Pyu language (Sino-Tibetan)

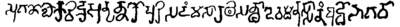

| Pyu | |

|---|---|

| Tircul | |

Pyu alphabet | |

| Region | Pyu city-states, Pagan Kingdom |

| Extinct | 13th century |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Pyu script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | pyx |

pyx | |

| Glottolog | burm1262 |

The Pyu language (Pyu: ![]() ; Burmese: ပျူ ဘာသာ, IPA: [pjù bàðà]; also Tircul language) is an extinct Sino-Tibetan language that was mainly spoken in what is now Myanmar in the first millennium CE. It was the vernacular of the Pyu city-states, which thrived between the second century BCE and the ninth century CE. Its usage declined starting in the late ninth century when the Bamar people of Nanzhao began to overtake the Pyu city-states. The language was still in use, at least in royal inscriptions of the Pagan Kingdom if not in popular vernacular, until the late twelfth century. It became extinct in the thirteenth century, completing the rise of the Burmese language, the language of the Pagan Kingdom, in Upper Burma, the former Pyu realm.[1]

; Burmese: ပျူ ဘာသာ, IPA: [pjù bàðà]; also Tircul language) is an extinct Sino-Tibetan language that was mainly spoken in what is now Myanmar in the first millennium CE. It was the vernacular of the Pyu city-states, which thrived between the second century BCE and the ninth century CE. Its usage declined starting in the late ninth century when the Bamar people of Nanzhao began to overtake the Pyu city-states. The language was still in use, at least in royal inscriptions of the Pagan Kingdom if not in popular vernacular, until the late twelfth century. It became extinct in the thirteenth century, completing the rise of the Burmese language, the language of the Pagan Kingdom, in Upper Burma, the former Pyu realm.[1]

The language is principally known from inscriptions on four stone urns (7th and 8th centuries) found near the Payagyi pagoda (in the modern Bago Township) and the multi-lingual Myazedi inscription (early 12th century).[2][3] These were first deciphered by Charles Otto Blagden in the early 1910s.[3]

The Pyu script was a Brahmic script. Recent scholarship suggests the Pyu script may have been the source of the Burmese script.[4]

Classification

Blagden (1911: 382) was the first scholar to recognize Pyu as an independent branch of Sino-Tibetan.[5] Miyake (2021, 2022) argues that Pyu forms a branch of its own within the Sino-Tibetan language phylum due to its divergent phonological and lexical characteristics. Pyu is not a particularly conservative Sino-Tibetan language, as it displays many phonological and lexical innovations as has lost much of the original Proto-Sino-Tibetan morphology.[6][7] Miyake (2022) suggests that this may be due to a possible creoloid origin of Pyu.[8]

Pyu was tentatively classified within the Lolo-Burmese languages by Matisoff and thought to most likely be Luish by Bradley, although Miyake later showed that neither of these hypotheses are plausible. Van Driem also tentatively classified Pyu as an independent branch of Sino-Tibetan.[9]

Phonology

Marc Miyake reconstructs the syllable structure of Pyu as:[6]

- (C.)CV(C)(H)

- (preinitial) + syllable

7 vowels are reconstructed.[6]

| front | mid | back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| high | i | u | |

| mid | e | ə | o |

| low | æ | a |

Miyake reconstructs 43-44 onsets, depending on whether or not the initial glottal stop is included. Innovative onsets are:[6]

- fricatives: /h ɣ ç ʝ ð v/

- liquids: /R̥ R L̥ L/

- implosive: /ɓ/

10 codas are reconstructed, which are -k, -t, -p, -m, -n, -ŋ, -j, -r, -l, -w. Pyu is apparently isolating, with no inflection morphology observed.[6]

List of Pyu inscriptions

| Location | Inventory number |

|---|---|

| Halin | 01[10] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 04[11] |

| Pagan | 07[12] |

| Pagan | 08[13] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 10[14] |

| Pagan | 11[15] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 12[16] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 22[17] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 25[18] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 28[19] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 29[20] |

| Myittha | 32[21] |

| Myittha | 39[22] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 42[23] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 55[24] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 56[25] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 57[26] |

| Halin | 60[27] |

| Halin | 61[28] |

| ??? | 63[29] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 105[30] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 160[31] |

| ??? | 163[32] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 164[33] |

| Śrī Kṣetra | 167[34] |

Vocabulary

Below are selected Pyu basic vocabulary items from Gordon Luce and Marc Miyake.

| Gloss | Luce (1985)[35] | Miyake (2016)[36] | Miyake (2021)[6] |

|---|---|---|---|

| one | tå | ta(k·)ṁ | /tæk/ |

| two | hni° | kni | |

| three | ho:, hau: | hoḥ | /n.homH/ < *n.sumH < *məsumH |

| four | pḷå | plaṁ | |

| five | pi°ŋa | (piṁ/miṁ) ṅa | /pəŋa/ |

| six | tru | tru(k·?) | |

| seven | kni | hni(t·?)ṁ | |

| eight | hrå | hra(t·)ṁ | |

| nine | tko | tko | /t.ko/ |

| ten | sū, sau | su | |

| twenty | tpū | ||

| bone, relic | ru | ||

| water | tdu̱- | /t.du/ | |

| gold | tha | ||

| day | phru̱ | ||

| month | de [ḷe ?] | ||

| year | sni: | ||

| village | o | ||

| good; well | ha | ||

| to be in pain, ill | hni°: | ||

| nearness | mtu | ||

| name | mi | /r.miŋ/ | |

| I | ga°: | ||

| my | gi | ||

| wife | maya: | ||

| consort, wife | [u] vo̱: | ||

| child, son | sa: | /saH/ | |

| grandchild | pli, pli° | ||

| give | /pæH/ |

Sound changes

Pyu displays the following sound changes from Proto-Tibeto-Burman.[6]

- sibilant chain shift: *c > *s > /h/

- denasalization: *m > /ɓ/ and possibly *ŋ > /g/

- *e-lowering: *e > /ä/

- *sC-cluster compression: *sk, *st, *sp > /kʰ, tʰ, pʰ/

Usage

The language was the vernacular of the Pyu states. However, Sanskrit and Pali appeared to have co-existed alongside Pyu as the court language. The Chinese records state that the 35 musicians that accompanied the Pyu embassy to the Tang court in 800–802 played music and sang in the Fàn (梵 "Sanskrit") language.[37]

| Pyu Pali | Burmese Pali | Thai Pali | Translation[38] |

|---|---|---|---|

(Pyu alphabet AD 500 to 600 Writings) |

ဣတိပိ သော ဘဂဝါ အရဟံ သမ္မာသမ္ဗုဒ္ဓော ဝိဇ္ဇာစရဏသမ္ပန္နော |

อิติปิ โส ภควา อรหํ สมฺมาสมฺพุทฺโธ วิชฺชาจรณสมฺปนฺโน | Thus, indeed is that Gracious One: The Worthy One, fully enlightened, endowed with clear vision and virtuous conduct, |

|

သုဂတော လောကဝိဒူ အနုတ္တရော ပုရိသဒမ္မ သာရထိ သတ္ထာ ဒေဝမနုသာနံ ဗုဒ္ဓေါ ဘဂဝါ(တိ) | สุคโต โลกวิทู อนุตฺตโร ปุริสทมฺมสารถิ สตฺถาเทวมนุสฺสานํ พุทฺโธ ภควา(ติ) | sublime, the Knower of the worlds, the unsurpassed guide of those who need taming, the Teacher of gods and men, the Buddha and the Gracious One. |

Notes

- ^ Htin Aung (1967), pp. 51–52.

- ^ Blagden, C. Otto (1913–1914). "The 'Pyu' inscriptions". Epigraphia Indica. 12: 127–132.

- ^ a b Beckwith, Christopher I. (2002). "A glossary of Pyu". In Beckwith, Christopher I. (ed.). Medieval Tibeto-Burman languages. Brill. pp. 159–161. ISBN 978-90-04-12424-0.

- ^ Aung-Thwin (2005), pp. 167–177.

- ^ Blagden (1911).

- ^ a b c d e f g Miyake, Marc (June 1, 2021a). "The Prehistory of Pyu". doi:10.5281/zenodo.5778089.

• "The Prehistory of Pyu - Marc Miyake - SEALS 2021 KEYNOTE TALK". Retrieved 2022-12-25 – via YouTube. - ^ Miyake (2021), p. [page needed].

- ^ Miyake, Marc (2022-01-28). Alves, Mark; Sidwell, Paul (eds.). "The Prehistory of Pyu". Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society: Papers from the 30th Conference of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society (2021). 15 (3): 1–40. hdl:10524/52498. ISSN 1836-6821.[verification needed]

- ^ van Driem, George. "Trans-Himalayan Database". Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU001) held at the Archaeological Museum at Halin [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.579711

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU004) around a funerary urn held by the Śrī Kṣetra museum [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.581381

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of the quadrilingual Pyu inscription (PYU007) kept in an inscription shed on the grounds of the Myazedi pagoda in Pagan [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.579873

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of the quadrilingual Pyu inscription (PYU008) held at the Pagan museum, originally found in the grounds of the Myazedi pagoda [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/10.5281/zenodo.580158

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU010) kept in one of two inscription sheds on the grounds of the Śrī Kṣetra museum [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.580597

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a bilingual Pyu inscription (PYU011) held at the Pagan museum [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.580282

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Sanskrit-Pyu bilingual inscription (PYU012) around the base of a Buddha statue held by the Śrī Kṣetra museum [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.581383

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU022) held by the Śrī Kṣetra museum [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.581468

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU025) on the base of a funerary urn held at the Śrī Kṣetra museum [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.580777

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU028) kept in one of two inscription sheds on the grounds of the Śrī Kṣetra museum [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.580791

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU029) kept in one of two inscription sheds on the grounds of the Śrī Kṣetra museum [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.581217

- ^ Miles, James, & Hill, Nathan W. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscriptions (PYU032) kept in an inscription shed on the grounds of a pagoda in Myittha [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.579848

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU039) kept in an inscription shed on the grounds of a monastery in Myittha [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.579725

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU042) kept in one of two inscription sheds on the grounds of the Śrī Kṣetra museum [Data set]. . Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.581251

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU055) held by the Śrī Kṣetra museum [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.806133

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU056) held by the Śrī Kṣetra museum [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.806148

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU057) held by the Śrī Kṣetra museum [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.806163

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscriptions (PYU060) kept in the inscription shed outside the Archaeological Museum at Halin [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.579695

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscriptions (PYU061) held at the Archaeological Museum at Halin [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.579710

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU063) held at the National Museum (Burmese: အမျိုးသား ပြတိုက်) in Rangoon [Data set]. Zenodo. http://doi.org/ doi:10.5281/zenodo.806174

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription on a gold ring (PYU105) held by the Śrī Kṣetra museum [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.806168

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU160) discovered in Śrī Kṣetra [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.823725

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU163) [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.825673

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU164) [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.825685

- ^ Miles, James. (2016). Documentation of a Pyu inscription (PYU167) [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.823753

- ^ Luce, George. 1985. Phases of Pre-Pagan Burma: languages and history (volume 2). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-713595-1. pp. 66–69.

- ^ Miyake, Marc. 2016. Pyu numerals in comparative perspective. Presentation given at SEALS 26.

- ^ Aung-Thwin (2005), pp. 35–36.

- ^ "Pali chant with English translation" (PDF). Tufts University Chaplaincy. Retrieved Feb 8, 2022.

References

- Aung-Thwin, Michael (2005). The mists of Rāmañña: The Legend that was Lower Burma (illustrated ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2886-8.

- Blagden, C. Otto (1911). "A preliminary study of the fourth text of the Myazedi inscriptions". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. 43 (2): 365–388. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00041526. S2CID 163623038.

- Htin Aung, Maung (1967). A History of Burma. New York and London: Cambridge University Press.

- Miyake, Marc (2021). The Pyu Language of Ancient Burma. Beyond Boundaries. Vol. 6. De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110656442.

Further reading

- Griffiths, Arlo; Hudson, Bob; Miyake, Marc; Wheatley, Julian K. (2017). "Studies in Pyu Epigraphy, I: State of the Field, Edition and Analysis of the Kan Wet Khaung Mound Inscription, and Inventory of the Corpus". Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. 103: 43–205. doi:10.3406/befeo.2017.6247.

- Griffiths, Arlo, Marc Miyake & Julian K. Wheatley. 2021. Corpus of Pyu inscriptions.

- Harvey, G. E. (1925). History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Miyake, Marc (2018). "Studies in Pyu Phonology, ii: Rhymes". Bulletin of Chinese Linguistics. 11 (1–2): 37–76. doi:10.1163/2405478X-01101008.

- Miyake, Marc (2019). "A first look at Pyu grammar". Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 42 (2): 150–221. doi:10.1075/ltba.18013.miy. S2CID 213553247.

- Shafer, Robert (1943). "Further analysis of the Pyu inscriptions". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 7 (4): 313–366. doi:10.2307/2717831. JSTOR 2717831.

External links

- The Pre-History of Pyu, Marc Miyake

- Searchable corpus of Pyu inscriptions

- Datasets for Pyu inscriptions, photographed by James Miles