Pratapgarh Kingdom

Pratapgarh | |

|---|---|

1489–1700s AD

| |

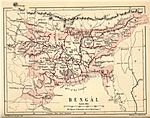

Present-day Karimganj district (blue) and surrounding areas | |

| Capital | Patharkandi |

| Religion | Islam, Hinduism, Tribal Religions |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Raja Sultan | |

• 1489–1490 | Malik Pratap (first) |

• c. 1700s | Aftab Uddin (last) |

| Historical era | Middle Ages |

• Independence from Tripura | 1489 |

• Kachari conquest | 1700s |

| History of Bengal |

|---|

|

The Pratapgarh Kingdom (Bengali: প্রতাপগড় রাজ্য) was a medieval state in the north-east of the Indian subcontinent. Composed of the present-day Indian district of Karimganj, as well as parts of Tripura State and Sylhet, Bangladesh, the kingdom was ruled by a line of Muslim monarchs over a mixed population of Hindu and Islamic adherents. It was bordered by the larger kingdoms of Kachar, Tripura and Bengal.

Centred around the hilly, forested region which forms the modern border between eastern Bangladesh and India, the lands which later formed Pratapgarh were initially under the control of the rulers of Tripura and were principally inhabited by Hindu tribes. It is believed that during the latter years of the 15th century AD, the area was seceded by Malik Pratap, a landowner of mixed native and Persian ancestry, who established the kingdom and from whom it may have received its name. Under the rule of his grandson, Sultan Bazid, the influence of Pratapgarh reached its zenith, developing into a significant cultural centre. It also became a notable military power, defeating the stronger kingdom of Kachar as well as engaging against the dominance of Bengal. It was during this time that the state enjoyed its territorial peak, having briefly captured Sylhet from the latter.

Pratapgarh was eventually captured and dissolved by Kachar during the early 18th century, with its ruling family later only governing as Zamindars under the British. However, the kingdom's legacy continued to have a notable impact in the region, with its name being borne by subsequent administrative divisions in the area and its history and legends surviving as oral traditions among the local population.

Origins

Early history

The heartland of the later Pratapgarh Kingdom, on the present border of southern Sylhet and the Indian state of Tripura, has undergone several name changes in its history. Originally called Sonai Kachanpur, the area was renamed Chatachura after the wandering Magadhan prince Chatra Singh, who received the land as a gift from the Maharaja of Tripura c. 1260 AD, about two hundred years prior to Pratapgarh's foundation.[1][2] Singh's new principality was hilly country, having been located on the south-eastern corner of the Adal-ail and Du-ail ranges.[2][note 1] Incorporating dense, tiger-inhabited forests,[4][5] his territory stretched from Karimganj up to parts of the Lushai Hills and had its capital in Kanakpur, named after his son Kanak Singh. The latter's own son, Pratap Singh, later founded a new town which he named Pratapgarh after himself.[6][note 2] It has been suggested that the Pratapgarh Kingdom, established centuries later, received its name from Pratap Singh and this settlement.[8] Alternatively, the name may have come from the first ruler of the state, the Muslim Malik Pratap.[9]

Pratap Singh appears to have maintained marital relations with contemporary neighbouring kingdoms: his father had previously married a princess of Tripura while his sister Shantipriya married Garuda of Gour, a cousin to Gour Govinda, the last king of Sylhet. The latter couple received a portion of Singh's kingdom as a dowry, which later became known as Chapghat.[10][note 3] Singh's own family may not have left heirs however, as by the 15th century AD, his royal palace was in the hands of Muslim lords.[9]

Founding of the ruling dynasty

The earliest recorded member of the royal family of Pratapgarh was a Persian noble, Mirza Malik Muhammad Turani, who lived at the close of the 14th century AD. Turani, as a result of family feuds in his native Iran, migrated to the Indian subcontinent with a large force, first going to Delhi before settling in present-day Karimganj district.[9][12] Although by this point nearby Sylhet had long since been conquered for Islam by the warrior-saint Shah Jalal, the area to which Turani arrived was in the dominion of the Maharaja of Tripura, still under the control of Hindu tribes.[13]

According to local legend, Turani, after settling into the area, came upon a beautiful woman bathing in a river and immediately fell in love with her. After discovering that the woman, named Umavati, was of noble birth, he went to her father, the local Khasi governor Pura Raja, to ask for her hand in marriage. Reluctant to marry his daughter to a Muslim, Pura Raja rejected the proposal. Turani, humiliated, led his forces in an attack on Pura Raja's fort and captured it, forcing the governor to acquiesce to the marriage. Further to this, as he had no sons, Pura Raja also agreed to name Turani his successor.[14]

According to the researcher Habib Ahmed Duttchowdhury, Turani is identical to the Timurid prince Muhammad Sultan Mirza, grandson of the Central Asian conqueror Timur. He states that the capture of Pura Raja's lands had been during a sojourn in Bengal in the midst of Timur's Indian campaign of 1398, after which Muhammad Sultan with Umavati (converted to Islam under the name Daulat Sultan) returned to Central Asia. Duttchowdhury continues that following Muhammad Sultan's death in 1403, Umavati alias Daulat Sultan went back to her homeland with their young son and took up its rule upon Pura Raja's death.[15]

History

Independence from Tripura

According to historian Achyut Charan Choudhury, Turani's great-great-grandson Malik Pratap was the ruler of the region in the late 15th century AD. By this point, Pratap had gained the former lands and palace of Pratap Singh in Patharkandi by marrying the daughter of the then-current owner, Amir Ajfar.[16]

In 1489, Maharaja Pratap Manikya of Tripura was engaged in a war against his elder brother, Dhanya, after taking the throne with the help of his army generals. While the Maharaja was distracted and lacked the means to intervene, Malik Pratap was said to have seceded Pratapgarh from Tripura's control (an area roughly equivalent to what is now Karimganj district) and declared himself its independent ruler.[17][18] Malik Pratap later aided the Maharaja in his war and earned his friendship through this assistance. In gratitude, Manikya recognised Pratapgarh's independence and awarded Malik Pratap the title of Raja. Further to this, the Maharaja gave his daughter Ratnavati Devi in marriage to Malik Pratap's grandson, Bazid. However, in 1490, Pratap Manikya was assassinated by his generals, with Malik Pratap dying soon afterwards.[19][20]

War against Sultanate of Bengal

After ascending the throne, Bazid repulsed an invasion by the powerful neighbouring kingdom of the Kachari of Maibong. In light of this achievement, he took the new title of Sultan, placing himself on the same level as the Sultan of Bengal.[21] His capital became associated with outposts and forts and developed into an important trade centre,[22] with the floral stonework produced in the region being considered noteworthy.[17]

It was during this zenith of Bazid's power that Gouhar Khan, the Bengali governor of Sylhet, died. Khan's assistants, Subid Ram and Ramdas, took advantage of his death and embezzled a large amount of money from the state government. Then, fearing the wrath of the Sultan of Bengal, Alauddin Husain Shah, they fled to Pratapgarh.[23] Bazid gave his protection to the two fugitives and, seeing the disunity in Sylhet, also seized control of the district and added it to his own domain.[24]

Hussain Shah, wishing to avoid war, sent one of his nobles, a recently converted Muslim from Sylhet named Surwar Khan, to negotiate with the Sultan of Pratapgarh.[23][25] Surwar Khan was unsuccessful in this and was forced to face Bazid in battle, with the latter's forces being bolstered by his allies Shri Shikdar and Islam Roy (the zamindars of Ita and Kanihati respectively), as well as the zamindar of Jangalbari. Though the rebels reportedly fought well, with Bazid's son Marhamat Khan in particular fighting with distinction, they were eventually defeated.[26][27]

Hussain Shah agreed to allow Bazid to continue as ruler of Pratapgarh with relative independence, but he was required to surrender his control of Sylhet and give up the title of Sultan. A tribute of money and elephants was given to show Bazid's loyalty and the two fugitives, Subid Ram and Ramdas, were sent to Hussain Shah to face punishment. Finally, Surwar Khan was named the new governor of Sylhet, with Bazid's daughter Lavanyavati being given in marriage to Surwar's son and eventual successor, Mir Khan.[23][27] The elderly Bazid died soon after the defeat.[23]

The dating of this event, as well as that of the reign of Bazid himself, has been a matter of dispute among academics. Choudhury, who sourced the above account, has the sultan who Bazid angered be Alauddin Husain Shah, whose reign began at the end of the 15th century AD.[23][28] However, Subir Kar, a professor at Assam University, identified the ruler as being the similarly-named Hussain Shah Sharqi of Jaunpur, with the described conflict instead taking place in 1464 AD.[24] This dating is mirrored by Basil Copleston Allen, an Indian Civil Service commissioner, in his Assam District Gazetteers.[29] Alternatively, Syed Murtaza Ali placed the lifetimes of both Malik Pratap and Bazid as being over a century later, with the latter ruler instead being a contemporary of the Mughal emperor Jahangir. Ali suggests that Bazid was identical to Bayazid of Sylhet, who was not subjugated by a reigning monarch, but rather by the Mughal governor of Bengal, Islam Khan I, in 1612 AD.[30]

Kachari invasion

By the early 18th century AD, Aftab Uddin, the grandson of Marhamat Khan and great-grandson of Bazid, was the Raja of Pratapgarh. During this time, he entered a dispute with the king of Kachar.[23] It escalated to the point where Kachar launched an invasion, the second in Pratapgarh's history, led by the Kachari king himself. Aftab Uddin and his soldiers met the invading army before it had entered too far into his territory and in the ensuing battle, the Kachari king was killed.[23][note 4]

The Kachari queen, Kamala of Jaintia, was angered by her husband's death and led a second, much larger army against Pratapgarh. Aftab Uddin's weaker forces were defeated, with the Raja himself and many of his brothers being killed; one historian described the defeated army as being like "floating grass in the face of a flood." Kamala then had the royal palace in Patharkandi looted in revenge. The surviving members of the royal family were forced to flee to their relatives in Jangalbari, located in modern-day Kishoreganj,[note 5] while Pratapgarh was incorporated into the Kachari Kingdom.[33]

Zamindars of Pratapgarh

The Kachari Kingdom lacked the administrative capabilities to maintain a permanent military presence in Pratapgarh. Within a few years, the state reverted to being a part of Tripura, as it had been centuries earlier. Relatives of Aftab Uddin then returned from Jangalbari to regain control of their ancestral land. The head of the former royal family at this point was a nephew of the old Raja, Sultan Muhammad, who was nicknamed "Ranga Thakur" (the Scarlet Lord) and was famous for his physical beauty. However, he did not have the abilities to once again make Pratapgarh an independent kingdom and remained a mere Zamindar under the overlordship of the Maharaja of Tripura.[34][35]

His powers were further diminished when he quarrelled with his cousin Ajfar Muhammad who, though being younger, believed that he should have inherited the land. Ajfar Muhammad rebelled and seceded the northern part of Pratapgarh, establishing a separate Zamindari which he named Jafargarh.[34] When he died without issue, Sultan Muhammad's brother Siraj Uddin Muhammad inherited Jafargarh, with his descendants later becoming very powerful Zamindars in their own right; this clan later subdivided into the five thakur families of Atanagar, Alinagar, Shamshernagar, Rasulnagar and Achalnagar.[36]

Sultan Muhammad's own descendants (who later adopted the title Choudhury) lost further lands in the following centuries, most notably in the lead up to the Revolt of Radharam in 1786 AD.[37][38] Their territories were incorporated by the East India Company around this time, under whom they were landlords through Permanent Settlement.[39] They continued being prominent landowners into the 20th century.[40]

Other members of the erstwhile royal dynasty are believed to have gone east and joined the nobility of the Kingdom of Manipur. This group was descended from the family of Muhammad Sani (himself of the line of Muhammad Turani), who became one of the ministers of King Khagemba. They later formed the Tampakmayum, Touthongmayum and Khullakpam clans of Manipur.[41]

Peoples and customs

The greater Barak Valley, which encompassed the area of Pratapgarh,[42] has an indigenous population of ethnic Bengalis.[43] As with neighbouring Sylhet, the inhabitants speak a common dialect of Bengali known as Sylheti, with the region as a whole, in the words of historian Jayanta Bhattacharjee, being "geographically, historically and ethnically an extension of Gangetic Bengal".[44]

The lands which made up Pratapgarh itself, since long before its founding, have exhibited a strong tribal influence. The Kuki people had been established in the area since at least the mid-1200s AD, when they were the primary population group, and uninterruptedly resided in the region up to the present-day.[2][45] The Khasi people have also maintained a presence and though Pura Raja had been their last important chief,[46] the chronicler Mirza Nathan notes in his Baharistan-i-Ghaibi that even in the 17th century AD, they enjoyed an essentially independent status in the kingdom.[47][note 6] Nathan also records that the territory was further inhabited by the "Mughols" (likely referring to the Manipuris). He describes them as speaking a language "akin to the language of the Kacharies" and wearing "big turbans" and "big ear rings of brass called tunkal".[49]

While such Hindu tribal groups had long held sway in the region, Islam too was deep rooted among the populace. Following his conquest of Sylhet, Shah Jalal was said to have dispatched one Shahid Hamja, who had been among his 360 disciples, to the area to propagate the faith. This saint was attributed with possessing the supernatural ability to control wild animals, leading to the common depiction of him having rode a tiger as a steed. Over the centuries, a popular cult formed around this figure, who was later deified, with his name being corrupted to "Sahija Badsah", thus becoming the presiding god of the forest of Pratapgarh.[note 7] His maqam, which is located there, is venerated by timber merchants, Hindu and Muslim alike, with the lower-caste Hindus of Karimganj district as a whole also paying homage to him.[51][52]

Legacy

Years after the kingdom's dissolution, the name "Pratapgarh" survived as designations for the successive administrative regions which subsequently occupied the area. Over a number of centuries, various mahals, tehsils, mouzas and paraganas with this name were maintained by the Mughal and British empires, as well as later by the Republic of India.[53][54][7][55] Pratapgarh also had a notable impact on the culture of the region. Choudhury records various legends and anecdotes from the kingdom's history which were still in vogue among the population of the area. Archaeological remnants, which include dighi (reservoirs), graves and the ruins of the capital, further appear to have impacted the popular consciousness. A song regarding the remains of the royal palace was reported by Choudhury as having been popular among the local villages:[56]

মন চল যাইরে, প্রতাপগড়ের রাজবাড়ী দেখি আই রে।

পানিত কান্দে পাণি খাউরি শুকনায় কান্দে ভেউী।

কাঁটাব জঙ্গল লাগিয়া রইছে আজফরের বাড়ী-মন চল যাইরে।

Come oh brother, let us go see the palace of Pratapgarh.

Weep in rain, weep in the dry,

for Ajfar's home will disappear in the jungle thorns.

Genealogy of the Rajas of Pratapgarh

| Family tree[57] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ^ These hills are also known as the Patharia and Pratapgarh ranges respectively.[3]

- ^ The garh suffix roughly translates to "fort".[7]

- ^ Both Shantipriya and Garuda committed suicide in the aftermath of the Conquest of Sylhet in 1303 AD.[11]

- ^ There is some dispute about the identity of this king, who is unnamed in local histories. Choudhury believes that this ruler was Tulsidhaja, who reigned after 1730 AD.[23][31] Alternatively, Upendra Guha suggests that it was Tamradhaja, who ruled a generation earlier, placing these events around 1708.[32]

- ^ Aftab Uddin's paternal grandmother, the wife of Marhamat Khan, had been a daughter of a former lord of Jangalbari.[19]

- ^ This group associated Pura Raja with a number of local legends where he is linked with the worship of fishing goddesses and ceremonial large-scale fishing, a religious festival which continued into modern times.[48][46]

- ^ The title badsah may have been applied to Hamja by the local population because of his temporal and political authority over the region.[50]

- ^ A grandson of Syed Khudawand, ruler of Taraf.[58]

- ^ A relative of Syed Qalandar.[58]

References

- ^ Choudhury (2000), p. 303.

- ^ a b c Nath (1948), p. 81.

- ^ Das (2008), p. 17.

- ^ Abbasi & Al Helal (1979), p. 65.

- ^ Clothey (1982), p. 126.

- ^ Nath (1948), pp. 81, 119.

- ^ a b Bhattacharjee (1982), p. 2.

- ^ Allen (2013), p. 62.

- ^ a b c Choudhury (2000), p. 304.

- ^ Nath (1948), p. 119.

- ^ Nath (1948), p. 122.

- ^ Nazir (2013), p. 92.

- ^ Choudhury (1980), p. 237.

- ^ Choudhury (2000), p. 305.

- ^ Duttchowdhury (2024), pp. 80–86.

- ^ Choudhury (2000), pp. 304–05.

- ^ a b Choudhury (2000), p. 306.

- ^ Chaudhury (1979), p. XI.

- ^ a b Choudhury (2000), p. 307.

- ^ Durlabhendra, Sukheshwar & Baneshwar (1999), p. 60.

- ^ Choudhury (2000), p. 308.

- ^ Sinha, Chacko & Aier (1993), p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Choudhury (2000), p. 310.

- ^ a b Kar (2008), p. 135.

- ^ Bhattacharjee (1994), p. 74.

- ^ Choudhury (2000), pp. 214, 310.

- ^ a b Motahar (1999), p. 715.

- ^ Tarafdar (1999), p. 376.

- ^ Allen (2013), p. 94.

- ^ Ali (1965), p. 69.

- ^ Guha (1971), p. 81.

- ^ Guha (1971), p. 73.

- ^ Choudhury (2000), p. 311.

- ^ a b Choudhury (2000), p. 312.

- ^ Chaudhury (1979), p. XIV.

- ^ Choudhury (2000), p. 312–13.

- ^ Choudhury (2000), p. 313-16.

- ^ Bhattacharjee (2005), pp. 176–77.

- ^ Bhattacharjee (2005), p. 177.

- ^ Choudhury (2000), p. 321.

- ^ Nazir (2013), pp. 90–92.

- ^ Bhattacharjee (1994), p. 66.

- ^ Bhattacharjee (1994), p. 63.

- ^ Bhattacharjee (1986), p. 81.

- ^ Agrawal & Kumar (2020), p. 310.

- ^ a b Choudhury (1996), p. 37.

- ^ Nathan (1936), p. 324.

- ^ Choudhury (1980), p. 235.

- ^ Sanajaoba (1988), p. 120.

- ^ Choudhury (1977), p. 62.

- ^ Abbasi & Al Helal (1979), p. 64.

- ^ Choudhury (1977), pp. 62–63.

- ^ Bhattacharjee (1991), p. 126.

- ^ Mali (1985), p. 169.

- ^ Mittal (1984), p. 73.

- ^ Choudhury (2000), pp. 304–11.

- ^ Choudhury (2000), pp. 304–313, 529.

- ^ a b c d Choudhury (2006), p. 342.

Bibliography

- Abbasi, Mustafa Zaman; Al Helal, Bashir (1979), Folkloric Bangladesh, Dhaka: Bangladesh Folklore Parishad

- Agrawal, Ankush; Kumar, Vikas (2020), Numbers in India's Periphery: Political Economy of Government Statistics: The Political Economy of Government Statistics, India: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-108-48672-9

- Ali, Syed Murtaza (1965), হযরত শাহ জালাল ও সিলেটের ইতিহাস (in Bengali), Dhaka: বাঙলা একাডেমী

- Allen, Basil Copleston (2013) [1905], Assam District Gazetteers, vol. 2 (2nd ed.), Guwahati: Narayani Handiqui Historical Institute, ISBN 9780343330132

- Bhattacharjee, J.B. (1982), "Mirza Nathan's Kachar", Social Research, 2 (3), Shillong: Pub. Division

- Bhattacharjee, J.B. (1994), Milton S. Sangma (ed.), "The Pre-Colonial Political Structure of Barak Valley", Essays on North-east India: Presented in Memory of Professor V. Venkata Rao, New Delhi: Indus Publishing, ISBN 978-81-7387-015-6

- Bhattacharjee, J.B. (2005), "Revolt of Nawab Radharam (1786)" (PDF), Proceedings of North East India History Association, 26, Guwahati: Gauhati University, archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2021, retrieved 10 July 2020

- Bhattacharjee, Jayanta Bhusan (1986), H. K. Barpujari (ed.), "Glimpses of the Pre-Colonial History of Cachar", Studies in the History of North-East India: Essays in Honour of Professor H.K. Barpujari, Shillong: North Eastern Hill University Publications

- Bhattacharjee, Jayanta Bhusan (1991), Social and polity formations in pre-colonial north-east India: the Barak Valley experience, New Delhi: Har-Anand Publications in association with Vikas Pub. House, ISBN 9780706954647

- Chaudhury, A.K. Dutta (1979), Some aspects of socioeconomic conditions of Karimganj since independence with special reference to community development (PDF), Gauhati: Gauhati University

- Choudhury, Achyut Charan (2000) [1910], Srihatter Itibritta: Purbangsho (in Bengali), Kolkata: Basanti Press

- Choudhury, Achyut Charan (2006) [1917], Srihatter Itibritta: Uttarrangsho (in Bengali), Kolkata: Basanti Press

- Choudhury, Sujit (1977), A study of the folkcults of the Bengalee Hindus of Cachar district (PDF), Gauhati: Gauhati University

- Choudhury, Sujit (1980), "The origin and development of Kapilashram of Gangasagar and Siddheswar– an outline of comparative study", Folk-lore, 21 (10), Indian Publications

- Choudhury, Sujit (1996), Folklore and History: A Study of the Hindu Folkcults of the Barak Valley of Northeast India, Delhi: K.K. Publishers

- Clothey, Fred W. (1982), Images of Man: Religion and Historical Process in South Asia, Madras: New Era Publications

- Das, Partha Sarathi (2008), Herbaceous flora of Karimganj district Assam with reference to their economic utility (PDF), vol. I, Silchar: Assam University

- Durlabhendra; Sukheshwar; Baneshwar (1999), Sri Rajmala, translated by Kailāsa Candra Siṃha; N.C. Nath, Agartala: Tribal Research Institute, Govt. of Tripura

- Duttchowdhury, Habib Ahmed (2024), ভারতবর্ষের ইতিহাসে শ্রীহট্টের প্রতাপগড় রাজ্য (in Bengali), Dhaka: মোস্তফা সেলিম উৎস প্রকাশন, ISBN 978-984-97871-7-4

- Guha, Upendra Chandra (1971), কাছাড়ের ইতিবৃত্ত (in Bengali), Guwahati: আসম প্রকাশন পরিষদ

- Kar, Subira (2008), 1857 in North East: a reconstruction from folk and oral sources, New Delhi: Akansha Publishing House, ISBN 978-81-8370-131-0

- Mali, Dharani Dhar (1985), Revenue Administration in Assam, New Delhi: Omsons Publications

- Mittal, K.M. (1984), Report on the Administration of North East India, Delhi: Mittal Publications

- Motahar, Hosne Ara (1999), Sharif Uddin Ahmed (ed.), "Museum Establishment and Heritage Preservation: Sylhet Perspective", Sylhet: History and Heritage, Sylhet: Bangladesh Itihas Samiti, ISBN 978-984-31-0478-6

- Nath, Rajmohan (1948), The back-ground of Assamese culture, Nongthymmai: A. K. Nath

- Nathan, Mirza (1936), Bahāristān-i-Ghaybī: A History of the Mughal Wars in Assam, Cooch Behar, Bengal, Bihar and Orissa During the Reigns of Jahāngīr and Shāhjahān, vol. I, translated by M.I. Borah, Government of Assam, Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies, Narayani Handiqui Historical Institute

- Nazir, Ahamad (2013), "The Muslims in Manipur: A study in their History and Culture", INFLIBNET, Imphal: Manipur University, hdl:10603/39985

- Sanajaoba, Naorem (1988), Manipur, Past and Present: The Heritage and Ordeals of a Civilization, vol. 4, New Delhi: Mittal Publications, ISBN 978-81-7099-853-2

- Sinha, Awadhesh Coomar; Chacko, Pariyaram Mathew; Aier, I. L. (1993), Hill cities of eastern Himalayas: ethnicity, land relations and urbanisation, New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company, ISBN 978-81-85182-80-3

- Tarafdar, Momtazur Rahman (1999), Husain Shahi Bengal, 1494–1538 A.D.: A Socio-political Study, Dhaka: University of Dhaka