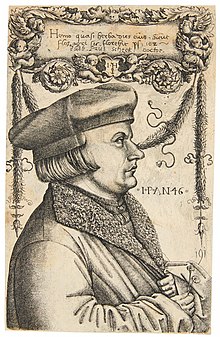

Johannes Pfefferkorn

Johannes Pfefferkorn (original given name Joseph; 1469, Nuremberg – Oktober 22, 1521, Cologne) was a German Catholic theologian and writer who converted from Judaism.[1][2] Pfefferkorn actively preached against the Jews and attempted to destroy copies of the Talmud, and engaged in a long running pamphleteering battle with humanist Johann Reuchlin.

Early life

Born a Jew, possibly in Nuremberg,[3] Pfefferkorn lived in Nuremberg and moved to Cologne after many years of wandering.[3] After committing a burglary, he was imprisoned and released in 1504.[4] He converted to Catholic Christianity in 1505 and was baptized[3] together with his family.[3]

Writings concerning the Jews

Pfefferkorn became an assistant to the prior of the Dominican friars at Cologne, Jacob van Hoogstraaten, and under the auspices of the Dominicans published several pamphlets in which he tried to demonstrate that Jewish religious writings were hostile to Christianity.[4]

In Der Judenspiegel (Cologne, 1507), he demanded that the Jews should give up the practice of what the Church deemed usury (lending money against interest), work for their living, attend Christian sermons, and do away with the books of the Talmud.[3] On the other hand, he condemned the persecution of the Jews as an obstacle to their conversion, and, in a pamphlet, Warnungsspiegel,[4] defended them against charges of murdering Christian children for ritual purposes.[3] In Warnungsspiegel, he professed to be a friend of the Jews, and desired to introduce Christianity among them for their own good.[4] He urged them to convince the Christian world that the Jews do not need Christian blood for their religious rites and advocated seizing the Talmud by force from them.[4] "The causes which hinder the Jews from becoming Christians," he wrote, "are three: first, usury; second, because they are not compelled to attend Christian churches to hear the sermons; and third, because they honor the Talmud."[4]

Bitterly opposed by the Jews on account of this work, he virulently attacked them in Wie die blinden Jüden ihr Ostern halten (1508); Judenbeicht (1508); and Judenfeind (1509).[3] In his third pamphlet he contradicted what he had written earlier and insisted that every Jew considers it a good deed to kill, or at least to mock, a Christian; therefore he deemed it the duty of all true Christians to expel the Jews from all Christian lands; if the law should forbid such a deed, they do not need to obey it: "It is the duty of the people to ask permission of the rulers to take from the Jews all their books except the Bible...."[4] He preached that Jewish children should be taken away from their parents and educated as Catholics. In conclusion, he wrote: "Who afflicts the Jews is doing the will of God, and who seeks their benefit will incur damnation."[4] In the fourth pamphlet, Pfefferkorn declared that the only way to get rid of the Jews was either to expel or enslave them; the first thing to be done was to collect all the copies of the Talmud found among the Jews and to burn them.[4]

Criticism of Hebrew texts

Convinced that the principal source of the obduracy of the Jews lay in their books, he tried to have them seized and destroyed.[3] He obtained from several Dominican convents recommendations to Kunigunde, the sister of the Emperor Maximilian, and through her influence to the emperor himself. On 19 August 1509, Maximilian, who already had expelled the Jews from his own domains of Styria, Carinthia, and Carniola,[1] ordered the Jews to deliver to Pfefferkorn all books opposing Christianity;[3] or the destruction of any Hebrew book except the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament).[1] Pfefferkorn began the work of confiscation at Frankfort-on-the-Main,[3] or possibly Magdeburg;[4] thence he went to Worms, Mainz, Bingen, Lorch, Lahnstein, and Deutz.[3]

Through the help of the Elector and Archbishop of Mainz, Uriel von Gemmingen, the Jews asked the emperor to appoint a commission to investigate Pfefferkorn's accusations.[4] A new imperial mandate of 10 November 1509, gave the direction of the whole affair to Uriel von Gemmingen, with orders to secure opinions from the Universities of Mainz, Cologne, Erfurt, and Heidelberg, from the inquisitor Jacob van Hoogstraaten of Cologne, from the priest (and former rabbi) Victor von Carben, and from Johann Reuchlin.[3] Pfefferkorn, in order to vindicate his action and to gain still further the good will of the emperor, wrote In Lob und Eer dem allerdurchleuchtigsten grossmechtigsten Fürsten und Herrn Maximilian (Cologne, 1510).[3] In April he was again at Frankfort, and with the delegate of the Elector of Mainz and Professor Hermann Ortlieb, he undertook a new confiscation.[3]

Van Hoogstraaten and the Universities of Mainz and Cologne decided in October 1510 against the Jewish books.[3] Reuchlin declared that only those books obviously offensive (as the Nizachon and Toldoth Jeschu) would be destroyed.[3] The elector sent all the answers received at the end of October to the emperor through Pfefferkorn.[3] Reuchlin reported in favor of the Jews; on 23 May 1510 the emperor suspended his edict of 10 November 1509 and the books were returned to the Jews on 6 June.[1]

Battle of pamphlets

The ensuing battle of pamphlets between Pfefferkorn and Reuchlin reflected the struggle between the Dominicans and the humanists.[4] Thus informed of Reuchlin's vote Pfefferkorn was greatly excited, and answered with Handspiegel (Mainz, 1511), in which he attacked Reuchlin unmercifully.[3] Reuchlin complained to Emperor Maximilian, and answered Pfefferkorn's attack with his Augenspiegel, against which Pfefferkorn published his Brandspiegel.[3] In June 1513, both parties were silenced by the emperor.[3] Pfefferkorn however published in 1514 a new polemic, Sturmglock, against both the Jews and Reuchlin.[3] During the controversy between Reuchlin and the theologians of Cologne, Pfefferkorn was assailed in the Epistolæ obscurorum virorum by the young Humanists who espoused Reuchlin's cause.[3] He replied with Beschirmung, or Defensio J. Pepericorni contra famosas et criminales obscurorum virorum epistolas (Cologne, 1516), Streitbüchlein (1517).[3] In 1520, Pope Leo X declared Reuchlin guilty with a condemnation of Augenspiegel, and Pfefferkorn wrote as an expression of his triumph Ein mitleidliche Klag (Cologne, 1521).[3] Diarmaid MacCulloch writes in his book The Reformation: A History (2003)[5] that Desiderius Erasmus was another opponent of Pfefferkorn, on the grounds that he was a converted Jew and therefore could not be trusted.

Works

- Der Judenspiegel (Speculum Adhortationis Judaicæ ad Christum), Nuremberg, 1507

- Der Warnungsspiegel (The Mirror of Warning), year?

- Die Judenbeicht (Libellus de Judaica Confessione sive Sabbate Afflictionis cum Figuris), Cologne, 1508

- Das Osterbuch (Narratio de Ratione Pascha Celebrandi Inter Judæos Recepta), Cologne and Augsburg, 1509

- Der Judenfeind (Hostis Judæorum), ib. 1509

- In Lib und Ehren dem Kaiser Maximilian (In Laudem et Honorem Illustrissimi Imperatoris Maximiliani), Cologne, 1510

- Handspiegel (Mayence, 1511)

- Der Brandspiegel (Cologne, 1513)

- Die Sturmglocke (ib. 1514)

- Streitbüchlein Wider Reuchlin und Seine Jünger (Defensio Contra Famosas et Criminales Obscurorum Virorum Epistolas (Cologne, 1516)

- Eine Mitleidige Clag Gegen den Ungläubigen Reuchlin (1521)

See also

- Anton Margaritha

- Johann Eisenmenger

- Martin Luther

- Samuel Friedrich Brenz

- Nicholas Donin

- Jacob Brafman

- Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

Reference Notes

- ^ a b c d Deutsch, Gotthard; Frederick T. Haneman. "Pfefferkorn, Johann (Joseph)". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Carlebach, Elisheva (2001). Divided Souls: Converts from Judaism in Germany, 1500-1750. Yale University Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-300-08410-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Johannes Pfefferkorn". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Reuchlin, Pfefferkorn, and the Talmud in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries in The Babylonian Talmud. The History of the Talmud translated by Michael L. Rodkinson. Book 10 Vol. I Chapter XIV (1918), p. 76.

- ^ Diarmaid MacCulloch: Reformation: A History. New York: Penguin Books Ltd. (2004) p. 665

External links

- Jewish Encyclopedia: "Pfefferkorn, Johann (Joseph)" by Gotthard Deutsch & Frederick Haneman (1906). Now in public domain.

- Lauchert, Friedrich (1911). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11.

- Reuchlin, Pfefferkorn, and the Talmud in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries at sacred-texts.com

- Reuchlin at Christian Classics Ethereal Library at Calvin College

- Minorities in the Imperial Tradition

- Video Lecture on Johannes Pfefferkorn by Dr. Henry Abramson of Touro College South