is one of the most common failure modes of reinforced concrete bridges and buildings.

- Structural failures caused by rust

- The collapsed Silver Bridge, as seen from the Ohio side

- The Kinzua Bridge after it collapsed

- Rusted and pitted struts of the 70-year-old Nandu River Iron Bridge

Cultural symbolism

Rust is a commonly used metaphor for slow decay due to neglect, since it gradually converts robust iron and steel metal into a soft crumbling powder. A wide section of the industrialized American Midwest and American Northeast, once dominated by steel foundries, the automotive industry, and other manufacturers, has experienced harsh economic cutbacks that have caused the region to be dubbed the "Rust Belt".

In music, literature, and art, rust is associated with images of faded glory, neglect, decay, and ruin.

See also

References

- ^ "Rust, n.1 and adj". OED Online. Oxford University Press. June 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ "Interview, David Des Marais". NASA. 2003. Archived from the original on 2007-11-13.

- ^ Ankersmit, Bart; Griesser-Stermscheg, Martina; Selwyn, Lindsie; Sutherland, Susanne. "Rust Never Sleeps: Recognizing Metals and Their Corrosion Products" (PDF). depotwijzer. Parks Canada. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ Sund, Robert B.; Bishop, Jeanne (1980). Accent on science. C.E. Merrill. ISBN 9780675075695. Archived from the original on 2017-11-30.

- ^ a b "Oxidation Reduction Reactions". Bodner Research Web. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ^ Gräfen, H.; Horn, E. M.; Schlecker, H.; Schindler, H. (2000). "Corrosion". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.b01_08. ISBN 3527306730.

- ^ Ramaswamy, Hosahalli S.; Marcotte, Michele; Sastry, Sudhir; Abdelrahim, Khalid (2014-02-14). Ohmic Heating in Food Processing. CRC Press. ISBN 9781420071092. Archived from the original on 2018-05-02.

- ^ Heinz, Norbert. "Corrosion prevention - HomoFaciens". www.homofaciens.de. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-30.

- ^ "Formation of stable passive film on stainless steel by electrochemical deposition of polypyrrole". Electrochimica Acta.

- ^ "Weathering Steel". azom.com. AZoM. 28 June 2016. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

The steel is allowed to rust and because of its alloy composition rusts more slowly than conventional steel and the rust forms a protective coating slowing the rate of future corrosion

- ^ "Steel corrosion protection - Durability - Structural steel". greenspec.co.uk. greenspec. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

For atmospheric corrosion, refer to the Galvanizers Association Millennium Map of average zinc corrosion rates. About 50% of England and Wales has a rate of under 1 μm/year

- ^ "Cathodic Protection Systems - Matcor, Inc". Matcor, Inc. Archived from the original on 2017-03-30. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ^ "Wax-Tape Anticorrosion Wrap Systems" (PDF). Trenton Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-23. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ^ Schweitzer, Philip A (2007). Corrosion engineering handbook. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-8246-8. OCLC 137248977.

- ^ "Corrosion of Embedded Metals". cement.org. Portland Cement Association. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ "Rust Wedge: Expanding rust is a force strong enough to shatter concrete". exploratorium.edu. 17 April 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ Hadingham, Evan. "Unlocking Mysteries of the Parthenon". smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ "Anti-seize Compounds Information". globalspec.com. Engineering 360. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ Mirza, Lorraine; Gupta, Krishnakali. Young Scientist Series ICSE Chemistry 7. Pearson Education India. ISBN 9788131756591. Archived from the original on 2017-11-30.

- ^ "Rust Removal using Electrolysis". antique-engines.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ^ Smith, Paul (24 June 2022). "Exploding Hydrogen Balloons with Different Amounts of Oxygen". Youtube. Retrieved 2023-12-29.

- ^ Derwent, Richard (2023). "Global warming potential (GWP) for hydrogen: Sensitivities, uncertainties and meta-analysis". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 48 (22): 8328–8341. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.11.219. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ^ "Rust Removal with Molasses". 6 July 2005. Archived from the original on September 25, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

Further reading

- Waldman, J. (2015): Rust – the longest war. Simon & Schuster, New York. ISBN 978-1-4516-9159-7

- Schweitzer, Philip A. (2007). Corrosion engineering handbook. Fundamentals of metallic corrosion : atmospheric and media corrosion of metals (2 ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-8244-4. OCLC 137248972.

- Corrosion of reinforcement in concrete construction. C. L. Page, P. B. Bamforth, J. W. Figg, International Symposium on Corrosion of Reinforcement in Concrete Construction. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry, Information Services. 1996. ISBN 0-85404-731-X. OCLC 35233292.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Corrosion – 2nd Edition (elsevier.com) Volume 1and 2; Editor: L L Shreir ISBN 9781483164106