Ramsay MacDonald

Ramsay MacDonald | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

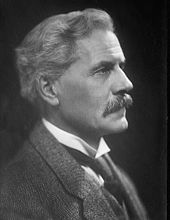

Portrait by Walter Stoneman, 1923 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 5 June 1929 – 7 June 1935 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George V | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 22 January 1924 – 4 November 1924 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George V | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Opposition | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 4 November 1924 – 5 June 1929 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George V | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 21 November 1922 – 22 January 1924 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George V | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | H. H. Asquith | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Labour Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 22 November 1922 – 1 September 1931 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | J. R. Clynes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | J. R. Clynes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Arthur Henderson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 6 February 1911 – 5 August 1914 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chief Whip |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | George Barnes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Arthur Henderson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lord President of the Council | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 7 June 1935 – 28 May 1937 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Halifax | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the House of Commons | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 5 June 1929 – 7 June 1935 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 22 January – 3 November 1924 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Stanley Baldwin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 22 January – 3 November 1924 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | The Marquess Curzon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Austen Chamberlain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | James McDonald Ramsay 12 October 1866 Lossiemouth, Scotland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 9 November 1937 (aged 71) North Atlantic Ocean | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Holy Trinity Church, Spynie | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 6, including Malcolm, Ishbel, Sheila | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Birkbeck, University of London | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Profession | Politician | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

James Ramsay MacDonald (né James McDonald Ramsay; 12 October 1866 – 9 November 1937) was a British statesman[1] and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 and again between 1929 and 1931. From 1931 to 1935, he headed a National Government dominated by the Conservative Party and supported by only a few Labour members. MacDonald was expelled from the Labour Party as a result.

MacDonald, along with Keir Hardie and Arthur Henderson, was one of the three principal founders of the Labour Party in 1900. He was chairman of the Labour MPs before 1914 and, after an eclipse in his career caused by his opposition to the First World War, he was Leader of the Labour Party from 1922. The second Labour Government (1929–1931) was dominated by the Great Depression. He formed the National Government to carry out spending cuts to defend the gold standard, but it had to be abandoned after the Invergordon Mutiny, and he called a general election in 1931 seeking a "doctor's mandate" to fix the economy.

The National coalition won an overwhelming landslide and the Labour Party was reduced to a rump of around 50 seats in the House of Commons. His health deteriorated and he stood down as Prime Minister in 1935, remaining as Lord President of the Council until retiring in 1937. He died later that year.

MacDonald's speeches, pamphlets and books made him an important theoretician. Historian John Shepherd states that "MacDonald's natural gifts of an imposing presence, handsome features and a persuasive oratory delivered with an arresting Highlands accent made him the iconic Labour leader". After 1931, MacDonald was repeatedly and bitterly denounced by the Labour movement as a traitor to its cause. Since the 1960s, some historians have defended his reputation, emphasising his earlier role in building up the Labour Party, dealing with the Great Depression, and as a forerunner of the political realignments of the 1990s and 2000s.[2]

Early life

Lossiemouth

MacDonald was born at Gregory Place, Lossiemouth, Moray, Scotland, the illegitimate son of John MacDonald, a farm labourer, and Anne Ramsay, a housemaid.[3] Registered at birth as James McDonald (sic) Ramsay, he was known as Jaimie MacDonald. Illegitimacy could be a serious handicap in 19th-century Presbyterian Scotland, but in the north and northeast farming communities this was less of a problem; in 1868, a report of the Royal Commission on the Employment of Children, Young Persons and Women in Agriculture noted that the illegitimacy rate was around 15%—nearly every sixth person was born out of wedlock.[4] MacDonald's mother had worked as a domestic servant at Claydale farm, near Alves, where his father was also employed. They were to have been married, but the wedding never took place, either because the couple quarrelled and chose not to marry, or because Anne's mother, Isabella Ramsay, stepped in to prevent her daughter from marrying a man she deemed unsuitable.[5]

Ramsay MacDonald received an elementary education at the Free Church of Scotland school in Lossiemouth from 1872 to 1875, and then at Drainie Parish School. He left school at the end of the summer term in 1881, at the age of 15, and began work on a nearby farm. In December 1881, he was appointed a pupil teacher at Drainie parish school.[6] In 1885, he moved to Bristol to take up a position as an assistant to Mordaunt Crofton, a clergyman who was attempting to establish a Boys' and Young Men's Guild at St Stephen's Church.[7] In Bristol Ramsay MacDonald joined the Democratic Federation, a Radical organisation, which changed its name a few months later to the Social Democratic Federation (SDF).[8][9] He remained in the group when it left the SDF to become the Bristol Socialist Society. In early 1886 he moved to London.[10]

Discovering socialism in London

Following a short period of work addressing envelopes at the National Cyclists' Union in Fleet Street, he found himself unemployed and forced to live on the small amount of money he had saved from his time in Bristol. MacDonald eventually found employment as an invoice clerk in the warehouse of Cooper, Box and Co.[11] During this time he was deepening his socialist credentials, and engaged himself energetically in C. L. Fitzgerald's Socialist Union which, unlike the SDF, aimed to progress socialist ideals through the parliamentary system.[12] MacDonald witnessed the Bloody Sunday of 13 November 1887 in Trafalgar Square, and in response, had a pamphlet published by the Pall Mall Gazette, titled Remember Trafalgar Square: Tory Terrorism in 1887.[13]

MacDonald retained an interest in Scottish politics. Gladstone's first Irish Home Rule Bill inspired the setting-up of a Scottish Home Rule Association in Edinburgh. On 6 March 1888, MacDonald took part in a meeting of London-based Scots, who, upon his motion, formed the London General Committee of the Scottish Home Rule Association.[14] For a while he supported home rule for Scotland, but found little support among London's Scots.[15] However, MacDonald never lost his interest in Scottish politics and home rule, and in Socialism: critical and constructive, published in 1921, he wrote: "The Anglification of Scotland has been proceeding apace to the damage of its education, its music, its literature, its genius, and the generation that is growing up under this influence is uprooted from its past."[16]

Politics in the 1880s was still of less importance to MacDonald than furthering his education. In 1886–87, MacDonald studied botany, agriculture, mathematics, and physics at the Birkbeck Literary and Scientific Institution (now Birkbeck, University of London) but his health suddenly failed him due to exhaustion one week before his examinations, which put an end to any thought of a scientific career.[17] He would however, later be appointed a Governor of the institution in 1895, and continued to have a great fondness for the mission of Birkbeck into his later years.[18]

In 1888, MacDonald took employment as private secretary to Thomas Lough who was a tea merchant and a Radical politician.[19] Lough was elected as the Liberal Member of Parliament (MP) for West Islington, in 1892. Many doors now opened to MacDonald: he had access to the National Liberal Club as well as the editorial offices of Liberal and Radical newspapers; he made himself known to various London Radical clubs among Radical and labour politicians; and he gained valuable experience in the workings of electioneering. At the same time he left Lough's employment to branch out as a freelance journalist. Elsewhere, as a member of the Fabian Society for some time, MacDonald toured and lectured on its behalf at the London School of Economics and elsewhere.[20]

Active politics

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) had created the Labour Electoral Association (LEA) and entered into an unsatisfactory alliance with the Liberal Party in 1886.[21] In 1892, MacDonald was in Dover to give support to the candidate for the LEA in the general election, who was well beaten. MacDonald impressed the local press[22][pages needed] and the Association and was adopted as its candidate, announcing that his candidature would be under a Labour Party banner.[23][page needed] He denied the Labour Party was a wing of the Liberal Party but saw merit in a working political relationship. In May 1894, the local Southampton Liberal Association was trying to find a labour-minded candidate for the constituency. Two others joined MacDonald to address the Liberal Council: one was offered but turned down the invitation, while MacDonald failed to secure the nomination despite strong support among Liberals.[24]

In 1893, Keir Hardie had formed the Independent Labour Party (ILP) which had established itself as a mass movement. In May 1894 MacDonald applied for membership and was accepted. He was officially adopted as the ILP candidate for one of the Southampton seats on 17 July 1894[25][page needed] but was heavily defeated at the election of 1895. MacDonald stood for Parliament again in 1900 for one of the two Leicester seats; he lost, and was accused of splitting the Liberal vote to allow the Conservative candidate to win.[26] That same year he became Secretary of the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), the forerunner of the Labour Party, allegedly in part because many delegates confused him with prominent London trade unionist Jimmie MacDonald when they voted for "Mr. James R. MacDonald".[27] MacDonald retained membership of the ILP; while it was not a Marxist organisation it was more rigorously socialist than the Labour Party would prove to be, and ILP members would operate as a "ginger group" within the Labour Party for many years.[28]

As Party Secretary, MacDonald negotiated an agreement with the leading Liberal politician Herbert Gladstone (son of the late Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone), which allowed Labour to contest a number of working class seats without Liberal opposition,[29] thus giving Labour its first breakthrough into the House of Commons. He married Margaret Ethel Gladstone, who was unrelated to the Gladstones of the Liberal Party, in 1896. Although not wealthy, Margaret MacDonald was comfortably well off,[30] and this allowed them to indulge in foreign travel, visiting Canada and the United States in 1897, South Africa in 1902, Australia and New Zealand in 1906 and India several times.

It was during this period that MacDonald and his wife began a long friendship with the social investigator and reforming civil servant Clara Collet[31][32] with whom he discussed women's issues. She was an influence on MacDonald and other politicians in their attitudes towards women's rights. In 1901, he was elected to the London County Council for Finsbury Central as a joint Labour–Progressive Party candidate, but he was disqualified from the register in 1904 due to his absences abroad.[33][incomplete short citation]

In 1906, the LRC changed its name to the "Labour Party", amalgamating with the ILP.[34] In that same year, 29 Labour MPs were elected, including MacDonald, for Leicester,[35][page needed] who then became one of the leaders of the Parliamentary Labour Party. These Labour MPs undoubtedly owed their election to the 'Gladstone–MacDonald pact' between the Liberals and Labour, a minor party supporting the Liberal governments of Henry Campbell-Bannerman and H. H. Asquith. MacDonald became the leader of the left-wing of the party, arguing that Labour must seek to displace the Liberals as the main party of the left.[36][incomplete short citation]

Party Leadership

Mr. Ramsay MacDonald (Champion of Independent Labour). "Of course I'm all for peaceful picketing—on principle. But it must be applied to the proper parties."

Cartoon from Punch 20 June 1917

In 1911 MacDonald became "Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party", the leader of the party. He was the chief intellectual leader of the party, paying little attention to class warfare and much more to the emergence of a powerful state as it exemplified the Darwinian evolution of an ever more complex society. He was an Orthodox Edwardian progressive, keen on intellectual discussion, and averse to agitation.[37]

Within a short period, his wife became ill with blood poisoning and died. This deeply and permanently affected MacDonald.[38]

MacDonald had always taken a keen interest in foreign affairs and knew from his visit to South Africa, just after the Boer War had ended, what the effects of modern conflict would be. Although the Parliamentary Labour Party generally held an anti-war opinion, when war was declared in August 1914, patriotism came to the fore.[39] After the Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, warned the House of Commons on 3 August that war with Germany was likely, MacDonald responded by declaring that "this country ought to have remained neutral".[40][41] In the Labour Leader he claimed that the real cause of the war was the "policy of the balance of power through alliance".[42]

The Party supported the government in its request for £100,000,000 of war credits and, as MacDonald could not, he resigned from the party Chairmanship. Arthur Henderson became the new leader, while MacDonald took the party Treasurer's post.[43] Despite his opposition to the war, MacDonald visited the Western Front in December 1914 with the approval of Lord Kitchener. MacDonald and General Seely set off for the front at Ypres and soon found themselves in the thick of an action in which both behaved with the utmost coolness. Later, MacDonald was received by the Commander-in-Chief at St Omer and made an extensive tour of the front. Returning home, he paid a public tribute to the courage of the French troops, but said nothing then or later of having been under fire himself.[44]

During the early part of the war, he was extremely unpopular and was accused of treason and cowardice. Former Liberal Party MP and publisher Horatio Bottomley attacked him through his magazine John Bull in September 1915, by publishing an article carrying details of MacDonald's birth and his so-called deceit in not disclosing his real name.[45][46] His illegitimacy was no secret and he had not seemed to have suffered by it, but, according to the journal he had, by using a false name, gained access to parliament falsely and should suffer heavy penalties and have his election declared void. MacDonald received much internal support, but how the disclosures were made public had affected him.[47] He wrote in his diary:

...I spent hours of terrible mental pain. Letters of sympathy began to pour in upon me. ... Never before did I know that I had been registered under the name of Ramsay, and cannot understand it now. From my earliest years, my name has been entered in lists, like the school register, etc. as MacDonald.

In August 1916 the Moray Golf Club passed a resolution declaring that MacDonald's anti-war activities "had endangered the character and interests of the club" and that he had forfeited his right to membership.[48] In January 1917 MacDonald published National Defence, in which he argued that open diplomacy and disarmament were necessary to prevent future wars.[49]

As the war dragged on, his reputation recovered but he still lost his seat in the 1918 "Coupon Election", which saw the Liberal David Lloyd George's coalition government win a large majority. The election campaign in Leicester West focused on MacDonald's opposition to the war, with MacDonald writing after his defeat: "I have become a kind of mythological demon in the minds of the people".[50]

MacDonald denounced the Treaty of Versailles: "We are beholding an act of madness unparalleled in history".[51]

In Opposition

1920–1923

MacDonald stood for Parliament in the 1921 Woolwich East by-election and lost. His opponent, Captain Robert Gee, had been awarded the Victoria Cross at Cambrai; MacDonald tried to counter this by having ex-soldiers appear on his platforms. MacDonald also promised to pressure the government into converting the Woolwich Arsenal to civilian use.[52] Horatio Bottomley intervened in the by-election, opposing MacDonald's election because of his anti-war record.[53] Bottomley's influence may have been decisive in MacDonald's failure to be elected as there were under 700 votes difference between Gee and MacDonald.[54]

In 1922, MacDonald was returned to the House as MP for Aberavon in Wales, with a vote of 14,318 against 11,111 and 5,328 for his main opponents. His rehabilitation was complete; the Labour New Leader magazine opined that his election was, "enough in itself to transform our position in the House. We have once more a voice which must be heard".[55] By now, the party was reunited and MacDonald was re-elected as Leader. Historian Kenneth O. Morgan examines his newfound stature:

- as dissolution set in with the Lloyd George coalition in 1921–22, and unemployment mounted, MacDonald stood out as the leader of a new kind of broad-based left. His opposition to the war had given him a new charisma. More than anyone else in public life, he symbolised peace and internationalism, decency and social change.... [He] had become The voice of conscience.[56]

At the 1922 election, Labour replaced the Liberals as the main opposition party to the Conservative government of Stanley Baldwin, making MacDonald Leader of the Opposition. By now, he had moved away from the Labour left and abandoned the socialism of his youth: he strongly opposed the wave of radicalism that swept through the labour movement in the wake of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and became a determined enemy of Communism. Unlike the French Section of the Workers' International and the Social Democratic Party of Germany, the Labour Party did not split and the Communist Party of Great Britain remained small and isolated.

In 1922, MacDonald visited Palestine.[57] In a later account of his visit, he contrasted Zionist pioneers with 'the rich plutocratic Jew'.[57] MacDonald believed the latter "was the true economic materialist. He is the person whose views upon life make one anti-Semitic. He has no country, no kindred. Whether as a sweater or a financier, he is an exploiter of everything he can squeeze. He is behind every evil that Governments do, and his political authority, always exercised in the dark, is greater than that of Parliamentary majorities. He is the keenest of brains and the bluntest of consciences. He detests Zionism because it revives the idealism of his race, and has political implications which threaten his economic interests."[57]

MacDonald became noted for "woolly" rhetoric such as the occasion at the Labour Party Conference of 1930 at Llandudno when he appeared to imply unemployment could be solved by encouraging the jobless to return to the fields "where they till and they grow and they sow and they harvest". Equally, there were times when it was unclear what his policies were. There was already some unease in the party about what he would do if Labour was able to form a government.[58]

Election of 1923

At the 1923 election, the Conservatives had lost their majority, and when they lost a vote of confidence in the House in January 1924, King George V called on MacDonald to form a minority Labour government, with the tacit support of the Liberals under Asquith from the corner benches. On 22 January 1924,[59] he took office as the first Labour Prime Minister,[60] the first from a working-class background[60] and one of the very few without a university education.[61]

Prime Minister (1924)

First term: January–October 1924

MacDonald had never held office but demonstrated energy, executive ability, and political astuteness. He consulted widely within his party, making the Liberal Lord Haldane the Lord Chancellor, and Philip Snowden Chancellor of the Exchequer. He took the foreign office himself.[59] Besides himself, ten other cabinet members came from working-class origins, a dramatic breakthrough in British history.[62] His first priority was to undo the perceived damage caused by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, by settling the reparations issue and coming to terms with Germany. King George V noted in his diary, "He wishes to do the right thing.... Today, 23 years ago, dear Grandmama [Queen Victoria] died. I wonder what she would have thought of a Labour Government!"[63]

While there were no major labour strikes during his term, MacDonald acted swiftly to end those that did erupt. When the Labour Party executive criticised the government, he replied that "public doles, Poplarism [local defiance of the national government], strikes for increased wages, limitation of output, not only are not Socialism, but may mislead the spirit and policy of the Socialist movement".[64] The Government lasted only nine months and did not have a majority in either House of the Parliament, but it was still able to support the unemployed with the extension of benefits and amendments to the Insurance Acts. In a personal triumph for John Wheatley, Minister for Health, a Housing Act was passed, which greatly expanded municipal housing for low-paid workers.[65]

Foreign affairs

MacDonald had long been a leading spokesman for internationalism in the Labour movement; at first, he verged on pacifism. He founded the Union of Democratic Control in early 1914 to promote international socialist aims, but it was overwhelmed by the war. His 1917 book, National Defence, revealed his own long-term vision for peace. Although disappointed at the harsh terms of the Versailles Treaty, he supported the League of Nations – but, by 1930, he felt that the internal cohesion of the British Empire and a strong, independent British defence programme might turn out to be the wisest British government policy.[66]

MacDonald moved in March 1924 to end construction work on the Singapore military base, despite strong opposition from the Admiralty. He believed the building of the base would endanger the disarmament conference; the First Sea Lord Lord Beatty considered the absence of such a base as dangerously imperilling British trade and territories East of Aden and could mean the security of the British Empire in the Far East being dependent on the goodwill of Japan.[67]

In June 1924, MacDonald convened a conference in London of the wartime Allies and achieved an agreement on a new plan for settling the reparations issue and French-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr. German delegates joined the meeting, and the London Settlement was signed. It was followed by an Anglo-German commercial treaty. Another major triumph for MacDonald was the conference held in London in July and August 1924 to deal with the implementation of the Dawes Plan.[68] MacDonald, who accepted the popular view of the economist John Maynard Keynes of German reparations as impossible to pay, pressured French Premier Édouard Herriot until many concessions were made to Germany, including the evacuation of the Ruhr.[68][69]

A British onlooker commented, "The London Conference was for the French 'man in the street' one long Calvary ... as he saw M. Herriot abandoning one by one the cherished possessions of French preponderance on the Reparations Commission, the right of sanctions in the event of German default, the economic occupation of the Ruhr, the French-Belgian railroad Régie, and finally, the military occupation of the Ruhr within a year."[70] MacDonald was proud of what had been achieved, which was the pinnacle of his short-lived administration's achievements.[71] In September, he made a speech to the League of Nations Assembly in Geneva, the main thrust of which was for general European disarmament, which was received with great acclaim.[72]

MacDonald recognised the Soviet Union and MacDonald informed Parliament in February 1924 that negotiations would begin to negotiate a treaty with the Soviet Union.[73] The treaty was to cover Anglo-Soviet trade and the repayment of the British bondholders, who had lent billions to the pre-revolutionary Russian government and been rejected by the Bolsheviks. There were, in fact, two proposed treaties: one would cover commercial matters, and the other would cover a fairly vague future discussion on the problem of the bondholders. If the treaties were signed, the British government would conclude a further treaty and guarantee a loan to the Bolsheviks. The treaties were popular neither with the Conservatives nor with the Liberals, who, in September, criticised the loan so vehemently that negotiation with them seemed impossible.[74]

However, the government's fate was determined by the "Campbell Case", the abrogation of prosecuting the left-wing newspaper the Workers' Weekly for inciting servicemen to mutiny. The Conservatives put down a censure motion, to which the Liberals added an amendment. MacDonald's Cabinet resolved to treat both motions as matters of confidence. The Liberal amendment was carried, and the King granted MacDonald a dissolution of Parliament the following day. The issues that dominated the election campaign were the Campbell Case and the Russian treaties, which soon combined into the single issue of the Bolshevik threat.[75]

Zinoviev letter

On 25 October 1924, just four days before the election, the Daily Mail reported that a letter had come into its possession which purported to be a letter sent from Grigory Zinoviev, the President of the Communist International, to the British representative on the Comintern Executive. The letter was dated 15 September and so before the dissolution of parliament: it stated that it was imperative for the agreed treaties between Britain and the Bolsheviks to be ratified urgently. The letter said that those Labour members who could apply pressure on the government should do so. It went on to say that a resolution of the relationship between the two countries would "assist in the revolutionising of the international and British proletariat ... make it possible for us to extend and develop the ideas of Leninism in England and the Colonies".

The government had received the letter before its publication in the newspapers. It had protested to the Bolsheviks' London chargé d'affaires and had already decided to make public the contents of the letter with details of the official protest but it had not been swift-footed enough.[76] Historians mostly agree the Zinoviev letter was a forgery, but it closely reflected attitudes current in the Comintern.

In Opposition (1924–1929)

On 29 October 1924, the 1924 United Kingdom general election was held and the Conservative Party under Stanley Baldwin was returned decisively, gaining 155 seats for a total of 413 members of parliament. This was a landslide victory against the Liberals, who lost 118 seats (leaving them with only 40); their vote fell by over a million.

For Labour the result was a defeat not a disaster, holding on to 151 seats and losing 40. The real significance of the election was that the Liberal Party, which Labour had displaced as the second-largest political party in 1922, was now clearly the third party. Labour had put up more candidates than in 1923, and its total vote increased, suggesting that the Zinoviev letter had little effect. But for years many Labourites blamed their defeat on the Letter, through misunderstanding the political forces at work.[77][78]

Prime Minister (1929–1935)

Second term (1929–1931)

The strong majority held by the Conservatives gave Baldwin a full term during which the government had to deal with the 1926 General Strike. Unemployment remained high but relatively stable at just over 10% and, apart from 1926, strikes were at a low level.[79] At the May 1929 election, Labour won 288 seats to the Conservatives' 260, with 59 Liberals under Lloyd George holding the balance of power. MacDonald was increasingly out of touch with his supposedly safe Welsh seat at Aberavon; he largely ignored the district, and had little time or energy to help with its increasingly difficult problems regarding coal disputes, strikes, unemployment and poverty. The miners expected a wealthy man who would fund party operations, but he had no money. He disagreed with the increasingly radical activism of party leaders in the district, as well as the permanent agent, and the South Wales Mineworkers' Federation. He moved to Seaham Harbour in County Durham, a safer seat, to avoid a highly embarrassing defeat.[80][81]

Baldwin resigned and MacDonald again formed a minority government, with intermittent Liberal support. This time, MacDonald knew he had to concentrate on domestic matters. Arthur Henderson became Foreign Secretary, with Snowden again at the Exchequer. JH Thomas became Lord Privy Seal with a mandate to tackle unemployment, assisted by the young radical Oswald Mosley. Margaret Bondfield was appointed as Minister of Labour, becoming the first-ever woman cabinet minister.[82][83]

MacDonald's second government was in a stronger parliamentary position than his first, and in 1930 he was able to raise unemployment pay, pass an act to improve wages and conditions in the coal industry (i.e. the issues behind the General Strike) and pass the Housing Act 1930 which focused on slum clearances. However, an attempt by the Education Minister Charles Trevelyan to introduce an act to raise the school-leaving age to 15 was defeated by opposition from Roman Catholic Labour MPs, who feared that the costs would lead to increasing local authority control over faith schools.[65]

In international affairs, he also convened the Round Table conferences in London with the political leaders of India, at which he offered them responsible government, but not independence or even Dominion status. In April 1930 he negotiated the London Naval Treaty, limiting naval armaments, with France, Italy, Japan, and the United States.[65]

Great Depression

MacDonald's government had no effective response to the economic crisis which followed the Stock Market Crash of 1929. Philip Snowden was a rigid exponent of orthodox finance and would not permit any deficit spending to stimulate the economy, despite the urgings of Oswald Mosley, David Lloyd George and the economist John Maynard Keynes. Mosley put forward a memorandum in January 1930, calling for the public control of imports and banking as well as an increase in pensions to boost spending power. When this was repeatedly turned down, Mosley resigned from the government in February 1931 and formed the New Party. He later converted to Fascism.

By the end of 1930, unemployment had doubled to over two and a half million.[84] The government struggled to cope with the crisis and found itself attempting to reconcile two contradictory aims: achieving a balanced budget to maintain sterling on the gold standard, and maintaining assistance to the poor and unemployed, at a time when tax revenues were falling. During 1931, the economic situation deteriorated, and pressure from orthodox economists for sharp cuts in government spending increased. Under pressure from its Liberal allies, as well as the Conservative opposition who feared that the budget was unbalanced, Snowden appointed a committee headed by Sir George May to review the state of public finances. The May Report of July 1931, urged large public-sector wage cuts and large cuts in public spending, notably in payments to the unemployed, to avoid a budget deficit.[85]

National government (1931–1935)

Formation of the National Government

Although there was a narrow majority in the Cabinet for drastic reductions in spending, the minority included senior ministers such as Arthur Henderson who made it clear they would resign rather than acquiesce in the cuts. With this unworkable split, on 24 August 1931, MacDonald submitted his resignation and then agreed, on the urging of King George V, to form a National Government with the Conservatives and Liberals. With Henderson taking the lead, MacDonald, Snowden, and Thomas were quickly expelled from the Labour Party.[86] They responded by forming a new National Labour Organisation, which provided a nominal party base for the expelled MPs, but received little support in the country or the unions. Great anger in the labour movement greeted MacDonald's move. Riots took place in protest in Glasgow and Manchester. Many in the Labour Party viewed this as a cynical move by MacDonald to rescue his career, and accused him of 'betrayal'. MacDonald, however, argued that the sacrifice was for the common good.[87][88]

1931 general election

In the 1931 general election, the National Government won 554 seats, comprising 473 Conservatives, 13 National Labour, 68 Liberals (Liberal National and Liberal) and various others, while Labour, now led by Arthur Henderson won only 52 and the Lloyd George Liberals four. Henderson and his deputy J. R. Clynes both lost their seats in Labour's worst-ever rout. Labour's disastrous performance at the 1931 election greatly increased the bitterness felt by MacDonald's former colleagues towards him. MacDonald was genuinely upset to see the Labour Party so badly defeated at the election. He had regarded the National Government as a temporary measure, and had hoped to return to the Labour Party.[84]

Premiership of the National Government (1931–1935)

The National Government's huge majority left MacDonald with the largest mandate ever won by a British Prime Minister at a democratic election, but MacDonald had only a small following of National Labour men in Parliament. He was ageing rapidly, and was increasingly a figurehead. In control of domestic policy were Conservatives Stanley Baldwin as Lord President and Neville Chamberlain the chancellor of the exchequer, together with National Liberal Walter Runciman at the Board of Trade.[89] MacDonald, Chamberlain and Runciman devised a compromise tariff policy, which stopped short of protectionism while ending free trade and, at the 1932 Ottawa Conference, cementing commercial relations within the Commonwealth.[90]

Besides his preference for a cohesive British Empire and a protective tariff, he felt an independent British defence programme would be the wisest policy. However, budget pressures and a strong popular pacifist sentiment forced a reduction in the military and naval budgets.[91] MacDonald involved himself heavily in foreign policy. Assisted by the National Liberal leader and Foreign Secretary John Simon, he continued to lead British delegations to international conferences, including the Geneva Disarmament Conference and the Lausanne Conference in 1932, and the Stresa Conference in 1935.[92] He went to Rome in March 1933 to facilitate Nazi Germany's return to the concert of European powers and to continue the policy of appeasement.[93] On 16 August 1932 he granted the Communal Award upon India, partitioning it into separate electorates for Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Untouchables. Most important of all, he presided at the World Economic Conference in London in June 1933. Nearly every nation was represented, but no agreement was possible. The American president torpedoed the conference with a bombshell message that the US would not stabilise the depreciating dollar. The failure marked the end of international economic cooperation for another decade.[94]

MacDonald was deeply affected by the anger and bitterness caused by the fall of the Labour government. He continued to regard himself as a true Labour man, but the rupturing of virtually all his old friendships left him an isolated figure. One of the only other leading Labour figures to join the government, Philip Snowden, was a firm believer in free trade and resigned from the government in 1932 following the introduction of tariffs after the Ottawa agreement.[95][incomplete short citation]

Retirement

By 1933 MacDonald's health was so poor that his doctor had to personally supervise his trip to Geneva. By 1934 MacDonald's mental and physical health declined further, and he became an increasingly ineffective leader as the international situation grew more threatening. His speeches in the House of Commons and at international meetings became incoherent. One observer noted how "Things ... got to the stage where nobody knew what the Prime Minister was going to say in the House of Commons, and, when he did say it, nobody understood it". Newspapers did not report MacDonald denying to reporters that he was seriously ill because he only had "loss of memory".[65][27] His pacifism, which had been widely admired in the 1920s, led Winston Churchill and others to accuse him of failure to stand up to the threat of Adolf Hitler. His government began the negotiations for the Anglo-German Naval Agreement.

In these years he was irritated by the attacks of Lucy, Lady Houston, the strongly nationalistic proprietor of the Saturday Review. Lady Houston believed that MacDonald was under the control of the Soviets and amused the nation by giving MacDonald such epithets as the 'Spider of Lossiemouth,' and hanging a large sign in electric lights from the rigging of her luxury yacht, the SY Liberty. According to some versions, it read 'Down with Ramsay MacDonald,' and to others 'To Hell with Ramsay MacDonald.' Lady Houston also sent agents to disrupt his election campaigns. In 2020 new research revealed how she purchased three letters, supposedly written by Ramsay MacDonald to Soviet officials but actually the work of an American forger. In 1935 Lady Houston stated that she intended to publish them but eventually handed them over to Special Branch, and MacDonald's solicitors entered a legal battle with her.[96][page needed]

MacDonald was aware of his fading powers, and in 1935 he agreed to a timetable with Baldwin to stand down as Prime Minister after King George V's Silver Jubilee celebrations in May 1935. He resigned on 7 June in favour of Baldwin, and remained in the cabinet, taking the largely honorary post of Lord President vacated by Baldwin.[65]

Last years and death (1935–1937)

At the November 1935 election MacDonald was defeated at Seaham by Emanuel Shinwell, but he was re-elected to Parliament at a by-election in January 1936 for the Combined Scottish Universities seat. After Hitler's re-militarisation of the Rhineland in 1936, MacDonald declared that he was "pleased" that the Treaty of Versailles was "vanishing", expressing his hope that the French had been taught a "severe lesson".[97] MacDonald was one of the signatories to the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936.[98]

His health was failing. King George V died a week before voting began in the Scottish by-election, and MacDonald deeply mourned his death,[99][100] paying tribute to him in his diary as "a gracious and kingly friend whom I have served with all my heart".[99][100] There had been genuine affection between the two and the king is said to have regarded MacDonald as his favourite prime minister.[101][102] Following the king's death MacDonald's physical and mental health collapsed.

A sea voyage (with his youngest daughter Sheila) was recommended to restore MacDonald's health, but he died on board the liner MV Reina del Pacifico, which operated between Liverpool and Valparaíso, Chile, via the Imperial fortress colony of Bermuda, the West Indies and the Panama Canal, on 9 November 1937, aged 71.

MacDonald's body was transferred to the Royal Navy at Bermuda for return to Plymouth. All of the Bermuda-based cruisers of the America and West Indies Station were away from Bermuda at that time except for HMS Orion and HMS Apollo. As Apollo was undergoing a refit at the dockyard, it would have fallen to Orion to deliver MacDonald's body, but as she was temporary flagship since HMS York had departed on 27 October for Trinidad (due to civil unrest there) she could not leave the station and Apollo was consequently hurried through her refit instead. Orion was tasked with the memorial service for Macdonald. His body was taken aboard the Royal Navy tug Sandboy from the Reina del Pacifico and landed on Front Street in Hamilton along with the Royal Naval Dockyard Chaplain, the Orion's Chaplain, an honour guard, sentries and coffin bearers. MacDonald's coffin was borne on a gun carriage to the Church of England's Cathedral of the Most Holy Trinity, in a procession that included the ship's company of Orion and a detachment of the Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment), serving in the Bermuda Garrison. At the cathedral, Arthur Browne, the Bishop of Bermuda, conducted the memorial service, which was followed by a lying in state. Thousands visited to pay their respects. MacDonald's body and his daughter departed Bermuda the following day aboard Apollo, arriving at Plymouth on 25 November. His funeral was in Westminster Abbey on 26 November, followed by a private cremation service at Golders Green. After cremation, his ashes were taken to Lossiemouth, where a service commenced in his house, The Hillocks, followed by a procession to Holy Trinity Church, Spynie, where they were buried alongside his wife Margaret and their son David in his native Moray.[65][103][104]

Personal life

Ramsay MacDonald married Margaret Ethel Gladstone (no relation to Prime Minister William Gladstone) in 1896. The marriage was a very happy one, and they had six children, including Malcolm MacDonald (1901–81), who had a distinguished career as a politician, colonial governor and diplomat, and Ishbel (1903–82) and Sheila MacDonald, who were both very close to their father.[105] Another son, Alister Gladstone MacDonald (1898–1993) was a conscientious objector in the First World War, serving in the Friends' Ambulance Unit; he became a prominent architect who worked on promoting the planning policies of his father's government, and specialised in cinema design.[106]

MacDonald was devastated by Margaret's death from blood poisoning in 1911, and had few significant personal relationships after that time, apart from with Ishbel, who acted as his consort while he was Prime Minister and cared for him for the rest of his life. Following his wife's death, MacDonald commenced a relationship with Lady Margaret Sackville.[107]

In the 1920s and 1930s he was frequently entertained by the society hostess Lady Londonderry, which was much disapproved of in the Labour Party since her husband was a Conservative cabinet minister.[108][incomplete short citation]

MacDonald was born into a religious family, and was originally quite devout in his own beliefs. However as an adult, put off by "creeds or ritual"[109] and attracted to morality resting "upon no supernatural sanction",[110] he became an activist and a leader in the British Ethical and humanist movement. Raised in the Presbyterian church, he later joined the Free Church of Scotland as an adult "but neither creeds or ritual attracted him".[109] Subsequently, he became interested in the Unitarian movement during his time in London, and led Unitarian worship sessions. In fact, MacDonald was a passionate and prolific Unitarian preacher leading more than 500 services.[111] His Unitarianism led him to discover the Ethical movement, and he attended services at the South Place Ethical Society (now Conway Hall).[112][113][114] He became intensely involved in the Union of Ethical Societies, and friends with its founder, Stanton Coit, writing regularly in Coit's Ethical World publication.[115] On more than one occasion he took the Chair at the annual meeting of the Union of Ethical Societies. His motives are evidenced in the manifesto of the Society of Ethical Propagandists to which Macdonald was a signatory (including Coit). The manifesto stated that Ethical societies "are founded upon a conviction that the good life is desirable for its own sake, and rests upon no supernatural sanction".[110]

MacDonald's unpopularity in the country following his stance against Britain's involvement in the First World War spilled over into his private life. In 1916, he was expelled from Moray Golf Club in Lossiemouth for being deemed to bring the club into disrepute because of his pacifist views.[47] The manner of his expulsion was regretted by some members but an attempt to re-instate him by a vote in 1924 failed. However, a Special General Meeting held in 1929 finally voted for his reinstatement. By this time, MacDonald was Prime Minister for the second time. He felt the initial expulsion very deeply and refused to take up the final offer of membership, which he had framed and mounted.[116] He ultimately became a member of nearby Spey Bay Golf Club where he gifted the Club Championship trophy that is still used to this day.[117]

Reputation

| Part of a series on |

| Social democracy |

|---|

|

For half a century, MacDonald was demonised by the Labour Party as a turncoat who consorted with the enemy and drove the Labour Party to its nadir. Later, however, scholarly opinion raised his status as an important founder and leader of the Labour Party, and a man who held Britain together during its darkest economic times.[118][119]

MacDonald's expulsion from Labour along with his National Labour Organisation's coalition with the Conservatives, combined with the decline in his physical and mental powers after 1931, left him a discredited figure. The downfall of the Labour government in 1931, his National coalition with the Conservatives and the electoral defeat were blamed on him, and few spoke on his behalf.[120] MacNeill Weir, MacDonald's former parliamentary private secretary, published the first major biography The Tragedy of Ramsay MacDonald in 1938. Weir demonised MacDonald for obnoxious careerism, class betrayal and treachery.[121] Clement Attlee in his autobiography As it Happened (1954) called MacDonald's decision to abandon the Labour government in 1931 "the greatest betrayal in the political history of the country".[122] The coming of war in 1939 led to a search for the politicians who had appeased Hitler and failed to prepare Britain; MacDonald was grouped among the "Guilty Men".[123]

By the 1960s, while union activists maintained their hostile attitude, scholars wrote with more appreciation of his challenges and successes.[124] Finally in 1977 he received a long scholarly biography that historians have judged to be "definitive".[125] Labour MP David Marquand, a trained historian, wrote Ramsay MacDonald with the stated intention of giving MacDonald his due for his work in founding and building the Labour Party, and in trying to preserve peace in the years between the two world wars. He argued also to place MacDonald's fateful decision in 1931 in the context of the crisis of the times and the limited choices open to him. Marquand praised the prime minister's decision to place national interests before that of party in 1931. He also emphasised MacDonald's lasting intellectual contribution to socialism and his pivotal role in transforming Labour from an outside protest group to an inside party of government.[126]

Similarly, scholarly analysis of the economic decisions taken in the inter-war period, such as the return to the Gold Standard in 1925 and MacDonald's desperate efforts to defend it in 1931, has changed. Thus Robert Skidelsky, in his classic 1967 account of the 1929–31 government, Politicians and the Slump, compared the orthodox policies advocated by leading politicians of both parties unfavourably with the more radical, proto-Keynesian measures proposed by David Lloyd George and Oswald Mosley; subsequently, in the preface to the 1994 edition Skidelsky argued that recent experience of currency crises and capital flight made it hard to be critical of politicians who wanted to achieve stability by cutting so-called "labour costs" and defending the value of the currency.[127] In 2004 Marquand advanced a similar argument:

In the harsher world of the 1980s and 1990s it was no longer obvious that Keynes was right in 1931 and the bankers wrong. Pre-Keynesian orthodoxy had come in from the cold. Politicians and the public had learned anew that confidence crises feed on themselves; that currencies can collapse; that the public credit can be exhausted; that a plummeting currency can be even more painful than deflationary expenditure cuts; and that governments which try to defy the foreign exchange markets are apt to get their—and their countries'—fingers burnt. Against that background, MacDonald's response to the 1931 crisis increasingly seemed not just honourable and consistent, but right ... he was the unacknowledged precursor of the Blairs, the Schröders, and the Clintons of the 1990s and 2000s.[128]

Cultural depictions

Honours

In 1930, MacDonald was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) under Statute 12.[129] He was awarded honorary Doctor of Laws (LLD) degrees by the universities of Wales, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Oxford and McGill and George Washington University.[130]

References

- ^ "James Ramsay MacDonald".

- ^ Shepherd 2007, pp. 31–.

- ^ Marquand 1977, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 6.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 5.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 12.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 15.

- ^ Bryher, Samual: An Account of the Labour and Socialist Movement in Bristol, 1929

- ^ Elton 1939, p. 44.

- ^ Marquand 1977, pp. 9, 17.

- ^ Tracey, Herbert: J. Ramsay MacDonald, 1924, p. 29

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 20.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 21.

- ^ Morgan, J. Ramsay MacDonald (1987) p. 17

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 23.

- ^ MacDonald, James Ramsay (1921). Socialism: critical and constructive. Cassell's social economics series. Cassell and Company Ltd.

- ^ Elton 1939, pp. 56–57.

- ^ "Letter from Ramsay McDonald to Birkbeck College – Birkbeck, University of London". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ Conor Cruise O' Brien, Parnell and his Party, 1957, p. 275

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 22.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 31.

- ^ Dover Express, 17 June 1892; 12 August 1892

- ^ Dover Express, 7 October 1892

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 35.

- ^ Southampton Times, 21 July 1894

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 73.

- ^ a b Gunther, John (1940). Inside Europe. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 335, 337–340.

- ^ Jennings 1962, p. 457.

- ^ Mackintosh, John P. (Ed.): British Prime Ministers in the twentieth Century, London, 1977, p. 157

- ^ MacDonald Papers, P.R.O. 3/95

- ^ McDonald, Deborah, Clara Collet 1860–1948: An Educated Working Woman; Routledge: 2004

- ^ Diary of Clara Collet: Warwick Modern Records Office

- ^ Morgan 1987, p. 30.

- ^ Clegg, H.A;, Fox, Alan; Thompson, A.F.: A History of British Trade Unions since 1889, 1964, vol I, p. 388

- ^ Leicester Pioneer, 20 January 1906

- ^ Morgan 1987, p. 40.

- ^ Kenneth Morgan (1987) pp 42–43

- ^ Thompson, Laurence: The Enthusiasts, (1971), p. 173

- ^ Marquand 1977, pp. 77, 168.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 168.

- ^ "HC Deb 03 August 1914 vol 65 c. 1831".

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 169.

- ^ MacKintosh, John P (Ed.): British Prime Ministers in the Twentieth Century, (1977), p. 159.

- ^ Elton 1939, pp. 269–271.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 189.

- ^ Symons, Julian, Horatio Bottomley, Cressett Press, London, 1955, pp. 168–169

- ^ a b Marquand 1977, pp. 190, 191.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 192.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 205.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 236.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 250.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 273.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 274.

- ^ Marquand 1977, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 283.

- ^ Kenneth Morgan (1987) pp. 44–45

- ^ a b c David Cesarani. "Anti-Zionism in Britain, 1922–2002: Continuities and Discontinuities" The Journal of Israeli History 25.1 (2006): 141

- ^ Neilson, Keith; Otte, T.G. (2008). The Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, 1854–1946. New York: Routledge. p. 175. ISBN 978-1134231393.

- ^ a b Bennett, Gill (22 January 2014). "What's the context? 22 January 1924: Britain's first Labour government takes office – History of government – What's the context? series". history.blog.gov.uk. The National Archives of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

Ramsay MacDonald took office as both Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary of a minority government on 22 January 1924.

- ^ a b "Scotland Back in the Day: Remembering the first working-class PM, Ramsay MacDonald, 150 years after his birth", The National.

- ^ "Ramsay MacDonald", Spartacus Educational, John Simkin, September 1997 (updated February 2016).

- ^ Taylor 1965, p. 209.

- ^ Sir Harold Nicolson, King George V: His life and reign (1952)

- ^ Taylor 1965, pp. 213–214.

- ^ a b c d e f Morgan, Kevin. (2006) MacDonald (20 British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century), Haus Publishing, ISBN 1904950612

- ^ Keith Robbins, "Labour Foreign Policy and International Socialism: MacDonald and the League of Nations," in Robbins, Politicians, Diplomacy and War (2003) pp. 239–272

- ^ Marquand 1977, pp. 315–317.

- ^ a b Marks, Sally (1978). "The Myths of Reparations". Central European History. 11 (3): 231–255. doi:10.1017/s0008938900018707. S2CID 144072556.

- ^ Steiner, Zara (2005). The lights that failed : European international history, 1919–1933. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0191518812. OCLC 86068902.

- ^ Marks, "The Myths of Reparations", p. 249

- ^ Marquand 1977, pp. 329–351.

- ^ Limam: The First Labour Government, 1924, p. 173

- ^ Curtis Keeble (1990). Britain and the Soviet Union 1917–89. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 117. ISBN 978-1349206438.

- ^ Lyman, The First Labour Government, 1924 pp. 195–204

- ^ A.J.P. Taylor (1965). English History, 1914–1945. Clarendon Press. pp. 217–20, 225–226. ISBN 978-0198217152.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 382.

- ^ Taylor 1965, pp. 219–220, 226–227.

- ^ C. L. Mowat (1955). Britain Between the Wars, 1918–1940. Taylor & Francis. pp. 188–194.

- ^ "A Century of Change: Trends in UK statistics since 1900," Research Paper 99/111, 1999, House of Commons Library

- ^ "Mr. W. G. Covr, M.P., May Not Stand Again at Wellingborough". Northampton Mercury. 17 August 1928. Retrieved 25 October 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Chris Howard, "Ramsay MacDonald and Aberavon, 1922–29," Llafur: Journal of Welsh Labour History 7#1 (1996) pp. 68–77

- ^ John Shepherd, The Second Labour Government: A reappraisal (2012).

- ^ "The New Ministry". Hartlepool Mail. 8 June 1929. Retrieved 25 October 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b Davies, A.J. (1996) To Build A New Jerusalem: The British Labour Party from Keir Hardie to Tony Blair, Abacus, ISBN 0349108099

- ^ C. L. Mowat, Britain between the Wars, 1918–1940 (1955) pp. 379–401

- ^ Andrew Thorpe, "Arthur Henderson and the British political crisis of 1931." Historical Journal 31#1 (1988): 117–139.

- ^ Martin Pugh Speak for Britain!: A New History of the Labour Party (2010) pp. 212–216

- ^ Reginald Bassett, 1931 Political Crisis (MacMillan, 1958) defends MacDonald.

- ^ Harford Montgomery Hyde (1973). Baldwin; the unexpected Prime Minister. Hart-Davis MacGibbon. p. 345. ISBN 978-0246640932.

- ^ Wrench, David (2000). "'Very Peculiar Circumstances': Walter Runciman and the National Government, 1931–3". Twentieth Century British History. 11 (1): 61–82. doi:10.1093/tcbh/11.1.61.

- ^ Taylor 1965, pp. 359–370.

- ^ Kevin Morgan (2006). Ramsay MacDonald. Haus Publishing. p. 79. ISBN 978-1904950615.

- ^ Aage Trommer, "MacDonald in Geneva in March 1933: A study in Britain's European policy." Scandinavian Journal of History 1#1–4 (1976): 293–312.

- ^ Taylor 1965, pp. 334–335.

- ^ Morgan 1987, p. 213.

- ^ Crompton, Teresa (2020). Adventuress, the Life and Loves of Lucy, Lady Houston. The History Press.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Stevenson, David (1998). "France at the Paris Peace Conference: Addressing the Dilemmas of Security". In Robert W. D. Boyce (ed.). French Foreign and Defence Policy, 1918–1940: The Decline and Fall of a Great Power. London: Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 978-0415150392.

- ^ "Historic Anglo-Egyptian treaty signed in London – archive, 1936". Guardian. 27 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ a b Marquand 1977, p. 784 "George V's death in January 1936, had been a heavy blow to MacDonald; it is clear from his diary that he must have taken some time to recover from it."

- ^ a b Morgan 1987, p. 234.

- ^ Berkeley, Humphry (1978). The myth that will not die: the formation of the National Government 1931. Croom Helm. p. 15. ISBN 978-0856647734.

- ^ Watkins, Alan (2 September 1978). "History without heroes". The Spectator. Vol. 241. F.C. Westley. p. 20.

- ^ "Ramsay MacDonald's Last Homecoming: Bermuda to Lossiemouth". The Illustrated London News. London. 4 December 1937.

- ^ H.M.S. Orion 1937–1939. Flood & Son, Ltd, The Borough Press, Lowestoft: Royal Navy (HMS Orion). 1939. p. 26.

- ^ Lyon, Peter (23 September 2004). "MacDonald, Malcolm John (1901–1981), politician and diplomatist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1 (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31388. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ David Goold (2008). "Alister Gladstone MacDonald (or Alistair Gladstone MacDonald)". Dictionary of Scottish Architects. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ Fenton, Ben (2 November 2006). "Secret love affair of Labour Prime Minister and Lady Margaret is revealed 80 years on". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ Morgan 1987, p. 124.

- ^ a b Elton 1939, p. 38.

- ^ a b Elton 1939, p. 94.

- ^ Tom McReady (2015) Blessed is the Peacemaker: The Religious Vision of Ramsay MacDonald. Richmond and Putney Unitarian Church.

- ^ Marquand 1977, p. 24.

- ^ Turner, Jacqueline (2018). The Labour Church: Religion and Politics in Britain 1890–1914. I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd.

- ^ Hunt, James D. (2005). An American Looks at Gandhi: Essays in Satyagraha, Civil Rights, and Peace. Promilla & Co Publishers Ltd.

- ^ Roger E Backhouse; Tamotsu Nishizawa, eds. (2010). No Wealth But Life: Welfare Economics and the Welfare State in Britain, 1880–1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0521197861.[dead link]

- ^ McConnachie, John. The Moray Golf Club at Lossiemouth, 1988

- ^ "Spey Bay Golf Club". Moray Speyside Golf. 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Shepherd 2007, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Owen, Nicholas (2007). "MacDonald's Parties: The Labour Party and the 'Aristocratic Embrace' 1922–31". Twentieth Century British History. 18 (1): 1–53. doi:10.1093/tcbh/hwl043.

- ^ Marquand 2004, p. 700.

- ^ Martin 2003, pp. 836–837.

- ^ Clement Attlee, As it Happened. Heinemann: 1954

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Martin 2003, pp. 836–837; Shepherd 2007, pp. 31–33.

- ^ David Dutton (2008). Liberals in Schism: A History of the National Liberal Party. I.B. Tauris. p. 88. ISBN 978-0857737113.

- ^ Martin 2003, p. 837.

- ^ Robert Skidelsky (1994). Politicians and the slump: The Labour Government of 1929–1931. Papermac. ISBN 978-0333605929.

- ^ Marquand 2004.

- ^ Gregory, R. A. (1939). "James Ramsay MacDonald. 1866–1937". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 2 (7): 475–482. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1939.0007.

- ^ "MacDonald, Rt Hon. James Ramsay, (12 October 1866 – 9 November 1937), JP Morayshire; MP (Lab.) Aberavon Division of Glamorganshire, 1922–29, Seaham Division Co. Durham, 1929–31, (Nat. Lab.) 1931–35, Scottish Universities since 1936". MacDonald, Rt Hon. James Ramsay. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2007. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U213229.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)

Bibliography

- Barker, Rodney. "Political Myth: Ramsay MacDonald and the Labour Party." History 61.201 (1976): 46–56. online

- Byrne, Christopher, Nick Randall, and Kevin Theakston. "Disjunctive Leadership in Interwar Britain: Stanley Baldwin, Ramsay MacDonald, and Neville Chamberlain." in Disjunctive Prime Ministerial Leadership in British Politics (Palgrave Pivot, Cham, 2020) pp. 17–49.

- Carlton, David. MacDonald versus Henderson: The Foreign Policy of the Second Labour Government (2014).

- Eccleshall, Robert, and Graham Walker, eds. Biographical Dictionary of British Prime Ministers (1998) pp. 281–288. online

- Elton, Lord (1939). The Life of James Ramsay MacDonald (1866–1919. Collins. ISBN 978-1406730456.

- Heppell, Timothy, and Kevin Theakston, eds. How Labour Governments Fall: From Ramsay MacDonald to Gordon Brown (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

- Hinks, John Ramsay MacDonald: the Leicester years (1906–1918), Leicester, 1996

- Howard, Christopher. "MacDonald, Henderson, and the Outbreak of War, 1914." Historical Journal 20.4 (1977): 871–891. online

- Howell, David MacDonald's Party. Labour Identities and Crisis, 1922–1931, Oxford: OUP 2002; ISBN 0198203047

- Jennings, Ivor (1962). Party Politics: Volume 3, The Stuff of Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521054348.

- Kitching, Carolyn J. "Prime minister and foreign secretary: the dual role of James Ramsay MacDonald in 1924." Review of International Studies 37#3 (2011): 1403–1422. online

- Lloyd, Trevor. "Ramsay MacDonald: Socialist or Gentleman?." Canadian Journal of History/Annales Canadiennes d'Histoire 15#3 (1980) online Archived 8 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Lyman, Richard W. The First Labour Government, 1924 (Chapman & Hall, 1957). online free to borrow

- Lyman, Richard W. "James Ramsay MacDonald and the Leadership of the Labour Party, 1918–22." Journal of British Studies 2#1 (1962): 132–160. online

- Martin, David E. (2003). "MacDonald, (James) Ramsay". In Loades, David (ed.). Reader's Guide to British History. Vol. 2.

- McKibbin, Ross I. "James Ramsay MacDonald and the Problem of the Independence of the Labour Party, 1910–1914." Journal of Modern History 42#2 (1970): 216–235. in JSTOR

- Marquand, David (1977). Ramsay MacDonald. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0224012959.; 902pp

- Marquand, David (2004). "MacDonald, (James) Ramsay (1866–1937)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34704; (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) online edn, Oct 2009 accessed 9 Sept 2012

- Morgan, Austen (1987). J. Ramsay MacDonald. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719021688.

- Morgan, Kenneth O. Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants Hardy to Kinnock (1987) pp. 39–53. online free to borrow

- Morgan, Kevin. Ramsay MacDonald (2006) online free to borrow

- Mowat, C. L. "Ramsay MacDonald and the Labour Party," in Essays in Labour History 1886–1923, edited by Asa Briggs, and John Saville, (1971)

- Mowat, Charles L. "The Fall of the Labour Government in Great Britain, August, 1931," Huntington Library Quarterly 7#4 (1944), pp. 353–386 JSTOR 3815737

- Mowat, Charles Loch. Britain between the Wars: 1918–1945 (1955) PP 413–79

- Owen, Nicholas (2007). "MacDonald's Parties: The Labour Party and the 'Aristocratic Embrace' 1922–31". Twentieth Century British History. 18 (1): 1–53. doi:10.1093/tcbh/hwl043.

- Phillips, Gordon: The Rise of the Labour Party 1893–1931, (Routledge 1992).

- Riddell, Neil. Labour in Crisis: The Second Labour Government, 1929–31 (1999).

- Robbins, Keith (1994). Politicians, Diplomacy and War in Modern British History. A&C Black. pp. 239–272. ISBN 978-0826460479.

- Rosen, Greg (ed.) Dictionary of Labour Biography, London: Politicos Publishing 2001; ISBN 978-1902301181

- Rosen, Greg (ed.) Old Labour to New. The Dreams That Inspired, the Battles That Divided (London: Politicos Publishing 2005; ISBN 978-1842750452).

- Sacks, Benjamin. J. Ramsay MacDonald in Thought and Action (University of New Mexico Press, 1952), favourable biography by American scholar

- Shepherd, John and Keith Laybourn. Britain's First Labour Government (2006).

- Shepherd, John. The Second Labour Government: A reappraisal (2012).

- Skidelsky, Robert. Politicians and the Slump: The Labour Government of 1929–1931 (1967).

- Smart, Nick. The National Government. 1931–40 (Macmillan 1999) ISBN 0-333-69131-8

- Stewart, John. "Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Party, and child welfare, 1900–1914." Twentieth Century British History 4.2 (1993): 105–125.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1965). English History: 1914–1945.

- Thorpe, Andrew. "Arthur Henderson and the British political crisis of 1931." Historical Journal 31#1 (1988): 117–139, On the expulsion of MacDonald from the Labour Party.

- Thorpe, Andrew Britain in the 1930s. The Deceptive Decade (Blackwell 1992; ISBN 0631174117)

- Ward, Stephen R. James Ramsay MacDonald: Low Born among the High Brows (1990).

- Weir, L. MacNeill. The Tragedy of Ramsay MacDonald: A Political Biography (1938). Highly influential and extremely negative account by a former aide. online

- Williamson, Philip: National Crisis and National Government. British Politics, the Economy and the Empire, 1926–1932, Cambridge: CUP 1992; ISBN 0521361370

- Wrigley, Chris. "James Ramsay MacDonald 1922–1931," in Leading Labour: From Keir Hardie to Tony Blair, edited by Kevin Jefferys, (1999)

Historiography

- Callaghan, John, et al. eds. Interpreting the Labour Party: Approaches to Labour Politics and History (2003) online

- Loades, David, ed. Reader's Guide to British History (2003) 2:836–837.

- Shepherd, John (November 2007). "The Lad from Lossiemouth". History Today. Vol. 57, no. 11. pp. 31–33.

Primary sources

- Barker, Bernard (ed.) Ramsay MacDonald's Political Writings (Allen Lane, 1972).

- Cox, Jane A Singular Marriage: A Labour Love Story in Letters and Diaries (of Ramsay and Margaret MacDonald), London: Harrap 1988; ISBN 978-0245546761

- MacDonald, Ramsay The Socialist Movement (1911) online; free copy

- MacDonald, Ramsay Socialism and Society (1914) online

- MacDonald, Ramsay. Labour and Peace, Labour Party 1912

- MacDonald, Ramsay. Parliament and Revolution, Labour Party 1919

- MacDonald, Ramsay. Parliament and revolution (1920) online

- MacDonald, Ramsay. Foreign Policy of the Labour Party, Labour Party 1923

- MacDonald, Ramsay. Margaret Ethel MacDonald (1924) online

- MacDonald, Ramsay. Socialism: critical and constructive (1924) online

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Ramsay MacDonald

- Ramsay MacDonald – 1924 First Labour Government – UK Parliament Living Heritage

- A left-wing criticism of Macdonald's career Archived 27 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine Socialist Review

- More about Ramsay MacDonald Prime Minister's Office

- Ramsay MacDonald Papers, 1893–1937

- Portraits of Ramsay MacDonald at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- "Archival material relating to Ramsay MacDonald". UK National Archives.

- Newspaper clippings about Ramsay MacDonald in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW