Potter wasp

| Potter wasp | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ancistrocerus species[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Vespidae |

| Subfamily: | Eumeninae |

| Diversity | |

| Almost 200 genera and 3000 species | |

Potter wasps (or mason wasps), the Eumeninae, are a cosmopolitan wasp group presently considered a subfamily of Vespidae, but sometimes recognized in the past as a separate family, Eumenidae.

Mud dauber wasps, which also build their nests with mud, are in the families Sphecidae and Crabronidae and not discussed here.

Recognition

Most eumenine species are black or brown, and commonly marked with strikingly contrasting patterns of yellow, white, orange, or red (or combinations thereof), but some species, mostly from tropical regions, show faint to strong blue or green metallic highlights in the background colors. Like most vespids, their wings are folded longitudinally at rest. They are particularly recognized by the following combination of characteristics:

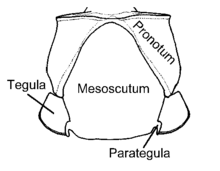

- a posterolateral projection known as a parategula on both sides of the mesoscutum;

- tarsal claws cleft;

- hind coxae with a longitudinal dorsal carina or folding, often developed into a lobe or tooth, and;

- fore wings with three submarginal cell.

Biology

Eumenine wasps are diverse in nest building. The different species may either use existing cavities (such as beetle tunnels in wood, abandoned nests of other Hymenoptera, or even man-made holes like old nail holes and screw shafts on electronic devices) that they modify in several degrees, or they construct their own either underground or exposed nests. The nest may have one or several individual brood cells. The most widely used building material is mud made of a mixture of soil and regurgitated water, but many species instead use chewed plant material.

The name "potter wasp" derives from the shape of the mud nests built by species of Eumenes and similar genera. It is believed that Native Americans based their pottery designs upon the form of local potter wasp nests.[2] The female wasp scrapes up mud or dirt with her mandibles and front legs, combining it with water and saliva to form a mud ball she transports back to adds to her nest under construction.

All known eumenine species are predators, most of them solitary mass provisioners, though some isolated species show primitive states of social behaviour and progressive provisioning.

When a cell is completed, the adult wasp typically collects beetle larvae, spiders, or caterpillars and, paralyzing them, places them in the cell to serve as food for a single wasp larva. For example, Euodynerus foraminatus paralyzes the larvae of the poison hemlock moth (A. alstroemeriana).[3] As a normal rule, the adult wasp lays a single egg in the empty cell before provisioning it. Some species lay the egg in the opening of the cell, suspended from a thread of dried fluid. When the wasp larva hatches, it drops and starts to feed upon the supplied prey for a few weeks before pupating. The complete lifecycle may last from a few weeks to more than a year from the egg until the adult emerges. Adult potter wasps feed on floral nectar.

Taxonomy

Potter wasps are the most diverse subfamily of vespids, with almost 200 genera, and contain the vast majority of species in the family (nearly 3,000 species from a total of about 4,500 in the whole family). The overwhelming morphological diversity of the potter wasp species is reflected in the proliferation of genera described to group them into more manageable groups. The subfamily Zethinae was formerly included here, but was removed when it was recognized that it rendered Eumeninae paraphyletic.[4]

Gallery

- Potter wasp nests, Springdale, AR

- Pseudodynerus quadrisectus nest built in a hole bored by a carpenter bee

- Phimenes flavopictus nectaring

- Phimenes flavopictus building nest

- Four-toothed mason wasps in the genus Monobia nectaring on Canadian thistle

References

- ^ Cirrus Digital: Potter Wasp and Mud Pot Nest

- ^ von Frisch, Karl (1974). Animal Architecture. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 55. ISBN 9780151072514.

- ^ McKenna, D.D.; Zangerl, A.R.; Berenbaum, M.R. (2001). "A native Hymenopteran predator of Agonopterix alstroemeriana (Lepidoptera: Oecophoridae) in east-central Illinois". Great Lakes Entomologist. 34. Michigan Entomological Society: 71–75 – via CAB Direct.

- ^ PK Piekarski, JM Carpenter, AR Lemmon, E Moriarty-Lemmon, BJ Sharanowski (2018) Phylogenomic Evidence Overturns Current Conceptions of Social Evolution in Wasps (Vespidae). Molecular Biology and Evolution. doi:10.1093/molbev/msy124

- James M. Carpenter (1986). "A synonymic generic checklist of the Eumeninae (Hymenoptera: Vespidae)". Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 93 (1–2): 61–90. doi:10.1155/1986/12489.

- Carpenter, J. M. & B. R. Garcete-Barrett. 2003. A key to the neotropical genera of Eumeninae (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Boletín del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural del Paraguay 14: 52–73.

- Giordani Soika, 1989. Terzo contributo alla conoscenza degli eumenidi afrotropicali (Hymenoptera). Societa Veneziana di Scienze Naturali Lavori 14(1) 1989: 19–68.

- Giordani Soika, A. 1992. Di alcuni eumenidi nuovi o poco noti (Hymenoptera Vespoidea). Societá Veneziana di Scienze Naturali Lavori 17 1992: 41–68.

- Giordani Soika, A. 1993. Di alcuni nuovi eumenidi della regione orientale (Hym. Vespoidea). Bollettino del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Venezia 42, 30 giugno 1991(1993): 151–163.

- Gusenleitner. 1992. Zwei neue Eumeniden-Gattungen und -Arten aus Madagaskar (Vespoidea, Hymenoptera). Linzer Biologische Beiträge 24(1) 1992: 91–96.

- CSIRO Entomology Division. 1991. The Insects of Australia: a textbook for Students and Research. 2nd Edition. Melbourne University Press and Cornell University Press. 1137 pp.

- Saussure, Henri de. 1852. Monographie des guêpes solitaires ou de la tribu des Euméniens. Genève, J. Cherbuliez, Paris, V. Masson.