Pyongyang

Pyongyang 평양시 | |

|---|---|

| Pyongyang Directly Governed City | |

| transcription(s) | |

| • Chosŏn'gŭl | 평양직할시 |

| • Hancha | 平壤直轄市 |

| • McCune–Reischauer | P'yŏngyang Chikhalsi |

| • Revised Romanization | Pyeongyang Jikhalsi |

| Nickname(s): | |

Location of Pyongyang in North Korea | |

Pyongyang highlighted in red in North Korea | |

| Coordinates: 39°01′00″N 125°44′51″E / 39.01667°N 125.74750°E | |

| Country | North Korea |

| Districts | 19 districts(or wards), 2 counties,1 neighbourhood

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Directly governed city |

| • Body | Pyongyang City People's Assembly |

| • Secretary of the City Committee | Kim Su-gil |

| • Chairman of the People's Committee | Choi Hee-tae |

| Area | |

| 829.1 km2 (320.1 sq mi) | |

| • Metro | 3,194 km2 (1,233 sq mi) |

| Population (2021)[3] | |

| 3,157,538 | |

| • Density | 3,800/km2 (9,900/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Pyongyangite(s)[4] |

| Time zone | UTC+09:00 (Pyongyang Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | (Not Observed) |

| ISO 3166 code | KP-01 |

| Pyongyang | |

"Pyongyang" in Chosŏn'gŭl (top) and hancha (bottom) | |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Chosŏn'gŭl | 평양 |

| Hancha | 平壤 |

| Revised Romanization | Pyeongyang |

| McCune–Reischauer | P'yŏngyang |

| lit. 'flat soil' | |

Pyongyang[a] (Korean: 평양; Hancha: 平壤) is the capital and largest city of North Korea, where it is sometimes labeled as the "Capital of the Revolution" (혁명의 수도).[8] Pyongyang is located on the Taedong River about 109 km (68 mi) upstream from its mouth on the Yellow Sea. According to the 2008 population census, it has a population of 3,255,288.[9] Pyongyang is a directly administered city (직할시; 直轄市; chikhalsi) with a status equal to that of the North Korean provinces.

Pyongyang is one of the oldest cities in Korea.[10] It was the capital of two ancient Korean kingdoms, Gojoseon and Goguryeo, and served as the secondary capital of Goryeo. Following the establishment of North Korea in 1948, Pyongyang became its de facto capital. The city was again devastated during the Korean War, but was quickly rebuilt after the war with Soviet assistance.

Pyongyang is the political, industrial and transport center of North Korea. It is estimated that 99% of those living in Pyongyang are members, candidate members, or dependents of members of the ruling Workers' Party of Korea (WPK).[11] It is home to North Korea's major government institutions, as well as the WPK which has its headquarters in the so-called Forbidden City.

Names

The name Pyongyang is borrowed from Korean "평양" (literally "flat land"), from McCune–Reischauer (MR) romanisation P'yŏngyang, a Sino-Korean word from 平壤. It indicates the geographical feature of the location to have a smooth terrain. In native Korean, the city was called "Buruna" (부루나)[12] or less commonly "Barana" (바라나)[13] which, using the idu system, was the pronunciation of the Chinese characters of "Pyongyang".[12][13] "Buru" (부루) means "field" whereas "na" (나) means "land", therefore the meaning of Pyongyang in native Korean would be "Land of the field".[12]

The city's other historic names include Ryugyong,[14] Kisong, Hwangsong, Rakrang, Sŏgyong, Sodo, Hogyong, Changan,[15] and Heijō[16][17] (during Japanese rule in Korea). There are several variants.[b][32] During the early 20th century, Pyongyang came to be known among missionaries as being the "Jerusalem of the East", due to its historical status as a stronghold of Christianity, namely Protestantism, especially during the Pyongyang Revival of 1907.[33][34]

After Kim Il Sung's death in 1994, some members of Kim Jong Il's faction proposed changing the name of Pyongyang to "Kim Il Sung City" (Korean: 김일성시; Hanja: 金日成市), but others suggested that North Korea should begin calling Seoul "Kim Il Sung City" instead and grant Pyongyang the moniker "Kim Jong Il City". In the end, neither proposal was implemented.[35]

History

Prehistory

In 1955, archaeologists excavated evidence of prehistoric dwellings in a large ancient village in the Pyongyang area, called Kŭmtan-ni, dating to the Jeulmun and Mumun pottery periods.[36] North Koreans associate Pyongyang with the mythological city of "Asadal", or Wanggeom-seong, the first second millennium BC capital of Gojoseon ("Old Joseon") according to Korean historiographies beginning with the 13th-century Samguk yusa.

Historians[who?] deny this claim because earlier Chinese historiographical works such as the Guanzi, Classic of Mountains and Seas, Records of the Grand Historian, and Records of the Three Kingdoms, mention a much later "Joseon".[citation needed] The connection between the two therefore may have been asserted by North Korea for the use of propaganda.[citation needed] Nevertheless, Pyongyang became a major city in old Joseon.

Historical period

Pyongyang was founded in 1122 BC on the site of the capital of the legendary king Dangun.[10] Wanggeom-seong, which was in the location of Pyongyang, became the capital of Gojoseon from 194 to 108 BC. It fell in the Han conquest of Gojoseon in 108 BC. Emperor Wu of Han ordered four commanderies be set up, with Lelang Commandery in the center and its capital established as "Joseon" (朝鮮縣, 조선현) at the location of Pyongyang. Several archaeological findings from the later, Eastern Han (20–220 AD) period in the Pyongyang area seems to suggest that Han forces later launched brief incursions around these parts.

The area around the city was called Nanglang during the early Three Kingdoms period. As the capital of Nanglang (낙랑국; 樂浪國),[c] Pyongyang remained an important commercial and cultural outpost after the Lelang Commandery was destroyed by an expanding Goguryeo in 313.

Goguryeo moved its capital there in 427. According to Christopher Beckwith, Pyongyang is the Sino-Korean reading of the name they gave it in their language: Piarna, or "level land".[37]

In 668, Pyongyang became the capital of the Protectorate General to Pacify the East established by the Tang dynasty of China. However, by 676, it was taken by Silla, but left on the border between Silla and Balhae. Pyongyang was left abandoned during the Later Silla period, until it was recovered by Wang Geon and decreed as the Western Capital of Goryeo.

During the Imjin War, Pyongyang was captured by the Japanese and held the city wall until they were defeated in the Siege of Pyongyang.[10] Later in the 17th century, it became temporarily occupied during the Qing invasion of Joseon until peace arrangements were made between Korea and Qing China. While the invasions made Koreans suspicious of foreigners, the influence of Christianity began to grow after the country opened itself up to foreigners in the 16th century. Pyongyang became the base of Christian expansion in Korea. By 1880 it had more than 100 churches and more Protestant missionaries than any other Asian city,[10] and was called "the Jerusalem of the East".[38]

In 1890, the city had 40,000 inhabitants.[39] It was the site of the Battle of Pyongyang during the First Sino-Japanese War, which led to the destruction and depopulation of much of the city.[40] It was the provincial capital of South Pyeongan Province beginning in 1896. During the Japanese colonial rule, Japan tried to develop the city as an industrial center, but faced the March First Movement in 1919 and severe anti-Japanese socialist movement in 1920s due to economic exploitation.[40][41][42][43] It was called Heijō (with the same Chinese characters 平壤 but read as へいじょう) in Japanese.

In July 1931, the city experienced anti-Chinese riots as a result of the Wanpaoshan Incident and the sensationalized media reports about it which appeared in Imperial Japanese and Korean newspapers.[44] By 1938, Pyongyang had a population of 235,000.[39]

After 1945

On 25 August 1945, the Soviet 25th Army entered Pyongyang and it became the temporary capital of the Provisional People's Committee for North Korea. A People's Committee was already established there, led by veteran Christian nationalist Cho Man-sik.[45] Pyongyang became the de facto capital of North Korea upon its establishment in 1948. At the time, the Pyongyang government aimed to recapture Korea's official capital, Seoul. Pyongyang was again severely damaged in the Korean War, during which it was briefly occupied by South Korean forces from 19 October to 6 December 1950. The city saw many refugees evacuate when advancing Chinese forces pushed southward towards Pyongyang. UN forces oversaw the evacuation of refugees as they retreated from Pyongyang in December 1950.[46] In 1952, it was the target of the largest aerial raid of the entire war, involving 1,400 UN aircraft.

Already during the war, plans were made to reconstruct the city. On 27 July 1953 – the day the armistice between North Korea and South Korea was signed – The Pyongyang Review wrote: "While streets were in flames, an exhibition showing the general plan of restoration of Pyongyang was held at the Moranbong Underground Theater", the air raid shelter of the government under Moranbong. "On the way of victory... fireworks which streamed high into the night sky of the capital in a gun salute briefly illuminated the construction plan of the city which would rise soon with a new look".[47] After the war, the city was quickly rebuilt with assistance from the Soviet Union, and many buildings were built in the style of Stalinist architecture. The plans for the modern city of Pyongyang were first displayed for public viewing in a theatre building. Kim Jung-hee, one of the founding members of the Korean Architects Alliance, who had studied architecture in prewar Japan, was appointed by Kim Il Sung to design the city's master plan. Moscow Architectural Institute designed the "Pyongyang City Reconstruction and Construction Comprehensive Plan" in 1951, and it was officially adopted in 1953. The transformation into a modern, propaganda-designed city featuring Stalin-style architecture with a Korean-style arrangement (and other modernist architecture that was said to have been greatly influenced by Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer) began.[48] The 1972 Constitution officially declared Pyongyang the capital.[49]

The funeral of Kim Il Sung was held in Pyongyang in 1994. Then on 19 July, it concluded with a cortege procession when his corpse moved through the streets with a hearse as people cried out in hysteria while watching the funeral.[50]

In 2001, North Korean authorities began a long-term modernisation programme. The Ministry of Capital City Construction Development was included in the Cabinet in that year. In 2006, Kim Jong Il's brother-in-law Jang Song Thaek took charge of the ministry.

Throughout the rule of Kim Jong Un a number of residential projects were constructed. In 2012, Changjon Street,[51] a residential project with 2,784 units, was inaugurated in the heart of Pyongyang. 2013 and 2014 residential projects dedicated to scientists were completed in Unha Scientists Street and Wisong Scientists Street with more than 1,000 units each while in 2015 work took place on a residential project in Mirae Scientists Street with 2,584 units. In 2017, in dedication to the 105th birthday of the founder and first leader, Kim Il Sung, 4,804 units were built in the new Ryomyong Street complex. The second decade of the 2000s saw the construction of residential projects in Songhwa Street near the Taedonggang Brewing Company in Sadong District (2022), in Taephyong area in Mangyongdae district, and in the Pothong Riverside Terraced Residential District located at the city center next to the Pothong River on land previously used by the headquarters of the International Taekwon-Do Federation.[52] Kim Jong Un ordered that the residential district be renamed "Kyongru-dong" meaning "beautiful bead terrace".[53] From the 50s to the 70s the area was the location of the residence of Kim Il Sung and was known as "Mansion No. 5".[54] Other recent public building projects include the Mansudae People's Theatre opened in 2012, the Munsu Water Park opened in 2013, and the renovated and expanded Sunan International Airport and Pyongyang Sci-Tech Complex, both completed in 2015,[55] the Samjiyon Orchestra Theater,[56] which was fitted out of the domed Korean People's Army Circus built in 1964, and the Pyongyang General Hospital, of which construction started in 2020. Additional re-development projects occurred in the area around the Arch of Triumph where the Pyongyang People's Hospital no. 1 was demolished. Apartment blocks in the area of Inhŭng-dong, in Moranbong-guyok district and in the area of Sinwon-dong in Pothonggang district were demolished[57] in 2018–2019 for the construction of new apartment buildings.[58] Also in 2018 the Youth Park Open-Air Theatre in Sungri Street, used to host political rallies, was rebuilt.[59] In 2021–2022 a major housing project was executed along Songhwa Street in southeast part of the city[60] Hwasong Street in Hwasong District in northern Pyongyang with high-rises.[61] In 2023 phase two of construction of housing in Hwasong district was launched, on the former territory of the Pyongyang Vegetable Science Institute. In addition, a complex of greenhouse farm and housing was initiated on the former territory of Kangdong Airfield which was demolished in 2019.[62]

In April 2024 the second stage of construction in the Hwasong area was completed in Rimhung Street with 10,000 apartments was marked with an extravagant ceremony.[63]

Pyongyang, alongside Seoul, launched a bid to host the 2032 Summer Olympics, but failed to make the joint city candidate list.

Geography

Pyongyang is in the west-central part of North Korea; the city lies on a flat plain about 50 kilometres (31 mi) east of the Korea Bay, an arm of the Yellow Sea. The Taedong River flows southwestward through the city toward the Korea Bay. The Pyongyang plain, where the city is situated, is one of the two large plains on the Western coast of the Korean peninsula, the other being the Chaeryong plain. Both have an area of approximately 500 square kilometers.[64]

Climate

Pyongyang has a hot-summer continental monsoon climate (Köppen: Dwa), featuring warm to hot, humid summers and cold, dry winters.[65][66] Cold, dry winds can blow from Siberia in winter, making conditions very cold; the low temperature is usually below freezing between November and early March, although the average daytime high is at least a few degrees above freezing in every month except January. The winter is generally much drier than summer, with snow falling for 37 days on average.

The transition from the cold, dry winter to the warm, wet summer occurs rather quickly between April and early May, and there is a similarly abrupt return to winter conditions in late October and November. Summers are generally hot and humid, with the East Asian monsoon taking place from June until September; these are also the hottest months, with average temperatures of 21 to 25 °C (70 to 77 °F), and daytime highs often above 30 °C (86 °F). Although largely transitional seasons, spring and autumn experience more pleasant weather, with average high temperatures ranging from 20 to 26 °C (68 to 79 °F) in May and 22 to 27 °C (72 to 81 °F) in September,[67][68] coupled with relatively clear, sunny skies.[69][70]

| Climate data for Pyongyang (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1961–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.0 (53.6) |

17.3 (63.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

29.1 (84.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.8 (96.4) |

36.9 (98.4) |

37.9 (100.2) |

33.5 (92.3) |

30.0 (86.0) |

26.0 (78.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

37.9 (100.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −0.4 (31.3) |

3.1 (37.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

27.5 (81.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

29.6 (85.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

9.7 (49.5) |

1.4 (34.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −5.4 (22.3) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

4.0 (39.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

17.4 (63.3) |

21.9 (71.4) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

4.8 (40.6) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −9.8 (14.4) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

17.4 (63.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.5 (70.7) |

15.6 (60.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.5 (−15.7) |

−23.4 (−10.1) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

11.1 (52.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−14.0 (6.8) |

−22.8 (−9.0) |

−26.5 (−15.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 9.6 (0.38) |

14.5 (0.57) |

23.9 (0.94) |

44.8 (1.76) |

74.7 (2.94) |

90.2 (3.55) |

274.7 (10.81) |

209.6 (8.25) |

90.8 (3.57) |

47.2 (1.86) |

38.4 (1.51) |

18.0 (0.71) |

936.4 (36.87) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 3.9 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 7.1 | 7.9 | 12.5 | 10.1 | 6.3 | 5.8 | 7.1 | 5.7 | 80.1 |

| Average snowy days | 5.4 | 4.0 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 5.5 | 19.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69.1 | 65.0 | 62.5 | 60.4 | 65.3 | 72.2 | 81.1 | 80.6 | 75.3 | 72.0 | 72.2 | 70.6 | 70.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 184 | 197 | 231 | 237 | 263 | 229 | 181 | 204 | 222 | 214 | 165 | 165 | 2,492 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source 1: Korea Meteorological Administration[71] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Pogodaiklimat.ru (extremes),[72] Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun, 1961–1990)[73] and Weather Atlas[74] | |||||||||||||

Politics

Major government and other public offices are located in Pyongyang, which is constitutionally designated as the country's capital.[75] The seat of the Workers' Party Central Committee and the Pyongyang People's Committee (Korean: 平壌市人民委員会) are located in Haebangsan-dong, Chung-guyok. The Cabinet of North Korea is located in Jongro-dong, Chung-guyok.

Pyongyang is also the seat of all major North Korean security institutions. The largest of them, the Ministry of Social Security, has 130,000 employees working in 12 bureaus. These oversee activities including: police services, security of party officials, classified documents, census, civil registrations, large-scale public construction, traffic control, fire safety, civil defence, public health and customs.[76] Another significant structure based in the city is the Ministry of State Security, whose 30,000 personnel manage intelligence, political prison systems, military industrial security and entry and exit management.[77]

The politics and management of the city is dominated by the Workers' Party of Korea, as they are in the national level. The city is managed by the Pyongyang Party Committee of the Workers' Party of Korea and its chairman is the de facto mayor. The supreme standing state organ is the Pyongyang People's Committee, responsible for everyday events in support of the city. This includes following local Party guidance as channeled through the Pyongyang Party Committee, the distribution of resources prioritised to Pyongyang, and providing support to KWP and internal security agency personnel and families.

Administrative status and divisions

P'yŏngyang is divided into 19 wards (ku- or guyŏk) (the city proper), 2 counties (kun or gun), and 1 neighborhood (dong).[78]

- Chung-guyok (중구역; 中區域)

- Pyongchon-guyok (평천구역; 平川區域)

- Potonggang-guyok (보통강구역; 普通江區域)

- Moranbong-guyok (모란봉구역; 牡丹峰區域)

- Sŏsŏng-guyŏk (서성구역; 西城區域)

- Songyo-guyok (선교구역; 船橋區域)

- Tongdaewŏn-guyŏk (동대원구역; 東大院區域)

- Taedonggang-guyŏk (대동강구역; 大同江區域)

- Sadong-guyŏk (사동구역; 寺洞區域)

- Taesong-guyok (대성구역; 大城區域)

- Mangyongdae-guyok (만경대구역; 萬景台區域)

- Hyongjesan-guyok (형제산구역; 兄弟山區域)

- Hwasong-guyok (화성구역; 和盛區域)[79]

- Ryongsong-guyok (룡성구역; 龍城區域)

- Samsok-guyok (삼석구역; 三石區域)

- Ryokpo-guyok (력포구역; 力浦區域)

- Rakrang-guyok (락랑구역; 樂浪區域)

- Sunan-guyŏk (순안구역; 順安區域)

- Unjong-guyok (은정구역; 恩情區域)

- Kangdong County (강동군; 江東郡)

- Kangnam County (강남군; 江南郡)

- Panghyŏn-dong (방현동; 方峴洞)

Foreign media reports in 2010 stated that Kangnam-gun, Chunghwa-gun, Sangwŏn-gun, and Sŭngho-guyŏk had been transferred to the administration of neighboring North Hwanghae Province.[80] However, Kangnam-gun was returned to Pyongyang in 2011.[81]

Panghyŏn-dong, a missile base, was administrated by Kusong, North Pyongan Province. It had been transferred to the administration of P'yŏngyang on February 10, 2018.[82]

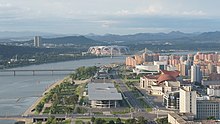

Cityscape

After being destroyed during the Korean War, Pyongyang was entirely rebuilt according to Kim Il Sung's vision, which was to create a capital that would boost morale in the post-war years.[83] The result was a city with wide, tree-lined boulevards and public buildings with terraced landscaping, mosaics and decorated ceilings.[84] Its Soviet-style architecture makes it reminiscent of a Siberian city during winter snowfall, although edifices of traditional Korean design somewhat soften this perception. In summer, it is notable for its rivers, willow trees, flowers and parkland.[84]

Since the end of the Korean War the city was planned strictly according to Socialist principles.[85] According to the 1953 masterplan designed Kim Jung-hee the city was planned to reach one-million residents stretching from the Taedong River to the Pothong River. The city center was planned as the main administrative district with main landscape structures constructed in between districts and are used as buffer zones so that they cannot expand freely.[85] The city center was planned with wide avenues and streets and monumental structures and forms the central administrative district where many government and public buildings are located including the Forbidden City as well as various monuments and memorials, which together form an important axis of symbolic places which promotes the Ideology of the Workers' Party of Korea and North Korean cult of personality around Kim family with the epicentre and Kilometre zero of the central district located at Kim Il Sung Square.[86]

The 1953 masterplan set the basic layout from which the city's development was derived in the next decades with a unit district system which mixes residential and industrial zoning. Those districts are spread around the central administrative district and together with it they form the key axis of directionality for the city expansion. While in the 50s the major emphasis was placed on the reconstruction of Pyongyang from its ruins as carefully a socialist city in strict line with the masterplan, the 60s and 70s saw new wave of development which included expansion of the central boulevards, construction of high-density apartment buildings along the central boulevards, grandiose civic and cultural buildings and monumental statues and squares. This tendency included also the inclusion of traditional Korean architecture for some buildings. While the development generally followed the 1953 master plan, it diverted from it in some aspects, such as the construction of high-rises along the central avenues, a step conflicted with the 1953 plan which called for more even distribution of the residential construction throughout the city in several multi-cores.[85] The 90s saw a relative slowdown in the development of the urban structure due to the deep economic crisis and famine which swept through North Korea and led to the diversion of resources to the army. The 2010s and 2020s saw renewed efforts in urbanization and increasing density with the reconstruction of streets and avenues located further from the center and transformation of former rural parts of the city into high density residential districts.

The streets are laid out in a north–south, east–west grid, giving the city an orderly appearance.[84] North Korean designers applied the Swedish experience of self-sufficient urban neighbourhoods throughout the entire country, and Pyongyang is no exception. Its inhabitants are mostly divided into administrative units of 5,000 to 6,000 people (dong). These units all have similar sets of amenities including a food store, a barber shop, a tailor, a public bathhouse, a post office, a clinic, a library and others. Many residents occupy high-rise apartment buildings.[87] One of Kim Il Sung's priorities while designing Pyongyang was to limit the population. Authorities maintain a restrictive regime of movement into the city, making it atypical of East Asia as it is silent, uncrowded and spacious.[88]

Structures in Pyongyang are divided into three major architectural categories: monuments, buildings with traditional Korean motifs and high-rises.[89] Some of North Korea's most recognisable landmarks are monuments, like the Juche Tower, the Arch of Triumph and the Mansu Hill Grand Monument. The first of them is a 170-meter (560 ft) granite spire symbolizing the Juche ideology. It was completed in 1982 and contains 25,550 granite blocks, one for each day of Kim Il Sung's life up to that point.[89] The most prominent building on Pyongyang's skyline is Ryugyong Hotel,[89] the seventh highest building in the world terms of floor count, the tallest unoccupied building in the world,[90] and one of the tallest hotels in the world. It has yet to open.[91][92]

Pyongyang has a rapidly evolving skyline, dominated by high-rise apartment buildings. A construction boom began with the Changjon Street Apartment Complex, which was completed in 2012.[93] Construction of the complex began after late leader Kim Jong Il described Changjon Street as "pitiful".[94] Other housing complexes are being upgraded as well, but most are still poorly insulated, and lacking elevators and central heating.[95] An urban renewal program continued under Kim Jong Un's leadership, with the old apartments of the 1970s and '80s replaced by taller high rise buildings and leisure parks like the Kaesong Youth Park, as well as renovations of older buildings.[96] In 2018, the city was described as unrecognizable compared to five years before.[97]

Landmarks

Notable landmarks in the city include:

- The Ryugyong Hotel

- The Kumsusan Palace of the Sun

- The Arch of Triumph (heavily inspired by, but larger than, Paris's Arc de Triomphe)

- The birthplace of Kim Il Sung at Mangyongdae Hill at the city outskirts

- Juche Tower

- Two large stadiums:

- The Mansu Hill complex, including the Korean Revolution Museum

- Kim Il Sung Square

- Yanggakdo International Hotel

Pyongyang TV Tower is a minor landmark. Other visitor attractions include the Korea Central Zoo. The Reunification Highway stretches from Pyongyang to the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).

- Monuments and sights of Pyongyang

- Juche Tower Monument to the philosophy of Juche (self-reliance)

Culture

Cuisine

Pyongyang served as the provincial capital of South Pyongan Province until 1946,[98] and Pyongyang cuisine shares the general culinary tradition of the Pyongan province. The most famous local food is Pyongyang raengmyŏn, or also called mul raengmyŏn or just simply raengmyŏn. Raengmyŏn literally means "cold noodles", while the affix mul refers to water because the dish is served in a cold broth. Raengmyŏn consists of thin and chewy buckwheat noodles in a cold meat-broth with dongchimi (watery kimchi) and topped with a slice of sweet Korean pear.

Pyongyang raengmyŏn was originally eaten in homes built with ondol (traditional underfloor heating) during the cold winter, so it is also called "Pyongyang deoldeori" (shivering in Pyongyang). Pyongyang locals sometimes enjoyed it as a haejangguk, which is any type of food eaten as a hangover cure, usually a warm soup.[99]

Another representative Pyongyang dish, Taedonggang sungeoguk, translates as "flathead grey mullet soup from the Taedong River". The soup features flathead grey mullet (abundant in the Taedong River) along with black peppercorns and salt.[100] Traditionally, it has been served to guests visiting Pyongyang. Therefore, there is a common saying, "How good was the trout soup?", which is used to greet people returning from Pyongyang. Another local specialty, Pyongyang onban (literally "warm rice of Pyongyang") comprises freshly cooked rice topped with sliced mushrooms, chicken, and a couple of bindaetteok (pancakes made from ground mung beans and vegetables).[99]

Social life

In 2018, there were many high-quality restaurants in Pyongyang with Korean and international food, and imported alcoholic beverages.[97] Famous restaurants include Okryu-gwan and Ch'ongryugwan.[101] Some street foods exist in Pyongyang, where vendors operate food stalls.[102] Foreign foods like hamburgers, fries, pizza, and coffee are easily found.[97] There is an active nightlife with late-night restaurants and karaoke.[97]

The city has water parks, amusement parks, skating rinks, health clubs, a shooting range, and a dolphinarium.[96]

Sports

Pyongyang has a number of sports clubs, including the April 25 Sports Club and the Pyongyang City Sports Club.[103]

Economy

Pyongyang is North Korea's industrial center.[10] Thanks to the abundance of natural resources like coal, iron and limestone, as well as good land and water transport systems, it was the first industrial city to emerge in North Korea after the Korean War. Light and heavy industries are both present and have developed in parallel. Heavy manufactures include cement, industrial ceramics,[40] munitions and weapons, but mechanical engineering remains the core industry. Light industries in Pyongyang and its vicinity include textiles, footwear and food, among others.[40] Special emphasis is put on the production and supply of fresh produce and subsidiary crops in farms on the city's outskirts. Other crops include rice, sweetcorn and soybeans. Pyongyang aims to achieve self-sufficiency in meat production. High-density facilities raise pigs, chicken and other livestock.[10]

Until the late 2010s Pyongyang still experienced frequent shortages of electricity.[104] To solve this problem, two power stations – Huichon Power Stations 1 and 2 – were built in Chagang Province and supply the city through direct transmission lines. A second phase of the power expansion project was launched in January 2013, consisting of a series of small dams along the Chongchon River. The first two power stations have a maximum generating capacity of 300 megawatts (MW), while the 10 dams to be built under second phase are expected to generate about 120 MW.[104] In addition, the city has several existing or planned thermal power stations. These include Pyongyang TPS with a capacity of 500 MW, East Pyongyang TPS with a capacity of 50 MW, and Kangdong TPS which is under construction.[105]

Retail

Pyongyang is home to several large department stores including the Pothonggang Department Store, Pyongyang Department Store No. 1, Pyongyang Department Store No. 2, Kwangbok Department Store, Ragwon Department Store, Pyongyang Station Department Store, and the Pyongyang Children's Department Store.[106]

The city also has Hwanggumbol Shop, a chain of state-owned convenience stores supplying goods at prices cheaper than those in the jangmadang markets. Hwanggumbol Shops are specifically designed to control North Korea's expanding markets by attracting consumers and guaranteeing the circulation of money in government-operated stores.[107]

Transportation

Pyongyang is the main transport hub of the country: it has a network of roads, railways and air routes which link it to both foreign and domestic destinations. It is the starting point of inter-regional highways reaching Nampo, Wonsan and Kaesong.[10] Pyongyang railway station serves the main railway lines, including the Pyongui Line and the Pyongbu Line. Regular international rail services to Beijing, the Chinese border city of Dandong and Moscow are also available.

A rail journey to Beijing takes about 25 hours and 25 minutes (K27 from Beijing/K28 from Pyongyang, on Mondays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays); a journey to Dandong takes about 6 hours (daily); a journey to Moscow takes six days. The city also connects to the Eurasian Land Bridge via the Trans-Siberian Railway. A high-speed rail link to Wonsan is planned.[108]

The Metro, tram and trolleybus systems are used mainly by commuters as a primary means of urban transportation.[10] Cycle lanes were introduced on main thoroughfares in July 2015.[109] There are relatively few cars in the city. Cars are a symbol of status in the country due to their scarcity as a result of restrictions on import because of international sanctions and domestic regulations.[110] Some roads are also reported to be in poor condition.[111] However, by 2018, Pyongyang had begun to experience traffic jams.[97]

State-owned Air Koryo has scheduled international flights from Pyongyang Sunan International Airport to Beijing (PEK), Shenyang (SHE), Vladivostok (VVO), Shanghai (PVG) and Dandong.[112] The only domestic destinations are Hamhung, Wonsan, Chongjin, Hyesan and Samjiyon. Since 31 March 2008, Air China launched a regular service between Beijing and Pyongyang,[113] although Air China's flights are often canceled due to lack of passengers.[114]

Education and science

Kim Il Sung University, North Korea's oldest university, was established in 1946.[10] It has 21 faculties, 4 research institutes, and 10 other university units.[115][116][117] These include the primary medical education and health personnel training unit, the medical college; a physics faculty which covers a range of studies including theoretical physics, optical science, geophysics and astrophysics;[118] an atomic energy institute and the largest law firm in the country (Ryongnamsan Law Office).[119] Kim Il Sung University also has its own publishing house, sports club (Ryongnamsan Sports Club),[120] revolutionary museum, nature museum, libraries, a gym, indoor swimming pool and educator apartment houses. Its four main buildings were completed in 1965 (Building 1), 1972 (Building 2), and 2017 (Buildings 3 and 4).[121][122][123]

Other higher education establishments include Kim Chaek University of Technology, Pyongyang University of Music and Dance and Pyongyang University of Foreign Studies. Pyongyang University of Science and Technology (PUST) is the country's first private university where most of the lecturers are American and courses are carried out in English.[124][125] A science and technology hall is under construction on Ssuk Islet. Its stated purpose is to contribute to the "informatization of educational resources" by centralizing teaching materials, compulsory literature and experimental data for state-level use in a digital format.[126]

Sosong-guyok hosts a 20 MeV cyclotron called MGC-20. The initial project was approved by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in 1983 and funded by the IAEA, the United States and the North Korean government. The cyclotron was ordered from the Soviet Union in 1985 and constructed between 1987 and 1990. It is used for student training, production of medical isotopes for nuclear medicine as well as studies in biology, chemistry and physics.[127]

Health care

Medical centers include the Red Cross Hospital, the First People's Hospital which is located near Moran Hill and was the first hospital to be built in North Korea after the liberation of Korea in 1945,[128] the Second People's Hospital, Ponghwa Recuperative Center (also known as Bonghwa Clinic or Presidential Clinic) located in Sokam-dong, Potonggang-guyok, 1.5 km (1 mi) northwest of Kim Il Sung Square,[129] Pyongyang Medical School Hospital, Namsan Treatment Center which is adjacent[130] Pyongyang's Maternity Hospital, Taesongsan General Hospital,[131] Kim Man-yoo Hospital, Staff Treatment Center and Okryu Children's Hospital. A new hospital named Pyongyang General Hospital began construction in Pyongyang in 2020.[132]

Twin towns – sister cities

Pyongyang is twinned with:[133]

Baghdad, Iraq

Baghdad, Iraq Chiang Mai, Thailand

Chiang Mai, Thailand Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Dubai, United Arab Emirates Jakarta, Indonesia

Jakarta, Indonesia Kathmandu, Nepal

Kathmandu, Nepal Moscow, Russia

Moscow, Russia Tianjin, China

Tianjin, China Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia[134]

Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia[134]

See also

Notes

- ^ English: /pjɒŋˈjæŋ, pjʌŋ-, -jɑːŋ/ ;[5][6][7] Korean: [pʰjʌŋjaŋ]

- ^ These include: Heijō-fu,[18] Heizyō,[19] Heizyō Hu,[20] Hpyeng-yang,[21] P-hjöng-jang,[22] Phyeng-yang,[23] Phyong-yang,[24] Pienyang,[25] P'ing-jang,[26][27] Pingrang,[26][28] Pingyang,[29] Pyengyang,[30] and Pieng-tang.[31]

- ^ Nanglang-state is different from Lelang Commandery.

References

Citations

- ^ Funabashi, Yoichi (2007). The Peninsula Question: A Chronicle of the Second Northern Korean Nuclear Crisis. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8157-3010-1.

- ^ Nick Heath-Brown (ed.). The Statesman's Yearbook 2016: The Politics, Cultures and Economies of the World. p. 720.

- ^ United Nations. "Democratic People's Republic of Korea". Data.un.org. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ^ Specialties of Korea (PDF). Foreign Languages Publishing House. 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-40588118-0.

- ^ "Pyongyang definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". Archived from the original on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ "Definition of P'YŎNGYANG". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ "「혁명의 수도」선포...금속·건재 공업이 주류". JoongAng Ilbo (in Korean). 3 July 1989. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ D P R Korea, 2008 Population Census, National Report (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Pyongyang". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Collins, Robert (2012). Marked for Life: Songbun, North Korea's Social Classification System (PDF). United States: Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. p. 69. ISBN 978-0985648008. LCCN 2012939299.

- ^ a b c ""'평양(平壤)' 지명은 '부루나'에서 유래"". SPN 서울평양뉴스 (in Korean). 30 March 2023.

- ^ a b 평양이라는 이름의 유래. Uriminzokkiri. Archived from the original on 17 November 2023.

- ^ Funabashi, Yōichi (2007). The peninsula question : a chronicle of the second Korean nuclear crisis. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-3011-8. OCLC 290569447.

- ^ "Map - Pyongyang - MAP[N]ALL.COM". www.mapnall.com. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Japan and Korea compiled and drawn in the Cartographic Section of the National Geographic Society for The National Geographic Magazine (Map). Washington: Gilbert Grosvenor. 1945. OCLC 494696670. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ "Heijō: North Korea". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "Heijō-fu: North Korea". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "Heizyō: North Korea". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "Heizyō Hu: North Korea". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "Hpyeng-yang: North Korea". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "P-hjöng-jang: North Korea". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "Phyeng-yang: North Korea". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "Phyong-yang: North Korea". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "Pienyang: North Korea". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ a b Blunden, Caroline (1998). "Gazetteer". Cultural Atlas of China (Revised ed.). Facts on File. pp. 232, 235. ISBN 0-8160-3814-7. LCCN 98-34322. OCLC 43168341.: "Names in italics represent the Wade-Giles equivalent of the preceding Pinyin transcription....Pingrang/P'ing-jang see Pyongyang"

- ^ William H. Harris; Judith S. Levey, eds. (1975). "Pyongyang". The New Columbia Encyclopedia (Fourth ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 2250. ISBN 0-231-03572-1. LCCN 74-26686. OCLC 1103123. "Chin. P'ing-jang"

- ^ Wilkinson, Endymion (2012). "Introduction". Chinese History: A New Manual (Third, revised ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-674-06715-8. LCCN 2011285309. OCLC 873859851. "The DPRK (Joseon Minjujui Inmin Konghuaguk 朝鮮民主主義人民共和國) is read in Chinese as Chaoxian minzhu zhuyi renmin gonghe guo, and its capital, Pyeonyang, is pronounced Pingrang 平壤."

- ^ "Pingyang: North Korea". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "Pyengyang: North Korea". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ EB (1878), p. 390.

- ^ Hermann Lautensach (1988). Korea: A Geography Based on the Author's Travels and Literature. Springer. p. 9. ISBN 9783642735783. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ^ Lankov, Andrei (16 March 2005). "North Korea's missionary position". Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on 18 March 2005. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

By the early 1940s Pyongyang was by far the most Protestant of all major cities of Korea, with some 25–30% of its adult population being church-going Christians. In missionary circles this earned the city the nickname "Jerusalem of the East".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Caryl, Christian (15 September 2007). "Prayer in Pyongyang". The Daily Beast. The Newsweek/Daily Beast Co. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

It's hard to say how many covert Christians the North has; estimates range from the low tens of thousands to 100,000. Christianity came to the peninsula in the late 19th century. Pyongyang, in fact, was once known as the 'Jerusalem of the East.'

- ^ "Pyongyang was to become 'Kim Il Sung City'; The followers of Kim Jong Il suggested the idea". Daily NK. 21 February 2005. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage. 2001. Geumtan-ri. Hanguk Gogohak Sajeon [Dictionary of Korean Archaeology], pp. 148–149. NRICH, Seoul. ISBN 89-5508-025-5

- ^ Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.

- ^ "Pyongyang, one-time Jerusalem of East". The Korea Times. 4 March 2021. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ a b Lahmeyer, Jan. "North Korea – Urban Population". Populstat. University of Utrecht. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d "P'yŏngyang | national capital, North Korea | Britannica". 29 May 2023. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "March 1st movement Pyongyang". 5 March 2019. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "朝鮮物産奨励運動". Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ 물산장려운동. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Memorandum (Institute of Pacific Relations, American Council), Vol. 2, No. 5 (16 Mar 1933), pp. 1–3

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 54–57. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ^ "Pyongyang taken as UN retreats, 1950". BBC Archive. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Schinz, Alfred; Eckart, Dege (1990). "Pyongyang-Ancient and Modern – the Capital of North Korea". GeoJournal. 22 (1): 25. doi:10.1007/BF02428536. S2CID 153574542.

- ^ 金聖甫、李信澈「写真と絵で見る北朝鮮現代史」監修: 李泳采、韓興鉄訳、コモンズ、東京・新宿(原著2010年12月1日).ISBN 978-4861870750.2018年4月30日閲覧.

- ^ "Korea (Democratic People's Republic of) 1972 (rev. 1998) Constitution - Constitute". www.constituteproject.org. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ^ "Crying by numbers at Kim's state funeral". The Independent. 19 July 1994. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ^ [통일문화가꿔가기 38] 평양 창전거리 건설 비하인드 소설《강자》. 자주시보. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ Williams, Martyn (15 April 2021). "Pyongyang Development Projects off to a Strong Start". 38 North. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Kim Jong Un visits construction site for new luxury apartments in Pyongyang | NK News". NK News. 21 August 2021. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "North Korean leader Kim Jong Un builds luxury villas over grandfather's old home". Radio Free Asia. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Féron, Henri (18 July 2017). "Pyongyang's Construction Boom: Is North Korea Beating Sanctions?". 38 North. Archived from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Cheong-mo, Yoo (11 October 2018). "N. Korean leader visits newly renovated orchestra theater in Pyongyang". Yonhap News Agency. Archived from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Zwirko, Colin (9 January 2019). "Major demolition underway in central Pyongyang's Moranbong district: imagery | NK News". NK News. Archived from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Zwirko, Colin (14 June 2022). "Major construction springs up in shadow of infamous Pyongyang hotel: Imagery". NK PRO. Archived from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Newstream". Archived from the original on 7 April 2023.

- ^ Colin Zwirko (26 February 2024). "North Korea kicks off fourth 10,000-home project in capital in four years". NK News. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ Colin Zwirko (23 February 2023). "North Korea adds skyscraper, simplifies designs for major new housing project". NK News. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Colin Zwirko (16 February 2023). "Kim Jong Un opens construction on major housing and farm projects in capital". NK News. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Colin Zwirko (17 April 2024). "Kim Jong Un debuts new song praising himself at grand opening of housing project". NK News. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 63.

- ^ Muller, M. J. (6 December 2012). Selected climatic data for a global set of standard stations for vegetation science. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-009-8040-2. Archived from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ "Pyongyang, North Korea Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ "Average Weather in May in Pyongyang, North Korea - Weather Spark". weatherspark.com. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Average Weather in September in Pyongyang, North Korea - Weather Spark". weatherspark.com. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Average Weather in Pyongyang, North Korea, Year Round - Weather Spark". weatherspark.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Average Weather in Pyongyang, North Korea, Year Round - Weather Spark". weatherspark.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "30 years report of Meteorological Observations in North Korea (1991 ~ 2020)" (PDF) (in Korean). Korea Meteorological Administration. pp. 199–367. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ "Climate Pyongyang". Pogoda.ru.net. Archived from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "PYONGYANG SUN 1961–1990". DWD. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Pyongyang, North Korea - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Yu Media Group. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 196.

- ^ Country Study 2009, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 277.

- ^ "Haengjeong Guyeok Hyeonhwang" 행정구역현황. NK Chosun. Archived from the original on 9 January 2006. Retrieved 10 January 2006. Also Administrative divisions of North Korea Archived 18 October 2004 at the Wayback Machine (used as reference for hanja)

- ^ 조선중앙통신 | 기사 | 화성지구의 행정구역명칭을 정하였다. Korean Central News Agency. Archived from the original on 15 April 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ "Pyongyang now more than one-third smaller; food shortage issues suspected". Asahi Shimbun. 17 July 2010. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ^ "Kangnam moved into Pyongyang". North Korean Economy Watch. 29 February 2012. Archived from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ 안준용. "北, 평양서 150km 떨어진 곳을 평양市에 편입 왜?". The Chosun Ilbo. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 91,93–94.

- ^ a b c Country Study 2009, p. 91.

- ^ a b c Dongwoo Yim (24 August 2017). "A brief urban history of Pyongyang, North Korea—and how it might develop under capitalism". The Architect's Newspaper. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Talmadge, Eric (20 November 2017). "Lonely highways: On the road in Kim Jong Un's North Korea". Associated Press. AP. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 97.

- ^ Country Study 2009, p. 91-92.

- ^ a b c "Architecture and City Planning". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Glenday, Craig (2013). Guinness World Records 2014. Guinness World Records Limited. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

- ^ "Will 'Hotel of Doom' ever be finished?". BBC News. BBC. 15 October 2009. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Yoon, Sangwon (1 November 2012). "Kempinski to Operate World's Tallest Hotel in North Korea". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 14 January 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Gray, Nolan (16 October 2018). "The Improbable High-Rises of Pyongyang, North Korea". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ Lee, Seok Young (25 August 2011). ""Pitiful" Changjeon Street the Top Priority". Daily NK. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ "Pyongyang glitters but most of NKorea still dark". Yahoo News. 29 April 2013. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ a b Makinen, Julie (20 May 2016). "North Korea is building something other than nukes: architecture with some zing". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Salmon, Andrew (4 December 2018). "Going native in the Hermit Kingdom". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ 평양시 平壤市 [Pyongyang] (in Korean). Nate/Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011.

- ^ a b 닮은 듯 색다른 매력을 간직한 북한의 음식 문화 (in Korean). Korea Knowledge Portal. 19 June 2009. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011.

- ^ Ju, Wan-jung (주완중) (12 June 2000). '오마니의 맛' 관심 [Attention to "Mother's taste"]. The Chosun Ilbo (in Korean).

- ^ Lankov, Andrei (2007). North of the DMZ: Essays on daily life in North Korea. Jefferson: McFarland. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-7864-2839-7.

- ^ Pearson, James; Yeom, Seung-Woo. "Fake meat and free markets ease North Koreans' hunger". Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ "The Sights and Sounds of Domestic Football in North Korea". Footy Fair. August 2015. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Ten Power Plants on Chongchon River under Construction to Increase Power Supply to Pyongyang". Institute for Far Eastern Studies. 19 December 2014. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Pyongyang's Perpetual Power Problems". 38 North. 25 November 2014. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Pyongyang Metro maps". pyongyang-metro.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Effort to Prevent Outflow of Capital into Markets". Institute for Far Eastern Studies. 20 March 2015. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Outline for Development of Wonsan-Kumgangsan Tourist Region Revealed". Institute for Far Eastern Studies. 26 March 2015. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "North Korea installs bike lanes in Pyongyang". Telegraph. Reuters. 14 July 2015. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ Martin, Bradley K. (9 July 2007). "In Kim's North Korea, Cars Are Scarce Symbols of Power, Wealth". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ Fisher, Max (16 April 2012). "North Korean Press Bus Takes Wrong Turn, Opening Another Crack in the Hermit Kingdom". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ "Air Koryo opens new office selling tickets for third country travel". NK News. 7 December 2016. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ 国航开通北京至平壤航线(组图)- 手机新浪网. sina.cn. 15 April 2017. Archived from the original on 15 April 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ 国航17日起暂停平壤航线 _手机新浪网. sina.cn. 14 April 2017. Archived from the original on 15 April 2017.

- ^ "Faculties - KIM IL SUNG UNIVERSITY". 30 June 2022. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Research Institutes - KIM IL SUNG UNIVERSITY". 30 June 2022. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Units - KIM IL SUNG UNIVERSITY". 30 June 2022. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Colleges and Faculties". Kim Il Sung University. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Ryongnamsan Law Office - KIM IL SUNG UNIVERSITY". 30 June 2022. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Research Institutes and Units". Kim Il Sung University. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Main Buildings". Kim Il Sung University. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Building No. 3 - KIM IL SUNG UNIVERSITY". 1 July 2022. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Building No. 4 - KIM IL SUNG UNIVERSITY". 1 July 2022. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Inside North Korea's Western-funded university". BBC News. 3 February 2014. Archived from the original on 5 June 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "In North Korea, a Western-backed university". The Washington Post. 8 October 2011. Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Science and Technology Hall to be Built in Pyongyang's Ssuk Islet". Institute for Far Eastern Studies. 23 January 2015. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "MGC-20 Cyclotron". NTI.org. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Pyongyang City People's Hospital No. 1". KCNA. 22 May 2002. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014.

- ^ "Ponghwa Clinic Expanded During 2009-2010, NK Leadership Watch". Nkleadershipwatch.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Where Did Kim Jong Il Receive His Surgery?". North Korean Economy Watch. 25 June 2007. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ "I Had A Scary Encounter With North Korea's Crumbling Healthcare System". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ Williams, Martyn (3 April 2020). "Construction Progressing Rapidly at the Pyongyang General Hospital". 38 North. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ Corfield, Justin (2013). "Sister Cities". Historical Dictionary of Pyongyang. London: Anthem Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-85728-234-7. Archived from the original on 18 February 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ "Хотын дарга С.Батболд Токио хотын засаг дарга Юрико Койкэтэй уулзлаа" (in Mongolian). Mongolian Government. 20 April 2017. Archived from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

Bibliography

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. VI (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1878. pp. 390–394..

- "North Korea – A Country Study" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2010.

Further reading

- Dormels, Rainer. North Korea's Cities: Industrial Facilities, Internal Structures and Typification. Seoul, Jimoondang, 2014. ISBN 978-89-6297-167-5.

- Em, Pavel P.; et al. (Spring 2021). "City Profile of Pyongyang 3.0: Inside Out". North Korean Review. 17 (1): 30–56. ISSN 1551-2789. JSTOR 27033549.

- Kim Chun-hyok (2014). Panorama of Pyongyang (PDF). Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House. ISBN 978-9946-0-1176-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 June 2020.

- Kracht, Christian, Eva Munz & Lukas Nikol. The Ministry of Truth: Kim Jong Il's North Korea. Feral House, October 2007. ISBN 978-1-93259527-7.

- Meuser, Philipp, editor. Architectural and Cultural Guide Pyongyang. Berlin, DOM, 2012. ISBN 978-3-86922-187-8.

- Springer, Chris. Pyongyang: The Hidden History of the North Korean Capital. Saranda Books, 2003. ISBN 963-00-8104-0.

- Thak, Song Il; Jang, Hyang Ok, eds. (2021). Pyongyang in Kim Jong Un's Era (PDF). Translated by Tong, Kyong Chol. DPRK Korea: Foreign Languages Publishing House. ISBN 978-9946-0-2016-7.

- Willoughby, Robert. North Korea: The Bradt Travel Guide. Globe Pequot, 2003. ISBN 1-84162-074-2.

External links

- Interactive virtual tour Aerial view of Pyongyang city

- Super High Resolution Image Panoramic view of Pyongyang city

- 22-minute video of bus ride through Pyongyang, DPRK on YouTube

- North Korea Uncovered (North Korea Google Earth), a comprehensive mapping of North Korea, including all of the locations mentioned above, on Google Earth

- Holidays in Pyongyang

- Instagram photos of Pyongyang

- City profile of Pyongyang Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine