Perry Owens

Commodore Perry Owens (July 29, 1852 – May 10, 1919) was an American lawman and gunfighter of the Old West. One of his many exploits was the Owens-Blevins Shootout in Arizona Territory during the Pleasant Valley War.

Early life

Commodore Perry Owens was born July 29, 1852, not on September 10 as asserted by some sources. His father was named Oliver H. Perry Owens after Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, a United States Naval hero of the War of 1812. Commodore was named by his mother. He was born in Hawkins County, Tennessee; his family migrated and developed a farm in Liberty Township, Hendricks County, Indiana. At age 13, Commodore ran away from home and went West, where he was eventually hired on as a buffalo hunter for the railroad. Killing buffalo each day to feed the railroad workers, Owens became an incredible shot. He was able to shoot a rifle accurately from the hip, without using the sights. Owens was ambidextrous and wore two pistols. He would entertain friends by shooting a can across the pasture with alternating shots from his left and right hands. Owens later worked on the ranches of Oklahoma and New Mexico as a cowboy.

Owens is known to have been working on Hillard Roger's ranch outside Bartlesville, Oklahoma on his twenty-first birthday. In an interview given later in life, Owens admitted running with a "gang of tough characters" in his youth and was possibly involved in rustling, whiskey running and other depredations in the Indian Territory.[1][2]

Arizona Territory

By 1881, Owens at age 28 was working as a ranch foreman for James D. Houck and A. E. Hennings in Navajo Springs, Arizona, northeast of present-day Holbrook, Arizona. Myths have arisen about Owens' dealings with the Navajo in the area during this period. It was their traditional territory, and they resisted American encroachment. In one incident, when attacked by Navajo locals trying to steal horses under his watch, Owens allegedly killed at least two warriors, and earned the nickname "Iron Man".

In September 1883, Owens was arrested by U.S. Indian Agent Denis Matthew Riordan, for the murder of a young Navajo boy near Houck's ranch. Owens shot and killed the youth, who, he said, was trying to rustle horses. Owens was tried and subsequently acquitted of the murder by an Apache County jury.[citation needed]

Owens had red hair and dressed as a typical cowboy, as seen in his photo taken in New Mexico. He wore his hair long in his youth, often curling it up underneath his hat, was popular with the ladies, and was often teased because of his unusual name. Around this time, he homesteaded outside Navajo Springs, building a small dugout/cabin, well, and stables for his livestock near the stage station. He raised purebred horses. Owens is said to have named his place the "Z-Bar Ranch", but this brand was not officially registered with the Apache County Recorder's Office.[1]

Lawman, gunfighter

Owens established a reputation as a gunfighter and was nominated by the People's Party for Sheriff of Apache County, Arizona. He had the support of the Apache County Stockgrowers Association, and the Mormons and Mexicans also supported him. Owens won the Sheriff's office in November 1886. (Apache County was split into two counties in 1895, with the western part becoming Navajo County). He was responsible for 21,177 square miles (54,850 km2) of territory – more than the combined area of New Hampshire and Vermont. Elected by a margin of 91 votes over Democratic candidate Tomas Perez, Owens was well-liked within his jurisdiction. A newspaper said, "Mr. Owens is a quiet, unassuming man, strictly honorable and upright in his dealings with all men and is immensely popular."

Upon taking office in January 1887, Owens was entrusted with 14 bench warrants that had been left unserved by his predecessor, Jon "Don" Lorenzo Hubbell. Included among these were warrants for the Mormon gunman Lot Smith, former Tombstone badman Ike Clanton, and rustler "Andrew Arnold Cooper," an alias for Andy Blevins. The Clanton Gang and Blevins Brothers both had notorious reputations in Arizona as rustlers and outlaws. Citizens of Apache County expected the new sheriff to take action against the two gangs. Sheriff Owens immediately cleaned up the filthy jail and accounted for public funds down to the postage stamps he used.

- Ike Clanton's Death

Newman Haynes Clanton, known as Old Man Clanton, his sons, and his "cowboys" were a loose gang of rustlers and smugglers. Clanton's ranch near Tombstone was used to hide stolen cattle, rebrand them, then sell them. Old Man Clanton was killed on August 13, 1881 in the Guadalupe Canyon Massacre when Mexican troops attacked cattle smugglers near the Mexican border. Ike Clanton and his family had been longtime adversaries of the Earp brothers and Clanton had threatened to kill the Earps. On October 26, 1881 Ike Clanton's threats instigated the Gunfight at the OK Corral. Ike fled as the shooting started, while his younger brother Billy Clanton died in the shootout. In December 1881 someone ambushed Virgil Earp with a shotgun, maiming him. Ike's hat was found behind the building where the shot had been fired. Ike was arrested for shooting Virgil Earp, but the charges were dismissed for lack of evidence when his friends testified he'd been out of town. Three months later Morgan Earp was killed in an ambush. Wyatt Earp formed a posse, searched for Ike Clanton and killed four of the "cowboys", but never found Clanton. Clanton moved north, away from Tombstone, to Apache County, east of Springerville. Clanton was well-to-do, having said that ranching was 'very profitable when you didn't have to buy the cows.'

The Clanton gang now wreaked havoc in Apache County. On November 6, 1886 rancher Isaac Ellinger was shot at Clanton's ranch by gang member Lee Renfo. Ellinger and a witness said it was entirely unprovoked, and Ellinger died four days later. On Christmas Day 1886 another Clanton Gang member, Billy Evans, wanted to 'see if a bullet would go through a Mormon' and killed Jim Hale (who had identified cattle stolen by the Clantons) in cold blood. When Owens became sheriff at the first of the year he hired ex-Texas lawman Jeff Milton to arrest the Clantons, but Milton later backed out. In May 1886 the Apache County grand jury again indicted Ike Clanton and other gang members. Sheriff Owens had deputies Rawhide Jake Brighton and Albert Miller go to arrest Ike Clanton and his associates (Brighton was also Springerville Constable and a range detective or "secret service officer" hired by the cattlemen's association). Clanton was not at his ranch but the deputies ran into Ike Clanton on June 1, 1887. Ike Clanton was on his horse, pulled his Winchester from its scabbard, and turned his horse toward a stand of trees. Brighton shot, hitting Clanton's saddle horn. Brighton's second shot killed Ike Clanton. Some sources say that Ike's brother Phin (sometimes spelled "Fin") Clanton was with Ike at his death and was arrested. Other sources say Phin was arrested earlier and in the St. Johns jail at the time. In July, gang members Billy Evans and Longhair Sprague were killed when ranchers trailing stolen horses returned the rustler's gunfire. Soon after gang member Lee Renfo was killed by Rawhide Jake Brighton when Renfo went for his gun as Brighton tried to arrest him. The Clanton rustlers were at an end.

- The Holbrook Shootout

Andy Blevins was a native of Mason County Texas, west of Austin. Blevin came to Arizona in 1885 with his brother Charlie Blevins, in order to escape arrest for crimes he had purportedly committed in Texas, including murder. Andy Blevins changed his name to Cooper to avoid arrest. The Blevins brothers were eventually joined by younger brothers, their mother, and relations – the remainder of the Blevins clan. Andy Blevins was known to have killed three Navajo men and was suspected of rustling a herd of horses from the Navajo reservation. There were rumors he had killed two lawmen who were tracking him. Cooper's half-brothers from the Blevins family, including John Black and William "Hamp" Hampton, were also suspected cattle rustlers.

During this period, a range war had erupted in neighboring Yavapai County between the Graham and Tewksbury families, which would become known as the Pleasant Valley War. Cooper and the other Blevins brothers became allies of the Graham family, who were known as cattlemen. They were feuding with the Tewksbury family, who had herds of sheep by 1885 but had originally also been cattle ranchers. The Tewksbury family was part Indian, and historians have thought that racial prejudice was also part of the feuding. Though the feud occasionally spilled over into his county, Owens seems to have remained neutral.[1][3]

Old Man Blevins disappeared in June 1887 and was thought to have been killed by the Tewksbury faction or by Apaches. The Blevins brothers searched for their father with help from some Hashknife Cowboys and in one of the forays Hamp Blevins and another were killed by the Tewksbury side. They had gone to a ranch formerly owned by the Middleton Family where a family friend of the Tewksbury's lived. There, a confrontation broke out and resulted in the Blevins' retreat. On September 2, 1887 Andy Blevins and others ambushed and killed John Tewksbury and Bill Jacobs in revenge. Blevins returned to Holbrook and was heard bragging about the killings.

Sheriff Owens had inherited an old warrant for Andy Cooper (Blevins) arrest, but had never gone after Blevins. Some said it was because Owens and Blevins were friends, having been cowboys together. Others said Owens was afraid of Blevins, who was known as a fine shot and a cold killer. The warrant was for the theft of some twenty-five horses from a Mormon, who had tracked his horses to the Blevins Canyon Creek Ranch and identified Andy. A county official had likewise seen Andy driving the horses.

On Sunday, September 4, 1887, Sheriff Owens heard Andy was in Holbrook and rode to the Blevins' cottage in Holbrook to serve the outstanding warrant for rustling on Andy Blevins/Cooper. Twelve people were inside the house that afternoon when Owens reached it, including Cooper (the eldest Blevins brother), the younger brothers John and Sam Houston Blevins; the brothers' mother, Mrs. Blevins; John Blevins' wife Eva and their infant son; a family friend, Miss Amanda Gladden; house guest Mose Roberts; and several children.

Cradling his Winchester rifle in his arm, Sheriff Owens knocked on the door and, when Andy Blevins answered with a pistol in hand, the lawman told him to come out of the house, stating that he had a warrant for arrest. Blevins refused to comply and tried to close the door. Owens dropped the rifle to his hip and shot Blevins through the door, hitting him in the abdomen. Andy's half-brother, John Blevins, pushed a pistol out the door to Owens' right and fired a shot at the Sheriff. He missed and killed Andy's saddle horse, which was tied to a tree. Owens turned toward his assailant and fired, wounding John Blevins in the arm, and putting him out of the fight.

Owens backed away into the yard so he could see three sides of the house. Seeing Andy Blevins moving inside, Owens fired a third time through the front wall of the cottage, striking Andy in the right hip. Mose Roberts, boarding with the family, jumped out of a side window. Roberts saw the Sheriff and immediately turned to run. Owens shot him, the bullet passing through his back and out of his chest. Roberts stumbled around the back of the house and fell at the back door. Arizona Sketchbook author Frank Brophy and others have alleged that Roberts was unarmed, and that he jumped from the window to avoid Owens' third shot, which entered the house, but the coroner's jury report indicated that a blood-covered pistol was found near the back door of the cottage where Roberts had re-entered the house after being shot. The doctor who treated Roberts testified that a pistol was there when he attended to Roberts.

After Owens shot Roberts, fifteen-year-old Samuel Houston Blevins ran out the front door, gripping his brother Andy's Colt revolver, which he had taken from the mortally wounded outlaw. The younger brother yelled, "I'll get him." His mother tried to hold him back, but Sam broke loose. As the youth came toward him, Owens shot and killed him. Sam fell backward, dying in his mother's arms. The whole incident took less than one minute and the shootout made Owens a legend.[4]

Locally, Owens was praised for ridding the county of Andy Cooper, a notorious outlaw. Three separate coroner's juries, called for each of the deaths, found Owens' actions justifiable. The Gunfight at Holbrook was lauded in most circles, but Owens' lack of formal education became a liability. As Apache County became more developed, the constituency began to wonder if Owens had the skills to be as good an administrator as he was a fighter.

Additionally, Owens had problems retaining his bonds and his sureties. Owens would have "twenty-three different citizens underwriting his honesty and effectiveness in office." The outlaws Robert W. "Red" McNeil and Grant S. "Kid" Swingle continued to escape his attempts to capture them. Owens was criticized for holding John Blevins in custody, although he was pardoned by the governor for shooting at the sheriff during the conflict at his house. Commodore Perry Owens finished out his term as Apache County Sheriff, but he was defeated in the election of November 1888 by his former deputy, St. George Creaghe. On January 1, Owens left the sheriff's office.[5]

Later life

In the fall of 1892 Owens again sought nomination for the office of Apache County Sheriff, this time on the Democratic ticket. He lost to Joseph Woods, who was defeated in the election by Republican W. R. Campbell. Owens went to work for Campbell as his Chief Deputy. In 1894, Owens ran again for sheriff, securing the Democratic nomination, but he was defeated by the Republican candidate by a margin of 50 votes.

In August 1893, Owens was appointed to the position of Deputy U.S. Marshal under William Kidder Meade. In 1895 he was appointed as Sheriff of the newly created Navajo County by Governor Louis Cameron Hughes, serving two years. Owens appointed as his Under Sheriff his nephew Robert Hufford, son of his sister Mary Francis. These later years did not have the high drama of his days as Apache County Sheriff, but Owens was still considered a formidable opponent by outlaws.

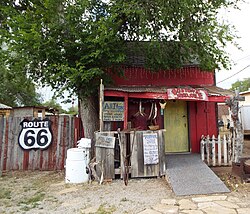

After his term as Sheriff of Navajo County expired, Owens did not seek reelection. He retired to Seligman, Arizona, where he bought property and opened a general store and a saloon. While the other buildings have long since been torn down, Owen's house still stands. Owens later claimed in interviews to have killed 14 men during his career, but this claim cannot be substantiated.[1]

In 1902 Owens married a woman named Elizabeth Jane Barrett. The couple had no children. The census of 1910 shows Owens and his wife were residing in San Diego, California. Owens eventually returned to Seligman. On February 14, 1912 the Arizona territory become the 48th state in the Union.

In the end, Owens succumbed to Bright's disease (or possible paresis of the brain) and died on May 28, 1919, aged 67. He left his wife an estate totaling over $10,000.[6] Owens was buried in Citizens Cemetery in Flagstaff, Arizona.[7]

Elizabeth Jane Owens survived her husband by 21 years, dying in San Diego on April 30, 1945.[1]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e "Commodore Perry Owens", Arizona Journal Archived April 22, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Arizona Republican, February 14, 1898

- ^ "Pleasant Valley History", at youngaz85554.tripod.com [dead link]

- ^ Coroner' Inquests into the Deaths of Samuel Houston Blevins, Mose Roberts, and Andrew Cooper. All documents available at the Arizona State Library and Archives in Phoenix, Arizona.

- ^ Leland J. Hanchett Jr., The Crooked Trail to Holbrook (1993)

- ^ "Last Will and Testament of Commodore Perry Owens," held at Arizona State Library, Archives, and Public Records

- ^ "Commodore Perry Owens". arizonagravestones.org. Gravestone Photo Project (GPP).

Further reading

- Larry D. Ball, "Commodore Perry Owens: The Man Behind the Legend," The Journal of Arizona History, Spring 1992

- Will C. Barnes, Apaches and Longhorns

- Will C. Barnes, Gunfight in Apache County (ed. Neil Carmony)

- Robert Carlock, The Hashknife: The Early Days of The Aztec Land and Cattle Company

- Don Dedra, A Little War of Our Own

- Earle Forrest, Arizona's Dark and Bloody Ground

- David Grasse, Commodore Perry Owens: The Life of an Arizona Lawman (an excerpt), (2006 Arizona Historical Convention Paper)

- Herman, Daniel J. (April 2012), "Arizona's Secret History: When Powerful Mormons Went Separate Ways", Common-place, 12 (3)