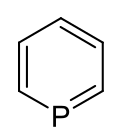

Phosphorine

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name Phosphinine[1] | |||

| Other names Phosphabenzene | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChemSpider | |||

| MeSH | Phosphinine | ||

PubChem CID |

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C5H5P | |||

| Molar mass | 96.069 g·mol−1 | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related -ines |

|||

Related compounds |

Phosphole | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

Phosphorine (IUPAC name: phosphinine) is a heavier element analog of pyridine, containing a phosphorus atom instead of an aza- moiety. It is also called phosphabenzene and belongs to the phosphaalkene class. It is a colorless liquid that is mainly of interest in research.

Phosphorine is an air-sensitive oil[2] but is otherwise stable when handled using air-free techniques (however, substituted derivatives can often be handled under air without risk of decomposition).[3][4] In contrast, silabenzene, a related heavy-element analogue of benzene, is not only air- and moisture-sensitive but also thermally unstable without extensive steric protection.

History

The first phosphorine to be isolated is 2,4,6-triphenylphosphorine. It was synthesized by Gottfried Märkl in 1966 by condensation of the corresponding pyrylium salt and phosphine or its equivalent ( P(CH2OH)3 and P(SiMe3)3).[3]

The (unsubstituted) parent phosphorine was reported by Arthur J. Ashe III in 1971.[2][5] Ring-opening approaches have been developed from phospholes.[6]

Structure, bonding, and properties

Structural studies by electron diffraction reveal that phosphorine is a planar aromatic compound with 88% of aromaticity of that of benzene. Potentially relevant to its high aromaticity are the well matched electronegativities of phosphorus (2.1) and carbon (2.5). The P–C bond length is 173 pm and the C–C bond lengths center around 140 pm and show little variation.[7]

|

Although phosphorine and pyridine are structurally similar, phosphorines are far less basic. The pKa of C5H5PH+ and C5H5NH+ are respectively −16.1 and +5.2. The P-oxides are extremely unstable, rapidly adding nucleophiles to a species tetracoordinate at phosphorus. Strongly backbonding Lewis acids (e.g. tungsten pentacarbonyl) can stabilize a dative bond from phosphorus.[6]

Both electrophiles and strong, hard nucleophiles preferentially attack at phosphorus, but the ring aromaticity is sufficiently weak that the result is an addition reaction, and not aromatic substitution.[6] Thus for example methyllithium adds to phosphorus in phosphorine whereas it adds to the 2-position of pyridine.[8] Halophosphorines do undergo noble-metal- or zirconocene-catalyzed substitution, and λ5-phosphorines exhibit a much more traditional substitution chemistry.[6]

Unlike arsabenzene, phosphorine rarely participates in Diels-Alder-type cycloadditions; when it does, the coupling partner must be an extremely electron-poor alkyne. Phosphorine complexes are tolerable Diels-Alder reactants.[6]

Coordination chemistry

Coordination complexes bearing phosphorine as a ligand are known. Phosphorines can bind to metals through phosphorus center. Complexes of the diphospha analogue of 2,2′-bipyridine are known. Phosphorines also form pi-complexes, illustrated by V(η6-C5H5P)2.[6]

See also

- Six-membered aromatic rings with one carbon replaced by an element from another group: borabenzene, silabenzene, germabenzene, stannabenzene, pyridine, phosphorine, arsabenzene, stibabenzene, bismabenzene, pyrylium, thiopyrylium, selenopyrylium, telluropyrylium

References

- ^ IUPAC Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Division (2013). Favre, Henri A.; Powell, Warren H. (eds.). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. IUPAC–RSC. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4. p. 47.

- ^ a b Ashe, A. J. (1971). "Phosphabenzene and Arsabenzene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 93 (13): 3293–3295. doi:10.1021/ja00742a038.

- ^ a b G. Märkl, 2,4,6-Triphenylphosphabenzol in Angewandte Chemie 78, 907–908 (1966)

- ^ Newland, R. J.; Wyatt, M. F.; Wingad, R. L.; Mansell, S. M. (2017). "A ruthenium(II) bis(phosphinophosphinine) complex as a precatalyst for transfer-hydrogenation and hydrogen-borrowing reactions". Dalton Transactions. 46 (19): 6172–6176. doi:10.1039/C7DT01022B. hdl:1983/8ceafa01-697c-4055-bd9f-3bfcb60d93f2. ISSN 1477-9226. PMID 28436519.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Mathey, François (2011). "Phosphorus Heterocycles" in Modern Heterocyclic Chemistry, 1st ed., edited by Álvarez-Builla, Julio; José Vaquero, Juan; and Barluenga, José. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. §23.3. doi:10.1002/9783527637737.ch23.

- ^ László Nyulászi "Aromaticity of Phosphorus Heterocycles" Chem. Rev., 2001, volume 101, pp 1229–1246. doi:10.1021/cr990321x

- ^ Ashe III, Arthur J.; Smith, Timothy W. "The reaction of phosphabenzene, arsabenzene and stibabenzene with methyllithium." Tetrahedron Letters 1977, volume 18, pp. 407–410. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)92651-6

- Quin, L. D. (2000). A Guide to Organophosphorus Chemistry. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-31824-8.