Pierre Arnoul

Pierre Arnoul | |

|---|---|

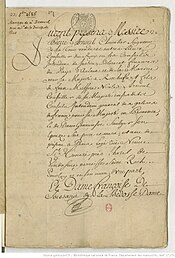

Portrait of Pierre Arnoul as Honorary Advisor to the Parlement de Provence. Engraving by Jacques Cundier after a painting by Nicolas de Largillierre.

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts | |

| Born | 1651 |

| Died | October 17, 1719 Paris |

| Occupation | Officier de plume |

| Spouse(s) | Françoise de Soissan de La Bédosse, Marie-Henriette Brodart |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Nicolas-François Arnoul de Vaucresson (brother) |

| Signature | |

Pierre Arnoul, born in 1651 and died in Paris on October 17, 1719, was a French officer de plume who served as the naval intendant during the reign of Louis XIV. He was the son of naval intendant Nicolas Arnoul and a study companion and friend of Seignelay, the son and successor of Jean-Baptiste Colbert. After succeeding his father as Secretary of State for the Navy, Pierre Arnoul was under the protection of Seignelay, his superior.

Pierre Arnoul's career, which spanned nearly fifty years, began with the support of his father and his connections to the Colbert family. It experienced a brief setback in 1679–1680 when he was dismissed following the sinking of two ships.

After studying the navies of foreign countries, he held various naval intendant positions in France, including in the Levant and the Ponant regions. He oversaw the administration of ports such as Marseille (1673–1674, 1710–1719), with a focus on the galley arsenal, Toulon (1674–1679), Le Havre (1680–1681), Bayonne (1681), and Rochefort (1683–1688). Moreover, he organized classes and supplied the Spanish fleet during the War of the Spanish Succession.

In the ports under his management, he oversaw daily operations and also spearheaded several significant developments. Despite proposing numerous projects to successive navy ministers, only a few were implemented. He was regarded as one of the most skilled naval administrators during Louis XIV's reign.

His first wife, Françoise de Soissan de La Bédosse, manipulated the entire Arnoul family. She first married her two sons, one to Pierre Arnoul's mother and the other to Pierre Arnoul's sister, before marrying Pierre Arnoul himself, despite being significantly older than him. She skillfully managed their assets. After her death, Pierre Arnoul remarried Marie-Henriette Brodart, the daughter of an intendant.

A family under the influence

The Arnouls, a family of maritime intendants

Pierre Arnoul hailed from a family of maritime intendants. His father, Nicolas Arnoul, served as the galley intendant in Marseille and later in Toulon, with his career being supported by Colbert.[DR 1] Nicolas married Geneviève Saulger, the daughter of Pierre Saulger, an office records keeper, in 1643.[Del 1] Pierre's brother, Nicolas-François Arnoul de Vaucresson, took over as the galley intendant in Marseille after a stint in the Caribbean islands.[DR 1]

Pierre Arnoul's nobility was confirmed by decree on October 24, 1705.[Del 1] He held the titles of Lord of Vaucresson, La Tour-Ronde, Haute-Borne, Pierrebelle, Rochegude, and Lagarde-Paréol.[Bo 1]

Pierre Arnoul under the influence of the Lady of Rus

Pierre Arnoul's parents, Nicolas Arnoul and his wife Geneviève, met Françoise de Soissan de La Bédosse, also known as the Lady of Rus, in Digne in 1673, and they developed a friendship. It appears that she influenced the Count of Suze, her likely romantic partner, to transfer all his property to the Arnouls.[Bé 1] Pierre Arnoul eventually declined this donation in 1680. In 1674, Nicolas Arnoul suffered a stroke. The Lady of Rus then stepped in to assist Geneviève Saulger in caring for the paralyzed patient[Bé 2] and quickly assumed control of the Arnoul household.[Ra 1]

After Nicolas Arnoul's death on October 18, 1674, Pierre Arnoul and his mother entrusted the management of family affairs to Françoise de Soissan.[Ra 2] However, Françoise took advantage of the situation to enrich herself.[Ra 3] Mrs. Arnoul, a widow in her fifties, seemed to have a preference for younger men, which led Françoise to persuade her to marry her eldest son, twenty-six-year-old Joseph-Horace de Rafelis, lord of Saint-Sauveur, in 1676. Subsequently, in 1680, Françoise arranged the marriage of her second son, Pierre-Dominique de Rafélis, to Geneviève Arnoul, the daughter of Geneviève Saulger and Nicolas Arnoul. Following the death of her second husband in 1686, Françoise married Pierre Arnoul, despite warnings from Minister Seignelay, who was Pierre Arnoul's superior, about the multiple marriages within the family.[Ra 4] Françoise was fifty-five years old at the time of her marriage to the thirty-five-year-old Pierre Arnoul.[Bé 2]

Through these three marriages, Pierre Arnoul became the stepfather of Françoise's sons, as well as the son-in-law of the eldest and the brother-in-law of the youngest.[Del 1] Françoise de Soissan became the daughter-in-law of her eldest son and the sister-in-law of her youngest son. Her eldest son, Joseph-Horace de Rafélis, became the stepfather of his own mother and stepfather of his father-in-law. Françoise's younger son, Pierre-Dominique de Rafélis, became the brother-in-law of his own mother, the stepson of his brother, and the son-in-law of his sister-in-law.[Bé 2] Geneviève Saulger, Pierre Arnoul's mother, died on October 26, 1683, and her young widower remarried Catherine des Isnard.[Del 1]

Françoise de Soissan died on May 2, 1699, after a two-week illness. In her will, she assigns missions to Capuchin religious in Rochegude, Saint-Sauveur, and Beaumes. In the seigniory of Ruth (at Lagarde-Paréol, near Orange), which she inherited from her first husband, she collaborates with Pierre Arnoul to establish a pious and charitable institution. They fund the creation of "solitaires," or hermits, who care for children and teach them manual skills.[Bé 3] Following his wife's death, Pierre Arnoul details in a memorandum, written for a legal dispute with his sister Geneviève, the significant influence Françoise de Soissan had on the entire family. He even mentions the negative influence of the devil but also acknowledges her exceptional leadership qualities and the benefits he derived from them.[Bé 1]

In his second marriage, Pierre Arnoul married Marie-Henriette Brodart on October 17, 1704. She was the daughter of Jean-Baptiste Brodart, the galley intendant in Toulon in 1675 after Arnoul. He maintained his social status through this marriage.[DR 2] At the time, he was a wealthy man, owning a real estate complex in Marseille known as the Marquis de Villeneuve, which was leased out and included large warehouses near the arsenal, established by his father Nicolas Arnoul.[1] He also employed over a dozen servants in Paris. His second wife brought a significant dowry, and they had five children.[2]

Explaining the influence

In 1707, journalist Anne-Marguerite Petit du Noyer mentioned Françoise de Soissan in her Letters historiques et galantes, describing her as an "enchantress." She emphasizes that it is exceptional "to have been able to inspire such passionate and constant love at an age when one should only inspire disgust." Moreover, she provides a simple explanation: "Some believe her to be a witch, others a saint, and I believe she is neither, simply a skillful and clever woman who was aided by fortune."[Bé 4]

In the early twentieth century, Françoise de Soissan was viewed as a cunning and unscrupulous adventurer. Louis Delavaud depicts her as a manipulator who exploits the gullibility and obstinacy of the Arnoul family[Del 2] while acknowledging her seductive charm and strong will.[Del 3] Gaston Rambert describes her as crafty and avaricious, yet adept at persuading others without resorting to theatrics.[Ra 5] Paul-Marie Bondois suggests that the Arnoul family falls victim to the lady of Rus, who cunningly seizes their wealth.[Bo 2]

In 2021, historian Lucien Bély perceives Françoise de Soissan as a skilled and ambitious businesswoman. She adeptly gains the trust of others, engages in influence peddling, and effectively controls an entire family. Françoise lends money, intervenes in over three hundred notarized acts, and demonstrates a keen understanding of legal procedures to enhance her wealth.[Bé 5] She efficiently oversees Pierre Arnoul's affairs, as he is preoccupied with his responsibilities as naval intendant. Françoise excels as a manager and actively pursues the acquisition of lordships such as Saint-Sauveur and Rochegude.[Bé 6]

A career of nearly fifty years

Education and early positions (1670–1674)

The relationship between Jean-Baptiste Colbert and Pierre Arnoul was significant for the beginning of Colbert's career. It was a patron-client relationship, common in Ancien Régime society. Colbert supported Pierre, the son of Nicolas, out of respect for the father. He also did not hesitate to advise and guide his young protégé when needed.[3]

From 1670 to 1671, Pierre Arnoul was sent on a mission to Italy, Flanders, England, and Holland. During this time, he gained knowledge about shipbuilding, supply organization, refit, and tactics.[DR 3] As a result, he could provide detailed descriptions to Colbert about the Dutch construction techniques and their advantages, such as the use of wooden pegs instead of irons, commonly used by the French.[DR 4]

Upon his return in 1671, he was appointed as a naval commissioner in Toulon.[DR 3] In this role, he joined the French fleet in the Battle of Solebay against the Dutch, alongside their English allies. The battle resulted in severe losses for both sides, with an undecided outcome and conflicting claims of victory. Pierre Arnoul provided a detailed report on the battle, which did not assign blame to the commonly accused the Count of Estrées for the lack of success.[DT 1]

Arnoul assumed the role of controller general in Ponant in 1672. He returned to Provence as intendant of galleys in Marseille in 1673, when he was in his early twenties, succeeding his father Nicolas Arnoul. After a year in the city, he became intendant of the navy in Toulon in 1674, once again succeeding his father in this position.[DR 3]

Naval intendant in Toulon (1674–1679)

Pierre Arnoul served as the naval intendant in Toulon from 1674 to 1679,[DR 3] where he played a crucial role in overseeing various aspects of naval operations in the arsenal. This included managing shipbuilding, recruiting sailors, and handling armaments. His authority also extended to the management of the port, city, and the coastal region. He worked closely with the provincial intendant, with clearly defined responsibilities for each. Regular correspondence with the Secretary of State for the Navy was essential, as Arnoul received orders and reported back on his activities.[DR 5] However, Seignelay criticized Arnoul for not providing detailed written descriptions of his projects,[4] specifically requesting drawings with precise scales and dimensions for ship construction, including decorative elements.[5]

While still young, Pierre Arnoul was tasked with arming the Levant fleet, a challenging responsibility.[DR 6] He established a new dock in the port of Toulon and, in 1676, proposed the installation of sawmills inspired by those he had seen in the United Provinces.[DR 7] However, sourcing construction timber proved to be a significant challenge. It took over a year for the ordered timber to arrive in Toulon, transported by rafting from the forests of Burgundy and Franche-Comté.[DR 8] Additionally, Arnoul ordered wood from the Hautes-Alpes[6] and explored resources in Saint-Étienne, Saint-Gervais, and Nivernais in the late 1670s, particularly focusing on wood availability.[7]

In September 1678, he presented a detailed memorandum proposing a project to enhance the navigability of the Rhône's branches in its delta. He stressed the critical need for immediate action, as the shallow depth of the Rhône's branches hindered efficient navigation. However, this project was never implemented.[8]

To expedite ship construction, he efficiently coordinated the assembly of ships with master carpenters using prefabricated elements.[DR 9] At Colbert's behest, on July 14, 1679, he orchestrated the rapid assembly of a ship in just seven hours, a remarkable technical and logistical achievement. Colbert had presented this ambitious project to the three intendants of Brest, Rochefort, and Toulon in July 1678, aiming to impress the king and highlight the importance of the navy. Initially skeptical, Arnoul eventually embraced the challenge, overseeing the construction of a storage hall for ship components to streamline the process and conducting rehearsals before the successful "ship trial" in Toulon.[9] In the same year, 1679, he also initiated one of the first construction schools for the sons of master carpenters in Toulon, where they received instruction in drawing.[5]

From 1675 to 1679, when Toulon was the kingdom's premier naval arsenal, Arnoul concurrently managed shipbuilding, the outfitting of war squadrons, vessel maintenance, supply problems, personnel management, and accounting for over a third of the French naval forces.[DT 2]

A spectacular but brief dismissal (1679–1680)

He was dismissed in 1679 following the shipwrecks on October 19 and 21, 1679, in a storm, of two ships, the Prince and the Conquérant, belonging to the division commanded by Tourville off the coast of Brittany. These shipwrecks were dramatic: hundreds of sailors perished, and Tourville himself narrowly escaped by swimming. Seignelay was furious and accused Pierre Arnoul of being responsible for this tragedy due to improper refit on these ships.[DT 3] He wrote to him:

"You are responsible for the loss of two of the king's largest ships and over eight hundred men who were part of their crews. This incident, which has not occurred in other nations, will bring discredit to the navy among foreigners. You have also undermined all the efforts made to maintain good order in the Navy. Therefore, you must understand that the king can no longer employ you in your current position or any other position."[DT 3]

The anger of Colbert and his son is understandable as these shipwrecks resulted in more deaths than recent naval battles. Among the drowned were officers, including a nephew of Jean-Baptiste Colbert and a nephew of Tourville.[DT 3] The hull breaches that led to the losses of the Prince and the Conquérant were attributed to shoddy repairs carried out in Toulon, a similar incident involving the Florissant in 1677 further supports this notion. What is most concerning is that Seignelay had not detected these malfunctions during his visit to Toulon, placing the blame on Arnoul to avoid discrediting the ministers.[DT 4]

Seignelay dispatches Brodart, the naval intendant, and Duquesne to Toulon, where they confront Pierre Arnoul and accuse him of being responsible for the damages. Arnoul defends himself by pointing out the fast pace of work in the port and the risks of navigation. His culpability is ambiguous, and he is eventually dismissed in December 1679.[DT 5] Seignelay's decision to remove Arnoul serves as a symbolic gesture to the king, but the overall maintenance of the fleet suffers due to inadequate funding.[DR 10]

Naval intendant from Le Havre to Rochefort (1680–1688)

Pierre Arnoul's fall from grace was short-lived, likely due to his close connections with Seignelay. By 1680, Arnoul was appointed as the naval intendant in Le Havre.[DR 3] He focused on expanding the Royal School of Hydrography in Le Havre, which provided training for captain and boat pilot licenses. Under his leadership, the school saw a significant increase in the number of students.[10] In 1681, he became the intendant of the fortifications in Bayonne and, in 1682, he took on the same role for the island of Ré.[DR 3]

Pierre Arnoul assumed the role of naval intendant in Rochefort in 1683, arriving in January and serving until 1688.[Del 4] His duties extended beyond the port of Rochefort, as he held the official title of "intendant of justice, police, finance, navy, and fortifications and maritime places of the Rochefort department." This encompassed a wide range of responsibilities, including civil administration tasks such as justice, police, and financial management. His successor in 1688, Michel Bégon, had more limited functions in the port of Rochefort, possibly due to the looming War of the League of Augsburg.[11] The port and arsenal of Rochefort were established in the 1660s through the efforts of Colbert and his cousin Colbert de Terron.[12]

In 1683, Arnoul established a hospital in Rochefort, previously located in Tonnay-Charente, and placed it under the care of the Lazarists. He also reorganized religious life by creating a new parish.[Del 5] During the same year, he initiated the construction of a new dry dock with two basins, which was completed after he departed from Rochefort.[13] This dry dock has been designated as a historical monument since 1989.[14] Arnoul, like other naval intendants, focused on combating epidemics and implemented quarantine measures for ships arriving from Canada.[15] Around 1685, he supported a project to establish a stud farm in a forest near Rochefort, which was to be funded by private investors. However, this stud farm project did not come to fruition.[16]

After the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, Arnoul aimed to establish schools in the rural parishes of Saintonge and Aunis, which were heavily influenced by Protestantism. His goal was to educate children and convert them to Catholicism since Protestant schools had been closed following the revocation. However, he faced challenges such as a shortage of schoolmasters, insufficient funding, and resistance from parents. Arnoul also suggested the establishment of a university in La Rochelle to prevent the youth from leaving the region, but his proposal was not accepted by Versailles. Despite these obstacles, he made some progress in creating a school network through his determination and active involvement in the campaign.[17] In 1686, he proposed to Seignelay a solution to the navy's recruitment issues by recruiting ship carpenters and caulkers as seamen. Although this idea seemed promising, it was ultimately deemed impractical due to a lack of available manpower.[DR 11]

From Picardy to Class Administration (1688–1703)

He was transferred in 1688. During the War of the League of Augsburg, Pierre Arnoul served as the intendant of maritime fortifications in Picardy and the conquered territories.[DR 3]

In 1690, in collaboration with Michel Bégon, who succeeded him as intendant in Rochefort, he oversaw the construction of galleys from the Ponant, led by Marseille carpenters. He praised the result, describing shallow-draft boats designed for coastal navigation. Furthermore, he coordinated the transfer of crews and convict laborers from Marseille to Rochefort, via the Mediterranean Sea, the Canal du Midi, the Garonne, and the Gironde, totaling over 5,000 men. The transfer was organized in four detachments and took place from late March to mid-May.[Zy 1]

In 1690, the Marquis de Seignelay, Secretary of State for the Navy, died unexpectedly. This created a vacancy in the position. Pierre Arnoul, an expert on the navy along with François d'Usson de Bonrepaus, was considered for the role. However, Arnoul was seen as more of a technician and lacked the political experience required for the position. As a result, Louis of Phélypeaux, despite his limited maritime expertise, was appointed as the new Secretary of State for the Navy.[DT 6]

The health situation in Brest was dire at the time. In 1690, Tourville's fleet landed several thousand sick individuals there, some of whom were housed in private residences. In early 1691, Pierre Arnoul was dispatched on an inspection mission by the new minister. He recommended expanding the capacity of the Naval Hospital, a proposal that Pontchartrain readily approved. As a result, Brest was outfitted with a hospital capable of accommodating over 1,500 beds, commensurate with the size of its arsenal.[18]

In 1692, Arnoul succeeded Usson de Bonrepaus in overseeing the naval classes,[DT 6] a recruitment system for sailors established by Colbert in 1670. Under this system, each sailor is required to serve on naval vessels for one year out of three and is registered accordingly.[DR 12] Arnoul held the position of Inspector General of the classes for eighteen years.[Del 6]

In 1696, he drafted a memorandum outlining a proposed diplomatic chamber that would unite former ambassadors returning to Paris. They would be granted the title of Councillor of State, maintain connections with the current ambassador in their former post, offer advice to the minister, and contribute to the education of young diplomats. Although these ideas were never put into practice, they reflect a desire to organize diplomatic careers.[19]

In 1701, Pierre Arnoul penned a memorandum on the production of sugar in the West Indies, focusing on its role in colonial economic development and maritime trade. He compared the French sugar industry in the Antilles to its English counterpart, noting advancements. Arnoul suggested emulating English practices, such as lowering taxes, to boost sugar production in the Antilles. Additionally, he examined other colonial trade commodities like cocoa, tobacco, cotton, and indigo.[Bo 3]

From Andalusia to Marseille (1703–1719)

During the War of the Spanish Succession, Pierre Arnoul participated in the maritime defense of Spain and organized the supply of its fleet.[DR 3] He arrived in Spain in 1703[Del 7] and served as the intendant of maritime fortifications, being particularly active in Andalusia and managing the port of Cadiz.[20]

Pierre Arnoul served as the intendant of galleys in Marseille from 1710 until he died in 1719.[DR 3] During this period, he also held the position of trade intendant in Marseille, a role separate from the one in Aix-en-Provence. Arnoul claimed the title of "intendant of commerce in Provence"[21] and received a pension from the Marseille Trade Chamber.[2] Additionally, he was an honorary counselor in the Parliament of Provence.[22] In 1710, he was tasked by the king to resolve a significant financial dispute between privateer Jacques Cassard and the city of Marseille, a case that remained unresolved for an extended period.[23]

After the War of the Spanish Succession, French galleys were no longer in use. Pierre Arnoul, whose father Nicolas Arnoul had built the Marseille arsenal, decided to remove the grass that had grown due to lack of activity.[24] He then reinitiated the workers' operations, completed a galley, and oversaw a significant cleanup effort.[Zy 2]

In October 1715, the newly established Council of the Navy, as part of the polysynody, requested Pierre Arnoul to provide an account of his management of convicts on the galleys. The Council specifically asked for lists of released prisoners. Convicts sentenced to the galleys were frequently not released at the end of their terms, leading to complaints. After some delay, Pierre Arnoul finally submitted the requested information. As a result of the Naval Council's intervention, the duration of sentences was more strictly enforced, leading to improved survival rates for convicts with shorter terms.[Zy 3]

Pierre Arnoul died during a trip to Paris on October 17, 1719,[Del 7] while serving as an official in Marseille.[DR 3] Throughout his nearly fifty-year career, he held various positions in the navy, except for the intendancies of Brest and Dunkirk. His competence was unquestionable.[DR 3][25] After his death, his brother, Nicolas Arnoul de Vaucresson, took over as the intendant of the galleys.[2]

Nicolas de Largillierre painted a portrait of Pierre Arnoul, an honorary counselor in the Parliament of Provence. This portrait served as a model for an engraving created in 1727 by Jacques Cundier, now housed in the old collection of the Méjanes library in Aix-en-Provence.[22] The papers of Pierre Arnoul and his father, Nicolas, are preserved at the National Library of France. The collection primarily consists of correspondence between the Arnoul intendants and successive ministers such as Colbert, Seignelay, and Phélypeaux, providing valuable insights into France's political actions. Additionally, the collection includes private documents[26] showcasing the diverse tasks undertaken by Pierre Arnoul and his father.[27]

Heraldry

Azure, a fess or, accompanied in chief by three argent roses and in base by three interlaced crescents of the same.[Ra 6]

References

- Bély, Lucien (2021). Louis XIV, le fantôme et le maréchal-ferrant (in French). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-082747-4.

- Bondois, Paul-Marie (1934). "L'industrie sucrière française à la fin du xviie siècle. Les projets de l'intendant Pierre Arnoul". Revue d'histoire économique et sociale (in French). 22 (1/2): 67–92. ISSN 0035-239X. JSTOR 24066974.

- ^ Bondois 1934, p. 79.

- ^ Bondois 1934, p. 80-81.

- ^ Bondois 1934, p. 82-92.

- Delavaud, Louis (1912). "Les établissements religieux et hospitaliers à Rochefort 1683–1715". Archives Historiques de la Saintonge et de l'Aunis (in French). 43. Paris-Saintes: 1–113.

- ^ a b c d Delavaud 1912, p. 6.

- ^ Delavaud 1912, p. 5.

- ^ Delavaud 1912, p. 7.

- ^ Delavaud 1912, p. 2.

- ^ Delavaud 1912, p. 9-11.

- ^ Delavaud 1912, p. 3-4.

- ^ a b Delavaud 1912, p. 4.

- Dessert, Daniel (1996). La Royale. Vaisseaux et marins du Roi-Soleil (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-02348-9.

- ^ a b Dessert 1996, p. 51-52.

- ^ Dessert 1996, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Dessert 1996, p. 46-47.

- ^ Dessert 1996, p. 135-136.

- ^ Dessert 1996, p. 40-45.

- ^ Dessert 1996, p. 198.

- ^ Dessert 1996, p. 121.

- ^ Dessert 1996, p. 168-169.

- ^ Dessert 1996, p. 156.

- ^ Dessert 1996, p. 192-194.

- ^ Dessert 1996, p. 94.

- ^ Dessert 1996, p. 212-215.

- ^ Dessert 2002, p. 84-90.

- ^ Dessert 2002, p. 135-136.

- ^ a b c Dessert 2002, p. 127-132.

- ^ Dessert 2002, p. 136-139.

- ^ Dessert 2002, p. 142-148.

- ^ a b Dessert 2002, p. 250-253.

- Rambert, Gaston (1925). "Une aventurière à Marseille et à Toulon au xviie siècle. La dame de Rus". Provincia. Bulletin de la société de statistique de Marseille (in French). 5: 10–29.

- ^ Rambert 1925, p. 14-15.

- ^ Rambert 1925, p. 17-18.

- ^ Rambert 1925, p. 21-24.

- ^ Rambert 1925, p. 25-26.

- ^ Rambert 1925, p. 11.

- ^ Rambert 1925, p. 27

- Zysberg, André (1987). Les galériens. Vies et destins de 60 000 forçats sur les galères de France 1680–1748. L'univers historique (in French). Seuil. ISBN 2-02-009753-2.

- ^ Zysberg 1987, p. 276-281.

- ^ Zysberg 1987, p. 322.

- ^ Zysberg 1987, p. 371-372.

- Other references

- ^ Rambert, Gaston (1924). "Les origines du Marquisat de Villeneuve". Provincia. Bulletin de la société de statistique de Marseille (in French). 4: 29–52.

- ^ a b c Masson, Paul (1938). Les galères de France. Marseille port de guerre (1481–1781) (in French). Paris: Hachette. pp. 367–369.

- ^ Kettering, Sharon (1986). Patrons, Brokers, and Clients in Seventeenth-Century France. New York - Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-0-19-536510-8.

- ^ Sarmant, Thierry; Stoll, Mathieu (2019). Régner et gouverner. Louis XIV et ses ministres. Tempus (in French). Vol. 769. Paris: Perrin. p. 465. ISBN 978-2-262-08029-7.

- ^ a b Théron, Magali (May 25, 2018). "Les ateliers de peinture et de sculpture des arsenaux en Provence en marge de l'Académie de peinture et de sculpture de Marseille". Rives Méditerranéennes (in French). 56: 147–174. doi:10.4000/rives.5430. ISSN 2103-4001. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Billioud, J (1960). "Le bois des Hautes-Alpes en Provence". Bulletin de la Société d'études des Hautes-Alpes (in French). 52: 106–112.

- ^ Cabantous, Alain (2003). "L'initiative et la contrainte. Pouvoir royal, territoires et marine (1660–1700)". Revue du Nord (in French). 352 (4): 717–728. doi:10.3917/rdn.352.0717. ISSN 0035-2624. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Rambert, Gaston (1924). "Un projet d'aménagement du Rhône maritime au XVIIe siècle". Mémoires de l'Institut historique de Provence (in French). 1: 72–80.

- ^ Vérin, Hélène (1996). "14 juillet 1679. Un exploit technique". Gérer et comprendre. Série trimestrielle des Annales des Mines (in French). 42: 22–35.

- ^ Anthiaume, Albert (1910). "L'enseignement de la science nautique au Havre-de-Grâce pendant les xvie, xviie et xviiie siècles". Bulletin de géographie historique et descriptive (in French). 1–2: 92–107.

- ^ Le Mao, Caroline (2011). "Gérer un arsenal en temps de guerre : réflexions sur le rôle des intendants de marine lors de la guerre de la Ligue d'Augsbourg (1688–1697)". XVIIe Siècle. Bulletin de la Société d'étude du XVIIe siècle (in French). 253 (4): 695–708. ISSN 0012-4273. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ Acerra, Martine (2011). "La création de l'arsenal de Rochefort". XVIIe Siècle. Bulletin de la Société d'étude du XVIIe siècle (in French). 253 (4): 671–676. doi:10.3917/dss.114.0671. ISSN 0012-4273. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ "Exposition Le patrimoine classé de l'État en Charente-Maritime / Expositions / Actualités / Accueil – Les services de l'État en Charente-Maritime". www.charente-maritime.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on November 13, 2022. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ "Formes de radoub de l'arsenal". www.pop.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on November 13, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ Even, Pascal (2004). "Le mal venu de la mer". La violence et la mer dans l'espace atlantique : xiie – xixe siècle. Histoire (in French). Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes. pp. 357–372. ISBN 978-2-7535-0034-1.

- ^ Bondois, Paul-Marie (1929). "Un projet de création d'un haras à Rochefort au XVIIe siècle". Bulletin de la Société de géographie de Rochefort (in French). 40: 128–131.

- ^ Even, Pascal (2002). "La politique scolaire de l'intendant Pierre Arnoul". Revue de la Saintonge et de l'Aunis (in French). 28: 55–75.

- ^ Suberchicot, Jean-Luc (1997). "Contrainte sanitaire et grandes escadres : la flotte de Tourville à Béveziers". XVIIe Siècle. Bulletin de la Société d'étude du XVIIe siècle (in French). 49 (196): 455–478.

- ^ Thuillier, Guy (1989). "Aux origines de l'académie politique de Louis XIV. Le projet de Pierre Arnoul (1696 ?)". La Revue administrative (in French). 42 (247): 15–18. ISSN 0035-0672. JSTOR 40781777. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ Désos, Catherine (2009). Les Français de Philippe V : Un modèle nouveau pour gouverner l'Espagne (1700–1724). Sciences de l'histoire (in French). Strasbourg: Presses universitaires de Strasbourg. ISBN 978-2-86820-391-5.

- ^ Frostin, Charles (2006). Les Pontchartrain, ministres de Louis XIV : Alliances et réseau d'influence sous l'Ancien Régime. Histoire (in French). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. pp. 390–391. ISBN 978-2-7535-0289-5.

- ^ a b Vasselin, Martine (2002). "Les portraits gravés des membres du Parlement d'Aix". Le Parlement de Provence 1501–1790 (in French). Aix-en-Provence: Presses universitaires de Provence. pp. 91–115. ISBN 978-2-85399-509-2.

- ^ Hrodej, Philippe (2002). Jacques Cassard. Armateur et corsaire du Roi-Soleil. Histoire (in French). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. pp. 86–88. ISBN 2-86847-657-0.

- ^ Zysberg, André (2011). "L'arsenal, cité des galères à Marseille au siècle de Louis XIV". XVIIe Siècle. Bulletin de la Société d'étude du XVIIe siècle (in French). 253 (4): 639–656. doi:10.3917/dss.114.0639. ISSN 0012-4273. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Dessert, Daniel (1995). Patronages et clientélismes 1550–1750 (France, Angleterre, Espagne, Italie). Histoire et littérature du Septentrion (IRHiS) (in French). Lille: Publications de l’Institut de recherches historiques du Septentrion. pp. 69–83. ISBN 978-2-905637-92-5.

- ^ Latouche, Robert (1908). "Inventaire sommaire de la collection Arnoul conservée à la Bibliothèque nationale". Revue des Bibliothèques (in French). 18 (1–3): 244–248.

- ^ Theron, Magali (2003). "Sur dix figures en cire disparues de Pierre Puget. Le fonds Arnoul des manuscrits de la Bibliothèque nationale". Bulletin de la Société de l'Histoire de l'Art français (in French): 151–167.

See also

- Anne Hilarion de Tourville

- Jean Baptiste Colbert, Marquis of Seignelay

- Officier de plume

- Bagne (penal establishment)

- Françoise de Soissan de La Bédosse

External links

Research resource: "Persée" (in French).