Robert de Brus, 6th Lord of Annandale

Sir Robert de Brus | |

|---|---|

| 6th Lord of Annandale jure uxoris Earl of Carrick Constable of Carlisle Castle | |

| Lord of Annandale | |

| Predecessor | Robert V de Brus |

| Successor | Robert VII de Bruce |

| Born | July 1243 probably Writtle, Essex, England |

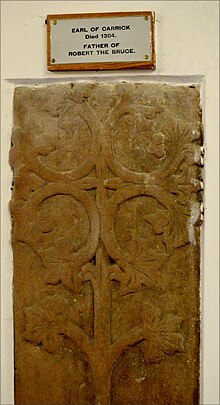

| Died | April 1304 (aged 60) |

| Buried | Holm Cultram Abbey, Cumberland |

| Noble family | Bruce |

| Spouse(s) | Marjorie of Carrick Eleanor |

| Issue |

|

| Father | Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale |

| Mother | Isobel of Gloucester and Hertford |

Robert de Brus (July 1243 – before April 1304[1]), 6th Lord of Annandale, jure uxoris Earl of Carrick[2] (1252–1292), Lord of Hartness,[3] Writtle and Hatfield Broad Oak, was a cross-border lord,[a] and participant of the Second Barons' War, Ninth Crusade, Welsh Wars, and First War of Scottish Independence, as well as father to the future king of Scotland Robert the Bruce.

Of Scoto-Norman-Irish heritage, through his father he was a third-great grandson of David I of Scotland. Other ancestors included Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, Edmund Ironside, Fergus of Galloway, Henry I of England and Aoife MacMurrough, daughter of Dermot MacMurrough.[4]

Life and Family

The son and heir of Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale and Lady Isabella de Clare, daughter of the Earl of Gloucester and Hertford, his birth date is generally accepted, but his place of birth is less certain. It is generally accepted that he, rather than his first son, was born on the family estate at Writtle, Essex.[5][6]

Legend tells that the 27-year-old Robert de Brus was a handsome young man participating in the Ninth Crusade. When Adam de Kilconquhar, one of his companions-in-arms, fell in 1270, at Acre, Robert was obliged to travel to tell the sad news to Adam's widow Marjorie of Carrick. The story continues that Marjorie was so taken with the messenger that she had him held captive until he agreed to marry her, which he did in 1271.[1][7] However, since the crusade landed in Acre on 9 May 1271, and only started to engage the Muslims in late June, the story and/or his participation in the Ninth Crusade are generally discounted.[5][b]

What is recorded, is that, in 1264, his father, the 5th Lord of Annandale, was captured, along with Henry III of England, Richard of Cornwall, and the future Edward I of England at the Battle of Lewes, Sussex. Bruce negotiated with his uncle Bernard Brus, and cousin Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, both supporters of Simon de Montfort, over the terms of the ransom. Following the Battle of Evesham, in August 1265, both Bruce and his father profited from the seizure of the rebellious barons' possessions, including those of Bernard. The younger Robert acquired lands in Yorkshire, Northumberland, and Bedfordshire.[8]

Robert and his younger brother Richard are known to have received letters of protection, in July 1270, to sail with Edward for crusade that August, and are presumed to have taken the cross, with Edward, at Northampton in 1268. They were joined by their father, who had sought pardon from Alexander III, but their date of return from Acre is less certain; it may have been as early as October 1271, when the younger Robert is recorded as receiving a quitclaim in Writtle, Essex, and his mother a gift of deer, from the King, also in Essex.[8]

The marriage between Robert de Brus and Marjorie of Carrick was a strategic union that significantly influenced his political career and legacy. Marjorie, a wealthy and influential heiress, brought significant lands in Carrick along with a strong claim to Scottish nobility, enhancing the political standing of the Brus family.[9][10] Their marriage, which occurred around 1271, was not only a personal union but also a consolidation of power that would later play a key role in the succession of the Scottish throne.[11]

The couple had several children, the most prominent being Robert I of Scotland, known as Robert the Bruce, who would go on to lead Scotland in its fight for independence from England and become King of Scots in 1306.[12] Another of their children, Edward Bruce, played a key role in the Scottish resistance and even briefly became King of Ireland.[13] The legacy of this marriage extended beyond their lifetimes, shaping the future of the Scottish monarchy.[14]

Robert de Brus's claim to the Scottish throne was further solidified by his descent from David I of Scotland, and this royal lineage, coupled with Marjorie's influence, positioned their children to challenge English dominance in Scotland and secure its independence.[15]

Around this time his mother died; the date is unknown but, on 3 May 1273, his father married Christina de Ireby, the Widow of Adam Jesmond, the Sheriff of Northumberland, at Hoddam. The marriage added estates in Cumberland and dower land from her previous husband, to the Brus holdings. The younger Robert and his step-mother do not appear to have got on, with Robert recorded as trying to withhold dower lands, after his father's death in 1295.[8][16][17] This may be one of the reasons why the father appears to have independently managed the possessions in the North, as well as intermittently holding the position of Constable of Carlisle, while Robert appears to have confined himself largely to the management of the southern and Midland possessions, with his brother Richard who independently held Tottenham and Kempston, as well as commanding a Knight banneret for Edward. Richard is recorded as receiving a number of wards and gifts of deer and to have sought permission to empark the forest at Writtle at this time. Robert, while not part of Edward's household, became an envoy and mouthpiece for Alexander III at court, swearing fealty on Alexander's behalf, to Edward at Westminster for Alexander's lands in England, in 1277, as well as following Edward to Gascony[8] Robert is also recorded as following Alexander to Tewkesbury, in the autumn of 1278.[8]

In 1281, he was part of the delegation to Guy of Dampierre, Count of Flanders, to arrange the marriage of Alexander, Prince of Scotland, to Guy's daughter Margaret (d. 1331). The couple married on 14 November 1282 at Roxburgh. In 1282, he participated with his younger brother Richard, who had a command at Denbigh, and is paid for his services in Edward's Conquest of Wales.[8][18] In June 1283, he was summoned by writ to Shrewsbury, for the trial of Dafydd ap Gruffydd.

In February 1284, Bruce attended a convention at Scone, where the right of succession of Alexander III's granddaughter, Margaret, Maid of Norway was recognized.[19] On 1 June 1285 the Earl & Countess of Carrick, at Turnberry, grant the men of Melrose abbey certain freedoms, according to English law.[8]

In 1286, he was witness, along with his son Robert, to the grant of the church of Campbeltown to Paisley Abbey. Also in 1286, he was a signatory to the Band of Turnberry along with his father. In 1290 he was party to the Treaty of Birgham. He supported his father's claim to the vacant throne of Scotland, left so on the death of the Maid of Norway in 1290. The initial civil proceedings, known as the Great Cause, awarded the Crown to his father's first cousin once removed, and rival, John Balliol. In 1291, he swore fealty to Edward I as overlord of Scotland. In 1292, his wife, Marjorie, died. In November, his father, Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale—the unsuccessful claimant—resigned his Lordship of Annandale, and claim to the throne to him, allegedly to avoid having to swear fealty to John.[5] In turn he passed his late wife's Earldom of Carrick, in fee, on to his son Robert.

On 1 January 1293, his warrener at Great Baddow, a Richard, was caught poaching venison at Northle.[8] That same year, he set sail for Bergen, Norway, for the marriage of his daughter Isabel to King Eric II of Norway, the father of the late Maid of Norway, son-in-law of King Alexander III, and a candidate of the Great Cause. Her dowry for the marriage was recorded by Audun Hugleiksson, who noted she brought: precious clothes, 2 golden boiler, 24 silver plate, 4 silver salt cellars, 12 two-handled soup bowls (scyphus), to the Eric's second marriage. In 1294/5 he returned to England.

In May 1295, his father, the 5th Lord of Annandale, died,[19] and on 6 October, Bruce swore fealty to Edward and was made Constable and Keeper of Carlisle Castle, a position his father previously held.[1]

- Refuses a summons to the Scottish host.

- Annandale is seized, by King John Balliol, and given to John "The Red" Comyn, Lord of Badenoch.

- Confirms, to Gisborough Priory, the churches of Annandale and Hart. Witnessed by Walter de Fauconberg and Marmaduke de Thweng.[8]

- Exchanges common pasture, for land held by William of Carlisle at Kinmount.[8]

- Exchanges land in Estfield, for a field adjacent to the prior of Hatfield Regis's manor at Brunesho End Broomshawbury.[8]

- Grants Robert Taper, and his wife Millicent, a messuage in Hatfield Regis, and via a separate grant 5.5 acres (22,000 m2) of arable land 1 acre (4,000 m2) of meadow, in Hatfield Regis, for 16s annual rent.[8]

- Grants John de Bledelowe, the former lands / tenement of Richard de Cumbes, in Hatfield Regis, for 1d annual rent.[8]

- Alters the terms of a grant to Richard de Fanwreyte, of Folewelleshaleyerde, Montpeliers, Writtle, from services to an annual rent. Witnesses includes two of Roberts Cook's at Writtle.[8]

- Alters the terms of a grant to Stephen the Tanner, of Folewelleshaleyerde, Montpeliers, Writtle, from services to an annual rent. Witnesses includes two of Roberts Cook's at Writtle.[8]

- Alters the terms of a grant to Willam Mayhew, of the tenement Barrieland, Hatfield Regis, to an annual rent of 5s and some services.[8]

- Refuses a summons to the Scottish host.

- 1296 Jan, He is summoned to attend to the King Edward at Salisbury

- 26 March, his garrison repels an attack, led by John Comyn, the new Lord of Annandale, across the Solway on Carlisle Castle. Robert forces the raiders to retreat back through Annandale to Sweetheart Abbey.

- 28 April, he again swears fealty to Edward I and fights for Edward, at the Battle of Dunbar Castle.

- August, with his son Robert he renews the pledge of homage and fealty to Edward, at the "victory parliament" in Berwick.

- Edward I denies his claim to the throne and he retires to his estates in Essex.[5]

- 29 August – At Berwick, agrees the dower lands of his widowed step mother, Christina.[8]

- Annandale is re-gained.

- Marries an Eleanor.

- 1298

- 1299

- 1301 November 26 – Grants, Bunnys in Hatfield Broad Oak and Takeley, to an Edward Thurkyld.[8][24]

- After 1301, Enfeoffments Writtle, in part, to a John de Lovetot and his wife Joan.[25][26]

- 1304 Easter, dies en route to Annandale and is buried at Holm Cultram Abbey, Cumberland.[1]

- Following his death his Eleanor remarries, before 8 February 1306 (as his 1st wife) Richard Waleys, Lord Waleys, and they had issue. She died shortly before 8 September 1331.[1]

Shortly after the Battle of Stirling Bridge (1297), Annandale was laid waste as retaliation for the younger Bruce's actions.

When Edward II of returned to England after his victory at the Battle of Falkirk, which John of Fordun accords to Robert turning the Scottish flank:

CI - Battle of Falkirk. :— In the year 1298, the aforesaid king of England, taking it ill that he and his should be put to so much loss and driven to such straits by William Wallace, gathered together a large army, and, having with him, in his company, some of the nobles of Scotland to help him, invaded Scotland. He was met by the aforesaid William, with the rest of the magnates of that kingdom; and a desperate battle was fought near Falkirk, on the 22d of July. William was put to flight, not without serious loss both to the lords and to the common people of the Scottish nation. For, on account of the ill-will, begotten of the spring of envy, which the Comyns had conceived towards the said William, they, with their accomplices, forsook the field, and escaped unhurt. On learning their spiteful deed, the aforesaid William, wishing to save himself and his, hastened to flee by another road. But alas! through the pride and burning envy of both, the noble Estates (communitas) of Scotland lay wretchedly overthrown throughout hill and dale, mountain and plain. Among these, of the nobles, John Stewart, with his Brendans; Macduff, of Fife; and the inhabitants thereof, were utterly cut off. But it is commonly said that Robert of Bruce – who was afterwards king of Scotland, but then fought on the side of the king of England – was the means of bringing about this victory. For, while the Scots stood invincible in their ranks, and could not be broken by either force or stratagem, this Robert of Bruce went with one line, under Anthony of Bek, by a long road round a hill, and attacked the Scots in the rear; and thus these, who had stood invincible and impenetrable in front, were craftily overcome in the rear. And it is remarkable that we seldom, if ever, read of the Scots being overcome by the English, unless through the envy of lords, or the treachery and deceit of the natives, taking them over to the other side.

This is contested as no Bruce appears on the Falkirk roll, of nobles present in the English army, and, ignoring Blind Harry's 15th claim that Wallace burned Ayre Castle in 1297, two 19th-century antiquarians: Alexander Murison and George Chalmers have stated Bruce did not participate in the battle and in the following month decided to burn Ayr Castle, to prevent it being garrisoned by the English. Annandale and Carrick were excepted from the lordships and lands which Edward assigned to his followers, the father having not opposed Edward and the son being treated as a waverer whose allegiance might still be retained.

Robert at that time was old and ill, and there are reports that he wished his son to seek peace with Edward. If not his son's actions could jeopardise his own income, which was primarily derived from his holdings south of the border (estimated £340 versus £150[8]). The elder Bruce would have seen that, if the rebellion failed and his son was against Edward, the son would lose everything, titles, lands, and probably his life.

It was not until 1302 that Robert's son submitted to Edward I. The younger Robert had sided with the Scots since the capture and exile of Balliol. There are many reasons which may have prompted his return to Edward, not the least of which was that the Bruce family may have found it loathsome to continue sacrificing his followers, family and inheritance for King John. There were rumours that John would return with a French army and regain the Scottish throne. Soulis supported his return as did many other nobles, but this would lead to the Bruces losing any chance of gaining the throne themselves.

Family

His first wife was Margery of Carrick, 3rd Countess of Carrick (11 Apr 1254 – November 1292), the daughter and heiress of Niall, 2nd Earl of Carrick.[7] Carrick was a Gaelic Earldom in Southern Scotland. Its territories contained much of today's Ayrshire and Dumfriesshire. The couple married at Turnberry Castle in 1271 and held the principal seats of Turnberry Castle and Lochmaben.

Their children were:

- Isabel Bruce (born c. 1272); married King Eric II of Norway in 1293; d. 1358 in Bergen, Norway.

- Christina Bruce (born c. 1273, Seton, East Lothian); married, firstly, Sir Christopher Seton. Married, secondly, Sir Andrew Murray, 20 September 1305, d. 1356/7, in Scotland.

- King Robert the Bruce (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329); married, firstly, Isabella of Mar; married, secondly, Elizabeth de Burgh.

- Nigel de Brus (Niall or Nigel; born c. 1276); taken prisoner at Kildrummie, hanged, drawn and quartered at Berwick-upon-Tweed in September 1306.[7]

- Edward Bruce (born c. 1279); crowned 2 May 1316, "King of Ireland". Killed in battle, 5 October 1318.[7] Possible marriage to Isabel, daughter of John de Strathbogie, 9th Earl of Atholl – parents of Alexander Bruce, Earl of Carrick; Edward obtained a dispensation for a marriage to Isabella of Ross, daughter of Uilleam II, Earl of Ross, on 1 June 1317.

- Mary Bruce (born c. 1282); married, firstly, Sir Neil Campbell; married, secondly, Sir Alexander Fraser of Touchfraser and Cowie.

- Margaret Bruce (born c. 1283); married Sir William Carlyle.

- Thomas de Brus (born c. 1284); taken prisoner in Galloway, hanged, drawn and quartered 9 February 1307, Carlisle, Cumberland.[7]

- Alexander de Brus (born c. 1285); hanged, drawn and quartered 9 February 1307, Carlisle, Cumberland.

- Elizabeth Bruce (born c. 1286); married Sir William Dishington.

- Matilda/Maud Bruce (born c. 1287); married Hugh, Earl of Ross, in 1308 Orkney Isles, died after September 1323.

He had no children from his second wife Eleanor (died between 13 April and 8 September 1331).

Ancestry

In fiction

He was portrayed (as a leper) by Ian Bannen in the 1995 film Braveheart. Braveheart portrays Robert de Brus as being involved in the capture of William Wallace in Edinburgh; as noted above Robert de Brus died in 1304 and William Wallace was captured on 3 August 1305 by Sir John de Menteith in Glasgow. Menteith was a son-in-law to Gartnait, Earl of Mar and Christina Bruce.

In Outlaw King, he is played by James Cosmo, who had a role in Braveheart as Old Campbell, the father of Wallace's childhood friend. In the 2018 film, de Brus is depicted as lamenting the disintegration of his relationship with Longshanks.

Notes

- ^ The Scottish Baronial Research Group, formed in 1969, first defined the term "Cross-Border Lord", to categorise the Anglo-Norman families with holdings on both sides of the border, the list includes the Balliol, Bruce, Ross and Vescy.

- ^ The contemporary records seem to suggest Robert's father accompanied the Princes Edward and Edmund on the 1270–74 crusade, in lieu of his sons.

References

- ^ a b c d e Richardson, Douglas, Everingham, Kimball G. "Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families", Genealogical Publishing Com, 2005: p732-3, ISBN 0-8063-1759-0, ISBN 978-0-8063-1759-5 link

- ^ Dunbar, Sir Alexander H., Bt., Scottish Kings, a Revised Chronology of Scottish History 1005–1625, Edinburgh, 1899: 126

- ^ "Hartness". history.uk.com.

- ^ "Aoife "Red Eva" MacMurrough (1145-1188) » Ancestral Glimpses » Genealogy Online".

- ^ a b c d Duncan, A. A. M. (September 2004). "Brus, Robert (VI) de, earl of Carrick and lord of Annandale (1243–1304)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3753. Retrieved 29 November 2008., where Robert The Bruce's birthplace is given "at Writtle, near Chelmsford in Essex, on the 11th July 1274".

- ^ le Baker, Geoffrey (1889). Maunde Thompson, Edward (ed.). Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke. Oxford.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e Dunbar, Sir Alexander (1899): 67

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Blakely, Ruth Margaret. The Brus Family in England and Scotland: 1100–1295

- ^ Scott, Ronald McNair (2000). Robert the Bruce: King of Scots. Canongate Books. ISBN 0786703296.

- ^ Fisher, Ian (1987). "Turnberry Castle: A Historical and Archaeological Overview". Transactions of the Ayrshire Archaeological & Natural History Society. 5.

- ^ Penman, Michael (2014). Robert the Bruce: King of the Scots. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300148725.

- ^ Barrow, G.W.S. (1965). Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland. University of California Press. ISBN 0748693300.

- ^ Webster, Bruce (1975). Scotland from the Eleventh Century to 1603. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312121563.

- ^ Duncan, A.A.M. (2002). The Kingship of the Scots, 842-1292: Succession and Independence. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748613182.

- ^ Fraser, George MacDonald (1995). The Steel Bonnets: The Story of the Anglo-Scottish Border Reivers. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780002727464.

- ^ Sayles, George Osborne (1982). Scripta Diversa. A&C Black. ISBN 9780907628125.

- ^ Richardson, Douglas; Everingham, Kimball G. (2005). Magna Carta Ancestry. Genealogical Publishing Company. ISBN 9780806317595.

- ^ Prestwich, Michael, (1988, 1997) Edward I: 196

- ^ a b MacKay 1886.

- ^ Essex Records Office – Deed – D/DBa T4/22

- ^ Essex Records Office – Deed – D/DP T1/1770

- ^ Essex Records Office – Deed – D/DBa T4/24

- ^ Essex Records Office – Deed – D/DBa T2/9

- ^ Essex Records Office – Roll – D/DBa T3/1

- ^ "SC 8/95/4727". nationalarchives.gov.uk. National Archives (UK).

- ^ Burke, Bernard (1848). The Historic Lands of England. Churton, Clayton & Co. p. 120.

- ^ John of Fordun (1363). Skene, William F. (ed.). Chronica Gentis Scotorum [Chronicle of the Scottish Nation] (in Latin). Translated by Felix J. H. Skene. translated 1872.

- Mackay, Aeneas James George (1886). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 7. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 116–117.

- Burke, John & John Bernard (1848). The Royal Families of England, Scotland, and Wales, with Their Descendants. Vol. 1, pedigree XXXIV. London.

- Flower, William, Norroy King of Arms; Northcliffe of Langton (1881). Charles B. (ed.). The Visitation of Yorkshire, 1563/4. London. p. 40.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Scott, Ronald McNair (1989). Robert the Bruce – King of Scots. P. Bedrick Books. ISBN 9780872263208.

- Duncan, A. A. M. (2004). "Brus [Bruce], Robert (VI) de". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3753. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)