Plan XVII

| Plan XVII | |

|---|---|

| Part of First World War | |

| |

| Operational scope | Strategic |

| Location | Lorraine, northern France and Belgium 48°45′15.84″N 05°51′6.12″E / 48.7544000°N 5.8517000°E |

| Planned | 1912–1914 |

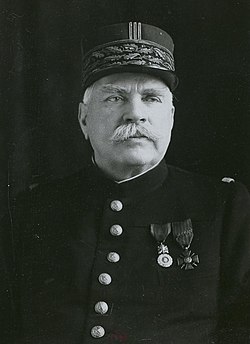

| Planned by | Joseph Joffre and the Conseil Supérieur de la Guerre |

| Commanded by | Joseph Joffre |

| Objective | Decisive defeat of Imperial German Army |

| Date | 7 August 1914 |

| Executed by | French Army |

| Outcome | Failure |

| Casualties | 329,000 |

Grand Est, the modern French administrative region of north-eastern France (including Alsace and Lorraine) | |

Plan XVII (pronounced [plɑ̃ dis.sɛt]) was the name of a "scheme of mobilisation and concentration" which the French Conseil Supérieur de la Guerre (the peacetime title of the French Grand Quartier Général) developed from 1912 to 1914, to be put into effect by the French Army in the event of war between France and Germany. The plan was for the mobilisation, concentration and deployment of the French armies to make possible an invasion either of Germany or of (neutral) Belgium or of both, before Germany completed the mobilisation of its reserves simultaneous with an expected Russian offensive.

The French generals implemented the plan from 7 August 1914, with disastrous consequences for their armies, which suffered defeat in the Battle of the Frontiers (7 August – 13 September) at a cost of 329,000 casualties. The French armies (and the British Expeditionary Force) in Belgium and northern France were forced into a retreat as far as the Marne river, where at the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September), the German armies were defeated and forced to retreat to the Aisne river, eventually leading to the Race to the Sea.

Background

Concentration plans 1871–1911

After the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War 1870–1871, from 1874–1880, General Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières (20 May 1815 – 16 February 1895) oversaw the construction of the Séré de Rivières system, a line of fortresses 65 km (40 mi) long from Belfort to Épinal and another line of similar length from Toul to Verdun, about 40 km (25 mi) back from the frontier. The River Meuse flows northwards from Toul to Verdun, Mézières and Givet on the Belgian border and a tributary of the Moselle between Belfort and Épinal, near parallel to the 1871–1919 French-German border. The Trouée de Charmes (Charmes Gap), 70 km (43 mi) wide, between Épinal and Toul was left unfortified and the fortress city of Nancy was to the east, 12 km (7.5 mi) from the German frontier. A second series of fortifications, to prevent the main line being outflanked, was built in the south, from Langres to Dijon and in the north from La Fère to Rheims and from Valenciennes to Maubeuge, although for financial reasons these defences were incomplete in 1914.[1]

During the 1870s, the French army drew up concentration plans according to a defensive strategy, which exploited the Meuse and branches of the Moselle parallel to the 1871 border. The completion of the fortress lines between Belfort and Verdun in the late 1880s and railway building from the interior to the border, then gave the French army the means to contemplate a defensive-offensive strategy, in which a German attack would be repulsed and then followed up by a counter-attack. In August 1891, Plan XI was completed, with an option for an offensive as well as a defensive strategy from the start, to exploit the opportunity created by the improvement in relations between the Third Republic and the Russian Empire. The Franco-Russian Alliance (1892–1917) led to Plan XII in February 1892, in which an immediate invasion of Germany was considered possible. But from Plan XI to Plan XVI, the strategy remained defensive-offensive, French attacks being expected after the repulse of a German invasion.[1]

In 1888, the French began to study a possible German offensive north of Verdun or through Belgium and Plan XII was written with a contingency for a German breach of Belgian neutrality. In 1904, this was given more attention after a German (Le vengeur [The Avenger]) sold a copy of the German concentration plan to French intelligence and described mobilisation methods and war plans. Using this windfall and other sources of information, the French adapted Plan XV of 1906, to be ready for a German invasion of Belgium and later plans contained increases in the forces to be assembled to the north and north-east of Verdun. Plan XVI of March 1909, anticipated a German enveloping manoeuvre through Luxembourg and Belgium, after the findings of a 1908 analysis by General Henri de Lacroix, in which he dwelt on the German preference for enveloping manoeuvres and predicted that two German armies would march through eastern Belgium, around the northern flank of the French fortress zone, one to emerge from the Ardennes at Verdun and the other at Sedan. Lacroix wanted to improve the prospects of the usual defensive-offensive strategy by assembling a new Sixth Army near Châlons-sur-Marne, (now Châlons-en-Champagne), 80 km (50 mi) west of Verdun, easily to move towards Toul in the centre, Verdun on the left or to the vicinity of Sedan and Mézières behind the northern flank.[2]

Prelude

Concentration plans, 1911–1914

General Victor-Constant Michel, Vice-President of the Conseil supérieur de la guerre in 1910, was more convinced than Lacroix of a German move through Belgium, because of the obstacle of French defences in Lorraine, the terrain in eastern Belgium and German railway building. Michel thought that the Germans would make their main effort in central Belgium and that covering a longer front would need the organisation of French reserve units and integration with the active army. The council rejected his view in 1911, which caused Michel to resign as he considered that deployment from Belfort to Mézières and an offensive towards Antwerp, Brussels and Namur as the only possible way to respond. Joseph Joffre was eventually appointed and the functions of Vice-President of the Council and Chief of Staff of the army were combined. In October 1911, a strategic assessment was delivered as part of a comprehensive review conducted from 1911–1912.[3]

Joffre had rewritten Plan XVI by 6 September, increasing the number of troops on the Belgian frontier (although not by as much as Michel had advocated), by shifting forces from the Italian border and incorporating second line and reserve units into the front line. The Fifth Army was to assemble further left to Mézières and the Sixth Army was to move closer to Verdun and the Belgian border west of Luxembourg. The amended version of Plan XVI put seven corps close to Belgium, which guarded against a German advance around Verdun or as far as Verdun or Mézières and Joffre increased emphasis on an immediate offensive.[4] Joffre continued to work on the plan and the possibility of a German move through Belgium, in which three alternatives were inferred, that the Germans would respect Belgian and Luxembourgeois neutrality and attack the Belfort–Épinal and Toul–Verdun lines or advance through Luxembourg in the vicinity of Verdun, then make a smaller attack into Belgium or defend in Lorraine and attack through Belgium. The third possibility was considered likely, because the French knew that a recent German war game had used the German fortifications around Metz and Thionville. German improvements to the fortifications at Metz and Thionville, led Joffre to believe that the Germans certainly would attack through Belgium and also that Belgium was the only place where France could fight a decisive battle against Germany.[5]

On 9 January 1912, the Conseil supérieur de la guerre agreed that the French army could enter Belgium but only when news had arrived that the Germans had already done so. The council also considered industrial mobilisation and the slow speed of the development of heavy artillery and agreed to increase the ammunition stock from 1,280 shells-per-gun to 1,500. Soon afterwards, command of the French army was centralised by abolishing the army Chief of Staff and vesting the powers in Joffre as Chief of the General Staff but Joffre's attempts to gain permission to ignore Belgian neutrality were rebuffed. An offensive strategy required an adequate field of operations and Belgium was the only place where the terrain was suitable but Belgian and British sensitivities remained paramount.[5] French politicians feared that violating Belgian sovereignty would force Belgium to join Germany in the event of war and cause Britain to withdraw from its military commitments.[6]

Despite the matter of Belgian neutrality, Joffre remained favourable to an offensive (rather than defensive-offensive) strategy and the benefit of compelling the Germans to fight against both France and Russia. Since 1894, the alliance with Russia had included a convention that both countries would treat Germany as the principal enemy, which was reaffirmed in 1910 and in subsequent staff talks. Joffre indicated that the French army would attack in the north-east and the desirability of a concurrent Russian offensive but still considered a French attack in Lorraine a possibility.[7] For political purposes, Joffre hid his intentions from the French government, the Plan XVII included deployments near southern Belgium but did not explicitly prepare to cross the Belgian frontier. Joffre considered an advance into Belgium to be 'France's "most desireable" course of action'.[8]

Plan XVII

After the changes to Plan XVI in September 1911, Joffre and the staff took eighteen months to revise the French concentration plan, the concept of which was accepted on 18 April 1913. Copies of Plan XVII were issued to army commanders on 7 February 1914 and the final draft was ready on 1 May. It 'was, in fact, no more than a plan for the mobilisation and initial concentration and deployment of the French army'.[9] The document was not a campaign plan but it contained a statement that the Germans were expected to concentrate the bulk of their army on the Franco-German border and might cross before French operations could begin. The instruction of the Commander in Chief was that

Whatever the circumstances, it is the Commander in Chief's intention to advance with all forces united to the attack of the German armies. The action of the French armies will be developed in two main operations: one, on the right in the country between the wooded district of the Vosges and the Moselle below Toul; the other, on the left, north of a line Verdun–Metz. The two operations will be closely connected by forces operating on the Hauts de Meuse and in the Woëvre.

— Plan XVII[10]

and that to achieve this, the French armies were to concentrate, ready to attack either side of Metz–Thionville or north into Belgium, in the direction of Arlon and Neufchâteau.[11] An alternative concentration area for the Fourth and Fifth armies was specified, in case the Germans advanced through Luxembourg and Belgium but an enveloping attack west of the Meuse was not anticipated; the gap between the Fifth Army and the North Sea was covered by Territorial units and obsolete fortresses.[12] Beyond force concentration, the plan left 'an enormous amount of control over the use and deployment of armed forces' to Joffre at the start of war.[13]

Aftermath

Battle of the Frontiers

| Battle | Date |

|---|---|

| Battle of Mulhouse | 7–10 August |

| Battle of Lorraine | 14–25 August |

| Battle of the Ardennes | 21–23 August |

| Battle of Charleroi | 21–23 August |

| Battle of Mons | 23–24 August |

When Germany declared war, France began Plan XVII with five initiatives, later named the Battle of the Frontiers. The German deployment plan, Aufmarsch II, included the massing of German forces (less 20 per cent to defend Prussia and the German coast) on the German–Belgian border. The force was used to execute an offensive into Belgium, to force a decisive battle on the French army on territory further north than the fortified Franco-German border.[15] The French began to implement Plan XVII with a deployment for an offensive into Alsace-Lorraine and Belgium. French strategy required the Russians to be brought into action as quickly as possible: 'to do so Joffre had promised to launch his own attack at the earliest opportunity [and] had no choice but to attack across the common frontier in Alsace and Lorraine'.[16]

The French attack into Alsace-Lorraine was defeated because of inadequate tactics, a lack of artillery-infantry co-operation and by the fighting capacity of the German armies, which inflicted huge numbers of casualties. French formations moved forward with insufficient reconnaissance.[13] The attacks in southern Belgium were conducted with negligible reconnaissance or artillery support and were repulsed without preventing the western manoeuvre of the German armies in the north.[17] While the attacks in the Ardennes starting on 22 August achieved strategic surprise in heavy fog, the French columns advancing were themselves unprepared and surprised by German presence in the area and were unable to attack due to a breakdown in command and control.[18]

Within a few days the French were back in their starting positions, having suffered a costly defeat.[19] The Germans advanced through Belgium and northern France against the Belgian, British and French armies and reached an area 30 km (19 mi) to the north-east of Paris but failed to trap the Allied armies and force a decisive battle on them. The German advance outran its supplies and slowed; Joffre was able to use French railways to move the retreating armies and re-group behind the river Marne and within the Paris fortified zone, faster than the Germans could pursue. The French defeated the faltering German advance with a counter-offensive at the First Battle of the Marne, assisted by the British.[20] Helmuth von Moltke the Younger, Chief of the German General Staff, had tried to apply the offensive strategy of Aufmarsch I (a plan for a Franco–German war, with all German forces deployed against France), to the inadequate western deployment of Aufmarsch II (only 80 per cent of the army assembled in the west), to counter the French offensive of Plan XVII. In 2014, Terry Holmes wrote,

Moltke followed the trajectory of the Schlieffen plan [sic], but only up to the point where it was painfully obvious that he would have needed the army of the Schlieffen plan [sic] to proceed any further along these lines. Lacking the strength and support to advance across the lower Seine, his right wing became a positive liability, caught in an exposed position to the east of fortress Paris.[21]

Analysis

The French offensive was defeated in a few days; on the right the First and Second armies advanced on 14 August and were back at their jumping-off points on 20 August. The offensive of the Third and Fourth armies was defeated from 21 to 23 August and the Fifth Army was defeated on the Sambre and forced to retreat during the same period. Joffre's strategy had failed due to an underestimation of the German armies and the dispersion of the French offensive effort. With a large German force operating in Belgium, the German centre had appeared to be vulnerable to the Third and Fourth armies. The mistaken impression of the size of the German force in Belgium or its approach route, was not as significant as underestimates on the strength of the German armies opposite the Third and Fourth armies near Luxembourg.[22] When the offensives failed, Joffre laid blame on his subordinates, finding 'grave shortcomings on the part of commanders' and claimed that the French infantry had failed to show offensive spirit, despite outnumbering the German armies at their most vulnerable point, a claim that Robert A. Doughty called "pure balderdash".[23]

The reality was that many of the French casualties were said to have come from an excess of offensive vigour and on 23 August, General Pierre Ruffey concluded that the infantry had attacked without artillery preparation or supporting-fire during the battle.[22] Early on 24 August, Joffre ordered a withdrawal to a line from Verdun to Mézières and Maubeuge and began to transfer troops from the east, opposite the German border, to the western flank. The French armies were to destroy railway facilities and inflict as many casualties as possible on the German armies while retreating, preparatory to resuming the offensive. Two strategic alternatives were possible, to attack the eastern flank of the 1st Army or to envelop the western flank of all the German armies. On 25 August, Joffre issued General Instruction No. 2, for a withdrawal to a line from Verdun to Reims and Amiens and the assembly of two corps and four reserve divisions near Amiens, to carry out the envelopment operation. Joffre called for much greater integration of the infantry and artillery and for more tactical dispersal of infantry to nullify German fire power.[24]

The assumptions of Joffre's pre-war strategy were proved wrong. Joffre assumed that the Germans would not push westward across Belgium into the French rear, confining themselves to eastern Belgium and that the Germans would not integrate reserve battalions into their front line units.[25][a] The German advance across Belgium forced the French into hurried redeployments. German integration of reserve battalions also meant that the German extension across Belgium would not weaken the German centre as Joffre expected, "instead of encountering a weakened center in eastern Belgium... French forces struck large enemy units in strong defensive positions". Joffre's need to comply with the terms of the Franco-Russian alliance forced him to launch offensives into the Vosges, splitting his forces and weakening any possible offensive manoeuvre.[27]

Casualties

In The World Crisis (1923–1931), Winston Churchill used data from French 1920 parliamentary records for French casualties from 5 August to 5 September 1914, which recorded 329,000 killed, wounded and missing. Churchill gave German casualties from August to November as 677,440 and British casualties from August to September of 29,598 men.[28] By the end of August, the French Army had suffered 75,000 dead, of whom 27,000 had been killed on 22 August. French casualties for the first month of the war were 260,000, of which 140,000 occurred during the last four days of the Battle of the Frontiers.[29] In 2009, Holger Herwig recorded German casualties in the 6th Army for August of 34,598, with 11,476 men killed, along with 28,957 more in September, 6,687 of them killed. The 7th Army had 32,054 casualties in August, with 10,328 men killed and 31,887 casualties in September with 10,384 men killed. In the 1st Army in August there were 19,980 casualties including 2,863 men killed and in the 2nd Army 26,222 casualties. In the last ten days of August, the 1st Army had 9,644 casualties and the 2nd Army suffered 15,693 casualties.[30] Herwig wrote that the French army did not publish formal casualty lists but that the French Official History Les armées françaises dans la grande guerre gave casualties of 206,515 men for August and 213,445 for September.[31]

Notes

- ^ Simon J. House believed that the domination of operations staff over intelligence staff in the French army was to blame for this oversight in thinking, 'Those operational staff officers could not believe that, as a matter of principle, the Germans would do anything that they themselves would not do. French reserve divisions were poorly trained and unfit to enter the line of battle; so, by definition, German reserve divisions had to be the same'.[26]

Footnotes

- ^ a b Doughty 2005, p. 12.

- ^ Doughty 2005, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Doughty 2005, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Doughty 2005, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b Doughty 2005, pp. 19–22.

- ^ Doughty 2003, p. 440.

- ^ Doughty 2005, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Doughty 2003, pp. 440–441.

- ^ House 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Edmonds 1926, p. 446.

- ^ Doughty 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Edmonds 1926, p. 17.

- ^ a b Krause 2014a, p. 28.

- ^ Doughty 2005, pp. 55–63, 57–58, 63–68.

- ^ Zuber 2010, p. 14.

- ^ House 2014, p. 9.

- ^ Zuber 2010, pp. 154–157.

- ^ House 2014, pp. 15, 21.

- ^ Zuber 2010, pp. 159–167.

- ^ Zuber 2010, pp. 169–173.

- ^ Holmes 2014, p. 211.

- ^ a b Doughty 2005, pp. 71–76.

- ^ Doughty 2005, p. 71.

- ^ Doughty 2005, pp. 76–78; Tuchman 1994, p. 309.

- ^ Doughty 2003, p. 453.

- ^ House 2014, p. 12.

- ^ Doughty 2003, p. 454.

- ^ Churchill 1938, pp. 1423–1425.

- ^ Stevenson 2004, p. 54.

- ^ Herwig 2009, p. 156.

- ^ Herwig 2009, pp. 217–219, 315.

References

Books

- Churchill, W. S. C. (1938) [1923–1931]. The World Crisis (Odhams ed.). London: Thornton Butterworth. OCLC 4945014.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1926). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523.

- Herwig, H. (2009). The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle that Changed the World. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6671-1.

- Krause, Jonathan, ed. (2014). The Greater War: Other Combatants and Other Fronts, 1914–1918. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-36065-6.

- House, S. "The Battle of the Ardennes, August 1914: France's Lost Opportunity". In Krause (2014).

- Krause, J. "Only Inaction Is Disgraceful': French Operations under Joffre, 1914–1916". In Krause (2014a).

- Stevenson, D. (2004). 1914–1918: The History of the First World War. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-026817-1.

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (1994) [1962]. The Guns of August (repr. ed.). New York: Ballantine. ISBN 978-0-30756-762-8.

- Zuber, T. (2010). The Real German War Plan 1904–14 (e-book ed.). Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5664-5.

Journals

- Doughty, Robert A. (2003). "French Strategy in 1914: Joffre's Own". The Journal of Military History. 67 (2). Project Muse: 427–454. doi:10.1353/jmh.2003.0112. ISSN 1543-7795. S2CID 154988802.

- Holmes, T. M. (April 2014). "Absolute Numbers: The Schlieffen Plan as a Critique of German Strategy in 1914". War in History. 21 (2). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage: 193–213. doi:10.1177/0968344513505499. ISSN 0968-3445. S2CID 159518049.

Further reading

Books

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2013). Der Weltkrieg: 1914 The Battle of the Frontiers and Pursuit to the Marne (Part 1). Germany's Western Front: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. Vol. I (1st ed.). Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-373-7.

- Keiger, J. F. V. (1983). France and the Origin of the First World War. The Making of the Twentieth Century. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-333-28552-7.

- Kennedy, P. M. (1979). The War Plans of the Great Powers, 1880–1914. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-940056-6.

- Porch, D. (1981). The March to the Marne: The French Army 1871–1914. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54592-1 – via Archive Foundation.

- Ritter, G. (1958). The Schlieffen Plan, Critique of a Myth (PDF). London: O. Wolff. ISBN 978-0-85496-113-9. Retrieved 1 November 2015 – via gwpda.org.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. Vol. I. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

Journals

- Cole, Ronald H. (1979). "Victor Michel: The Unwanted Clairvoyant of the French High Command". Military Affairs. 43 (4). JSTOR: 199–201. doi:10.2307/1986754. ISSN 0026-3931. JSTOR 1986754.

- Flammer, P. M. (1966–1967). "The Schlieffen Plan and Plan XVII: A Short Critique". Military Affairs. 30 (4). Washington, DC: American Military Institute: 207–212. doi:10.2307/1985401. ISSN 2325-6990. JSTOR 1985401.

- Kiesling, Eugenia (2010). "Strategic Thinking: The French Case in 1914 (& 1940)". Journal of Military and Strategic Studies. 13 (1). Calgary, Canada: Centre for Military and Strategic Studies. ISSN 1488-559X. Retrieved 30 November 2014.[permanent dead link]

- Porch, Douglas (2006). "French War Plans, 1914: The Balance of Power Paradox". The Journal of Strategic Studies. 29 (1). London: Taylor & Francis: 117–144. doi:10.1080/01402390600566423. ISSN 1743-937X. S2CID 154040473.

Theses

- House, S. J. (2012). The Battle of the Ardennes 22 August 1914 (PhD). London: King's College London, Department of War Studies. OCLC 855693494. Retrieved 3 November 2015 – via e-theses online service.