Scandals of the Ulysses S. Grant administration

Scandals of the Ulysses S. Grant administration | |

|---|---|

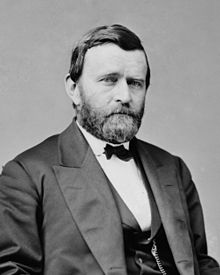

President Grant, c. 1870 | |

| 18th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hiram Ulysses Grant April 27, 1822 Point Pleasant, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | July 23, 1885 (aged 63) Wilton, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | General Grant National Memorial Manhattan, New York |

| Political party | Republican |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal 18th President of the United States Presidential campaigns

|

||

Ulysses S. Grant and his administration, including his cabinet, suffered many scandals, leading to a continuous reshuffling of officials. Grant, ever trusting of his chosen associates, had strong bonds of loyalty to those he considered friends. Grant was influenced by political forces of both reform and corruption. The standards in many of his appointments were low, and charges of corruption were widespread.[1] At times, however, Grant appointed various cabinet members who helped clean up the executive corruption. Starting with the Black Friday (1869) gold speculation ring, corruption would be discovered in seven federal departments. The Liberal Republicans, a political reform faction that bolted from the Republican Party in 1871, attempted to defeat Grant for a second term in office, but the effort failed. Taking over the House in 1875, the Democratic Party had more success in investigating, rooting out, and exposing corruption in the Grant Administration. Nepotism, although legally unrestricted at the time, was prevalent, with over 40 family members benefiting from government appointments and employment. In 1872, Senator Charles Sumner, labeled corruption in the Grant administration "Grantism."

The unprecedented way that Grant ran his cabinet, in a military-style rather than civilian, contributed to the scandals. For example, in 1869, Grant's private secretary Orville E. Babcock, rather than a State Department official, was sent to negotiate a treaty annexation with Santo Domingo. Grant never even consulted with cabinet members on the treaty annexation; in effect, the annexation proposal was already decided. A perplexed Secretary of Interior Jacob D. Cox reflected the cabinet's disappointment over not being consulted: "But Mr. President, has it been settled, then, that we want to Annex Santo Domingo?" Another instance of Grant's military-style command arose over the McGarrahan Claims, a legal dispute over mining patents in California, when Grant overrode the official opinion of Attorney General Ebenezer R. Hoar.[2] Both Cox and Hoar, who were reformers, eventually resigned from the cabinet in 1870.

Grant's reactions to the scandals ranged from prosecuting the perpetrators to protecting or pardoning those who were accused and convicted of the crimes. For example, when the Whiskey Ring scandal broke out in 1875, Grant, in a reforming mood, wrote: "Let no guilty man escape". However, when it was found out that Orville Babcock was indicted, Grant unprecedentedly testified against the government on behalf of the defendant. During his second term, Grant appointed reformers such as Benjamin Bristow, Edwards Pierrepont, and Zachariah Chandler who cleaned their respective departments of corruption. Grant finally dismissed Babcock, who was linked to several corruption charges and scandals, from the White House in 1876. It was with the encouragement of the reformers that Grant established the first Civil Service Commission, although other Republicans did not support him and the effort withered.[3][4] Grant's scandals have overshadowed his presidential achievements.[5]

Grant's temperament and character

Grant was reputedly honest about money matters. However, he trusted and protected his close associates, in denial of their guilt, despite evidence against them.[6][7] According to C. Vann Woodward, Grant had neither the training nor temperament to fully comprehend the complexities of rapid economic growth, industrialization, and western expansionism.[7][8] During his presidency, Grant enjoyed associating with men of wealth and influence, but he was also personally generous to the poor.[9] Grant often treated men of superior intelligence and ability as threats rather than assets. Instead of responding with trust and warmth to men of talent, education, and culture, he turned to his military friends from the Civil War, to his rich friends, and to politicians new as himself.[7][8] According to Grant's son, Ulysses Jr., his father was "incapable of supposing his friends to be dishonest."[10] According to Grant's Attorney General George H. Williams, Grant's "trusting heart was the weakness of his character."[11] Williams also said Grant was slow to make friends, however, once friendships were made "they took hold with hooks of steel."[11]

Many of Grant's associates were able to capture his confidence through flattery and brought their intrigues openly to his attention. One of these men, Orville E. Babcock, was a subtle and unscrupulous enemy of reformers, having served as Grant's personal secretary for seven years while living in the White House. Babcock, twice indicted, gained indirect control of whole departments of the government, planted suspicions of reformers in Grant's mind, plotted their downfall, and sought to replace them with men like himself. President Grant allowed Babcock to be a stumbling block for reformers who might have saved Grant's presidential legacy. Grant's secretary of state, Hamilton Fish, who was often at odds with Babcock, made efforts to save Grant's reputation by advocating that reformers be appointed to or kept in public office. Grant also unwisely accepted gifts from wealthy donors that cast doubts on his reputability.[7][12]

Scandals

Black Friday Gold Panic 1869

The first scandal to tar the Grant administration was Black Friday, also known as the Gold Panic, that took place in September 1869, when two aggressive private financiers attempted to corner the gold market in the New York City Gold Room, with blatant disregard to the nation's economic welfare. The scandal involved Treasury Department policy and personnel, but most of the financial damage directly affected the national economy and New York's financial houses. The intricate financial scheme was primarily conceived and administered by Wall Street manipulator Jay Gould and President Grant's brother-in-law, Abel Rathbone Corbin, who would use his personal relationship to influence the President. Gould's partner, James Fisk, joined the conspiracy later. Their plan was to convince President Grant not to sell Treasury gold, ostensibly to increase the sales of the country's agriculture products overseas, which would increase the shipping business of Fisk and Gould's Erie Railroad. Actually, they hoped to temporarily corner the gold market and make a killing. Gould and Corbin were able to get Daniel Butterfield appointed as the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury in New York City. Gould had given him a $10,000 bribe to in exchange for inside information about the Treasury Department's gold sales. On June 5, 1869, while Grant was traveling from New York to Boston on The Providence, a ship owned by Gould and Fisk, the two speculators urged Grant not to sell any gold from the Treasury and attempted to convince him that a high price of gold would help farmers and the Erie Railroad.[13] President Grant, however, was stoic and did not agree to their suggestion to stop releasing Treasury Gold into the market.[13]

Grant's Secretary of Treasury, George S. Boutwell, continued to sell Treasury gold on the open market. In late August 1869, President Grant consulted with businessman, A. T. Stewart, Grant's initial Cabinet nominee for Secretary of Treasury, concerning the Treasury's selling gold. Stewart advised Grant that the Treasury should not sell gold, in order that the Government would not be involved in the gold market.[14] Grant accepted Stewart's advice and wrote to Boutwell that selling extra Treasury gold would upset agriculture sales.[14] Boutwell had, on September 1, originally ordered $9,000,000 in gold to be sold from the Treasury in order to buy up U.S. Bonds with greenbacks. However, after receiving a letter from Grant, Boutwell canceled the order. Previously, Secretary Boutwell had been selling regularly at $1,000,000 of gold each week.[15] On September 6, 1869, Gould bought the Tenth National Bank, which was used as a buying house for gold, and Gould and Fisk then began buying gold in earnest. As the price of gold began to rise, Grant became suspicious of possible manipulation and wrote a letter to Secretary Boutwell on September 12, stating "The fact is, a desperate struggle is now taking place...I write this letter to advise you of what I think you may expect, to put you on your guard." However, President Grant's personal associations with Gould and Fisk gave them the clout that they needed to continue their financial scam on Wall Street.[16][17][18]

Sometime around September 19, 1869, Corbin, at the urging of Gould, sent a letter to Grant desperately urging him not to release gold from the Treasury. Grant received the letter from a messenger while playing croquet with Porter at the mansion of Grant's kinsman in Washington, Pennsylvania. He finally realized what was going on and was determined to stop the gold manipulation scheme. When pressed for a reply to Corbin's letter, Grant responded curtly that everything was "all right" and that there was no reply. One Grant biographer described the comical nature of the events as an "Edwardian farce." Grant, however, did have his wife Julia respond in a letter giving advance warning to Grant's sister and recommending that her husband Abel Corbin needed to get out of the gold speculation market. When Gould visited Corbin's house, he read the letter from Mrs. Grant containing the warning from Grant, after which he began to sell gold, while also buying small amounts of gold in order to keep people from getting suspicious. Gould never told Fisk, who kept buying gold in earnest, that Grant was catching onto their predatory scheme.[19]

Secretary Boutwell was already keeping track of the situation and knew that the profits made in the manipulated rising gold market could ruin the nation's economy for several years. By September 21 the price of gold had jumped from $137 to $141, and Gould and Fisk jointly owned $50 million to $60 million in gold. Boutwell and Grant finally met on Thursday, September 23, and agreed to release gold from the treasury if the gold price kept rising. Grant wanted $5,000,000 in gold to be released while Boutwell wanted $3,000,000 released. Then, on (Black) Friday, September 23, 1869, when the price of gold had soared to $160 an ounce, Boutwell released $4 million in gold specie into the market and bought $4,000,000 in bonds. Boutwell had also ordered that the Tenth National Bank be closed on the same day. The gold market crashed and Gould, Corbin, and Fisk were foiled, while many investors were financially ruined.[16]

The gold panic devastated the United States economy for months. Stock prices plunged and the price of food crops such as wheat and corn dropped severely, devastating farmers who did not recover for years afterward. Gould had earlier claimed to Grant that raising the price of gold would actually help farmers. Also Fisk refused to pay off many of his investors who had bought gold on paper. The volume of stocks being sold on Wall Street decreased by 20%. Fisk and Gould, who could afford to hire the best lawyers, were never held accountable for their profiteering, as favorable judges declined to prosecute. Gould remained a powerful force on Wall Street for the next 20 years. Fisk, who practiced a licentious lifestyle, was killed by a jealous rival on January 6, 1872.[16] Butterfield later resigned.

In an 1870 Congressional investigation into the gold panic, Democrats on the House investigation committee questioned why Julia Grant had received a package from the Adams Express Company containing money reported to be $25,000. The company ledger was brought in as evidence and initially appeared to corroborate this. The story agreed upon by the company executive and the Republicans on the committee was that the package was really just $250.00. Nonetheless, it was highly unusual for a First Lady to receive cash in the mail. Corbin had bought gold at 133 margin and sold at 137, leaving Julia a profit of $27,000. Neither Mrs. Grant nor Mrs. Corbin testified in front of the investigation committee. In 1876 Secretary of State Hamilton Fish revealed to Grant that Orville E. Babcock, another private secretary to the President, had also been involved in gold speculations in 1869.[20][21]

New York custom house ring

In 1871, the New York Custom House collected more revenue from imports than any other port in the United States. By 1872, two congressional investigations and one by the Treasury Office under Secretary George S. Boutwell looked into allegations of a corruption ring set up at the New York Custom House under two Grant collector appointments, Moses H. Grinnell and Thomas Murphy. Both Grinnell and Murphy allowed private merchants to store goods not claimed on the docks in private warehouses for exorbitant fees. Grant's secretaries Horace Porter and Orville E. Babcock and Grant's friend George K. Leet, owner of a private warehouse, allegedly shared in these profits. Secretary Boutwell advocated a reform to keep imports on company dock areas rather than being stored at designated warehouses in New York. Grant's third collector appointment, Chester A. Arthur, implemented Boutwell's reform. On May 25, 1870, Boutwell had implemented reforms that reduced public cartage and government costs, stopped officer gratuities, and decreased port smuggling, but on July 2, 1872, U.S. Senator Carl Schurz insinuated in a speech that no reforms had been undertaken and that the old abuses at the custom-house continued. The New York Times claimed that Schurz's speech was "carefully prepared" and "more or less disfigured and discolored by error." The second thorough congressional investigation concluded that abuses either did not exist, had been corrected, or were in the process of being corrected.[22]

Star Route ring

In the early 1870s, lucrative postal route contracts were given to local contractors on the Pacific coast and southern regions of the United States. These were known as "Star Routes" because an asterisk was placed on official Post Office documents. These remote routes were hundreds of miles long and went to the most rural parts of the United States by horse and buggy. Previously inaccessible areas on the Pacific coast received weekly, semi-weekly, and daily mail because of these routes. However, corruption ensued, with contractors paid exorbitant fees for fictitious routes and for providing low-quality postal service to the rural areas.

One contractor, F.P. Sawyer, made $500,000 a year on routes in the Southwest.[23][24] To obtain these highly prized postal contracts, contractors, postal clerks, and various intermediary brokers set up an intricate ring of bribery and straw bidding in the Postal Contract Office. Straw bidding reached a peak under Postmaster General John Creswell, who was exonerated by an 1872 congressional investigation that was later revealed to have been tainted by a $40,000 bribe from western postal contractor Bradley Barlow. An 1876 Democratic investigation was able to temporarily shut down the ring, but it reconstituted itself and continued until a federal trial in 1882, under President Chester A. Arthur, finally shut down the Star Route ring.[23][24] The conspirators, however, who were indicted and prosecuted, escaped conviction in both their first and second trials.

Salary grab

On March 3, 1873, President Grant signed a law that increased the president's salary from $25,000 a year to $50,000 a year. The law raised salaries of members of both houses of the United States Congress from $5,000 to $7,500. Although pay increases were constitutional, the act was passed in secret with a clause that gave the congressmen $5,000 in bonus payouts for the previous two years of their terms. The Sun and other newspapers exposed the $5,000 bonus clause to the nation. The law was repealed in January 1874 and the bonuses were returned to the treasury.[25] This pay raise proposal was submitted as an amendment to the government's general appropriations bill. Had Grant vetoed the bill, the government would not have any money to operate for the following fiscal year, which would have necessitated a special session of Congress. However, Grant missed an opportunity to make a statement by threatening a veto.[26] Public outcry prompted Congress to rescind the congressional raise, however the presidential salary increase remained, the president's salary having been unchanged since George Washington's presidency more than 80 years before.[27]

Sanborn incident

In 1874, Grant's cabinet reached its lowest ebb in terms of public trust and qualified appointments. After the presidential election of 1872, Grant reappointed all of his Cabinet with a single exception. Charges of corruption were rife, particularly from The Nation, a reliable journal that was going many of Grant's cabinet members. Treasury Secretary George S. Boutwell had been elected to the U.S. Senate in the 1872 election and was replaced by Assistant Treasury Secretary William A. Richardson in 1873. Richardson's tenure as Treasury Secretary was very brief, as another scandal erupted. The government had been known to hire private citizens and groups to collect taxes for the Internal Revenue Service.[28][29] This moiety contract system, although legal, led to extortion abuse in the loosely run Treasury Department under Sec. Richardson.[30][31]

John B. Sanborn was contracted by Sec. Richardson to collect certain taxes and excises that had been illegally withheld from the government; having received an exorbitant moiety of 50% on all tax collections.[30][31] Treasury officials pressured Internal Revenue agents not to collect delinquent accounts so Sanborn could accumulate more. Although the collections were legal, Sanborn reaped $213,000 in commissions on $420,000 taken in taxes. A House investigation committee in 1874 revealed that Sanborn had split $156,000 of this with unnamed associates as "expenses." Although Richardson and Senator Benjamin Butler were suspected to have taken a share of the profit money, there was no paper trail to prove such transactions, and Sanborn refused to reveal with whom he split the profits. While the House committee was investigating, Grant quietly appointed Richardson to the Court of Claims and replaced him with the avowed reformer Benjamin H. Bristow.[32] On June 22, 1874, President Grant, in an effort of reform, signed a bill into law (Anti-Moiety Acts) that abolished the moiety contract system.[30]

Department of Interior

In 1875, the U.S. Department of the Interior, excluding Yellowstone, was in serious disrepair, due to corruption and incompetence. Interior Secretary Columbus Delano, who allowed profiteering to thrive in the department, was forced to resign from office on October 15, 1875. Delano had also given lucrative cartographical contracts to his son John Delano and Ulysses S. Grant's own brother, Orvil Grant. Neither John Delano nor Orvil Grant performed any work, nor were they qualified to hold such surveying positions.[33][34]

On October 19, 1875, Grant made another reforming cabinet choice when he appointed Zachariah Chandler as Secretary of the Interior. Chandler immediately went to work reforming the Interior Department by dismissing all the unimportant clerks in the Patent Office. Chandler had discovered that during Delano's tenure, money had been paid to fictitious clerks while other clerks had been paid without performing any services. Chandler next turned to the Department of Indian Affairs to reform another Delano debacle. President Grant ordered Chandler to fire everyone, saying, "Have those men dismissed by 3 o'clock this afternoon or shut down the bureau." Chandler did exactly as Grant had ordered. Chandler also banned bogus agents, known as "Indian Attorneys," who had been paid $8.00 a day plus expenses for, ostensibly, providing tribes with representation in the nation's capital. Many of these agents were unqualified and swindled the Native American tribes into believing they had a voice in Washington.[35]

Department of Justice

Attorney General George H. Williams administered the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) with slackness. There were rumors that Williams was taking bribes in exchange for declining to prosecute pending trial cases. In 1875, Williams was supposed to prosecute the merchant house Pratt & Boyd for fraudulent customhouse entries. The Senate Judiciary Committee had found that Williams had dropped the case after his wife had received a $30,000 payoff. When informed of this, Grant forced Williams's resignation. Williams had also indiscreetly used Justice Department funds to pay for carriage and household expenses.[36][37]

Whiskey Ring

The worst and most famous scandal to hit the Grant administration was the Whiskey Ring of 1875, exposed by Treasury Secretary Benjamin H. Bristow and journalist Myron Colony. Whiskey distillers had been evading taxes in the Midwest since the Lincoln Administration.[38] Distillers of whiskey bribed Treasury Department agents who in turn aided the distillers in evading taxes to the tune of up to $2 million per year. The agents would neglect to collect the required excise tax of 70 cents per gallon and then split the illegal gains with the distillers. The ringleaders had to coordinate distillers, rectifiers, gaugers, storekeepers, revenue agents, and Treasury clerks by recruitment, impressment, and extortion.[39][40]

On January 26, 1875, Bristow ordered Internal Revenue officers in various sites to different locations, effective February 15, 1875, on a suggestion from Grant. This would keep the fraudulent officers off guard and allow investigators to uncover their misdeeds. Grant later rescinded the order on the grounds that advance notice would cause the ringleaders to cover their tracks and become suspicious.[41] Rescinding Secretary Bristow's order would later give rise to a rumor that Grant was interfering with the investigation. Although moving the supervisors most certainly would have disrupted the ring, Bristow conceded that he would need documentary evidence on the ring's inner workings to prosecute the perpetrators. Bristow, undaunted, kept investigating and found the ring's secrets by sending Myron Colony and other spies to gather whiskey shipping and manufacturing information.[39]

On May 13, 1875, with Grant's endorsement, Bristow struck hard at the ring, seized the distilleries, and made hundreds of arrests. The Whiskey Ring was broken. Bristow, with the cooperation of Attorney General Edwards Pierrepont and Treasury Solicitor Bluford Wilson, launched proceedings to bring many members of the ring to trial. Bristow had obtained information that the Whiskey Ring operated in Missouri, Illinois, and Wisconsin. Missouri Revenue Agent John A. Joyce and two of Grant's appointees, Supervisor of Internal Revenue General John McDonald and Orville E. Babcock, the private secretary to the President, were eventually indicted in the Whiskey Ring trials.[42] Grant's other private secretary Horace Porter was also involved in the Whiskey Ring according to Solicitor General Bluford Wilson.[43]

Special prosecutors appointed

Grant then appointed a special prosecutor, former senator John B. Henderson, to go after the ring. Henderson, while in the Senate, had been the administration's worst critic, and Grant appointed him to maintain integrity in the Whiskey Ring investigation. Henderson convened a grand jury, which found that Babcock was one of the ringleaders. Grant received a letter to this effect, on which he wrote, "Let no guilty man escape."[44] It was discovered that Babcock sent coded letters to McDonald on how to run the ring in St. Louis. During the investigation, McDonald claimed he gave Babcock $25,000 from the divided profits and even personally sent him a $1,000 bill in a cigar box.[44]

After Babcock's indictment, Grant requested that Babcock go through a military trial rather than a public trial, but the grand jury denied his request. In a reversal of his "let no guilty man escape," order to Sec. Bristow, Grant unexpectedly issued an order not to give any more immunity to persons involved in the Whiskey Ring, leading to speculation that he was trying to protect Babcock. Although this reversal had the appearance of not letting the guilty getaway, the prosecutor's trial cases were made more difficult to prove in court. The order caused strife between Sec. Bristow and Grant, since Bristow needed distillers to testify with immunity in order to pursue the ringleaders.[38] Prosecutor Henderson, himself, while going after members of the ring in court accused Grant of interfering with Secretary Bristow's investigation.[45] accusation angered Grant, who fired Henderson as special prosecutor. Grant then replaced Henderson with James Broadhead. Broadhead, though a capable attorney, had little time to get acquainted with the facts of Babcock's case and those of other Whiskey Ring members. At the trial, a deposition was read from President Grant stating that he had no knowledge that Babcock was involved in the ring. The jury listened to the president's words and quickly acquitted Babcock of any charges. Broadhead went on to close out all the other cases in the Whiskey Ring.[45] McDonald and Joyce were convicted in the graft trials and sent to prison. On January 26, 1877, President Grant pardoned McDonald.[39]

President Grant's deposition

The Whiskey Ring scandal even came to the steps of the White House. There were rumors that Grant himself was involved with the ring and was diverting its profits to his 1872 re-election campaign. Grant needed to clear his own name as well as Babcock's. Earlier, Grant had refused to believe Babcock was guilty even when Bristow and Wilson personally presented him with damaging evidence, such as two telegrams signed "Sylph"; Babcock suggested that the signature was that of a woman giving the president "a great deal of trouble", hoping that Wilson would back off for fear of igniting a presidential sex scandal, but Wilson was not bluffed.[46]

On the advice of Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, the President did not testify in open court but instead gave a deposition in front of a congressional legal representative at the White House. Grant was the first and, to date, the only president ever to testify for a defendant. The historic testimony came on Saturday, February 12, 1876. Chief Justice Morrison R. Waite, a Grant appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court, presided over the deposition.[39] The following are excerpts from President Grant's deposition.

- Eaton: "Have you ever seen anything in the conduct of General Babcock, or has he ever said anything to you, which indicated to your mind that he was in any way interested in or concerned with the Whiskey Ring at St. Louis or elsewhere?"

- President Grant: "Never."[41]

- Eaton: "Did General Babcock on or about April 23, 1875, show you a dispatch in these words: "St. Louis, April 23, 1875. Gen. O.E. Babcock, Executive Mansion, Washington, D.C. Tell Mack to see Parker of Colorado; & telegram to Commissioner. Crush out St. Louis enemies."

- Cook: "Objection." Made for the record.

- President Grant: "I did not remember about these dispatches at all until since the conspiracy trials have commenced. I have heard General Babcock's explanation of most or all of them since that. Many of the dispatches may have been shown to me at the time, and explained, but I do not remember it."

- Eaton: "Perhaps you are aware, General, that the Whiskey Ring have persistently tried to fix the origins of that ring in the necessity for funds to carry on political campaigns. Did you ever have intimation from General Babcock, or anyone else in any manner, directly or indirectly, that any funds for political purposes were being raised by any improper methods?"

- Cook: "Objection." Made for the record.

- President Grant: "I never did. I have seen since these trials intimations of that sort in the newspapers, but never before."

- Eaton: "Then let me ask you if the prosecuting officers have not been entirely correct in repelling all insinuations that you ever had tolerated any such means for raising funds."

- Cook: "Objection." Made for the record.

- President Grant: "I was not aware that they had ever attempted to repel any insinuations."[39]

On February 17, 1876, U.S. Circuit Justice John F. Dillon, another Grant appointment, overruled Cook's objections, declaring the questions admissible in court. Grant, who was known for a photographic memory, had many uncharacteristic lapses when it came to remembering incidents involving Babcock. The deposition strategy worked and the Whiskey Ring prosecution never went after Grant again. During Babcock's trial in St. Louis the deposition was read to the jury. Babcock was acquitted at trial. After the trial, Grant distanced himself from Babcock. After the acquittal, Babcock initially returned to his position as Grant's private secretary outside the President's office. At public outcry and the objection of Hamilton Fish, Babcock was dismissed as private secretary and focused on another position that he had been given by Grant in 1871: superintending engineer of public buildings and grounds.[39][42]

Grant's Pulitzer Prize winning biographer, William S. McFeely, stated that Grant knew Babcock was guilty and perjured himself in the deposition. According to McFeely, the "evidence was irrefutable" against Babcock, and Grant knew this. McFeely also points out that John McDonald also stated that Grant knew that the Whiskey Ring existed and perjured himself to save Babcock. Grant historian Jean Edward Smith counters that evidence against Babcock was "circumstantial" and the St. Louis jury acquitted Babcock "in the absence of adequate proof." More recently, (2017) historian Charles Calhoun and author of "The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant" concludes correspondence between Babcock and his lawyers "leaves little doubt of Babcock's complicity in the Whiskey Ring."[47]

Many of Grant's friends who knew him claimed that the President was "a truthful man" and it was "impossible for him to lie." Yet Treasury Clerk A. E. Willson told future Supreme Court Justice John Harlan, "What hurt Bristow most of all and disheartened him is the final conviction that Grant is himself in the Ring and knows all about [it]"[48] Grant's popularity, however, decreased significantly in the country as a result of his testimony and after Babcock was acquitted in the trial. Grant's political enemies used this deposition as a launchpad to public office. The New York Tribune stated that the Whiskey Ring scandal "had been met at the entrance of the White House and turned back." However, the national unpopularity of Grant's testimony on behalf of his friend Babcock ruined any chances for a third term nomination.[49][50][51]

Bristow's investigation results

When Secretary Benjamin Bristow struck suddenly at the Whiskey Ring in May 1875, many people were arrested and the distilleries involved in the scandal were shut down. Bristow's investigation resulted in 350 federal indictments. There were 110 convictions, and three million dollars in tax revenues were recovered from the ring.[37][49][52]

Trader Post ring

Grant had no time to recover after the Whiskey Ring graft trials ended, for another scandal erupted involving War Secretary William W. Belknap. A Democratic House investigation committee revealed that Belknap had taken money in exchange for an appointment to a lucrative Native American trading post. In 1870, responding to extensive lobbying by Belknap, Congress had authorized the Secretary of War, to award private trading post contracts to military forts throughout the nation.[53] Native Americans would come into the forts and trade for food, weapons, and clothing. Additionally, U.S. soldiers stationed at the forts purchased costly supplies. Both Indians and soldiers generated huge profits at the trading posts. The profit money from Fort Sill was shared by Belknap and his wives, in order for the Belknap's to live an extravagant Washington D.C. lifestyle.

Belknap's wife Carrie, with Belknap's authority and approval, managed to secure a private trading post at Fort Sill for a personal friend from New York City, Caleb P. Marsh. An illicit contract arrangement was set up by Belknap, between Carrie Belknap, Caleb P. Marsh, and incumbent contract holder John S. Evans, in which Carrie Belknap and Marsh would receive $3,000 every quarter, splitting the proceeds, while Evans would be able to retain his post at Fort Sill. Carrie Belknap died within the year, but Belknap and his second wife continued to accept payments, though they were smaller due to a dip in Fort Sill's profits, after the Panic of 1873. By 1876 Belknap had received $20,000 from the illicit arrangement. On February 29, 1876, Marsh testified in front of a House investigation committee headed by Representatives Lyman K. Bass and Hiester Clymer. During the testimony, Marsh testified that Belknap and both his wives had accepted money in exchange for the lucrative trading post at Fort Sill. The scandal was particularly upsetting, in this Victorian age, since it involved women.[54][55] Lieut. Col. George A. Custer later testified to the Clymer Committee on March 29 and April 4 that Sec. Belknap had received kickback money from the profiteering scheme of post traders through the resale of food meant for Indians.[56]

On March 2, 1876, Grant was informed by Benjamin Bristow at breakfast of the House investigation against Secretary Belknap. After hearing about Belknap's predicament, Grant arranged a meeting with Representative Bass about the investigation. However, Belknap, escorted by Interior Secretary Zachariah Chandler, rushed to the White House and met with Grant before his meeting with Representative Bass. Belknap appeared visibly upset or ill, mumbling something about protecting his wives' honor and beseeching Grant to accept his resignation "at once." Grant, in a hurry to get to a photography studio for a formal portrait, agreed and accepted Belknap's resignation without reservation.[55]

Grant historian Josiah Bunting III noted that Grant was never put on his guard when Secretary Belknap came to the White House in a disturbed manner or even asked why Belknap wanted to resign in the first place. Bunting argues that Grant should have pressed Belknap into an explanation for the abrupt resignation request.[57] Grant's acceptance of the resignation indirectly allowed Belknap, after he was impeached by the House of Representatives for his actions, to escape conviction since he was no longer a government official. Belknap was acquitted by the Senate, escaping with less than the two-thirds majority vote needed for conviction. Even though the Senate voted that it could put private citizens on trial, many senators were reluctant to convict Belknap since he was no longer Secretary of War. It has been suggested that Grant accepted the resignation in a Victorian impulse to protect the women involved.[54]

Cattellism

(1869–1877)

Congress allotted Secretary George M. Robeson's Department of the Navy $56 million for construction programs. In 1876, a congressional committee headed by Representative Washington C. Whitthorne discovered that $15 million of that sum was unaccounted for. The committee suspected that Robeson, who was responsible for naval spending, embezzled some of the missing money and laundered it in real estate transactions. This allegation remained unproven by the committee.[58]

The main charge against Robeson was taking financial favors from Alexander Cattell & Co., a grain contractor, in exchange for giving the company profitable contracts from the Navy. An 1876 Naval Affairs committee investigation found Robeson to have received such gifts as a team of horses, Washington real estate, and a $320,000 vacation cottage in Long Branch, New Jersey, from Alexander Cattell & Company. The same company also paid off a $10,000 note that Robeson owed to Jay Cooke and offered itself as an influence broker for other companies doing business with the Navy, thus turning away any competitive bidding for naval contracts. Robeson was also found to have $300,000 in excess to his yearly salary of $8000. The House Investigation committee had searched the disorganized books of Cattell, but found no evidence of payments to Robeson. Without enough evidence for impeachment, the House ended the investigation by admonishing Robeson for gross misconduct and claimed that he had set up a system of corruption known as Cattellism.[59][60]

In a previous investigation that Charles Dana headed in 1872, Robeson had been suspected of awarding a $93,000 bonus to a building contractor in a "somewhat dangerous stretch of official authority" known as the Secor claims. A competent authority claimed that the contractor had already been paid in full and there was no need for further reward. Robeson was also charged with awarding contracts to shipbuilder John Roach without public bidding. The latter charge proved to be unfounded. The close friendship with Daniel Ammen, Grant's longtime friend growing up in Georgetown, Ohio, helped Robeson keep his cabinet position.[58][59]

On March 18, 1876, Admiral David D. Porter wrote a letter to William T. Sherman, "...Our cuttle fish [Robeson] of the navy although he may conceal his tracks for a while in the obscure atmosphere which surrounds him, will eventually be brought to bay...." Robeson later testified in front of a House Naval Committee on January 16, 1879, about giving contracts to private companies. Robeson was asked about the use of old material to build ironclads and whether he had the authority to dispose of the Puritan, an outdated ironclad. Although Robeson served ably during the Virginius Affair and did authorize the construction of five new Navy ships, his financial integrity remained in question and was suspect during the Grant administration. To be fair, Congress gave Robeson limited funding to build ships and as Secretary was constantly finding ways to cut budgets.[58][59]

Safe burglary conspiracy

In September 1876, Orville E. Babcock was involved in another scandal.[61] Corrupt building contractors in Washington, D.C., were on trial for graft when bogus Secret Service agents working for the contractors placed damaging evidence into the safe of the district attorney who was prosecuting the ring. On the night of April 23, 1874, hired thieves opened the safe, using an explosive to make it appear that the safe had been broken into. One of the thieves then took the fake evidence to the house of Columbus Alexander, a citizen who was active in prosecuting the ring.[62] The corrupt agents "arrested" the "thieves" who then committed perjury by signing a document falsely stating Alexander was involved in the safe burglary.

The conspiracy came apart when two of the thieves turned state evidence and Alexander was exonerated in court. Babcock was named as part of the conspiracy, but later acquitted in the trial against the burglars; evidence suggests that the jury had been tampered with.[38] Evidence, which we cannot produce, also suggests that Babcock was involved with the swindles by the corrupt Washington contractors' ring and with those who wanted to get back at Columbus Alexander, an avid reformer and critic of the Grant Administration. In 1876 Grant dismissed Babcock from the White House under public pressure due to Babcock's unpopularity. Babcock continued in government work and became Chief Light House Inspector. In 1883, Babcock drowned at sea at the age of 48 while supervising the building of Mosquito Inlet Light station.[63]

Lakota treaty breach

The breach of a treaty between the Lakotas and the United States, signed in 1868, the year before Grant took office, was engineered by Grant and his cabinet, in February 1876, in order to accommodate miners seeking gold in the Black Hills. Known as the Paha Sapa (literally, "hills that are black"), this area was essential to the survival of the Lakota living in the Unceded Territory (versus those living on the Great Sioux Reservation), as a game reserve.[64]

Scandal summary table

| Scandal | Description | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Black Friday | Speculators tied to Grant corner the gold market and ruin the economy for several years. | 1869 |

| New York custom house ring | Alleged corruption ring at the New York Custom House under two of Grant's appointees. | 1872 |

| Star Route postal ring | Corrupt system of postal contractors, clerks, and brokers to obtain lucrative Star Route postal contracts. | 1872 |

| Salary grab | Congressmen receive a retroactive $5,000 bonus for previous term served. | 1872 |

| Breach of Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) | Organized a White House cabal to plan a war against the Lakotas to allow mining of gold found in Black Hills. | 1874 |

| Sanborn moiety extortion | John Sanborn charged exorbitant commissions to collect taxes and split the profits among associates. | 1874 |

| Secretary Delano's Department of Interior | Interior Secretary Columbus Delano allegedly took bribes in exchange for fraudulent land grants. | 1875 |

| U.S. Attorney General Williams' DOJ | Attorney General George H. Williams allegedly received a bribe not to prosecute the Pratt & Boyd company. | 1875 |

| Whiskey Ring | Corrupt government officials and whiskey makers steal millions of dollars in a national tax evasion scam. | 1876 |

| Secretary Belknap's Department of War | War Secretary William Belknap allegedly takes extortion money from trading contractor at Fort Sill. | 1876 |

| Secretary Robeson's Department of Navy | Secretary of Navy George Robeson allegedly receives bribes from Cattell & Company for lucrative Navy contracts. | 1876 |

| Safe Burglary Conspiracy | Private Secretary Orville Babcock indicted over framing a private citizen for uncovering corrupt Washington contractors. | 1876 |

Scandal cabinet and appointees

The most infamous of Grant's cabinet or other presidential appointees who were involved in scandals or criminal activity:

- Daniel Butterfield, Assistant Secretary of Treasury – (Black Friday- 1869)(Forced to resign by Grant.)

- William A. Richardson, Secretary of Treasury – (Sanborn Contracts- 1874)(Resigned and appointed Federal Judge by Grant.)

- George H. Williams, Attorney General – (Pratt & Boyd- 1875)(Resigned)

- Columbus Delano, Secretary of Interior – (Bogus Agents – 1875)(Resigned)

- Orville E. Babcock, Private Secretary who worked daily with Grant in the Oval Office, wielded unprecedented influence and at times was able to thwart the efforts of reformers. – (Black Friday – 1869) (Whiskey Ring – 1875) (Safe Burglary Conspiracy – 1876) (Acquitted in Saint Louis Whiskey Ring trials by jury due to Grant's defense testimony in his favor.)

- John McDonald, Internal Revenue Supervisor, St. Louis – (Whiskey Ring– 1875) (Indicted and convicted; served prison time; claimed Grant was involved in the Whiskey Ring but did not supply any evidence.)

- Horace Porter, Private Secretary – (Whiskey Ring – 1875)

- William W. Belknap, Secretary of War – (Trading Post Ring- 1876) (Resigned; Convicted by House; acquitted by Senate; indictments against Belknap in Washington D.C. court were dropped by the judge at the request of Grant and Attorney General Alphonso Taft.)

- George M. Robeson, Secretary of Navy – (Naval Department Ring- 1876) (Grant defended Robeson in State of the Union address. Grant believed Robeson had kept U.S. Navy as modern as possible during his lengthy tenure.)

Nepotism

Grant was accused by Senator Charles Sumner in 1872 of practicing nepotism while President. Although the practice of the U.S. president's appointing family members to executive or White House office was not legally restricted until 1967,[65] there was a potential for profiteering and widespread abuse. Grant's cousin Silas A. Hudson was appointed minister to Guatemala. His brother-in-law Reverend M.J. Cramer was appointed as consul at Leipzig. Mrs Grants brother-in-law James F. Casey was given the position of Collector of Customs in New Orleans, Louisiana where he made money by stealing fees. Frederick Dent, another brother-in-law was the White House usher and made money giving out insider information. In all, it is estimated that 40 relatives somehow financially prospered indirectly while Grant was President.[33] Six 19th Century Presidents, including Grant, appointed family members to executive or White House office.[65] The other five 19th Century Presidents include: James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, John Tyler, and James Buchanan.[65]

Democratic Party Tweed Ring

The Democratic Party in New York, during Grant's presidency, was not free of corruption charges or scandal. During the 1860s and 1870s Democratic Party "Boss" Tweed, in New York, ran an aggressive political machine, bribing votes, fixing judges, stole millions in contracts, while controlling New York politics. Opponents of the ring, including Grant's future Attorney General, Edwards Pierrepont,[66] part of the Committee of Seventy, ran the Tweed Ring out of office in the November 1871 elections. Democratic Party leader Samuel J. Tilden, and future 1876 presidential candidate, played a major part in breaking the Tweed Ring.[67] Members of the Tweed Ring, including Tweed, were put on trial and sent to prison. Tweed escaped in 1875 and fled to Cuba and Spain. Tweed was arrested in Spain and extradited back to the United States, on November 23, 1876, where he served out his sentence in prison until his death in 1878.[68][69]

Liberal Republican revolt

In March 1871, dissatisfied Republicans questioned whether Grant was worthy of a second nomination. Calling themselves Liberal Republicans, party leaders, including Senator Carl Schurz (Missouri), and Grant's former Secretary of Interior Jacob D. Cox, broke away from the standard Republican Party. The Liberal Republicans demanded principled reform and amnesty to white former Confederates. Schurz was against "Negro supremacy" in the South and wanted to restore the white rule in the state governments. The movement was a "cautious blend of progressive and reactionary impulses".[70] To defeat Grant, the Liberal Republicans nominated Horace Greely for the presidency. However, Grant, who remained popular, easily won reelection. Grant believed he was vindicated. [71]

Legacy and historical reputation

The nation and the constitution survived the rising tide of financial and political corruption during President Grant's two terms in office from 1869 to 1877. With slavery no longer the clear moral issue for the American people, and absent the dynamic leadership of Abraham Lincoln taken by an assassin's bullet, the nation for a while floundered in the seas of financial and political indulgence. The high-water mark of the flood of corruption that swept the nation took place in 1874 after Benjamin Bristow was put in charge to reform the Treasury. In 1873, Grant's friend and publisher, Mark Twain, along with coauthor Charles Dudley Warner, in a work of fiction, called this American era of speculation and corruption the Gilded Age. Between 1870 and 1900, the United States population nearly doubled in size, gainful employment increased by 132 percent, and nonfarm labor constituted 60 percent of the workforce.[72][73][74]

Inevitably, Grant's low standards in cabinet appointments, and his readiness to cover for associates or friends involved in condemnable behavior, defied the popular notion of a government free of corruption and favoritism. Stemming the flood of corruption that swept the nation during Grant's presidency and the Reconstruction period would have required the strength of a moral giant in the White House. Grant was no moral giant. In fairness, the booming economy that proceeded after the Civil War enveloped the whole nation in a chaotic frenzy for achieving financial gain and success. The caricature and cliché of the Grant Presidency is eight years of political plundering and that little was accomplished. Grant, however, was committed to completing the unification of a bitterly divided country torn by Civil War, to honor Abraham Lincoln, and give full citizenship rights to African Americans and their posterity.[7][74][75]

An analysis of the scandals reveals the many powers at Grant's disposal as the President of the United States. His confidants knew this and in many situations took advantage of Grant's presidential authority. Having the ability to pardon, accept resignations, and even vouch for an associate in a deposition, created an environment difficult, though not impossible, for reformers in and outside of the Grant Administration. Grant himself, far from being politically naive, had played a shrewd hand at times in the protection of cabinet and appointees. Examples include not allowing Benjamin Bristow to move the Tax Revenue Supervisors and relinquishing immunity in the Whiskey Ring cases, which made Grant a protector of political patronage. In fairness, Grant did appoint cabinet reformers and special prosecutors who were able to clean up the Treasury, Interior, War, and Justice departments. Grant, himself, personally participated in reforming the Department of Indian Affairs, by firing all the corrupt clerks. No reforming cabinet member, however, was installed in the Department of Navy.[35]

Grant's scandals ultimately undermined his presidential achievements. These include his support for and protection of African Americans, stabilizing the nation after the turbulent American Civil War, professionalizing the Civil Service, and advocating the humane treatment of Native Americans.[5]

See also

References

- ^ Hinsdale (1911), pp.207, 212–213

- ^ Hinsdale 1911, pp.211–212

- ^ #McFeely-Woodward (1974), pp. 133–134

- ^ Cengage Advantage Books: Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People (2012), p. 593

- ^ a b "Daugherty (April 24, 2020)".

- ^ Kiersey 1992

- ^ a b c d e Woodward 1957

- ^ a b Grant (1885–1886). Chapter II.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Chernow 2017, p. 648.

- ^ "Ulysses S. Grant, Jr". Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Williams (1895). Occasional Addresses Gen. U.S. Grant. p. 8.

- ^ Nevins (1957), Hamilton Fish: The Inner History of the Grant Administration. Volume: 2, pages 719, 720, 727

- ^ a b Ackerman (2011), The Gold Ring, p. 60

- ^ a b Ackerman (2011), The Gold Ring p. 84

- ^ Ackerman (2011), The Gold Ring, p. 91

- ^ a b c Smith 2001, pp.481–490

- ^ Hesseltine (1935), Ulysses S. Grant: Politician, pp 171–175

- ^ McFeely (2002), Grant: A Biography, pp 321–325

- ^ Bunting III 2001, pp.96–98

- ^ McFeely 1981, p.414

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp.328–329

- ^ "The New York Custom House". New York Times. August 5, 1872.

- ^ a b Grossman (2002), Political Corruption in America: an encyclopedia of scandals, power, and greed, pp. 308–309

- ^ a b R., F.D. (October 17, 1881). "Star Routes in the Past". New York Times.

- ^ O'Brien 1918, p.307

- ^ Smith 2001, p.553

- ^ Chernow 2017, p.754

- ^ Hinsdale 1911, pp.212–213

- ^ McFeely 1981, p.397

- ^ a b c Spencer (1913), pp. 452–453.

- ^ a b McFeely-Woodward (1974) pp. 147–148.

- ^ Smith 2001, p.578

- ^ a b Salinger 2005, pp.374–375

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp.430–431

- ^ a b Pierson 1880, pp.343–345

- ^ McFeely 1981, p.391

- ^ a b Smith 2001, p. 584

- ^ a b c Shenkman 2005 History News Network

- ^ a b c d e f Rives 2000

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 405–406

- ^ a b Stevens 1916, pp.109–130

- ^ a b Bunting III 2001, pp.136–138

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 409

- ^ a b Rhodes 1912, p. 187

- ^ a b Grossman 2003, pp. 182–183

- ^ McFeely (2002), Grant, p. 409

- ^ Charles Calhoun, "The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant, 520

- ^ Charles Calhoun, "The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant", 521

- ^ a b McFeely 2002, p.415

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 590,593

- ^ Garland 1898, p. 440

- ^ Harper's Weekly Archive 1876

- ^ Donovan (2008), p. 104.

- ^ a b Barnett 2006, pp.256–257

- ^ a b Smith 2001, pp. 593–596

- ^ Donovan (2008), pp. 106, 107.

- ^ Bunting III 2004, pp.135–136

- ^ a b c Simon 2005, pp.62–63

- ^ a b c Swann 1980, pp.125–135

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 432

- ^ Safe Burglary Case 9/8/1876

- ^ Safe Burglary Case 9/23/1876

- ^ Pesca 2005

- ^ Cozzens, Peter. "Grant's Uncivil War". Smithsonian. November 2016.

- ^ a b c "Fact check: Have presidents before Donald Trump appointed family members to White House positions?". ballotpedia.org. January 17, 2017. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 585.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 597.

- ^ ""Boss" Tweed delivered to authorities". history.com. November 19, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 484, 490, 548, 585, 597.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 739–740.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 739–741, 751–752.

- ^ Twain 1874

- ^ Calhoun 2007, pp.1–2

- ^ a b Nevins (1957) Hamilton Fish: The Inner History of the Grant Administration Vol. 2, pp 638–639

- ^ Bunting III 2004, p.ii

Bibliography

Books

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (2001). Nothing Like it in the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad, 1863–1869. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84609-8.

- Barnett, Louise (2006). Touched by fire: the life, death, and mythic afterlife of George Armstrong. Bison Books. ISBN 978-0-8032-6266-9.

- Bunting III, Josiah (2001). A. M. Schlesinger Junior (ed.). Ulysses S. Grant. Times Books, Henry Holt and Company, LCC. ISBN 0-8050-6949-6.

- Calhoun, Charles William (2007). The gilded age: perspectives on the origins of modern America. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5038-4.

- Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-487-6.

- Donovan, James (2008). A Terrible Glory. New York, New York: Back Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-316-15578-6.

- The Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 8. New York: J.B. Lyon Company. 1918.

- Garland, Hamlin (1898). Ulysses S. Grant His life and character. New York Doubleday (publisher).

- Grossman, Mark (2003). Political corruption in America: an encyclopedia of scandals, power, and greed. ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-57607-060-4.

- Hatfield, Mark O.; Ritchie, Donald A. (2001). Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789- 1993 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9996439895.

- Hinsdale, Mary Louise (1911). A History of the President's Cabinet. Ann Arbor, MI: G. Wahr.

- McFeely, William S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-32394-3.

- Morris, Charles R. (2005). The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J.P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy. New York: H. Holt and Co. ISBN 0-8050-8134-8.

- O'Brien, Frank Michael (1918). The story of the Sun: New York, 1833–1918. New York: Doran.

- Pierson, Arthur Tappan (1880). Zachariah Chandler: an outline sketch of his life and public services. Detroit: Post and Tribune.

- Rhodes, James Ford (1912). History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the Final Restoration of Home Rule at the South in 1877. New York: The MacMillan Company.

- Salinger, Lawrence M. (2005). Encyclopedia of White-collar & Corporate Crime. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. ISBN 0-7619-3004-3.

- Simon, John Y.; Grant, Ulysses S. (2005). The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. Vol. 27. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-2631-0.

- Slap, Andrew L. (2006). The doom of Reconstruction: the liberal Republicans in the Civil War era. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-2709-9.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2001). Grant. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

- Spenser, Jesse Ames (1913). Edwin Wiley (ed.). The United States Its Beginnings, Progress and Modern Development. Vol. 9. New York, New York: American Educational Alliance.

- Stevens, Walter Barlow; Bixby, William Kenny (1916). Grant in Saint Louis. Franklin Club of Saint Louis.

- Swann, Leonard Alexander (1980). John Roach, maritime entrepreneur. Ayer Co Pub. ISBN 978-0-405-13078-6.

- Twain, Mark; Warner, Charles Dudley (1874). The Gilded Age. Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1-142-68887-5.

Newspapers

- Staff writer (September 8, 1876). "The Safe Burglary Case: Preparing for the trial – Witnesses for the defense summoned". The New York Times. New York, NY.

- Staff writer (September 23, 1876). "The Safe Burglary Case: Columbus Alexander and Major Richards of the Washington police examined". The New York Times. New York, NY.

Online

- "1876 Events". Harpers Weekly. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- Kennedy, Robert C. Kennedy (2001). "'Why We Laugh' Pro Tem". Harper's Weekly. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- Kiersey, David; Choiniere, Ray. "Excerpted from Presidential Temperaments". keirsey.com. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- "Party Divisions of the House of Representatives (1879 to Present)". U.S. House of Representatives. Archived from the original on October 25, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- "Party Division in the Senate, 1789–Present". U.S. Senate. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- Pesca, Mike (November 2, 2005). "Orville Babcock's Indictment and the CIA Leak Case". Day to Day. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- Rives, Timothy (2000). "Grant, Babcock, and the Whiskey Ring". archives.gov. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- Shenkman, Rick. "The Last High White House Official Indicted While in Office: U.S. Grant's Orville Babcock". History News Network. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- Woodward, C. Vann (April 1957). "The Lowest Ebb". American Heritage. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- Daugherty, Greg (April 24, 2020). "President Ulysses S. Grant: Known for Scandals, Overlooked for Achievements". Retrieved August 12, 2024.

External links

- Kelly, Martin. "Top 10 Presidential Scandals". AmericanHistory.about.com. Archived from the original on January 31, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- "Learn About the Gilded Age". Digital History. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008.

- Scaturro, Frank (President of the Grant Monument Association). "The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant".

- "Ulysses S. Grant". UVA Miller Center of Public Affairs. September 26, 2016.

- "Ulysses S. Grant". White House Official Website. December 30, 2014.