Rouen faience

The city of Rouen, Normandy has been a centre for the production of faience or tin-glazed earthenware pottery, since at least the 1540s. Unlike Nevers faience, where the earliest potters were immigrants from Italy, who at first continued to make wares in Italian maiolica styles with Italian methods, Rouen faience was essentially French in inspiration, though later influenced by East Asian porcelain. As at Nevers, a number of styles were developed and several were made at the same periods.

The earliest pottery, starting in the 1540s, specialized in large patterns and images made up of coloured tiles. A century later the king granted a fifty-year monopoly, and a factory was established by 1647. The wares this made are now hard to distinguish from those of other centres, but the business was evidently successful. When the monopoly expired in 1697 a number of new factories opened, and Rouen's finest period began, lasting until about the mid-century. The decoration of the best Rouen faience was very well-executed, with intricate designs in several styles, typically centred on ornament, with relatively small figures, if any. By the end of the 18th century production was greatly reduced, mainly because of competition from cheaper and better English creamware.

For a brief period from 1673 to 1696 another factory in the city also made the earliest French soft-paste porcelain, probably not on a commercial basis; only nine pieces of Rouen porcelain are now thought to survive.[1]

Rouen faience

Abaquesne workshops

There are records of "faience in the Italian manner" (maiolica) being made in Rouen in 1526,[2] according to Moon by Masséot Abaquesne,[3] whose workshop was certainly active by the 1540s. He was French, but at least some of his artists may have been Italian. They made painted tiles and also vessels. In 1542–49 they supplied tiles for the Château d'Écouen being built by Anne de Montmorency,[4] the Connétable de France or Grand Constable, chief minister and commander of the French army, who owned an Urbino maiolica service.[5] Another commission from Montmorency's circle was tiling at the Château de la Bastie d'Urfé, built by Claude d'Urfé. Some of these tiles date to c. 1557–60, and after passing through the collections of Gaston Le Breton (1845–1920), a leading art historian of French ceramics, and J. P. Morgan, are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York,[6] which also has three albarellos and a jug by the workshop. In 1543, Masséot signed a contract to supply 346 dozen (4,152) pharmacist's jars to a Rouen apothecary.[7]

Another workshop was started by Masséot's son Laurent Abaquesne and active from about 1545–1590.

- Floor tiles, Château d'Écouen, 1540s

- Albarello, c. 1545

- Tiles with the devices of Claude d'Urfé, from the Château de la Bastie d'Urfé, c. 1557–60

- Single tile from the chapel of the Château de la Bastie d'Urfé

- Tile with head, c. 1549–51

Monopoly period, 1647–97

In 1644, Nicolas Poirel, sieur (lord) of Grandval, obtained a fifty-year royal monopoly over the production of faience in Normandy. A factory was set up by Edme Poterat (1612–87), who was probably an experienced potter, and had reached an arrangement with Poirel. Three pieces dated 1647 are fairly simply decorated in blue on white, with touches of yellow and green.[8]

In 1663 Colbert, recently made Louis XIV's finance minister, made a note that the Rouen faienceries should be protected and encouraged, sent designs, and given commissions by the king.[9] By 1670, Poterat received part of the large and prestigious commissions for Louis XIV's Trianon de porcelaine, now lost. In 1674, Poterat bought out the monopoly from Poirel; he was now evidently prosperous, and acquired two lordships.[10]

On Edme Poterat's death in 1687, his younger son Michel took over the business. Another son, Louis, had started another faiencerie in 1673, and was later to set up a separate factory to make porcelain (see below).[11]

Before the end of the century Rouen faience, apparently led by Louis Poterat (d. 1696), had developed the lambrequin style of decoration, a "baroque scalloped border pattern",[12] with "pendant lacework ornament, drapes and scrollwork",[13] adapted from ornamental styles used in other types of decorative art, including book-bindings, lace and metalwork, and printed versions of them in design-books. Typically large and small elements alternate. This remained a key style, a "virtual trademark" for Rouen,[14] well into the next century, and was often copied in other faience centres, including some outside France, and porcelain factories such as Rouen and Saint-Cloud porcelain. The term derived from scarfs tied to their helmets by medieval knights, and then heraldry, where it is called mantling in English. In French it had also become a term for the horizontal parts (pelmet or window valance) of curtains and hangings, especially around a bed.[15]

After 1697

The end of the Poterat monopoly led to a number of other factories starting up, and it is generally not possible to distinguish between their wares.[16] In 1717, the head of the Poterat family unsuccessfully asked the government to reinstate the monopoly, and suppress six other factories then working in Rouen.[17] Further new factories were established, but the government wished to limit the number, and in particular issued a tableau in 1731 setting out those permitted to make faience and the permitted size of their kilns. In 1734 one manufacturer who had extended his kiln against the tableau was forced to dismantle it. These limits broadly held until the French Revolution although the odd new factory was allowed in later decades.[18] In 1749 there were 13 factories, with 23 kilns between them,[19] and in 1759 a total of 359 workers were employed.[20]

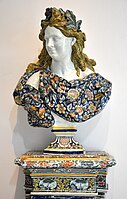

From 1720, Nicolas Fouquay (or Fouquet, d. 1742) bought the main Poterat faiencerie, and was responsible for much of the best work, including a small number of exceptional polychrome busts on stands. A set of the Four Seasons which were made around 1730 for the cabinet (study) of Fouquay's house are now in the Louvre; originally an Apollo now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London completed the group.[21] A pair of uncoloured white busts of Anthony and Cleopatra are now in the ceramic museum in Rouen, and another in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[22] Other exceptionally large pieces are very rare pairs of celestial and terrestrial globes on pedestals, and some large table-tops.[23]

The lambrequin style was originally normally only in blue on white, although a piece dated 1699 already has broderie decoration with a Chinese subject in the centre, using four colours.[24] By 1720, polychrome painting was becoming dominant, using the limited range of colours available for the grand feu technique of a single high-temperature firing.[25] Around the same time the style rayonnant was popular, a version of lambrequin ornament applied to round dishes, with the lambrequins coming inwards from the edges, and then usually a blank area around a circular decorated area. This was also copied by other factories.[26]

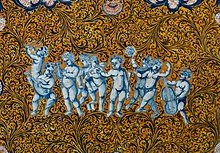

Another decorative style originating in Rouen is called ochre niellé ("inlaid ochre"), with a background of golden-yellow glaze, and painted scrolling decoration of "curling dark blue, seaweed-like foliage", often making way for figures of naked putti or children in the centre of a piece. This is thought to derive from the Boulle work furniture style with inlays of brass and wood on tortoiseshell and other materials associated with André Charles Boulle.[27]

Rouen Chinese styles were varied, and sometimes combined with lambrequins and ochre niellé. After about 1720, styles of floral painting and borders more closely derived from Chinese export porcelain and Japanese styles including Kakiemon grew in popularity. Rococo shapes and styles arrived rather later.[28]

A distinct Rouen style, poised between the Rococo and chinoiserie, is a strongly-coloured decor à la corne, with stylized birds, flowers, butterflies and insects scattered around the field, and a cornucopia corne d'abondance ("horn of plenty"), apparently with four or sometimes three faces, from which flowers emerge. The relative scale of all the elements is incoherent, designed to fill the space neatly. A service of some 200 pieces in this style was commissioned by Tsar Peter III of Russia as a gift for his favourite Count Golovin around 1760.[29]

The Rococo was "never properly understood" in Rouen, where the style was attempted from about 1750. In particular the factories long failed to adapt their shapes to the new style, and they "remained petrified in the silversmith's style of about 1690–1710", often forming "an unsympathetic frame for the sprawling flowers, urns and other paraphernalia of rococo painting".[30]

Rouen ceramics were copied extensively, by manufactories such as the Sinceny manufactory, founded in 1713, when potters from Rouen moved there to establish their own venture, or by Saint-Cloud manufactory.[31]

In 1781, with 25 kilns operating, 570 workers were employed, of whom 95 were painters.[32] Higher figures were claimed later in the decade in petitions to the government.[33] As elsewhere in France, by the eve of the Revolution, the Rouen industry was suffering from the effect of the commercial treaty with Britain of 1786, by which English imports of high-quality, and relatively cheap creamware only had a tariff of 12%.[34] One of the faiencerie owners, M. Huet, was granted 600 livres by the authorities to visit England, and investigate the potteries there. He returned with a plan to establish a factory on the English model, using coal but the plan was frustrated by the political situation. Huet's was one of a number of attempts to imitate English "faience blanche" (white creamware, as opposed to the traditional brown earthenware "faience brune"), but these could not match the strength and cheapness of the English product. By 1796, only nine kilns were in operation, and at a low level, with 150 workers.[35]

- Late 17th-century pot with festoons

- Sugar pourer, c. 1700.

- Vase with lambrequins, and a scene with satyrs, 1700–25

- Winter, c. 1730, made for Nicolas Fouquay's house

- Matching bust of Apollo (stand cut off)

- Polychrome jardiniere with Chinese dragon, 1725–40.

- Polychrome plate with Chinese scene, c. 1730.

- Tureen, decor à la corne, c. 1740

- Chinoiserie plate, c. 1740–45, 24.1 cm.

Notes

- ^ Munger & Sullivan, 135; Battie, 86–87

- ^ Savage (1963), 144

- ^ Moon

- ^ Coutts, 28; "Tiled composition showing the arms of Anne de Montmorency", 1542, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Coutts, 40

- ^ "Tiles with the devices of Claude d'Urfé", c. 1557–60, Masséot Abaquesne, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Giacomotti, French Faience, p. 14, 1963, Oldbourne Press; Revue, 678

- ^ McNab, 22; Savage (1959), 145; Munger & Sullivan, 135; Pottier, 394 listing the pieces, and 10, 69–78 – strictly Poirel's original monopoly was 30 years, extended another 20 the following year, and altered a number of times in later years.

- ^ Pottier, 12

- ^ McNab, 22; Savage (1959), 145–146

- ^ McNab, 22

- ^ Savage & Newman, 174

- ^ Savage (1959), 145 (quoted)

- ^ Moon

- ^ Savage & Newman, 174–175; Savage (1959), 145

- ^ Savage (1959), 146

- ^ Pottier, 19

- ^ Pottier, 19–23

- ^ Pottier, 27

- ^ Pottier, 29

- ^ V&A page; Savage (1959), 146; Lane, 23; Pottier, 19 and see index

- ^ "Bust of Cleopatra (one of a pair), ca. 1720–30", Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Lane, 23

- ^ Pottier, 16

- ^ Savage (1959), 146; Moon

- ^ Savage (1959), 145

- ^ Moon; Lane, 23; "Plateau" (quoted), "Tray", Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Savage (1959), 146; "Plateau", Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Pottier, 312–313

- ^ Lane, 22

- ^ Historic Ornament – Treatise on Decorative Art and Architectural Ornament by James Ward p.64

- ^ Pottier, 34

- ^ Pottier, 35–39

- ^ Pottier, 37

- ^ Pottier, 37, 39–40, 347–349

References

- Battie, David, ed., Sotheby's Concise Encyclopedia of Porcelain, 1990, Conran Octopus, ISBN 1850292515

- Chaffers, William, "The Earliest Porcelain Manufactory in England", in The Art Journal, 1865, google books

- Coutts, Howard, The Art of Ceramics: European Ceramic Design, 1500–1830, 2001, Yale University Press, ISBN 0300083874, 9780300083873, google books

- Lane, Arthur, French Faïence, 1948, Faber & Faber

- McNab, Jessie, Seventeenth-Century French Ceramic Art, 1987, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0870994905, 9780870994906, google books

- Moon, Iris, "French Faience", in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, 2016, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, online

- Munger, Jeffrey, Sullivan Elizabeth, European Porcelain in The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Highlights of the collection, 2018, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 1588396436, 9781588396433, google books

- Pottier, André, Histoire de la faïence de Rouen, Volume 1, 1870, Le Brument (Rouen), google books (in French)

- "Revue", Revue de la Normandie, Volume 9, Eds Gustave Gouellain, Jean Benoît Désiré Cochet, 1869, E. Cagniard, in French, google books

- Savage, George, (1959), Pottery Through the Ages, Penguin, 1959

- Savage, George, (1963), Porcelain Through the Ages, Penguin, (2nd edn.) 1963

- Savage, George, and Newman, Harold, An Illustrated Dictionary of Ceramics, 1985, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0500273804

Further reading

- Perlès, Christophe, La faïence de Rouen (1700–1750) (in French), 2014, Editions Mare et Martin Arts, ISBN 9791092054316