Presidio San Agustín del Tucsón

| Tucson Presidio | |

|---|---|

| Tucson, Arizona, United States | |

The reconstructed northeastern bastion of the Tucson Presidio in 2009 | |

| Type | Army fortification |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | |

| Condition | tourist attraction |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1775–1783 |

| Built by | |

| In use | 1776–1886 |

| Materials | Adobe, mesquite, earth |

| Battles/wars | Apache–Mexico Wars |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | |

| Occupants | |

Presidio San Agustín del Tucsón was a presidio (colonial Spanish fort) located within Tucson, Arizona, United States. The original fortress was built by Spanish soldiers during the 18th century and was the founding structure of what became the city of Tucson. After the American arrival in 1846, the original walls were dismantled, with the last section torn down in 1918. A reconstruction of the northeast corner of the fort was completed in 2007 following an archaeological excavation that located the fort's northeast tower.

History

Spanish Period

A company of Spanish Army soldiers, led by Captain Hugh O'Conor, an Irish mercenary working for Spain, selected the location of the Presidio San Agustin del Tucson on August 20, 1775. The site was on the east terrace overlooking the Santa Cruz River floodplain. Nearby was the O'odham village of Cuk Ṣon [tʃʊk ʂɔːn] at the San Agustin Mission. The name (also written S-cuk Son, Ts-iuk-shan, Tu-uk-so-on or Tuqui Son)[1][2] means "black base", referring to the base of Sentinel Peak.

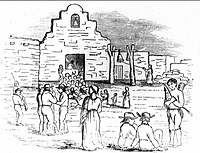

The following year, soldiers marched north from Tubac Presidio and began construction of the fort. Initially, it consisted of a scattering of buildings, some inside a wooden palisade. Mismanagement of the funds that were to be spent on adobe walls stalled their construction. A near disastrous attack by Apache raiders in June 1782 resulted in renewed efforts to complete the fort, which was accomplished in May 1783. The fort measured about 670 ft (200 m) to a side with square towers at the northeast and southwest corners. The main gate was on the center of the west wall, the presidial chapel was located along the east wall, the commandant's house was in the center, and the interior walls were lined with homes, stables, and warehouses. The massive adobe walls required constant maintenance, especially in times when attacks by Native Americans were anticipated, mostly from Apache. The fortress remained intact until the American arrival in 1856, two years after the Gadsden Treaty transferred southern Arizona to the United States. Afterward, it was rapidly dismantled, with the last standing portion torn down in 1918.

Tucson flourished under Spanish rule, but the population didn't exceed 500 until much later, when the United States controlled the city. The colony managed to grow with the help of the fort and its occupants, who launched several expeditions into Indian country to fight the Seri's, Opatas, Papago and primarily the Apache. The expeditions helped keep the natives from the area, to prevent raids on Spanish property and civilians. Throughout the Spanish period the Pimas were mostly peaceful, with the exception of two rebellions about 25 years before the Tucson Presidio was constructed. Over Tucson's history, several different Native American groups lived in the city and the down river at the villages of Tubac, Tumacacori and elsewhere. Groups of Pimas, Apaches, Papago, Oaptas, Seris, and others, all eventually lived at the Spanish settlements in the Santa Cruz River Valley. Many of the men became scouts for the Spanish Army during the wars against the native tribes. At one point the entire garrison of Fort Tubac consisted solely of Papago warriors. By the time the Spanish period ended in 1821 the old Spanish frontier settlements were being abandoned. The population of Tucson and Tubac each reached about 350 at their peaks during this time. Tumacacori had about 100 Spaniards during its peak years, and the remaining population of the forts and villages were Native American who usually outnumbered the Spanish by dozens to hundreds.

Fort Tubac was abandoned several times over 110 years due to repeated attacks at or near the fort. The garrisons remained relatively small, usually cavalry and some artillery. Lt. Juan de Olivas took command of Tucson after O'Connor from 1775 to 1777; Allande commanded the Tucson Presidio during four different attacks. He also commanded many of the advances into Apacheria and Seri country. Native warriors also contributed to the Tucson Presidio's defense several times during its history of fighting Apaches, sometimes because the natives allied with the Spanish were already long-time enemies with the Apache. The wars grew into sort of a stalemate; eventually the Spanish growth in the presidio topped off resulting in the small company size garrisons. The Spanish at any given point had fewer than 300 soldiers in all their presidios and settlements in the area. Presidio Santa Cruz de Terrenate was built along the San Pedro River southeast of Tucson in 1776, by 1780 it had already been abandoned due to Apache attacks. Presidio de San Bernardino was built just east of the present day Douglas, Arizona, in 1776 but was also abandoned in 1780. The contingents from most native groups which helped the Spanish were typically very small, about fifteen men but the Pimas contributed dozens of warriors to Captain Allande during the years who fought in most if not all of the frontier expeditions. Despite being outnumbered by the thousands, the Spanish held the majority of their settlements but could not decisively defeat the natives and stop them from raiding. Tucson became a Mexican town in 1821.

Mexican Period

When Mexico achieved its independence from Spain in 1821, the Tucson Presidio still had a Spanish garrison that accepted Mexican freedom, likely because the Spanish aristocracy's hold on northern Sonora wasn't broken as result of the war. The aristocracy supported the independence of their country which fueled the rebellion, many also led the armies that won the war. Since 1775 and even longer due to the Pima villages, Tucson has always been inhabited, unlike several other Spanish settlements in the area. During the Mexican period at least seventy-five percent of Tucson was populated by Native Americans. After independence Mexico slipped into a depression and frontier colonization quickly became under-supplied with both men and food, old alliances between Spain and the natives ended. Other tribes continued to be peaceful, the Pimas remained friendly along with Yaquis and a few other groups in southern Arizona. Apaches remained a serious threat and most of the Spanish frontier settlements in Arizona and New Mexico were abandoned and the populations fled south. Generally the Mexicans remained only in the coastal states of Texas and California, creating more Indian country in between Mexico City and California. Landlocked settlements in what is now northern New Mexico survived with Tucson and a few other mission towns such as the San Xavier and the Tumacacori Mission. Apaches continued raiding and skirmished with Mexicans just outside the Presidio several times, they raided the livestock just like they did the Spanish herds. The Mexicans were less able to defend themselves due to the depression.

By the time the war between the United States and Mexico began in 1846, the depression was over and Mexican Army forces occupied the Tucson presidio. The area was prospering and held its largest garrison of around 200 dragoons or infantrymen with two cannons. In 1846 as the United States Army's Mormon Battalion moved through present day Arizona, they nearly fought a battle with the Mexican army as they approached the fort from the southeast. The Americans were on their way to reinforce the United States Navy's campaign against California. Mormon forces captured the presidio just after the Mexican commander Captain Antonio Comaduron decided not to fight; instead he withdrew his garrison to San Xavier and then to Tubac. The Mormons eventually left Tucson and it was reoccupied by the Mexicans. The war ended with a United States victory and the Mexican Cession in which the Mexican Government sold the Americans most of what is now the southwest United States in 1848. Tucson became part of the American New Mexico Territory after the Gadsden Purchase in 1853. Though the land was purchased the Mexican garrison did not leave the Tucson Presidio until March 1856. The majority of Mexican residents remained behind.

American Period

The United States Army took control of the Tucson Presidio in 1856 after eighty-one years in existence, and the city began to thrive once more. Famous military figures, prospectors, outlaws and warriors would all become part of Tucson's culture more than ever before. With the discovery of precious minerals in the area in the 18th century by the Spanish and in the 1860s by Americans, mining camps and later mining towns were built all across the desert frontier around Tucson. From 1850 to 1920, mining camps became the center of industrialization, before agriculture and ranching provided the best opportunity of prosperity along the Santa Cruz. The period from 1870 and on is when the speed of settling the frontier became most rapid around Tucson. Most of Arizona's towns and cities were built at this time. Hostile natives remained a problem for the development of unsettled land and continued until the late 1880s. Tubac was populated by Americans just after the Mexican War. A mining company town was made of the presidio which again made Tucson a little less isolated. During the early American period, the population grew for the first several years until a major outbreak of the Apache Wars between the Chiricahuas and the American Civil War which ended up creating Arizona into the state it is today. The Chiricahua Apache were commanded by the War Chiefs Mangas Coloradas, Cochise and Geronimo. They and their allies fought primarily a guerrilla war against the remaining Mexican and new American settlements throughout the Gadsden Purchase area, all of which was considered traditional lands of the Apache. The American Indian Wars ended in Arizona, where military campaigns against Native Americans continued as late as 1918.

The great war against the Chiricahua began in 1860. After a raiding campaign into American territory against frontier settlements and the Bascom Affair in which Cochise's brother was killed, Chiricahua Apache bands began to form alliances with each other. They built an army of unknown strength which was commanded by Cochise and another chief ally, Mangas Coloradas. The Apaches then began a campaign to rid Apacheria of all the whites and Mexicans. Attacks on settlers started around what is now southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico in the Apache heartland of the Dragoon Mountains, the Dos Cabezas Mountains, the Chiricahua Mountains and Apache Pass. In the area is where the main settlers trail east and west was located. Apaches killed, captured, and tortured at least a 100 people within a year along the trail in and near Apache Pass. Hundreds more settlers were being killed elsewhere across the vast area Apaches controlled. Thousands of settlers were killed in total over the fifty years of conflict, no exact number will ever be known. Tucson was again under what was considered serious threat of attack. Apaches controlled all of the mountains around Tucson in the early 1860s, especially after the withdrawal of United States troops in 1861. Only white settlers, the remaining Tucson Mexicans, and the dwindling Pima tribe inhabited the Tucson area and the Santa Cruz Valley. Apaches were at their high point and controlled almost everywhere around the region but influence was weaker northwest of Tucson in what is now the Tohono O'odham reservation. The O'odham were generally peaceful, the Pimas are one of the larger O'odham bands as of today. When the American Civil War began, all of the forts protecting Tucson were abandoned and the Butterfield Overland Mail company closed just after. Both events left the isolated Tucson area with no military support against the Apache army.

Beginning just after the 1856 establishment of American Tucson, settlers in the southern New Mexico Territory began petitioning the government for separation. They hoped to establish a new territory in Traditional Arizona. The petitions, signed in Tucson and Mesilla, were rejected by the United States government but accepted by the Confederates. Confederate Arizona Territory south of the 34th parallel was created but did not become official until the First Battle of Mesilla in July 1861. The Apache took advantage of the withdrawal of Union troops. By then Mangas and Cochise had increased their raids and attacks on settlements so Confederate reinforcements were eventually sent to the area. Fort Tubac was besieged in August 1861 and abandoned again along with the Tumacacori mission. This left Mesilla, New Mexico and Tucson as the only major settlements in southern New Mexico Territory. Tubac's surviving populace was rescued by Tucson militia under Captain Granville H. Oury. The survivors left for Mesilla just after only to be attacked again in Cookes Canyon. Many of the male Tubacan refugees became militiamen in the Arizona Rangers and the Arizona Guards. From 1861 to 1863, several other towns were attacked by Apaches but they were usually defeated by minutemen, Confederate or Union forces. A company of Confederates under Captain Sherod Hunter reinforced the militia of Tucson in late April 1862 and held a flag raising ceremony on May 1. The company was composed primarily of militia from Doña Ana, the Arizona Rangers, of which men from Tubac had joined after escaping their town a year earlier. The rest included Texas cavalrymen, the company counted to about seventy-five men. A major Apache attack on Tucson is believed to have been thwarted due to the arrival of Captain Hunter's company.

With such a limited force of men, Hunter had orders to establish an alliance with the Native Americans in the region, particularly the Pimas. He also was directed to observe the advance of the California Column under James H. Carleton which had already begun their invasion of Confederate Arizona. Hunter dispatched several parties on foraging missions, they skirmished with Apaches twice in the Dragoon Mountains, and he sent a request to his superiors for more reinforcements. Other squads were sent to burn the Butterfield Overland Mail stations along the trail west where the Californians were advancing from. Before the Californian advance, a Union spy purchased several thousand pounds of grain and food. It was stored in the abandoned mail stations and was intended to be used by the California Column. A rebel squad under First Lieutenant Jack Swilling burned Union supplies at Stanwix Station on March 30, 1862, and skirmished with the Californians. At this time, Swilling had founded what later became Arizona's state capital of Phoenix. Rebels later fought the Battle of Picacho Pass just north of Tucson as the Union army approached the presidio. The Picacho Pass skirmish delayed Union forces for weeks after they retreated north. Finally, Union troops captured the undefended Fort Breckenridge to the northeast of Tucson and then attacked the city. The same day, the Union began their advance on Tucson. Sherod Hunter, with only about 100 men withdrew from Tucson due to the lack of reinforcements which never arrived. He left ten militiamen and Lieutenant James Henry Tevis behind to observe the Union attack. Confederate Tucson was captured without a shot fired, on May 20, 1862. James H. Carleton and his 2,000 men took command of the presidio, and the Confederates escaped to Mesilla. The Union column moved on a week or so later, and Carleton left a small garrison behind to occupy the rebel city. In 1863, with the help of Arizona's founding father, Charles D. Poston, Union Arizona Territory was created and Tucson became the capital. After the Civil War, the fortress would no longer play a direct role in warfare, though the presidio walls would continue to serve as sought-out refuge by settlers until Geronimo's surrender in 1886. Fort Lowell was built adjacent to Tucson in 1873 and became a major army post. With the end of the Apache threat, the Tucson area was rendered peaceful and the fort unnecessary.

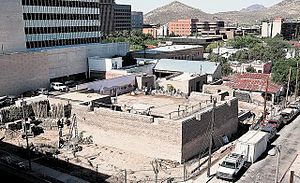

From the 1860s to 1890s Tucson would become a major stop for United States armies on campaigns to fight the Apache, hundreds of Tucson militia served in the expeditions. By the Mexican Revolution of 1910, the next war fought in southern Arizona, only one portion of the remaining four presidio walls still stood, the others were apparently buried or demolished for new development around the turn of the 20th century. The wall was three feet thick and a few feet tall. It stood in between two later American buildings and was finally destroyed in 1918. A pair of local women made a plaque which marked the location of the wall. In December 1954, a two-story boarding house was torn down to make way for a parking lot. A local business man convinced the University of Arizona to conduct an archaeological excavation. They located a 3-foot-thick (0.91 m) portion of the northeastern bastion. Attempts to have the area made into a park failed, and the parking lot was constructed.

The area was explored again by archaeologists between 2001 and 2006. Presidio-era features located there included the northeastern bastion, the east wall, soil mining pits, and trash-filled pits. Following the work, the northeastern corner of the fort was recreated as a museum, opening in 2007. Today, the Presidio San Agustin del Tucson Museum (www.TucsonPresidio.com) offers Living History Days, a variety of cultural events, and historic and cultural walking tours throughout Downtown Tucson. Other surviving portions of the Presidio wall are marked in the Old Pima County Courthouse courtyard and throughout Downtown Tucson.

Museum highlights

- Presidio San Agustin del Tucson Museum

- Presidio Tucson Museum, portion of a mural by Bill Singleton, 1972

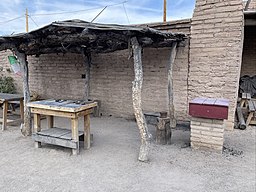

- Presidio Tucson Museum, Married Men's Quarters

- Presidio Tucson Museum, Single Men's Quarters

- The Tucson presidio solder as depicted by Bill Singleton in his mural, 1972. They dressed in heavy seven-layered deerskin armor and carried a shield of three layers of half-tanned rawhide. Their primary weapon was a nine-foot long lance.

- The presidio Tucson Blacksmith Shop. The Tucson Ring Meteorite was used for years as an anvil in the presidio blacksmith shop. The meteorite is now on display in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington D.C.

- In 1954, archaeologists from the University of Arizona discovered a Hohokam pit house underlying the Tucson Presidio.

See also

References

- ^ "25 Things You Should Know About Tucson". mentalfloss.com. 17 August 2017.

- ^ Graye, Michelle B. (2019). Greetings from Tucson: A Postcard History of the Old Pueblo. MBG. ISBN 978-0976017301 – via Google Books.

Sources

- Cooper, Evelyn S., (1995), Tucson in Focus: The Buehman Studio, Arizona Historical Society, Tucson. ISBN 0-910037-35-3.

- Tompkins, Walter A., Santa Barbara History Makers, McNally & Loftin, 1983, p. 105. ISBN 0-87461-059-1

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe, 1888, History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530–1888. The History Company, San Francisco.

- Spanish Colonial Tucson, Dobyns, Henry F., 1976, University of Arizona Press, Tucson. ISBN 0-8165-0546-2.

- Drachman, Roy P., 1999, From Cowtown to Desert Metropolis: Ninety Years of Arizona Memories, Whitewing Press, San Francisco. ISBN 1-888965-02-9