Rollo

| Rollo | |

|---|---|

Rollo as depicted in the 13th century | |

| Count of Rouen | |

| Reign | 911–928 |

| Successor | William Longsword |

| Born | c. 835/870[1][2][3] Scandinavia |

| Died | 933 Duchy of Normandy |

| Burial | |

| Spouses |

|

| Issue more | |

| House | Normandy (founder) |

| Religion |

|

Rollo (Norman: Rou, Rolloun; Old Norse: Hrólfr; French: Rollon; died 933), also known with his epithet, Rollo "the Walker",[4] was a Viking who, as Count of Rouen, became the first ruler of Normandy, a region in today's northern France. He emerged as a leading warrior figure among the Norsemen who had secured a permanent foothold on Frankish soil in the valley of the lower Seine after the Siege of Chartres in 911. Charles the Simple, king of West Francia, in what is called the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, granted Rollo lands between the river Epte and the sea in exchange for Rollo agreeing to end his brigandage, swearing allegiance to him, religious conversion and a pledge to defend the Seine's estuary from other Viking raiders.[5][6]

Rollo's life has been depicted in Dudo of St. Quentin's account. He has been analyzed by European scholars such as W. Vogel, Alexander Bugge, and Henri Prentout, who have debated if Dudo's account can be taken as historically accurate.[7] Rollo's origin and life is heavily debated among different scholars and there is not a clear account of what truthfully happened.

The name Rollo is first recorded in a charter written in 918 as the leader of a group of Viking settlers, and he reigned over the region of Normandy until at least 928. He was succeeded by his son William Longsword in the Duchy of Normandy that he had founded.[8] The offspring of Rollo and his followers, through their intermingling with the indigenous Frankish and Gallo-Roman population of the lands they settled, became known as the "Normans". After the Norman conquest of England and their conquest of southern Italy and Sicily over the following two centuries, their descendants came to rule England, much of Ireland, Sicily and Antioch from the 11th to 13th centuries, leaving behind an enduring legacy in the histories of Europe and the Near East.[9]

Name

The Heimskringla (written in the 13th century) records that Rolf the Ganger went to Normandy and ruled it, so Rollo is generally presumed to be a Latinisation of the Old Norse name Hrólfr, a theory that is supported by the rendition of Hrólfr as Roluo in the Gesta Danorum by Saxo Grammaticus. It is also sometimes suggested that Rollo may be a Latinised version of another Norse name, Hrollaugr.[10]

The 10th-century French historian Dudo in his Historia Normannorum records that Rollo took the baptismal name Robert.[11] A variant spelling, Rou, is used in the 12th-century Norman French verse chronicle Roman de Rou, which was compiled by Wace and commissioned by King Henry II of England, a descendant of Rollo.[12][13]

Origins and historiography

Rollo was born in the mid-9th century as his tomb states he was in his eighties when he died in 933; his place of birth is almost definitely located in the region of Scandinavia, although it is uncertain whether he was Danish or Norwegian. In part, this disparity may result from the indifferent and interchangeable usage in Europe, at the time, of terms such as "Vikings", "Northmen/Norsemen", "Norse", "Swedes", "Danes", "Norwegians" and so on (in the Medieval Latin texts Dani vel Nortmanni means 'Danes or Northmen').

The earliest well-attested historical event associated with Rollo is his part in leading the Vikings who besieged Paris in 885–886 but were fended off by Odo of France.[14][15]

Sources do not make clear the year of Rollo's birth, but from his activity, marriage, children, and death, the mid-9th century may be inferred.

Among biographical remarks about Rollo written by the cleric Dudo of Saint-Quentin in the late 10th century, he claimed that Rollo "the Dane" was from Dacia (a blend of the Latin for Denmark (Dania) and Sweden (Suecia)), and had moved from there to the island of Scandza. One of Rollo's great-grandsons and a contemporary of Dudo was known as Robert the Dane. However, Dudo's Historia Normannorum (or Libri III de moribus et actis primorum Normanniae ducum) was commissioned by Rollo's grandson, Richard I of Normandy and while Dudo likely had access to family members and/or other people with a living memory of Rollo, this fact must be weighed against the text's potential biases, as an official biography.[16]

According to Dudo, an unnamed king of Denmark was antagonistic to Rollo's family, including his father – an unnamed Danish nobleman – and Rollo's brother Gurim. Following the death of their father, Gurim was killed and Rollo was forced to leave Denmark.[17] Dudo appears to have been the main source for William of Jumièges (after 1066) and Orderic Vitalis (early 12th century), although both include additional details.[18]

A Norwegian background for Rollo was first explicitly claimed by Goffredo Malaterra (Geoffrey Malaterra), an 11th-century Benedictine monk and historian, who wrote: "Rollo sailed boldly from Norway with his fleet to the Christian coast."[19] Likewise, the 12th-century English historian William of Malmesbury stated that Rollo was "born of noble lineage among the Norwegians".[20]

A chronicler named Benoît (probably Benoît de Sainte-More) wrote in the mid-12th-century Chronique des ducs de Normandie that Rollo had been born in a town named "Fasge". This has since been variously interpreted as referring to Faxe, in Sjælland (Denmark), Fauske, in Sykkylven (Norway), or perhaps a more obscure settlement that has since been abandoned or renamed. Benoît also repeated the claim that Rollo had been persecuted by a local ruler and had fled from there to "Scanza island", by which Benoît probably means Scania (Swedish Skåne). Benoît says elsewhere in the Chronique that Rollo is Danish.[21]

Snorri Sturluson identified Rollo with Hrólfr the Walker (Norse Göngu-Hrólfr; Danish Ganger-Hrólf) from the 13th-century Icelandic sagas, Heimskringla and Orkneyinga Saga. Hrólf the Walker was so named because he "was so big that no horse could carry him".[22] The Icelandic sources claim that Hrólfr was from Møre[23] in western Norway, in the late 9th century and that his parents were the Norwegian jarl Rognvald Eysteinsson ('Rognvald the Wise') and a noblewoman from Møre named Hildr Hrólfsdóttir. However, these claims were made three centuries after the history commissioned by Rollo's own grandson.

There may be circumstantial evidence for kinship between Rollo and his historical contemporary Ketill Flatnose, King of the Isles – a Norse realm centred on the Western Isles of Scotland. Both Irish and Icelandic sources suggest that Rollo, as a young man, visited or lived in northern Scotland, where he had a daughter named Cadlinar (Kaðlín Kathleen).[24][25] Icelandic sources name Ketill Flatnose's father as Björn Grímsson,[26] which would imply that the name of Ketill Flatnose's paternal grandfather was Grim. That would be limited, onomastic evidence for a connection to Rollo, whose father (according to Richer) was named Ketill, while Rollo also (according to Dudo) had a brother named Gurim – a name likely cognate with Grim. In addition, Icelandic sources report that Rollo's ancestral home was Møre, where Ketill Flatnose's ancestors were also said to have originated. However, there are no surviving sources explicitly claiming a connection; Ketill was a common name in Norse societies,[27] as were names like Gurim/Grim.

Biography

Dudo's chronicle about Rollo seizing Rouen in 876 is supported by the contemporary chronicler Flodoard, who records that Robert of the Breton March waged a campaign against the Vikings, nearly levelling Rouen and other settlements. Eventually, he conceded "certain coastal provinces" to them.[28] Although, scholars have debated this and have said that Rollo did not even arrive in Gaul until after the year 876, making this timeline given in Dudo wrong.[29]

According to Dudo, Rollo struck up a friendship in England with a king called “Alstem”. This has puzzled many historians, but recently this person has been identified as Guthrum, the Danish leader whom Alfred the Great baptised with the name “Athelstan”, and was recognised as King of the East Angles in 880.[30][31]

Dudo recorded that when Rollo controlled Bayeux by force, he carried off the beautiful Popa or Poppa, a daughter of Berenger, Count of Rennes. He married her, and she bore his son and heir, William Longsword.[32] Her parentage is uncertain, and may have been invented after the fact to legitimize her son's lineage, as many of the fantastic genealogical claims made by Dudo were. She may have come from any country with which the Norse had contact, as Dudo is a highly unreliable source who may have written his chronicle primarily as a didactic tool to teach courtly values.[33]

There are few contemporary mentions of Rollo. In 911, Robert I of France, brother of Odo, again defeated another band of Viking warriors in Chartres with his well-trained horsemen. This victory paved the way for Rollo's baptism and settlement in Normandy. In return for formal recognition of the lands he possessed, Rollo agreed to be baptised and assisted the king in defending the realm. As was custom, Rollo took the baptismal name “Robert”, after his godfather, Robert I.[34]

The seal of the agreement was to be a marriage between Rollo and Gisela, daughter of Charles, possibly her legitimate father.[35] Since Charles first married in 907, that would mean that Gisela was at most 5 years old at the time of the treaty of 911 which offered her in marriage.[36] It has therefore been speculated that she could have been an illegitimate daughter.[37] However, a diplomatic child betrothal need not be doubted.[36]

The earliest record of Rollo is from 918, in a charter of Charles III to an abbey, which referred to an earlier grant to "the Normans of the Seine", namely "Rollo and his associates" for "the protection of the kingdom".[38] Dudo retrospectively stated that this pact took place in 911 at Saint-Clair-sur-Epte.

Dudo narrates a humorous story not found in other primary sources about Rollo's pledge of fealty to Charles III as part of the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte. The attendant bishops urged Rollo to kiss the king's foot to prove his allegiance. Rollo refused, saying "I will never bow my knees at the knees of any man, and no man's foot will I kiss."[39] Instead, Rollo commanded one of his warriors to kiss the king's foot. The warrior complied by raising the king's foot to his mouth as the king was standing, which "caused the king to topple backward"[39] much to the amusement of their entourage. On taking his oath of fealty, Rollo divided the lands between the rivers Epte and Risle among his chieftains and settled in the de facto capital of Rouen.[40]

Given Rouen and its hinterland in return for the alliance with the Franks, it was agreed upon that it was in the interests of both Rollo himself and his Frankish allies to extend his authority over Viking settlers.[41] This would appear to be the motive for later concessions to the Vikings of the Seine, which are mentioned in other records of the time. When Charles III was being deposed by Rudolph of France he appealed to Rollo and Ragenold, another one of his Norman allies. With their combined army they marched to his aid in fulfilment of their pledge to the Carolingians, but were stopped at the Oise River by Charles' opponents who traded their cooperation for more territorial concessions.[42] The need for an agreement was particularly urgent when Robert I, successor of Charles III, was killed in 923.[41]

Rudolph was recorded as sponsoring a new agreement by which a group of Norsemen conceded the provinces of the Bessin and Maine. These settlers were presumed to be Rollo and his associates, moving their authority westward from the Seine valley.[41] It is still unclear as to whether Rollo was being given lordship over the Vikings already settled in the region to domesticate and restrain them, or the Franks around Bayeux to protect them from other Viking leaders settled in eastern Brittany and the Cotentin peninsula.[43]

Rollo died sometime between a final mention of him by Flodoard in 928, and 933 – the year in which a third grant of land, usually identified as being the Cotentin and Avranchin areas, was given to his son and successor William.[44]

Rollo's Role in Norman Conversion to Christianity

In Dudo's story of Rollo, he had a vision in which he was on a high mountain on a Frankish dwelling, where he washed himself in a stream and rid himself of the diseases he was infected with. He then saw birds off all kinds gather around the mountain and wash themselves in this stream, which remained together as a whole group and found twigs to build nests. This dream was interpreted to mean the mountain is the church of Christianity, his diseases he rid of where his sins being washed away and born again in the baptism of Christianity. The birds of different types represented the different armies and common people having their sins washed away and communities joined. The nests where the walls of the city to be rebuilt, and all would bow down to Rollo to serve him. Rollo carried this vision with him throughout his journey to Normandy, leading his path. Once he arrived and was granted the land, he dedicated different sections of land to God, Saints, and different Churches. He was baptized and spread the word of Christianity to his followers.[45]

This account of Rollo's role in Christianity has been long debated by scholars. In his 1752 work Micromégas, Voltaire wrote that "peaceful Rollo was the only legislator of his time on the Christian continent". Recently, Scholars have said that Rollo's law-making was the cause of the civilization of Normandy, not his actual conversion to Christianity.[46] While it has been supported that Rollo and his companions did get baptized, it has been argued that this conversion was only formal at first and paganism was still practiced.[47]

Descendants

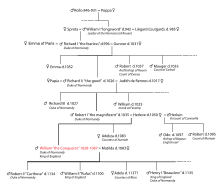

Rollo's son and heir, William Longsword, and grandchild, Richard the Fearless, forged the Duchy of Normandy into West Francia's most cohesive and formidable principality.[48] The descendants of Rollo and his men assimilated with the Frankish culture and became known as the Normans, lending their name to the region of Normandy.[49]

Rollo was the great-great-great-grandfather of William the Conqueror, the progenitor of House of Normandy in England; however, Charles III and the British Royal Family are not direct male-line descendants of Rollo, as the House of Normandy ended with the death of Henry I. However, the House of Plantagenet was influenced by the Norman dynasty, as Empress Matilda, the mother of Henry II of England was the daughter of the Norman king Henry I.

A genetic investigation into the remains of Rollo's grandson Richard the Fearless, and his great-grandson Richard the Good, was announced in 2011 to discern the origins of the historic Viking leader.[50] On 29 February 2016, Norwegian researchers opened Richard the Good's tomb and found a lower jaw with eight teeth in it.[51] However, the skeletal remains in both graves turned out to significantly predate Rollo and therefore are not related to him.[52]

| House of Normandy Family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legacy

Rollo's dynasty survived through a combination of ruthless military action and infighting among the 10th-century Frankish aristocracy, which left them severely weakened and unable to resist the Rouen Vikings’ growing determination to stay put.[53] After Rollo's death, his direct male descendants continued to rule Normandy until Stephen of Blois became King of England and Duke of Normandy in 1135.[54] The duchy was later absorbed into what became the Angevin Empire following its conquest by Geoffrey of Anjou, who in 1128 had married Matilda of England, herself a descendant of Rollo.[55]

Rollo left a legacy of the Founder of Normandy and his leadership and integration of Viking settlers into the region transformed it into a stable political entity.[56] His lineage played a key role in shaping medieval Europe, as it was William the Conqueror, a descendant of Rollo's, who famously led the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. Rollo's baptism also marked a significant point in the assimilation of Viking settlers into Frankish society.

Depictions in fiction

Rollo is the subject of the 17th-century play Rollo Duke of Normandy, also known as The Bloody Brother, written by John Fletcher, Philip Massinger, Ben Jonson, and George Chapman. The similarities to Rollo are slim, as the play draws inspiration from Herodian's account of the rivalry between Emperor Severus's sons, Geta and Antonine. However, the setting shifts from ancient Rome to medieval France, with the brothers reimagined as Otto and Rollo. Initially appointed as co-rulers of the kingdom, Rollo seizes sole power by killing Otto. His reign, marked by tyranny, ultimately ends when he is killed in retribution for his oppressive rule.[57]

A character, broadly inspired by the historical Rollo but including many events predating the historical Rollo's birth, played by Clive Standen, is Ragnar Lothbrok's brother in the History Channel television series Vikings.[58] In the series, Rollo is the brother of Ragnar Lothbrok. Rollo was staying in West Francia to maintain the Viking's hold on the Seine, as a spot to lead future raids. But, the Franks are able to sway him to betray his brother and go through with an acceptance of land and a marriage to the princess Gisla. There are similarities in this story seen in Dudo's, as Rollo settled in West Francia, although there is no mention of betrayal to his brother. He also in the Dudo account marries Charles the Simple's daughter, which is similar to his marriage of princess Gisla.[59]

Rollo is a character in the video game Assassin's Creed Valhalla.[60]

References

Citations

- ^ Bradbury, Jim (2004). The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-415-41395-4.

- ^ Bouet, Pierre (2016). Rollon : Le chef viking qui fonda la Normandie (in French). Tallander. p. 76.

- ^ Hjardar, Kim; Vike, Vegard (2016). Vikings at War. Casemate Publishers & Book Distributors, LLC. p. 329. ISBN 979-1021017467.

- ^ "4 – To Shetland and Orkney". Orkneyinga Saga. pp. 26–27.

- ^ Bates 1982, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Flodoard of Reims 2011, pp. xx–xxi, 14, 16–17

- ^ Douglas, D. C. (1942). Rollo of Normandy. The English Historical Review, 57(228), 417–436. http://www.jstor.org/stable/554369

- ^ "Rollo". Encyclopedia Britannica. 28 August 2008. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Neveux, François; Curtis, Howard (2008). A Brief History of the Normans: The Conquests that Changed the Face of Europe. Robinson. ISBN 978-1-84529-523-3.

- ^ Ferguson 2009, p. 180.

- ^ Crouch 2006.

- ^ Harper-Bill, Christopher; Vincent, Nicholas, eds. (2007). Henry II: New Interpretations. Boydell Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-84383-340-6.

- ^ Wace (2004). Burgess, Glyn S. (ed.). The History of the Norman People: Wace's Roman de Rou. Boydell Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-84383-007-8.

- ^ Little, Charles Eugene (1900). Cyclopedia of Classified Dates: With an Exhaustive Index, by Charles E. Little; for the Use of Students of History, and for All Persons who Desire Speedy Access to the Facts and Events, which Relate to the Histories of the Various Countries of the World, from the Earliest Recorded Dates. Funk & Wagnalls Company. p. 666. OCLC 367478758.

rollo paris 885–886.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (27 November 2018). "Odo of West Francia". World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Dudo 1998, Chapter 5

- ^ Dudo 1998, Chapter 5. Dudo uses the terminology of the day, Scandia for the southern part of the Scandinavian peninsula and Dacia for Denmark (also the name of a Roman province near the Black Sea).

- ^ Ferguson 2009, p. 177.

- ^ Malaterra, Geoffrey (2005). The Deeds of Count Roger of Calabria & Sicily & of Duke Robert Guiscard his brother, Geoffrey Malaterra. Translated by Loud, Graham A. p. 3. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ William of Malmesbury (1989) [1854]. Stephenson, John (ed.). The Kings Before the Norman Conquest. Vol. II, 127. Translated by Sharpe, John. Seeleys, London: Llanerch. p. 110.

- ^ Rollo and his followers are referred to as Daneis throughout the Chronique. For example, Iriez fu Rous en son curage [...] Ne lui nuire n’à ses Daneis (Francisque Michel edition, p. 173, available online via Internet Archive).

- ^ "4 – To Shetland and Orkney". Orkneyinga Saga. pp. 26–27.

- ^ Sturluson, Snorri (1966). King Harald's Saga: Harald Hardradi of Norway. Translated by Magnusson, Magnus; Pálsson, Hermann. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-044183-3.

- ^ Bull, Edvard; Krogvig, Anders; Gran, Gerhard, eds. (1929). Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Vol. 4. Oslo: Aschehoug. pp. 351–353.

- ^ La Fay, Howard (1972). The Vikings. Special Publications. Washington DC: National Geographic Society. p. 146, 147, 164–165. ISBN 978-0-87044-108-0.

- ^ Jennings, Andrew; Kruse, Arne (2009). "From Dál Riata to the Gall-Ghàidheil" (PDF). Viking and Medieval Scandinavia. 5: 129. doi:10.1484/J.VMS.1.100676. hdl:20.500.11820/762e78fe-2a9c-43cf-8173-8300892b31cb. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Woolf, Alex (2007). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. Edinburgh University Press. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-7486-2821-6.

- ^ Van Houts 2000, p. 43.

- ^ Douglas, D. C. (1942). Rollo of Normandy. The English Historical Review, 57(228), 417–436. http://www.jstor.org/stable/554369

- ^ Dudo 1998, p. xiv.

- ^ Ferguson 2009, pp. 177–182.

- ^ Dudo 1998, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Histories, Medieval (11 February 2014). "Dudo of St. Quentin". Medieval Histories. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ "Robert I of France". Britannica Encyclopaedia. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ Dudo 1998, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b Ferguson 2009, p. 187.

- ^ Bauduin, Pierre (2005). "Chefs normands et élites franques, fin IXe–début Xe siècle". In Bauduin, Pierre (ed.). Les Fondations scandinaves en Occident et les débuts du duché de Normandie (in French). CRAHM. p. 182.

- ^ Van Houts 2000, p. 25.

- ^ a b Dudo 1998, pp. 49.

- ^ Bates 1982, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c Crouch 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Flodoard of Reims 2011, Chapter 5, F–K.

- ^ Crouch 2006, p. 8.

- ^ Ferguson 2009, p. 183.

- ^ Dudo of Saint-Quentin (1998). Christiansen, Eric (ed.). Dudo of St Quentin: History of the Normans. Woodbridge. ISBN 978-0-85115-552-4.

- ^ Gilduin Davy, The Laws of Rollo as a Primitive Constitution for Normandy: Writing and Rewriting Legal History in France during the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, The English Historical Review, Volume 138, Issue 594-595, October/December 2023, Pages 1255–1276, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cead178

- ^ 29

- ^ Searle, Eleanor (1988). Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840–1066. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-520-06276-4.

- ^ Brown, R. Allen (1984). The Normans. Boydell & Brewer. p. 16. ISBN 0312577761.

- ^ "Viking is 'forefather to British Royals'". Views and News from Norway. 15 June 2011. Archived from the original on 18 June 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ "Was Viking Ruler Rollo Danish or Norwegian?". The Local. 2 March 2016. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ "Skeletal shock for Norwegian researchers at Viking hunting". Norway Today. 23 November 2016. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ Van Houts 2000, p. 15.

- ^ Huscroft, Richard (2005) "Ruling England, 1042–1217", The English Historical Review, p. 69

- ^ Haskins, Charles H. 1912. "Normandy Under Geoffrey Plantagenet", The English Historical Review, volume 27 (July): 417–444.

- ^ Davy, Gilduin. “The Laws of Rollo as a Primitive Constitution for Normandy: Writing and Rewriting Legal History in France during the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries.” The English Historical Review, vol. 138, no. 594-595, 30 Dec. 2023, pp. 1255–1276, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cead178.

- ^ Culhane, Peter . “Rollo, Duke of Normandy, or the Bloody Brother | the Cambridge Works of Ben Jonson.” Universitypublishingonline.org, 2024, universitypublishingonline.org/cambridge/benjonson/k/dubia/dub_07_Rollo/. Accessed 14 Dec. 2024.

- ^ Turnbow, Tina (18 March 2013). "Reflections of a Viking by Clive Standen". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Dudo of Saint-Quentin (1998). Christiansen, Eric (ed.). Dudo of St Quentin: History of the Normans. Woodbridge. ISBN 978-0-85115-552-4.

- ^ "Old Wounds – Assassin's Creed Valhalla Wiki Guide". IGN. 30 April 2020. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

Sources

- Bates, David (1982). Normandy Before 1066. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-48492-4.

- Crouch, David (2006). The Normans: The History of a Dynasty. A & C Black. ISBN 978-1-85285-595-6. Archived from the original on 2 May 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Dudo of Saint-Quentin (1998). Christiansen, Eric (ed.). Dudo of St Quentin: History of the Normans. Woodbridge. ISBN 978-0-85115-552-4.

- Ferguson, Robert (2009). The Hammer and the Cross: A New History of the Vikings. London: Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-670-02079-9.

- Van Houts, Elizabeth (2000). The Normans in Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4751-0.

Further reading

Primary texts

- Dudo of St. Quentin (1998). Eric Christiansen (ed.). History of the Normans. Translated by Eric Christiansen. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0851155524.

- Elizabeth van Houts, ed. (1992). The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumièges, Orderic Vitalis and Robert of Torigni.

- Elizabeth van Houts, ed. (2000). The Normans in Europe. Translated by Elizabeth van Houts. Manchester and New York: Manchester University.

- Orkneyinga Saga: The History of the Earls of Orkney. Translated by Pálsson, Hermann; Edwards, Paul. London: Hogarth Press. 1978. ISBN 0-7012-0431-1.. Republished 1981, Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044383-5.

Secondary texts

- Crouch, David (2002). The Normans: the History of a Dynasty. London: Hambledon and London. ISBN 1-85285-387-5.

- Christiansen, Eric (2002). The Norsemen in the Viking Age. Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- Fitzhugh, William W.; Ward, Elizabeth (2000). Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Flodoard of Reims (2011). Fanning, Steven; Bachrach, Bernard S. (eds.). The Annals of Flodoard of Reims: 919–966. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-44260-001-0.

- Konstam, Agnus (2002). Historical Atlas of the Viking World. Checkmark Books.