Portal:France/Featured Article Archive/2006

| Featured Article Archives | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 Archive | 2006 Archive | 2007 Archive | 2008 Archive | 2011 Archive | 2012 Archive |

| Portal:France/Featured article/Layout | |||||

- January 2006

Joan of Arc, also Jeanne d'Arc (1412 – 30 May 1431), is a national heroine of France and a Saint of the Roman Catholic Church. Many believed she had visions from God that told her to recover her homeland. Early in 1429 she convinced the uncrowned king Charles VII to give her a suit of armor and the permission to relieve the siege at Orléans. Initially treated as a figurehead by veteran commanders, she gained prominence when she lifted the siege in only nine days. After several other engagements and an important victory at Patay she led a bloodless expedition to Reims for Charles VII's coronation. This settled the disputed royal succession and recovered important territory. The renewed French confidence outlasted her own brief career. Wounded at an unsuccessful attempt to recover Paris, she participated in minor actions until her capture outside Compiègne the following spring.

Her Burgundian captors delivered her to the English; who selected clergymen to convict her of heresy. John, Duke of Bedford had her burnt at the stake in Rouen. She had been the heroine of her country at the age of seventeen. She died at just nineteen.

Some twenty-four years later Pope Callixtus III reopened the case. The new finding overturned the original conviction. Her piety to the end impressed the retrial court. Pope Benedict XV canonized her on 16 May 1920.

Joan of Arc has remained an important figure in the collective imagination of Western culture. From Napoleon to the present, French politicians of all leanings have invoked her memory. Major writers and composers who created works about her include Shakespeare, Voltaire, Schiller, Verdi, Tchaikovski, Twain, Shaw, and Brecht. Depictions of her continue in film, in television, and in song. Read more...

- February 2006

Still life with Brioche, Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin, 1763. French cuisine is characterized by its extreme diversity. French cuisine is considered to be one of the world's most refined and elegant styles of cooking, and is renowned for both its classical ("haute cuisine") and provincial styles. Many of the world's greatest chefs, such as Taillevent, La Varenne, Carême, Escoffier, or Bocuse were masters of French cuisine. Additionally, French cooking techniques have been a major influence on virtually all Western cuisines, and almost all culinary schools use French cuisine as the basis for all other forms of Western cooking.

Traditionally, each region of France have their own distinctive cuisine:

- Cuisine from northwest France uses butter, cream (crème fraîche), and apples;

- Cuisine from southwest France uses duck fat, foie gras, porcini mushrooms (cèpes), and gizzards;

- Cuisine from southeast France uses olive oil, herbs, and tomatoes, and shows Italian cuisine influences.

- Cuisine from northern France uses potatoes, porks, endive and beer, and shows Flemish cuisine influences.

- Cuisine from eastern France uses lard, sausages, beer, and sauerkraut, and shows German cuisine influences.

Besides these five general areas, there are many more local cuisines, such as Loire Valley cuisine (famous for its delicate dishes of freshwater fish and Loire Valley white wines), Basque cuisine (famous for its use of tomatoes and chili) and the cuisine of Roussillon, which is similar to Catalan cuisine. With the movements of population of contemporary life, such regional differences are less noticeable than they used to be, but they are still clearly marked, and one travelling across France will notice significant changes in the ways of cooking and the dishes served. Moreover, recent focus of French consumers on local, countryside food products (produits du terroir) means that the regional cuisines are experiencing a strong revival in the early 21st century, especially as the slow food movement is gaining popularity. Read more...

- March 2006

The Algerian War of Independence (1954–62) was a period of guerrilla strikes, maquis fighting, terrorism against civilians on both sides, and riots between the French army and colonists, or the "colons" as they were called, in Algeria and the FLN (Front de Libération Nationale) and other pro-independence Algerians. The struggle was touched off by the FLN in 1954, only two years before France gave up its control over Tunisia and Morocco. The FLN's main Algerian rival — with the same goal of Algerian independence — was the later National Algerian Movement (Mouvement National Algérien, MNA) whose main supporters were Algerian workers in France. The FLN and MNA fought against each other in France and Algeria for nearly the full duration of the conflict.

In the early morning hours of November 1, 1954, FLN maquisards (guerrillas) launched attacks in various parts of Algeria against military installations, police posts, warehouses, communications facilities, and public utilities. From Cairo, the FLN broadcast a proclamation calling on Muslims in Algeria to join in a national struggle for the "restoration of the Algerian state, sovereign, democratic, and social, within the framework of the principles of Islam." The French minister of interior, socialist François Mitterrand, responded sharply that "the only possible negotiation is war." It was the reaction of Premier Pierre Mendès-France, who only a few months before had completed the liquidation of France's empire in Indochina, that set the tone of French policy for the next five years. On November 12, he declared in the National Assembly: "One does not compromise when it comes to defending the internal peace of the nation, the unity and integrity of the Republic. The Algerian departments are part of the French Republic. They have been French for a long time, and they are irrevocably French… Between them and metropolitan France there can be no conceivable secession." Read more...

- April 2006

Henry IV at the Battle of Ivry, by Peter Paul Rubens. The military history of France represents a massive panorama of conflicts and struggles extending for more than 2,000 years over areas encompassing modern France, Europe, and European territorial possessions overseas. Because of such lengthy periods of warfare, the peoples of France have often been at the forefront of military development, and as a result, military trends emerging in France have had a decisive impact on European and world history.

Gallo-Roman conflict predominated from 400 BCE to 50 BCE, with the Romans emerging victorious in the conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar. After the decline of the Roman Empire, a Germanic tribe known as the Franks took control of Gaul by defeating competing tribes. The "land of Francia", from which France gets its name, had high points of expansion under kings Clovis I and Charlemagne. In the Middle Ages, rivalries with England and the Holy Roman Empire prompted major conflicts such as the Hundred Years War. With an increasingly centralized monarchy and the first standing army since Roman times, France came out of the Middle Ages as the most powerful nation in Europe, only to lose that status to Spain following defeat in the Italian Wars. The Wars of Religion crippled France in the late sixteenth century, but a major victory over Spain in the Thirty Years War, with help from Sweden, made France the most powerful nation on the continent once more. The wars of Louis XIV in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries left France territorially larger, but bankrupt.

In the eighteenth century, global competition with Great Britain led to defeat in the French and Indian War, where France lost its North American holdings and India, but consolation came in the form of the American Revolutionary War, where massive French aid led to America's independence.[1] Internal political upheaval eventually lead to 23 years of nearly continuous war in the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars; France reached the zenith of its power during this period, but by 1815 it had been restored to its pre-Revolutionary borders. The rest of the 19th century witnessed the growth of the French colonial empire and wars with Russia, Austria, and Prussia. Following defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, Franco-German rivalry reasserted itself again in World War I, this time France, with British and American aid, emerging as the winner. Tensions over the Versailles Treaty led to the Second World War, where it was humiliated in the Battle of France. The Allies eventually emerged victorious over the Germans, however, and France was given an occupation zone in Germany. The two world wars destroyed Franco-German rivalry and paved the way for European integration, economically, politically, and militarily. Today, French military intervention is most often seen in its former colonies and with its NATO allies in hot spots around the world. Read more...

- May 2006

|:{| Médecins Sans Frontières (ⓘ) is a secular humanitarian-aid non-governmental organisation best known for its projects in war-torn regions and developing countries facing endemic disease.

Médecins Sans Frontières was created in 1971 by a small group of French doctors. The organisation is known to much of the world by its French name or simply as MSF. In many countries (such as the United States), the English-translated name Doctors Without Borders is used instead.

The organisation actively provides health care and medical training to populations in more than 70 countries, and frequently insists on political responsibility in conflict zones such as Chechnya and Kosovo. Only once in its history, during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, has the organisation called for a military intervention.

MSF received the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of its members' continuous effort to provide medical care in acute crises, as well as raising international awareness of potential humanitarian disasters. Dr. James Orbinski, who was the president of the organisation at the time, accepted the prize on behalf of MSF. Read more... |}

- June 2006

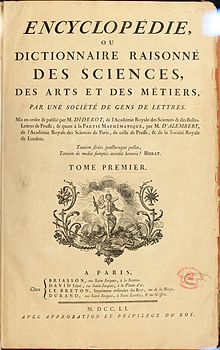

The title page of the Encyclopédie Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (that is, "Encyclopedia, or a systematic dictionary of the sciences, arts, and crafts") was an early encyclopedia, published in France beginning in 1751, the final volumes being released in 1780.

One of the greatest and most remarkable literary enterprises of the 18th century, the famous Encyclopédie originated in a French translation of Ephraim Chambers's Cyclopaedia, begun in 1743 and finished in 1745 by John Mills, an Englishman resident in France, assisted by Gottfried Sellius. Jean Paul de Gua de Malves, professor of philosophy in the College of France, was subsequently engaged as editor merely to correct errors and add new discoveries. But he proposed a thorough revision, and obtained the assistance of many learned men and artists, among were Louis, Condillac, Jean le Rond d'Alembert and Denis Diderot. But the publishers did not think his reputation high enough to ensure success, withheld their confidence, and often opposed his plans as too expensive. Tired at last of disputes and too easily offended, de Gua resigned the editorship. The publishers, who had already made heavy advances, offered the editorship to Diderot, who was probably recommended to them by his very well received Dictionnaire universel de medicine.

The great work comprised 35 volumes, 71,818 articles, and 3,129 illustrations. The first 28 volumes were published between 1751 and 1772 and were edited by Diderot. The remaining 5 volumes were completed by other editors in 1777, along with a 2 volume index in 1780. Many of the most noted figures of the French enlightenment contributed to the work including Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu.

The writers of the encyclopedia saw it as destroying superstitions and providing access to human knowledge. It was a quintessential summary of thought and belief of the Enlightenment. In ancien régime France it caused a storm of controversy, however. This was mostly due to its religious tolerance (though this should not be exaggerated; the article on "Atheism" defended the state's right to persecute and to execute atheists). The encyclopedia praised Protestant thinkers and challenged Catholic dogma. The entire work was banned; but because it had many highly placed supporters, work continued and each volume was delivered clandestinely to subscribers.

It was also a vast compendium of the technologies of the period, describing the traditional craft tools and processes. Much information was taken from the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers. Read more...

- July 2006

The War of the League of Cambrai (1508–16), sometimes known as the War of the Holy League and by several other names, was a major conflict in the Italian Wars. The principal participants of the war were France, the Papal States, and the Republic of Venice; they were joined, at various times, by nearly every significant power in Western Europe, including Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, the Kingdom of England, the Kingdom of Scotland, the Duchy of Milan, Florence, the Duchy of Ferrara, and the Swiss.

Pope Julius II had intended that the war would curb Venetian influence in northern Italy, and had, to this end, created the League of Cambrai (named after Cambrai, where the negotiations took place), an alliance against the Republic that included, besides himself, Louis XII of France, Emperor Maximilian I, and Ferdinand I of Spain. Although the League was initially successful, friction between Julius and Louis caused it to collapse by 1510; Julius then allied himself with Venice against France.

The Veneto-Papal alliance eventually expanded into the Holy League, which drove the French from Italy in 1512; disagreements about the division of the spoils, however, led Venice to abandon the alliance in favor of one with France. Under the leadership of Francis I, who had succeeded Louis to the throne, the French and Venetians would, through their victory at Marignano in 1515, regain the territory they had lost; the treaties of Noyon and Brussels, which ended the war the next year, would essentially return the map of Italy to the status quo of 1508. Read more...

- August 2006

Bernhard of Clairvaux in a medieval illuminated manuscript. The Second Crusade was the second major crusade launched from Europe, called in 1145 in response to the fall of the County of Edessa the previous year. Edessa was the first of the Crusader states to have been founded during the First Crusade (1095–1099), and was the first to fall. The Second Crusade was announced by Pope Eugene III, and was the first of the crusades to be led by European kings, namely Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, with help from a number of other important European nobles.

There had been virtually no popular enthusiasm for the crusade as there had been in 1095 and 1096. However, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, one of the most famous and respected men of Christendom at the time, found it expedient to dwell upon the taking of the cross as a potent means of gaining absolution for sin and attaining grace. On March 31, with Louis present, he preached to an enormous crowd in a field at Vézelay. Bernard, "the honey-tongued teacher" worked his magic of oration, men rose up and yelled "Crosses, give us Crosses!" and they supposedly ran out of cloth to make crosses; to make more Bernard is said to have given his own outer garments to be cut up. Unlike the First Crusade, the new venture attracted Royalty, such as Eleanor of Aquitaine, then Queen of France; Thierry of Alsace, Count of Flanders; Henry, the future Count of Champagne; Louis’ brother Robert I of Dreux; Alphonse I of Toulouse; William de Warenne, 3rd Earl of Surrey; Hugh VII of Lusignan; and numerous other nobles and bishops. But an even greater show of support came from the common people.

The armies of the two kings marched separately across Europe and were somewhat hindered by Byzantine emperor Manuel I Comnenus; after crossing Byzantine territory into Anatolia, both armies were separately defeated by the Seljuk Turks. Louis and Conrad and the remnants of their armies reached Jerusalem and in 1148 participated in an ill-advised attack on Damascus. The crusade in the east was a failure for the crusaders and a great victory for the Muslims. It would ultimately lead to the fall of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade at the end of the 12th century.

The only success came outside of the Mediterranean, where English crusaders, on the way by ship to the Holy Land, fortuitously stopped and helped capture Lisbon in 1147. Meanwhile, in Eastern Europe, the first of the Northern Crusades began with the intent of forcibly converting pagan tribes to Christianity, and these crusades would go on for centuries. Read more...

- September 2006

Asterix (French: Astérix) is a fictional character, created in 1959 as the hero of a series of French comic books by René Goscinny (stories) and Albert Uderzo (illustrations). Uderzo has continued the series since the death of Goscinny in 1977. The 33 main books (one of which is a compendium of short stories) have been translated into more than 100 languages and dialects — some even into Latin, Arabic, Ancient Greek and Esperanto.

The Asterix series is probably the most popular French comic in the world, and familiar to people of all ages in most European countries, Canada, Australia & New Zealand and parts of South America and Asia, particularly Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, India and Indonesia. Asterix is less well known in the United States and Japan.

The key to the success of the series is that it contains comic elements for all ages: young children like the fist-fights and other visual gags, while adults appreciate the cleverness of the allusions and puns that sparkle throughout the texts.

Several books have been made into films, mostly animated, some with live actors. See List of Asterix films and videogames.

Asterix is a small but fearless and cunning warrior, ever eager for any new adventure. He lives around 50 BC in a fictional village in northwest Armorica (a region of ancient Gaul mostly identical to modern Brittany). This village is celebrated as the only part of Gaul not yet conquered by Julius Caesar and his Roman legions. The inhabitants of the village gain superhuman strength by drinking a magic potion prepared by the druid Getafix (French: Panoramix). The village is surrounded by the ocean on one side, and four unlucky Roman garrisons on the other, intended to keep a watchful eye and ensure that the Gauls do not get up to mischief. Read more...

October 2006

A reservoir glass filled with a naturally colored verte next to an absinthe spoon. Absinthe is a distilled, highly alcoholic, anise-flavored spirit derived from herbs including the flowers and leaves of the medicinal plant Artemisia absinthium, also called wormwood. Although it is sometimes incorrectly called a liqueur, absinthe is not bottled with added sugar and is therefore classified as a liquor or spirit.

Absinthe is often referred to as la fée verte (“The Green Fairy”) because of its coloring — typically pale or emerald green, but sometimes clear. Due to its high proof and concentration of oils, absintheurs (absinthe drinkers) typically add three to five parts ice-cold water to a dose of absinthe, which causes the drink to turn cloudy (called “louching”); often the water is used to dissolve added sugar to decrease bitterness. This preparation is considered an important part of the experience of drinking absinthe, so much so that it has become ritualized, complete with special slotted absinthe spoons and other accoutrements. Absinthe’s flavor is similar to anise-flavored liqueurs, with a light bitterness and greater complexity imparted by multiple herbs.

Absinthe originated in Switzerland as an elixir, but is better known for its popularity in late 19th- and early 20th-century France, particularly among Parisian artists and writers whose romantic associations with the drink still linger in popular culture. In its heyday, the most popular brand of absinthe worldwide was Pernod Fils. At the height of this popularity, absinthe was portrayed as a dangerously addictive, psychoactive drug; the chemical thujone was blamed for most of its deleterious effects. By 1915 it was banned in a number of European countries and the United States. Even though it was vilified, no evidence shows it to be any more dangerous than ordinary alcohol although few modern medical studies have been conducted to test this. A modern absinthe revival began in the 1990s, as countries in the European Union began to reauthorize its manufacture and sale. Read more...

November 2006

D-day assault routes into Normandy. The Battle of Normandy was fought in 1944 between Nazi Germany in Western Europe and the invading Allied forces as part of the larger conflict of World War II. Over sixty years later, the Normandy invasion, codenamed Operation Overlord, still remains the largest seaborne invasion in history, involving almost three million troops crossing the English Channel from England to Normandy in then German-occupied France.

The primary Allied formations that saw combat in Normandy came from the United States of America, United Kingdom and Canada. Substantial Free French and Polish forces also participated in the battle after the assault phase, and there were also contingents from Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, the Netherlands, and Norway.

The Normandy invasion began with overnight parachute and glider landings, massive air attacks and naval bombardments, and an early morning amphibious assault on June 6, “D-Day.” The battle for Normandy continued for more than two months, with campaigns to establish, expand, and eventually break out of the Allied beachheads, and concluded with the liberation of Paris and the fall of the Falaise pocket in late August 1944.

The various factions and circuits of the French Resistance (also known as the Maquis) were included in the plan for Overlord. Groups were tasked with attacking railway lines, ambushing roads, or destroying telephone exchanges or electricity sub-stations. They were to be alerted to carry out these tasks by means of the messages personnels, transmitted by the BBC in its French service from London. Several hundreds of these were regularly transmitted, masking the few of them that were really significant. Read more...

December 2006

The Centre Georges Pompidou (constructed 1971–1977 and known as the Pompidou Centre in English) is a building in the Beaubourg area of the IVe arrondissement of Paris, near Les Halles and the Marais. It houses the Bibliothèque publique d'information, a vast public library, and the Musée National d'Art Moderne. Because of its location, the Centre is known locally as Beaubourg. It is named after Georges Pompidou, who was president of France from 1969 to 1974, and was opened on January 31, 1977. Under the guidance of its first director, Pontus Hultén, it quickly became a noted attraction in Paris.

Designed by Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers, Sue Rogers, Edmund Happold, Kristin Mills and Peter Rice, the building structure is very distinctive: it has been described by critics as "an oil refinery in the centre of the city." In the beginning, it was highly controversial; however, its unique appearance has become more accepted. The colored external piping is the special feature of the building. Air conditioning ducts are green; water pipes are blue; and electricity lines are yellow. Escalators and elevators are red. White ducts are ventilation shafts for the underground areas. Even the steel beams that make up the Pompidou Centre's framework are on the outside.

The intention of the architects was to place the various service elements (electricity, water etc.) outside of the building's framework and therefore turn the building "inside out." The arrangement also allows an uncluttered internal space for the display of art works, drawing on ideas promulgated by Cedric Price's Fun Palace project (1964). Read more...