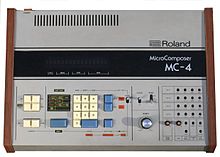

Roland MC-4 Microcomposer

The Roland MC-4 MicroComposer was an early microprocessor-based music sequencer released by Roland Corporation. It could be programmed using the ten key numeric keyboard or a synthesizer keyboard using the keyboard's control voltage and gate outputs. It was released in 1981 with a list price of US$3,295 (equivalent to $11,000 in 2023) (¥430,000 JPY) and was the successor to the MC-8, which in 1977 was the first microprocessor-based digital sequencer.[1] Like its predecessor, the MC-4 is a polyphonic CV/Gate sequencer.[2][3]

Information

This sequencer was released before the advent of MIDI, and viewed by some composers to have more accurate timing. The MC-4 has an output patchbay to the right of the control panel, allowing you to patch the MC-4 to a synthesizer using 3.5mm patch cords. There are four channels of outputs containing CV-1, CV-2, Gate and MPX (multiplex) to control four separate synthesizers.[4] To the left of the output patchbay there are two switches and a control knob. The control knob alters the tempo of the sequencer. The first switch is for cycle mode (which allows the programmed sequence to repeat continuously until the sequencer is stopped), the second switch is for sync control. The MC-4 can be synced to other Roland equipment such as a drum machine or another MC-4 MicroComposer (offering eight separate channels of sequencing).[5]

In the centre of the control panel is the numeric keypad and enter button. To the right of this are two blue keys for moving forward or backwards through a programmed sequence. Below the two advance keys there is another blue button used to tell the MC-4 that you have finished programming a single measure, for example a one bar phrase of notes. To the left of the numeric keypad are six more buttons. These buttons are used for editing the sequence that has been programmed; they include insert, delete, copy-transpose and repeat. The bottom two buttons are for moving the cursor on the screen from left to right.[6]

Concepts in programming

The MC-4 can be programmed with the input of number values, using the control panel numeric keypad. When programming a sequence of notes into the MC-4 numerical values are entered. These correspond to the musical notes on a piano keyboard; Middle C would have the value of 24, increasing upwards for higher notes and downwards for lower notes.[4] Note, however, that Middle C as the value 24 is relative to whatever settings one has set on the synthesizer to be sequenced.

The second concept in programming the MC-4 are time values. The step time values determine the time interval between each musical note, or pitch. To set the time values, one must first set a time base, typically 120. This means that a quarter note = 120, a sixteenth note = 30, an eighth note = 60, etc. Esoteric timings can be programmed by entering any number against whatever time base is entered. The third programming concept is the gate time. This gate time refers to the actual sounded value; whether the phrasing is legato, staccato, semi detached etc.[7]

Alternatively, the MC-4 can record live playing from a monophonic keyboard.

Syncing to MIDI

The MC-4 can be synched to MIDI using a clock to DIN converter. When the MC-4 is powered up, the display will show the TB (time base) default of 120. This is the number of clock pulses per bar; this was the standard before DIN and MIDI clock came into being. If a sequence is programmed while the MC-4 is set to the default TB, it will never sync correctly to DIN or MIDI clock. To sync correctly, the MC-4 TB needs to be set as 48/12/6, this sets the MC-4 for DIN sync and defaults the step time to 16ths (12 clocks) and the gate length to 32nds (6 clocks).

Cassette Storage

After a sequence has been programmed it must be saved, as the memory is volatile: when the power is switched off, memory contents are lost. An optional digital cassette recorder, the Roland MTR-100 was available for this purpose. The owners manual shows that a programmed sequence could also be saved to a standard cassette deck.[8] This is good news as the MTR-100 is quite rare to find.

When saving or loading programs, the CMT (Cassette Memory Transfer) mode must be selected. Programs are saved using program numbers for identification.[9]

Computer-based sequencer programming

In 2011, Defective Records Software released MC-4 Hack, a software application that enables programming of the MC-4's sequencer on computer. It works by creating audio that is routed into the MC-4's cassette input port. This eliminates the need to use the MC-4 calculator-style keypad to enter sequence information.

Roland MC-4 additional options

The Roland MC-4 MicroComposer was able to be used as a stand-alone CV/Gate sequencer, but as the system advanced various additional options were made available for owners needing to use the MC-4 with new tasks and procedures. These involved things like memory expansion, cassette tape media and synthesizer interfaces. Below is a list of additional options that were made available by Roland.[10]

- Roland MTR-100 (Digital Cassette Recorder)

- Roland OP-8 (CV/DCB Interface)

- Roland OP-8M (CV/MIDI Interface)

- Roland OM-4 (Optional Memory that converted an MC-4 into an MC-4B)

Roland MTR-100

The Roland MTR-100 was a digital tape recorder used for storing sequence programmes for the Roland MC-4 MicroComposer. It was offered as an optional accessory for faster data transfer than a standard audio cassette player.[11] When using a Roland MTR-100, the Roland MC-4 MicroComposer needed to be fitted with the additional memory option known as the OM-4. The MTR-100 used digital computer cassettes, Roland endorsed the use of TEAC Computer Tape CT-300 or Maxell Data Cassette Tape CT-300 or M-90.[12]

Notable users

- Aphex Twin (who described it as "like making tracks on a taxi meter")[13]

- The Cars

- Suzanne Ciani[14]

- Vince Clarke (Yazoo, Erasure)[15]

- Depeche Mode

- Devo

- Rusty Egan[16]

- Fad Gadget

- Die Form

- John Foxx (The Garden Studio)

- Front 242

- Heaven 17

- The Human League

- Kontour

- Kraftwerk

- Landscape

- Adrian Lee (Toyah, Mike & the Mechanics)

- Daniel Miller

- Giorgio Moroder

- Masato Nakamura

- Rational Youth[17]

- Martin Rushent

- Tears for Fears

- Isao Tomita

- Toto

- Wang Chung

- Yellow Magic Orchestra

Vince Clarke

Vince Clarke began using the MC-4 on Yazoo's debut album Upstairs at Eric's in 1982. After a good friend noticed that his later albums had changed in sound, Clarke realised this had been due to his having changed from using a Roland MC-4 MicroComposer to using MIDI sequencers. So in 1991 he returned to using MC-4 sequencers for the recording of the Erasure album Chorus. After writing the tracks for the album, they were programmed into a BBC Micro computer, running a UMI sequencing program, to get the arrangements right. The UMI software sequencer was then synced to the MC-4 and all the parts were programmed into the MC-4. The whole theory behind programming with the MC-4 was better timing. Clarke believed at the time that MIDI had timing problems due to data bottlenecks, and CV had much tighter timing. The whole sound of Chorus is due to the MC-4 not being able to program chords; the limitation of only having four channels of sequencing also contributed. At this time he envisaged touring using the MC-4 sequencer.[18] Clarke was later quoted as saying that he bullied the spares department at Roland UK to supply the micro-cassettes needed for data transfer and later described the MC-4 as being "a pig to program but well worth it".

After the recording of the Chorus album Erasure went on tour. He took on the challenge of using a Roland MC-4 as the main sequencer to control various synthesizers live. The synthesizers controlled by the MC-4 included a Minimoog, Roland Juno 60, Sequential Circuits Prophet-5, Oberheim Xpander and a Roland Jupiter 8. For the drums the MC-4 was synced to an Akai MPC60II.[19] Before the tour Clarke's collection of MC-4 sequencers were 'road hardened' by having the chips removed from their sockets and soldered directly to the circuit boards.[18]

Eight MC-4 sequencers were obtained for the tour as back up units, but they were not needed.[19]

References

- ^ Gordon Reid (Nov 2004). "The History Of Roland Part 1: 1930-1978". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

- ^ Roland TR-606 Owner's Manual

- ^ Chris Carter, ROLAND MC8 MICROCOMPOSER, Sound on Sound, Vol.12, No.5, March 1997

- ^ a b page 1, Roland Microcomposer MC-4 Operation Manual

- ^ page 7, Roland Microcomposer MC-4 Operation Manual

- ^ page 8, Roland Microcomposer MC-4 Operation Manual

- ^ page 5, Roland Microcomposer MC-4 Operation Manual

- ^ page 16, Roland Microcomposer MC-4 Operation Manual

- ^ page 18, Roland Microcomposer MC-4 Operation Manual

- ^ Roland MicroComposer MC-4 Operation Manual and Roland OP-8 Operation Manual

- ^ page 91, Roland MicroComposer MC-4 Operation Manual

- ^ page 92, Roland MicroComposer MC-4 Operation Manual

- ^ Noyze, Dave (2014-11-03). "Aphex Twin SYROBONKERS! Interview Part 1". Noyzelab. Archived from the original on 2014-11-03.

- ^ db: The Sound Engineering Magazine, July 1972, page 28

- ^ Ireson, Paul (December 1991). "Sold on the 3-Minute Song". Sound On Sound. United Kingdom. pp. 52–56. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- ^ Rudi Esch, Electri_City: The Düsseldorf School of Electronic Music, Omnibus Press

- ^ "Rational Youth's Brave New World". 6 June 2016.

- ^ a b SOS Magazine, December 1991

- ^ a b Music Technology Magazine, August 1992