Pelanomodon

| Pelanomodon Temporal range: Late Permian, | |

|---|---|

| |

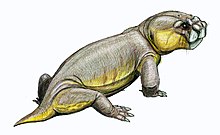

| Restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Anomodontia |

| Clade: | †Dicynodontia |

| Family: | †Geikiidae |

| Genus: | †Pelanomodon Broom, 1938 |

| Type species | |

| †P. moschops (Broom, 1913) (originally Dicynodon moschops) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Pelanomodon is an extinct genus of dicynodont therapsids that lived in the Late Permian period. Fossil evidence of this genus is principally found in the Karoo Basin of South Africa, in the Dicynodon Assemblage Zone.[1] Lack of fossil record after the Late Permian epoch suggests that Pelanomodon fell victim to the Permian-Triassic extinction event.

The name Pelanomodon can be broken up into three parts; “pelos” meaning mud, “anomo” meaning irregular and “odon” meaning tooth. Together, this suggests Pelanomodon to be a mud dwelling anomodont (a group of therapsids that are characterized by their lack of teeth).[2] The Karoo Basin during this period was characterized by its extensive flood plains,[3] so to hypothesize a mud based habitat for this genus is not far fetched.

Pelanomodon is in the family Geikiidae along with Aulacephalodon and Geikia. Aulacephalodon is believed to have lived alongside Pelanomodon in the Karoo Basin, where as records of Geikia have been discovered in Scotland and Tanzania. Pelanomodon is primarily characterized and distinguished from Aulacephalodon by its lack of tusks.[1] Other cranial features have been used by paleontologists to establish two species of Pelanomodon; P. moschops and P. rubidgei. However, recent analysis points to the conclusion that these may in fact the same species.[1]

Description

Skull

The fossil record of Pelanomodon is principally made up of both complete and partial skulls. It is for this reason that morphology of the skull is used to distinguish Pelanomodon from other genus in the Geikiines family. The absence of tusks is a significant feature that is used to differentiate Pelanomodon from Aulacephalodon, in addition to bosses on the post orbital bar and twisting of the zygoma.[1] Pelanomodon is distinguished from Geikia due to its longer temporal fenestra and snout, lesser developed oesophageal crest and flush pineal foramen.[1]

In addition to these distinctions, Pelanomodon's skull has many other characteristic features. One of the most apparent of these features being that its skull is wider than it is tall, resulting in a triangular shape, when viewed dorsally.[1] In connection with this, the temporal fenestra angle out posterolaterally.[1] Compared to other dicynodonts, the external naris is retracted and located relatively high on the snout.[1] Likewise, the orbits are also placed higher than is typically seen in dicynodonts.[1] In accordance with other Anomodonts, Pelanomodon have cheek teeth but lack their molar teeth.[2] In addition, like other therapsids, the premaxilla extends on the ventral side in order to form a secondary palate.[1]

Discovery and naming

Pelanomodon was first discovered by Robert Broom, in the Karoo Basin of South Africa, in 1913. Its classification was based on a nearly complete skull, missing only the lower jaw.[4] The species was originally named Dicynodon moschops, however, in 1969 an analysis done by A. W. Keyser reclassified the specimen as Pelanomodon moschops.[5] Another species, Pelanomodon rubidgei, was classified by Broom in 1938, and was established from a complete skull found in the same region, by S. H Rubidge.[6]

Between the years of 1913 and 1950, Broom described five different Pelanomodon species, based on differences observed between many partial, and complete skulls.[4][6][7][8] However, since this time, several paleontologists have re-evaluated the morphology of the skulls and reclassified them all as either Pelanomodon rubidgei or Pelanomodon moschops.[5][9] Since fossil records can never provide a complete understanding of the past, these classifications are still debated among paleontologists.

In 2016, a new analysis suggested that the morphological features used to distinguish between Pelanomodon moschops and Pelanomodon rubidgei are actually a result of sexual dimorphism within the same species.[1] The same analysis claims that Propelanomodon, another tuskless dicynodont genus, first described by Broom in 1913,[4] is in fact a juvenile form of Pelanomodon. The authors of this analysis would classify all these species as Pelanomodon moschops. The basis for these conclusions are discussed below.

Paleobiology

Sexual dimorphism

In the past, skull features have also been used to distinguish possible Pelanomodon species from one another.[5] However, more recent analysis suggests that these disparities between specimens may not suggest more than one species, but rather sexual dimorphism within the same species.[1] Two species have been previously classified, Pelanomodon moschops (P. moschops), identified by having a skull longer than 18 cm in length and relatively small cranial bosses and Pelanomodon rubidgei (P. rubidgei), identified by having a skull longer than 18 cm but with relatively large cranial bosses.[1] P. moschops and P. rubidgei have been hypothesized to be of the same species by several paleontologists, due to the fact that few structural differences exist between the skulls of the two species. The most prominent distinction between these two skull types is the presence and size of the cranial bosses.[1] P. moschops lacks the supraorbital ridge and postorbital bosses that are seen in P. rubidgei, and although it maintains the nasal and prefrontal bosses, they are much smaller.[1] Other than these seemingly superficial features, the species share all other cranial features. It is for this reason that it is hypothesized the differences are a result of sexual dimorphism within one species, P. moschops.

Ontogeny

Propelanomodon tylorhinus is another dicynodont species that has recently been hypothesized to be a juvenile form of P. moschops.[1] It has a shorter skull, typically shorter than 14 centimetres (5.5 in) long. Several key cranial features differ within this species when compared to P. moschops’ skulls, which leaves there to be debate among paleontologists about its relationship to Pelanomodon. For example, the temporal fenestra of Propelanomodon point anterposteriorly, rather than being angled slightly laterally.[1] As a result of this, its skull does not have the distinct triangular shape of Pelanomodon. In addition, Propelanomodon’s snout is relatively shorter and its orbits relatively larger. The cranial bosses that are very distinct of Pelanomodon are also absent, except for the nasal bosses. Supporters of this hypothesis claim that it is not unusual to see large cranial changes in vertebrae as they mature.[1]

Diet

Like other Dicynodonts, Pelanomodon is believed to have been an herbivore as its lack of canine teeth would inhibit it from having a carnivorous diet.[2] In addition, Pelanomodon is described to have a similar overall skull to Aulacephalodon. Keyser describes that the tip of the snout is supported by ridges along the palatal and snout's external surface which restricts the chewing motion to just the tip of the jaw.[5] This combined with some of the other cranial features described above, such as the placement of the nares and orbit, suggests that the animal may have consumed plants from shallow waters.[5]

Paleoecology

The fossil record of Pelanomodon has thus far been restricted to the Karoo Basin in Southern Africa.[1] This region chronicles constant sediment accumulation from the Carboniferous period and into the Jurassic period. Pelanomodon, along with other dicynodonts are predominantly found as a part of the Beaufort Group. The Beaufort Group geological strata ranges from the middle Permian to middle Triassic period. Sedimentary analysis suggests that during this time the region was characterized by the extensive flood plains of a few large rivers.[3] The climate during the late Permian period, in this region was semi-arid and rainfall was seasonal.[10] This climate, combined with the important role that rivers played in establishing the environment, allowed for a variety of riparian vegetation to grow, which in turn lead to a high diversity of animals that were all able to fill a different niche.[10] In fact, dicynodonts have been found to be the most abundant therapsid in this range.[11]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Kammerer, C. F., K. D. Angielczyk, and Jörg Fröbisch. 2015. Redescription of the geikiid Pelanomodon (Therapsida, Dicynodontia), with a reconsideration of ‘Propelanomodon’. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2015.1030408. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02724634.2015.1030408

- ^ a b c Toerien, M.J. (1954). "Convergent trends in anomodontia". Evolution. 9 (2): 152–156. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1955.tb01528.x.

- ^ a b Smith, Roger; Botha, Jennifer (2005). "The recovery of terrestrial vertebrate diversity in South African Karoo Basin after the end-Permian extinction". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 4 (6–7): 623–636. Bibcode:2005CRPal...4..623S. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2005.07.005.

- ^ a b c Broom, Robert (1913). "On some new genera and species of dicynodont reptiles, with notes on a few others". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 32: 441–457.

- ^ a b c d e Keyser, A.W (1969). Re-evaluation of the systematics and morphology of certain anomodont Therapsida. Ph.D. Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

- ^ a b Broom, Roger (1938). "On two new anomodont genera". Annals of the Transvaal Museum. 19: 247–250.

- ^ Broom, Robert (1940). "On some new genera and species of fossil reptiles from the Karroo beds of Graaff-Reinet". Annals of the Transvaal Museum. 20: 157–192.

- ^ Broom, Robert (1950). "Three new species of anomodonts from the Rubidge Collection". Annals of the Transvaal Museum. 21: 246–250.

- ^ C. F. Kammerer, K. D. Angielczyk, and J. Frobisch. 2011. A comprehensive taxonomic revision of Dicynodon (Therapsida, Anomodontia) and its implications for dicynodont phylogeny, biogeography, and biostratigraphy. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31(Sup, to 6):1-158

- ^ a b Smith, R.M.H; Botha, W.J. (1993). "A review of the stratigraphy and sedimentary environments of the Karoo-aged basins of Southern Africa". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 16 (1–2): 143–169. Bibcode:1993JAfES..16..143S. doi:10.1016/0899-5362(93)90164-l.

- ^ Hancox, P.J; Rubidge, B.S (2001). "Breakthroughs in the biodiversity, biogeography, biostratigraphy, and basin analysis of the Beaufort group". African Earth Sciences. 33 (3–4): 563–577. Bibcode:2001JAfES..33..563H. doi:10.1016/s0899-5362(01)00081-1.