Prince William County, Virginia

Prince William County | |

|---|---|

| County of Prince William | |

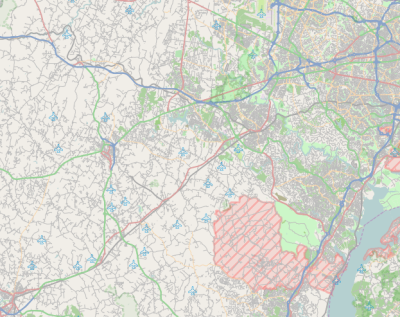

Interactive map of Prince William County | |

Location within the Commonwealth of Virginia | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1731 |

| Named for | Prince William, Duke of Cumberland |

| County seat | Manassas |

| Largest community | Dale City |

| Government | |

| • Body | Board of Supervisors |

| • Chair | Deshundra Jefferson (D) |

| • County Executive | Christopher Shorter |

| Area | |

• Total | 348 sq mi (900 km2) |

| • Land | 336 sq mi (870 km2) |

| • Water | 12 sq mi (30 km2) 3.5% |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 482,204 |

| • Density | 1,400/sq mi (500/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Area code | 703/571 |

| FIPS code | 51153 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1480161 |

| U.S. House | 7th, 10th |

| Virginia Senate | 13th, 28th, 29th, 36th, 39th |

| Virginia House | 2nd, 13th, 31st, 40th, 51st, 87th |

| Website | http://www.pwcgov.org/ |

38°42′N 77°29′W / 38.70°N 77.48°WPrince William County lies beside the Potomac River in the Commonwealth of Virginia. At the 2020 census, the population was 482,204,[1] making it Virginia's second most populous county. The county seat is the independent city of Manassas.[2] A part of Northern Virginia, Prince William County is part of the Washington metropolitan area. In 2020, it had the 24th highest income of any county in the United States.[3]

History

At the time of European colonization, the native tribes of the area that would become Prince William County were the Doeg, an Algonquian-speaking sub-group of the Powhatan tribal confederation. When John Smith and other English explorers ventured to the upper Potomac River, beginning in 1608, they recorded the name of a village that the Doeg inhabited as Pemacocack (meaning "plenty of fish" in their language). It was on the west bank of the Potomac River, about 30 miles south of present-day Alexandria.[4] Unable to deal with European diseases and firepower, the Doeg abandoned their villages in the area by 1700.[5]

Creation and divisions in colonial and early statehood era

As population increased in the area, the General Assembly of the colony of Virginia split Stafford County, Virginia in 1731, and added a section which had previously been part of King George County in order to create Prince William County.[6] The county was named for Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, the third son of King George II.[7] The area encompassed by the 1731 act creating Prince William County originally included all of what later became the counties of Arlington, Fairfax, Fauquier, and Loudoun; and the independent cities of Alexandria, Fairfax, Falls Church, Manassas, and Manassas Park. Fairfax County was split from Prince William County in 1742, and first Loudoun (in 1757) and then the incorporated town of Alexandria (in 1779, part of which later became Arlington County) would later be split from Fairfax County. Fauquier County was created from western Prince William County in 1759.

In 1790 Prince William County's population was 58% white; most of the remainder were enslaved African Americans. The county had been an area of tobacco plantations, but planters were changing to cultivate mixed crops due to soil exhaustion and changes in the market. In the first two decades after the Revolution, the number and percentage of free blacks increased in Virginia as some whites freed their slaves, based on revolutionary ideals.

Post-Reconstruction era to present

On March 19, 1892, two caucasian men, Lee Heflin and Joseph Dye, were lynched in Haymarket. They had been convicted of the murder of a girl and sentenced to death, but the mob did not want to wait for the legal system. The men were hanged from trees at the edge of woods; then the mob shot into their bodies. The Washington Post said, "mob law...is a dangerous thing to encourage. There is too much of it already throughout the country, and it spreads like a contagion so long as public sentiment tacitly approves it."[8] It was unusual that white men were lynched; in Virginia and the rest of the South, black men were overwhelmingly the victims of lynching, the violence by which whites maintained dominance.[9][10][11]

The county was rural and agricultural for decades. Into the early 20th century, the population was concentrated in two areas, one at Manassas (site of a major railroad junction), and the other near Occoquan and Woodbridge along the Potomac River, which was an important transportation route. Beginning in the late 1930s, suburban residential development began, and new housing was developed near the existing population centers, particularly in Manassas.

In 1960 the population was 50,164. Continued suburbanization and growth of the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area caused that to increase rapidly in the following decades. There was expansion of federal, military and commercial activities in Northern Virginia in the late 20th century. By 2000, this was the third-most populous local jurisdiction in Virginia. From 2000 to 2010, the population increased by 43.2%. During this period the county became minority-majority: the new majority is composed of Hispanic (of any race, largely of Central and South American ancestry), African American, and Asian.[12] In 2012 it was the seventh-wealthiest county in the country.[13] The estimated population of 2014 is more than 437,000.

In 1994 The Walt Disney Company bought extensive amounts of land in Haymarket for a proposed Disney's America theme park.[14] Local resistance to the resort, because of its perceived adverse effects on the historic Manassas Battlefield, led to its end as a viable idea.[15] William B. Snyder, a local business man convinced Disney to sell the property to him.[16] Snyder, in turn, sold off most of the land to developers, except for the 405 acres (1.64 km2) donated to the National Capital Area Council of the Boy Scouts, who used the land to create Camp Snyder for Cub Scouts.[17]

The Marine Corps Heritage Museum and the Hylton Performing Arts Center opened in the 21st century. The American Wartime Museum is also to be located in this county. During the commemoration of the Sesquicentennial of the Civil War, re-enactment of the famous First and Second Battles of Manassas was planned.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 348 square miles (900 km2), of which 336 square miles (870 km2) is land and 12 square miles (31 km2) (3.5%) is water.[18] It is bounded on the north by Loudoun and Fairfax Counties; on the west by Fauquier County; on the south by Stafford County; and on the east by the Potomac River (Charles County, Maryland lies across the river). The western half of the county is occupied by a green belt known as the rural crescent.[19]

The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the independent cities of Manassas and Manassas Park with Prince William County (within which the two cities are enclaves) for statistical purposes:

| Name | Area (km2) | Population 2000 Census |

Population 2010 Census |

Population 2020 Census |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manassas (city) | 25.59 | 35,135 | 37,821 | 42,772 |

| Manassas Park (city) | 6.55 | 10,290 | 14,273 | 17,219 |

| Prince William County | 871.27 | 280,813 | 402,002 | 482,204 |

| Totals | 903.41 | 326,238 | 454,096 | 542,195 |

Adjacent jurisdictions

- Loudoun County – north

- Fairfax County – northeast

- Charles County, Maryland – southeast

- Stafford County – south

- Fauquier County – west

- Manassas – center (enclave)

- Manassas Park – center (enclave)

National protected areas

- Featherstone National Wildlife Refuge

- Manassas National Battlefield Park

- Occoquan Bay National Wildlife Refuge

- Prince William Forest Park

Government

County elected offices

The county is divided into seven magisterial districts: Brentsville, Coles, Potomac, Gainesville, Neabsco, Occoquan, and Woodbridge. The magisterial districts each elect one supervisor to the Board of Supervisors which governs Prince William County. There is also a chairman elected by the county at-large, bringing total board membership to 8. A vice-chairman is selected by the board from among its membership. The county operates under the county form of the county executive system of government, with an elected Board of Supervisors. The board appoints a professional, nonpartisan county executive to manage operations of government agencies.

Christopher Shorter was named County Executive for Prince William County, Virginia, by the Board of County Supervisors in October 2022. Prior to serving as the County Executive in Prince William County, he served as the first City Administrator in the City of Baltimore, Assistant City Manager in Austin, Texas, and served for more than 10 years in various leadership roles for the District of Columbia government, including Director of the DC Department of Public Works.

In other elected County offices, the Prince William County Commonwealth's Attorney, Amy Ashworth, and the Prince William County Clerk of Circuit Court, Jacqueline Smith are Democrats. The Prince William County Sheriff, Glen Hill, is a Republican.

| Name | Party | First Election | District | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deshundra L. Jefferson, Chairman | Dem | 2023 | At-Large | |

| Tom Gordy | Rep | 2023 | Brentsville | |

| Yesli Vega | Rep | 2019 | Coles | |

| Robert B. Weir | Rep | 2023 | Gainesville | |

| Victor Angry | Dem | 2019 | Neabsco | |

| Kenny A. Boddye | Dem | 2019 | Occoquan | |

| Andrea O. Bailey | Dem | 2019 | Potomac | |

| Margaret Angela Franklin | Dem | 2019 | Woodbridge | |

| Position | Name | Party | First Election | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheriff | Glendell Hill | Rep | 2003 | |

| Commonwealth's Attorney | Amy Ashworth | Dem | 2019 | |

| Clerk of Circuit Court | Jacqueline Smith | Dem | 2017 | |

State elected offices

Republicans formerly held six of the eight Virginia House of Delegates seats that include parts of the county, with that delegation having consisted of Robert G. Marshall, Scott Lingamfelter, Tim Hugo, Jackson Miller, Rich Anderson, and Mark Dudenhefer. In the 2017 legislative election, which saw the Democrats cut a Republican majority in the House of Delegates from 66 to 51, Prince William County saw its number of Republican Delegates be reduced from six to one, with Tim Hugo being the sole Republican to represent the county. Marshall, Lingamfelter, Miller, and Anderson all ran for reelection and were defeated by Democratic challengers Danica Roem, Elizabeth Guzmán, Lee Carter, and Hala Ayala respectively. Dudenhefer opted to retire and instead successfully ran for a seat on the Stafford County Board of Supervisors, and he was replaced by Democrat Jennifer Carroll Foy. Democrats Luke Torian and John Bell were already representing the county in the House at the time of the 2017 elections, and with the addition of the five newcomers, Democrats held seven of the eight House seats that include parts of Prince William County. Hugo was then defeated in the 2019 election by Democrat Dan Helmer and Democrats now hold all eight House seats.

Four of the five Virginia State Senate seats that include parts of the county are held by Democrats, including Democratic Sen. Jeremy Mc Pike, the President pro tempore of the Senate, Toddy Puller, George Barker and John Bell. Republican Richard Stuart also represents portions of the county.

In 2005, Democratic Gubernatorial candidate Tim Kaine won the county with 49.95% of the vote.

| Name | Party | First Election | District | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candi Mundon King | Dem | 2021 | 2 | |

| Danica Roem | Dem | 2017 | 13 | |

| Elizabeth Guzman | Dem | 2017 | 31 | |

| Dan Helmer | Dem | 2019 | 40 | |

| Michelle Maldonado | Dem | 2021 | 50 | |

| Briana Sewell | Dem | 2021 | 51 | |

| Luke Torian | Dem | 2009 | 52 | |

| John Bell | Dem | 2015 | 87 | |

| Name | Party | First Election | District | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John Bell | Dem | 2019 | 13 | |

| Richard Stuart | Rep | 2007 | 28 | |

| Jeremy McPike | Dem | 2015 | 29 | |

| Scott Surovell | Dem | 2015 | 36 | |

| George Barker | Dem | 2007 | 39 | |

National politics

Democrats hold both of the U.S. Congressional seats that include parts of Prince William County. In 2006, Democratic U.S. Senator candidate Jim Webb carried the county with 50.51% of the vote.

In the 2008 United States presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama carried Prince William with 57.51% of the vote, compared to Republican John McCain who received 41.62%. Obama's final rally the night before the election was held at the Prince William County Fairgrounds, just outside the city of Manassas.[20] He was the first Democrat to carry the county since 1964.

Continuing demographic changes in the county, such as an increasingly diverse and urbanized population, were cited by The New York Times as contributing to Obama's success in the 2012 United States presidential election and suggesting the future appeal of the Democratic Party in the United States. Between 2000 and 2010, county population had increased by 121,189 persons (43.2%).[12] It had changed from a primarily white, rural county. Prince William by 2012 had an educated professional population with the seventh-highest income in the country; it is the first county in Virginia to be composed of a majority of minorities: Hispanic, African American, and Asian. Obama and the Democrats attracted their votes.[13] Time identified Prince William as one of five critical counties in Virginia for the election. Obama defeated Romney soundly by 16 percentage points with a margin of 57%–41%,[21] narrowly beating his 2008 margin.

The county continued its trend toward Democratic candidates in the 2016 United States presidential election, Prince William County voted 57.6% for Hillary Clinton to Trump's 36.5%. Clinton's victory represented the largest margin of victory for any presidential candidate in the county since 1988. In 2020, Prince William County voted for Joe Biden with 62.6% of the vote, the largest share of the vote for a Democratic candidate since 1944.

The county has been a focal point for right-wing conspiracy theories about illegitimate votes during the 2020 presidential election.[22] Virginia conservatives cited the prosecution of Prince William County's former top election official, Michele White, for alleged vote count fraud in 2020 as evidence of election fraud concerns. However, the case was dropped,[23] and it was revealed that the errors in vote tabulation actually favored Trump, with no evidence of intentional fraud or significant impact on election outcomes.[24]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2024 | 90,203 | 39.44% | 131,128 | 57.33% | 7,381 | 3.23% |

| 2020 | 81,222 | 35.61% | 142,863 | 62.64% | 3,971 | 1.74% |

| 2016 | 71,721 | 36.51% | 113,144 | 57.60% | 11,577 | 5.89% |

| 2012 | 74,458 | 41.32% | 103,331 | 57.34% | 2,406 | 1.34% |

| 2008 | 67,621 | 41.63% | 93,435 | 57.52% | 1,390 | 0.86% |

| 2004 | 69,776 | 52.84% | 61,271 | 46.40% | 1,016 | 0.77% |

| 2000 | 52,788 | 52.52% | 44,745 | 44.52% | 2,978 | 2.96% |

| 1996 | 39,292 | 50.09% | 33,462 | 42.66% | 5,689 | 7.25% |

| 1992 | 35,432 | 46.82% | 26,486 | 35.00% | 13,762 | 18.18% |

| 1988 | 39,654 | 66.70% | 19,198 | 32.29% | 601 | 1.01% |

| 1984 | 34,992 | 68.88% | 15,631 | 30.77% | 180 | 0.35% |

| 1980 | 23,061 | 58.95% | 12,787 | 32.69% | 3,271 | 8.36% |

| 1976 | 15,446 | 49.00% | 15,215 | 48.26% | 863 | 2.74% |

| 1972 | 20,149 | 72.26% | 7,266 | 26.06% | 469 | 1.68% |

| 1968 | 7,944 | 42.51% | 5,566 | 29.79% | 5,176 | 27.70% |

| 1964 | 3,343 | 37.30% | 5,611 | 62.60% | 9 | 0.10% |

| 1960 | 2,624 | 46.53% | 2,987 | 52.97% | 28 | 0.50% |

| 1956 | 2,023 | 50.96% | 1,851 | 46.62% | 96 | 2.42% |

| 1952 | 1,619 | 49.14% | 1,653 | 50.17% | 23 | 0.70% |

| 1948 | 760 | 36.49% | 1,162 | 55.78% | 161 | 7.73% |

| 1944 | 763 | 36.20% | 1,340 | 63.57% | 5 | 0.24% |

| 1940 | 500 | 25.77% | 1,435 | 73.97% | 5 | 0.26% |

| 1936 | 457 | 23.06% | 1,512 | 76.29% | 13 | 0.66% |

| 1932 | 386 | 20.24% | 1,499 | 78.61% | 22 | 1.15% |

| 1928 | 817 | 49.73% | 826 | 50.27% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1924 | 269 | 22.99% | 847 | 72.39% | 54 | 4.62% |

| 1920 | 393 | 33.25% | 786 | 66.50% | 3 | 0.25% |

| 1916 | 192 | 20.21% | 754 | 79.37% | 4 | 0.42% |

| 1912 | 82 | 8.20% | 814 | 81.40% | 104 | 10.40% |

| 1908 | 200 | 21.07% | 738 | 77.77% | 11 | 1.16% |

| 1904 | 228 | 23.80% | 724 | 75.57% | 6 | 0.63% |

| 1900 | 680 | 33.48% | 1,351 | 66.52% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1896 | 727 | 35.00% | 1,341 | 64.56% | 9 | 0.43% |

| 1892 | 663 | 32.23% | 1,356 | 65.92% | 38 | 1.85% |

| 1888 | 740 | 35.97% | 1,313 | 63.83% | 4 | 0.19% |

| 1884 | 576 | 31.67% | 1,243 | 68.33% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1880 | 459 | 29.09% | 1,119 | 70.91% | 0 | 0.00% |

Economy

Top employers

According to the county's 2013 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[26] the top employers in the county are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Prince William County Public Schools | 1,000 and over |

| 2 | U.S. Department of Defense | 1,000 and over |

| 3 | Prince William County Government | 1,000 and over |

| 4 | Walmart | 1,000 and over |

| 5 | Morale, Welfare and Recreation | 1,000 and over |

| 6 | Sentara Healthcare | 1,000 and over |

| 7 | Wegmans Food Markets | 500 to 999 |

| 8 | Minnieland Private Day School | 500 to 999 |

| 9 | Northern Virginia Community College | 500 to 999 |

| 10 | Target Corporation | 500 to 999 |

Prince William and neighboring Loudoun County are home to millions of square feet of data centers.[27]

Education

Secondary

Prince William County Public Schools is the second largest school system in Virginia (having, circa 2007, overtaken Virginia Beach City Public Schools).[28] The system consists of 57 elementary, 16 middle, and 13 high schools, as well as a virtual high school, two traditional schools, three special education schools, and two alternative schools. The Superintendent of Prince William County Public Schools is Dr. LaTanya McDade. The system has a television station called PWCS-TV. It is programmed and operated by Prince William County Public Schools' Media Production Services Department and is accessible to Comcast and Verizon subscribers in Prince William County.

The county system serves all parts of the county except for Marine Corps Base Quantico, which is served by the Department of Defense Education Activity (DoDEA).[29] The DoDEA high school is Quantico Middle High School.

Higher

- George Mason University

- National University

- Northern Virginia Community College

- Strayer University

Catholic Schools

The Diocese of Arlington provides education from pre-K through middle school at multiple diocesan run schools,[30] and grades 9-12 at Pope John Paul the Great Catholic High School in Dumfries.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 11,615 | — | |

| 1800 | 12,733 | 9.6% | |

| 1810 | 11,311 | −11.2% | |

| 1820 | 9,419 | −16.7% | |

| 1830 | 9,330 | −0.9% | |

| 1840 | 8,144 | −12.7% | |

| 1850 | 8,129 | −0.2% | |

| 1860 | 8,565 | 5.4% | |

| 1870 | 7,504 | −12.4% | |

| 1880 | 9,180 | 22.3% | |

| 1890 | 9,805 | 6.8% | |

| 1900 | 11,112 | 13.3% | |

| 1910 | 12,026 | 8.2% | |

| 1920 | 13,660 | 13.6% | |

| 1930 | 13,951 | 2.1% | |

| 1940 | 17,738 | 27.1% | |

| 1950 | 22,612 | 27.5% | |

| 1960 | 50,164 | 121.8% | |

| 1970 | 111,102 | 121.5% | |

| 1980 | 144,636 | 30.2% | |

| 1990 | 215,686 | 49.1% | |

| 2000 | 280,813 | 30.2% | |

| 2010 | 402,002 | 43.2% | |

| 2020 | 482,204 | 20.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31]

1790–1960[32] 1900–1990[33] 1990–2000[34] 2010[35] 2020[36] | |||

2020 census

| Race / Ethnicity | Pop 2010[35] | Pop 2020[36] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 195,656 | 185,048 | 48.67% | 38.38% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 78,492 | 94,939 | 19.53% | 19.69% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 984 | 745 | 0.24% | 0.15% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 29,986 | 49,836 | 7.46% | 10.34% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 414 | 507 | 0.10% | 0.11% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 1,227 | 3,384 | 0.31% | 0.70% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (NH) | 13,783 | 26,221 | 3.43% | 5.44% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 81,460 | 121,524 | 20.26% | 25.20% |

| Total | 402,002 | 482,204 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010 census

As of the census[37] of 2010, there were 402,002 people, 137,115 housing units, and 130,785 households residing in the county. The population density was 1,186 inhabitants per square mile (458/km2). There were 137,115 housing units at an average density of 405 per square mile (156/km2). The racial makeup of the county (reporting as only one race) was:

- 57.8% White

- 20.2% Black or African American

- 0.6% Native American

- 7.5% Asian (1.5% Indian, 1.2% Filipino, 1.2% Korean, 0.8% Vietnamese 0.6% Chinese, 0.1% Japanese, 2.1% Other Asian)

- 0.1% Pacific Islander

- 9.1% from other races

- and 5.1% from two or more races

- 20.3% of the population was Hispanic or Latino of any race (6.8% Salvadoran, 3.7% Mexican, 1.8% Puerto Rican, 1.1% Guatemalan, 1.0% Peruvian, 0.9% Honduran, 0.7% Bolivian, 0.4% Colombian, 0.3% Nicaraguan, 0.3% Dominican)

Also according to census figures, there were 130,785 households in Prince William County as of April 1, 2010. According to the Census Bureau's 2009 American Community Survey,[38] 76.1% of the county's households are occupied by families, (compared to 66.5% in the United States). This represents a decrease of 4.6 percentage points since 1990, when 80.7% of households in the county were families. Approximately 42.2% of Prince William County's households are family households occupied by parents with their own children under 18 years of age.

According to the Census Bureau's 2009 American Community Survey, 29.3% of the total County population is under 18 years of age; approximately 6.5% is aged 65 and over. The median age of the population is 33.2 years. The 2009 American Community Survey also indicated that 50.0% of the county's population is male and 50.0% is female.

According to the 2009 American Community Survey, the 2009 median household income in Prince William County was $89,785. The per capita income for the county was $35,890. The 2009 American Community Survey reported that in 2009, 6.0% of Prince William County's population was living below the poverty line, including 7.7% of those under age 18 and 5.3% of those age 65 or over.

It is a majority-minority county, with "White, not Hispanic or Latino" at 44.8%, "Hispanic or Latino" at 22.3%, and "Black or African American" at 21.8% the chief groups.[39]

Sports

Northern Virginia FC is an American minor league soccer team, also located in Woodbridge, Virginia. NoVa FC has minor league affiliation with D.C. United, Washington, D.C. Major League Soccer franchise.

The historic Old Dominion Speedway was located in Manassas. Opened in 1948, it was the location of the first commercial drag race held on the East Coast, and was a stop on the NASCAR Grand National schedule in the late 50s and early 60s. Old Dominion Speedway closed in the Fall of 2012 because of noise complaints.[40]

Museums

The National Museum of the Marine Corps is located in Triangle, Virginia and is free to the public. The Historic Preservation Division of Prince William County also operates five museums: Rippon Lodge Historic Site, Brentsville Historic Centre, Bristoe Station Battlefield Heritage Park, Lucasville Historic Site, and Ben Lomond Historic Site.

Libraries

The Prince William Public Library System is a regional public library system that serves Prince William County, the City of Manassas and the City of Manassas Park. The system consists of 6 full-service branches and 5 neighborhood branches that covers the entire Prince William area.

Parks

Two National Parks lie within the county. Prince William Forest Park was established as Chopawamsic Recreational Demonstration Area in 1936 and is located in eastern Prince William County. This is the largest protected natural area in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan region at over 15,000 acres (6,070 ha). Manassas National Battlefield Park, located north of Manassas in Prince William County, preserves the site of two major American Civil War battles: the First Battle of Manassas on July 21, 1861, and the Second Battle of Manassas which was fought between August 28 and 30, 1862. Outside the South, these battles are commonly referred to as the first and second battles of Bull Run.

The Prince William County Department of Parks & Recreation operates fifty parks, two water parks, two recreation centers (Birchdale Rec. Center and Sharron Baucom Dale City Rec. Center), two community centers, six sports complexes, and an ice-skating rink:

- Prince William Forest Park, the largest National Park Service property in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area

- Leesylvania State Park, the ancestral home of the Lee family, with a range of recreational activities and views of the river

- Manassas National Battlefield Park, a Civil War battlefield

Transportation

The county is traversed by many major highways and roads, including the following:

Interstate 66

Interstate 66 Interstate 95

Interstate 95 U.S. Route 1 (Richmond Highway)

U.S. Route 1 (Richmond Highway) U.S. Route 15 (James Madison Highway)

U.S. Route 15 (James Madison Highway) U.S. Route 29 (Lee Highway)

U.S. Route 29 (Lee Highway) State Route 28 (Nokesville Road/Centerville Road)

State Route 28 (Nokesville Road/Centerville Road) State Route 55 (John Marshall Highway/Washington Street)

State Route 55 (John Marshall Highway/Washington Street) State Route 123 (Gordon Boulevard)

State Route 123 (Gordon Boulevard) State Route 215 (Vint Hill Road)

State Route 215 (Vint Hill Road) State Route 234 (Dumfries Road/Prince William Parkway/Sudley Road)

State Route 234 (Dumfries Road/Prince William Parkway/Sudley Road) State Route 234 Business (Dumfries Road/Grant Avenue/Sudley Road)

State Route 234 Business (Dumfries Road/Grant Avenue/Sudley Road) State Route 294 (Prince William Parkway)

State Route 294 (Prince William Parkway) State Route 393 (Campus Drive)

State Route 393 (Campus Drive) State Route 394 (College Drive)

State Route 394 (College Drive) State Route 612 (Yates Ford Road)

State Route 612 (Yates Ford Road) State Route 619 (Linton Hall Road/Bristow Road/Joplin Road/Fuller Heights Road)

State Route 619 (Linton Hall Road/Bristow Road/Joplin Road/Fuller Heights Road) State Route 784 (Dale Boulevard)

State Route 784 (Dale Boulevard)

Manassas Regional Airport lies near its namesake city; for commercial passengers, both Dulles Airport and Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport are located nearby.

Public bus service in the county is provided by the Potomac and Rappahannock Transportation Commission. Services provided by PRTC include OmniRide, OmniLink, and OmniMatch.

The county is served by both Virginia Railway Express (VRE) lines. The Manassas line has the Manassas Park, Manassas, and Broad Run / Airport stations. The Fredericksburg line has the Woodbridge, Rippon, and Quantico stations.[41] The Manassas, Quantico and Woodbridge stations are also served by Amtrak.

Communities

Towns

Villages

Hamlets

Census-designated places

Other unincorporated communities

Former communities

Independent cities

The independent cities of Manassas and Manassas Park are surrounded by Prince William County. Before becoming independent cities in 1975, as are all cities in Virginia, both were towns and officially part of the county. The Prince William County Circuit, District, Juvenile and Domestic Relations Courts, Prince William County Commonwealth Attorney's Office, Prince William County Adult Detention Center, Prince William County Sheriff's Office, and other county agencies are located at Prince William County Courthouse complex. The courthouse complex itself is located in a Prince William County enclave surrounded by the city of Manassas.

Prince William County, Manassas, and Manassas Park share a single judicial system (courts) and Constitutional offices (Commonwealth's Attorney, Sheriff, Circuit Court Clerk).

Notable people

- Margaret Kempe Howell, mother-in-law of Jefferson Davis

- Austin Steward, abolitionist

- Tommy Richman, rapper

Other important features

- Marine Corps Base Quantico, a large military installation

- Hylton Performing Arts Center

- Jiffy Lube Live concert venue

- Potomac Mills, a tourist destination and largest outlet mall in the region

- FBI Academy, the Federal Bureau of Investigation's training and research facility.

- Camp William B. Snyder, one of the largest Cub Scout Camps in the United States.[42]

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Prince William County, Virginia

- Prince William County Department of Fire and Rescue

- Prince William County Police Department

- Prince William County Sheriff's Office

- Splash Down Waterpark

References

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "The 20 wealthiest counties in the U.S., including these Washington, DC, suburbs: Report". Foxbusiness.com. December 18, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ Swanton, John R. (1952), The Indian Tribes of North America, Smithsonian Institution, p. 69, hdl:2027/mdp.39015015025854, ISBN 0-8063-1730-2, OCLC 52230544

- ^ Brown, George (1991). "The Indians And the Collision of Cultures". Historicprincewilliam.org. Historic Prince William, Inc. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

- ^ "Legislation creating Prince William County, Virginia". Historic Prince William. Archived from the original on April 22, 2000. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ "Commemorating the 275th anniversary of Prince William County, Virginia". Sunlight Foundation. Archived from the original on March 17, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ^ "Swifter than the Law," Washington Post, March 19, 1892, p.1

- ^ W. Fitzhugh Brundage, Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 87-92

- ^ "Mob Carries Out Death Sentence", History Engine, University of Richmond, 2008-2015

- ^ "Killing Grounds Lynchings re: Haymarket", Washington Post, July 24, 2005; accessed March 16, 2018

- ^ a b "Demographic and Economic Newsletter" Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Prince William Report, Second Quarter 2014, April–June 2014

- ^ a b Michael D. Shear (November 7, 2012). "Demographic Shift Brings New Worry for Republicans". The New York Times. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ^ Wines, Michael (November 12, 1993). "A Disneyland of History Next to the Real Thing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- ^ Powell, Elizabeth A.; Stover, Sarah (July 26, 2010). The Third Battle of Bull Run: The Disney's America Theme Park (A). Charlottesville. pp. 1–19. ProQuest 872767379.

- ^ The Disney Drawing Board – Disney's America Archived September 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Stewart, Nikita (April 5, 2006). "$17 Million Camp Pledges Cub Scout Nirvana in Va.: [FINAL Edition]". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C., United States. pp. –01. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 410008043.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Rural Crescent in Prince William County". www.pwconserve.org. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ^ Kiser, Uriah (November 1, 2008). "Thousands gathering for Obama's final rally". insidenova.com. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ "The White House – Obama's Path to Victory", Time, pp. 16–17, November 19, 2012

- ^ "Prince William elections director denounces misinformation campaign by right-wing voting group". WTOP News. October 9, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ Peters, Ben (January 11, 2024). "Judge approves dropping all charges against former Prince William registrar, canceling trial". INSIDENOVA.COM. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ Moomaw, Graham (January 11, 2024). "2020 election error in Prince William County benefited Trump, officials reveal". Virginia Mercury. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org.

- ^ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2013" (PDF). County of Prince William, Virginia. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 12, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Weisbrod, Katelyn (February 10, 2023). "In Northern Virginia, a Coming Data Center Boom Sounds a Community Alarm". Inside Climate News. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ "Northern Virginia rises to dominance". The Virginian-Pilot. Norfolk, Virginia. December 31, 2007. Archived from the original on January 3, 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Prince William County, VA" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022. - Text list - "Quantico Marine Corps Center School District" is a reference to the DoDEA as that agency operates the base schools.

- ^ "Prince William County Manassas City". www.arlingtondiocese.org. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing from 1790-2000". US Census Bureau. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ a b "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Prince William County, Virginia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Prince William County, Virginia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ American Community Survey, US Census Bureau, archived from the original on February 12, 2020, retrieved June 22, 2011

- ^ US Census Bureau. "QuickFacts Prince William County, Virginia". U.S. Department of Commerce.

White alone, not Hispanic or Latino, percent, July 1, 2015, (V2015) 44.8%, Hispanic or Latino, percent, July 1, 2015, (V2015) 22.3%. Black or African American alone, percent, July 1, 2015, (V2015) 21.8%, Asian alone, percent, July 1, 2015, (V2015) 8.7%, Two or More Races, percent, July 1, 2015, (V2015) 4.4%, American Indian and Alaska Native alone, percent, July 1, 2015, (V2015) 1.1%, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander alone, percent, July 1, 2015, (V2015) 0.2% The vintage year (e.g., V2015) refers to the final year of the series (2010 thru 2015).

[permanent dead link] - ^ "Old Dominion Speedway plans to relocate to Spotsylvania County". Business Insider. Archived from the original on February 21, 2013.

- ^ Station Map, Virginia Railway Express (VRE), archived from the original on August 10, 2009, retrieved August 9, 2009

- ^ Weimar, Carrie (May 1, 2006). "For his devotion, a Scouts honor". St. Petersburg Times. St. Petersburg, FL. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

External links

Prince William County travel guide from Wikivoyage

Prince William County travel guide from Wikivoyage- Official website

- Prince William County at the Wayback Machine (archived June 7, 2012)

- Prince William County at the Wayback Machine (archived April 12, 1997)