Perpendicular Gothic

Perpendicular Gothic (also Perpendicular, Rectilinear, or Third Pointed) architecture was the third and final style of English Gothic architecture developed in the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ages, typified by large windows, four-centred arches, straight vertical and horizontal lines in the tracery, and regular arch-topped rectangular panelling.[1][2] Perpendicular was the prevailing style of Late Gothic architecture in England from the 14th century to the 17th century.[1][2] Perpendicular was unique to the country: no equivalent arose in Continental Europe or elsewhere in the British-Irish Isles.[1] Of all the Gothic architectural styles, Perpendicular was the first to experience a second wave of popularity from the 18th century on in Gothic Revival architecture.[1]

The pointed arches used in Perpendicular were often four-centred arches, allowing them to be rather wider and flatter than in other Gothic styles.[1] Perpendicular tracery is characterized by mullions that rise vertically as far as the soffit of the window, with horizontal transoms frequently decorated with miniature crenellations.[1] Blind panels covering the walls continued the strong straight lines of verticals and horizontals established by the tracery. Together with flattened arches and roofs, crenellations, hood mouldings, lierne vaulting, and fan vaulting were the typical stylistic features.[1]

The first Perpendicular style building was designed in c. 1332 by William de Ramsey: a chapter house for Old St Paul's Cathedral, the cathedral of the bishop of London.[1] The chancel of Gloucester Cathedral (c. 1337–1357) and its latter 14th-century cloisters are early examples.[1] Four-centred arches were often used, and lierne vaults seen in early buildings were developed into fan vaults, first at the latter 14th-century chapter house of Hereford Cathedral (demolished 1769) and cloisters at Gloucester, and then at Reginald Ely's King's College Chapel, Cambridge (1446–1461) and the brothers William and Robert Vertue's Henry VII Chapel (c. 1503–1512) at Westminster Abbey.[1][3][4]

The architect and art historian Thomas Rickman's Attempt to Discriminate the Style of Architecture in England, first published in 1812, divided Gothic architecture in the British Isles into three stylistic periods.[5] The third and final style – Perpendicular – Rickman characterised as mostly belonging to buildings built from the reign of Richard II (r. 1377–1399) to that of Henry VIII (r. 1509–1547).[5] From the 15th century, under the House of Tudor, the prevailing Perpendicular style is commonly known as Tudor architecture, being ultimately succeeded by Elizabethan architecture and Renaissance architecture under Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603).[6] Rickman had excluded from his scheme most new buildings after Henry VIII's reign, calling the style of "additions and rebuilding" in the later 16th and earlier 17th centuries "often much debased".[5]

Perpendicular followed the Decorated Gothic (or Second Pointed) style and preceded the arrival of Renaissance elements in Tudor and Elizabethan architecture.[7] As a Late Gothic style contemporary with Flamboyant in France and elsewhere in Europe, the heyday of Perpendicular is traditionally dated from 1377 until 1547, or from the beginning of the reign of Richard II to the beginning the reign of Edward VI.[8] Though the style rarely appeared on the European continent, it was dominant in England until the mid-16th century.[9]

History

In 1906 William Lethaby, Surveyor of the Fabric of Westminster Abbey, proposed that the origin of the Perpendicular style was to be found not in 14th-century Gloucester, as was traditionally argued, but in London, where the court of the House of Plantagenet was based at Westminster Palace beside Westminster Abbey.[10] The cathedral of London, the episcopal see of the third-most senior bishop in the Church of England, was then Old St Paul's Cathedral. According to the architectural historian John Harvey, the octagonal chapter house of St Paul's, built about 1332 by William Ramsey for the cathedral canons, was the earliest example of Perpendicular Gothic.[11][12] Alec Clifton-Taylor agreed that St Paul's chapter house and St Stephen's Chapel at Westminster Palace predate the early Perpendicular work at Gloucester.[13] In the early 21st century the outline of the foundations of the chapter house was made visible in the redeveloped south churchyard of the present 17th-century cathedral.[14]

The chapter house at St Paul's was built under the direction of William de Ramsey, who had worked on earlier phases of the still-unfinished St Stephens's Chapel. Ramsey extended the stone mullions of the windows downwards on the walls. At the top of each window he made a four-centred arch which became a distinctive feature of Perpendicular.[11][9] Along with rest of Old St Paul's, the chapter house was destroyed by the Great Fire of London in 1666.

Elements of early Perpendicular are also known from St Stephen's Chapel at Westminster Palace, a palatine chapel built by King Edward I following the model of Sainte-Chapelle at the Palais de la Cité in medieval Paris.[11] It was built in phases over a long period, from 1292 until 1348, though today only the crypt exists. The architect of the early building was Michael of Canterbury, followed in 1323 by his son Thomas. One of the original decorative features was a kind of blind tracery; blank vertical panels with cusped, or angular tops in the interior; and, on the exterior, thin stone mullions or ribs extending downward below the windows creating perpendicular spaces. These became the most characteristic feature of the style.[9]

The earliest Perpendicular in a major church is the choir of Gloucester Cathedral (1337–1350) constructed when the south transept and choir of the then Benedictine abbey church (Gloucester was not a bishopric until after the Dissolution of the Monasteries) were rebuilt in 1331–1350. It was likely the work of one of the royal architects, either William de Ramsey, who had worked on the London cathedral chapter house, or Thomas of Canterbury, who was architect to the king when the transept of Gloucester Cathedral was begun. The architect preserved the original 11th-century walls, covering them with Flamboyant mullions and panels. The east window of Gloucester choir has a Tudor arch, filling the wall with glass. The window tracery matches the tracery on the walls.[15]

During the reign of Edward III the style began to dominate at the Court, especially at the redevelopment of Windsor Castle, where John Sponlee designed the buildings to house Edward's neo-Arthurian fancies. Of these the Dean's Cloister and Aerary Porch survive and exhibit early Perpendicular blind tracery and lierne vaults.[16]

The style attained maturity under Henry Yevele and William Wynford in the later 14th century. Yevele designed works for the King and Court, such as Westminster Hall, Portchester Castle and the naves of Westminster Abbey and Canterbury Cathedral, while Wynford predominantly worked for Bishop Wykeham of Winchester on the nave of the cathedral itself as well as his educational foundations of New College, Oxford and Winchester College.[17] By c.1400 the style was widespread across the country, from Melrose in Scotland to Wells in Somerset.

Under the pious Henry VI the official style of the Court became relatively austere, as seen at the chapels of King's College, Cambridge and Eton College.[18] However, the original intentions at both buildings are now obscured as the building work continued long after the King was overthrown, with design changes resulting in increasing ornamentation. The same process occurred at the Divinity School, Oxford.

In the later 15th century, the pendulum swung back towards elaboration, especially under the Tudors. John Harvey considered this change to be significant enough to merit Tudor Gothic being considered as a separate style,[19] with greater continental influence, but this position is not widely held. At this period many of the most dazzling vaults were constructed, such as those by John Wastell at Peterborough Abbey (now a cathedral) and King's College chapel. These were both straightforward fan vaults, but pendant vaulting also reached its apogee with those over St Frideswide's Priory (now Oxford Cathedral) and the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey, a major example of the late Perpendicular style. Another important example is St George's Chapel at Windsor Castle, begun in 1475. The vault of the chapel was contracted to the master-mason John Aylmer in 1506.[20]

Characteristics

- Towers were exceptionally tall, and frequently had battlements. Spires were less frequent than in earlier periods. Buttresses were often placed at the corners of the tower, the best position for providing maximum support. Notable Perpendicular towers include those of York Minster and Gloucester Cathedral, and the churches of Boston (Lincolnshire)[clarification needed], Wrexham and Taunton.[21]

- Stained glass windows were so large that the walls between were reduced to little more than piers. Horizontal mullions, called "transoms", often had to be added to the windows to give them greater stability.[22]

- Tracery was a major feature of decoration. In the larger churches, the entire surface from ground to summit, including the battlements, was covered with panels of tracery composed of thin stone mullions. It also appeared frequently in the interior, and often carried the designs in the window tracery down to the floor.[21] Tracery designs were less varied, with three main types: angular reticulation, common in the west of England, panel tracery, seen in the east, and the Court style, characterised by sub-arches filled with inverted daggers in the side lights.[23]

- Roofs were frequently made of lead, and usually had a gentle slope, to make them easier for walking[citation needed]. The roof timbers on the interior were often exposed to view from below, and had ornamental supports.[21] In this period the hammerbeam roof was used over select high-status buildings.

- Vaults of stone were frequently elaborate and highly decorative. The most common types on major buildings were fan vaults and lierne vaults, both of which could be further elaborated with pendants. The increased weight of the vaults caused by the ornament was countered by larger buttresses on the exterior.[21]

- Columns were generally octagonal in section, with octagonal bases and capitals. In greater churches shafting was commonplace, and could be carried up above the capitals to unify the elevation vertically. The capitals were usually decorated with moulded or carved oak leaves, or with corbels of shields or armorial symbols, or with the Tudor rose.[24] In more advanced buildings, capitals became less prominent.

- Fourth-centred arches or Tudor arches were commonly used in windows and tracery and for vaults and doorways, though the two-centred arch dominated until late in the period.

- The interiors had richly carved woodwork, particularly in the choir stalls, which often featured carved grotesque figures on the bench ends called "poppy heads", from French: poupée, lit. 'doll'. [24] Pulpits and benches became more common in churches with the increased emphasis on preaching. Chantry chapels appeared in major churches, either as screened-off sections or structural editions, paid for by wealthy individuals or guilds.

Examples

- Palace of Westminster, St Stephen's Chapel (largely destroyed), Westminster Hall

- Old St Paul's, London, Chapter House (destroyed)

- Gloucester Cathedral, recasing of transepts, choir and presbytery, cloister, tower, Lady Chapel, west front

- Hereford Cathedral, Chapter House (destroyed)

- Windsor Castle, Dean's Cloister, St George's Chapel

- Westminster Abbey, cloister (heavily restored), nave, Henry VI's Chantry, Henry VII's Chapel

- Winchester Cathedral, west front, recasing of nave, choir

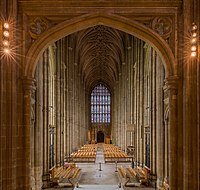

- Canterbury Cathedral, nave, cloister, remodelling of Chapter House, south-west tower, Bell Harry Tower, Christ Church Gate

- New College, Oxford

- Winchester College

- King's College, Cambridge, Chapel

- Eton College

- Maidstone College

- Norwich Cathedral, cloister, choir clerestory, vaults, spire

- York Minster, retrochoir, choir, towers

- Durham Cathedral, central tower

- Tattershall, Castle tower and collegiate church

- Coventry Cathedral (formerly St Michael's Church, now in ruins)

- Magdalen College, Oxford

- Christ Church, Oxford, vault of cathedral, Tom Quad (never fully completed)

- St Mary's Church, Warwick, choir and Beaufort Chapel

- Peterborough Cathedral, New Building (retrochoir)

- Great Malvern Priory, everything except the nave arcades

- Melrose Abbey, presbytery

- Lavenham Church

- Long Melford Church

- Bath Abbey

- Manchester Cathedral

- South Wingfield Manor

- Hampton Court Palace (with some early Renaissance influence)

Gallery

- Winchester Cathedral west front

- Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey (1503–), with Perpendicular tracery and blind panels.

- Edington Priory west front: Decorated and Perpendicular

- Beauchamp Chapel, Collegiate Church of St Mary, Warwick

- Manchester Cathedral chancel

- Hall of Christ Church, Oxford

- Hull Minster nave

- Merton College Chapel tower

- Gloucester Cathedral, choir and chancel

- Bath Abbey chancel

- York Minster chancel, looking west

- Canterbury Cathedral nave

- Winchester Cathedral nave

- York Minster crossing tower

- Evesham Abbey bell tower

- Bridlington Priory west front

- Gloucester Cathedral east end (1331–1350), with a four-centred arch window

- Canterbury Cathedral crossing tower and transepts

- Wells Cathedral crossing tower

- Beverley Minster west front

- Norwich Cathedral spire and west window

- Chichester Cathedral spire

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan, eds. (2015), "Perpendicular", A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199674985.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5, retrieved 2020-05-16

- ^ a b Fraser, Murray, ed. (2018), "Perpendicular Gothic", Sir Banister Fletcher Glossary, Royal Institute of British Architects and the University of London, doi:10.5040/9781350122741.1001816, ISBN 978-1-350-12274-1, retrieved 2020-08-26,

English idiom from about 1330 to 1640, characterised by large windows, regularity of ornate detailing, and grids of panelling that extend over walls, windows and vaults.

- ^ Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan, eds. (2015), "Ely, Reginald", A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199674985.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5, retrieved 2020-05-16

- ^ Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan, eds. (2015), "Vertue, Robert", A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199674985.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5, retrieved 2020-05-16

- ^ a b c Rickman, Thomas (1848) [1812]. An Attempt to Discriminate the Styles of Architecture in England: From the Conquest to the Reformation (5th ed.). London: J. H. Parker. pp. lxiii.

- ^ Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan, eds. (2015), "Tudor", A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199674985.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5, retrieved 2020-04-09

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica on-line, "Perpendicular Gothic", retrieved August 19, 2020

- ^ Smith 1922, p. loc. 204.

- ^ a b c Watkin 1986, p. 152.

- ^ Lethaby, William Richard (1906). Westminster Abbey & the King's Craftsmen: A Study of Mediæval Building. E. P. Dutton. ISBN 978-0-405-08745-5.

- ^ a b c Harvey, John H. (1946). "St. Stephen's Chapel and the Origin of the Perpendicular Style". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 88 (521): 192–199. ISSN 0951-0788. JSTOR 869300.

- ^ Harvey, John Hooper (1978). The Perpendicular Style, 1330-1485. London: Batsford. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-7134-1610-7.

- ^ Clifton-Taylor, Alec (1967). The Cathedrals of England. World of Art. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 196. ISBN 0-500-20062-9. OCLC 2631377.

- ^ Peterkin, Tom (2008-06-04). "St Paul's Cathedral opens new South Churchyard". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 2020-08-28.

- ^ Watkin 1986, p. 153.

- ^ Harvey, John (1978). The Perpendicular Style. London: Batsford. p. 84. ISBN 0-7134-1610-6.

- ^ Harvey, John (1978). The Perpendicular Style. London: Batsford. pp. 97–136. ISBN 0-7134-1610-6.

- ^ Harvey, John (1978). The Perpendicular Style. London: Batsford. pp. 185–186. ISBN 0-7134-1610-6.

- ^ Harvey, John (1978). The Perpendicular Style. London: Batsford. p. 13. ISBN 0-7134-1610-6.

- ^ Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan, eds. (2015), "Aylmer, John", A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199674985.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-967498-5, retrieved 2020-05-16

- ^ a b c d Smith 1922, 335.

- ^ Smith 1922, 327.

- ^ Harvey, John (1978). The Perpendicular Style. London: Batsford. pp. 63, 71, 153. ISBN 0-7134-1610-6.

- ^ a b Smith 1922, 352.

Bibliography

- Bechmann, Roland (2017). Les Racines des Cathédrals (in French). Paris: Payot. ISBN 978-2-228-90651-7.

- Ducher, Robert, Caractéristique des Styles, (1988), Flammarion, Paris (in French); ISBN 2-08-011539-1

- Harvey, John (1961). English Cathedrals. Batsford. OCLC 2437034.

- Smith, A. Freeman (1922). English Church Architecture of the Middle Ages – an Elementary Handbook. T. Fisher Unwin.

- Martin, G. H.; Highfield, J. R. L. (1997). A history of Merton College, Oxford. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-920183-8.

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.