Pearl Manuscript

| Pearl Manuscript | |

|---|---|

| British Library | |

The Green Knight at Camelot, folio 94v, and the beginning of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, folio 95r | |

| Also known as | The Gawain Manuscript, British Library MS Cotton Nero A X/2 |

| Date | c. 1400 |

| Place of origin | Northern England |

| Language(s) | Middle English |

| Author(s) | The Gawain Poet |

| Material | Vellum |

| Size | 12 centimetres (4.7 in) x 17 centimetres (6.7 in) |

| Format | Single column |

| Script | Gothic textura rotunda |

| Contents | Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, Cleanness, Patience |

| Previously kept | Cotton library |

The Pearl Manuscript (British Library MS Cotton Nero A X/2), also known as the Gawain manuscript,[1] is an illuminated manuscript produced somewhere in northern England in the late 14th century or the beginning of the 15th century. It is one of the best-known Middle English manuscripts,[2] the only one containing alliterative verse solely,[3] and the oldest surviving English manuscript to have full-page illustrations. It contains the only surviving copies of four of the masterpieces of medieval English literature: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, Cleanness, and Patience. It has been described as "one of the greatest manuscript treasures for medieval literature",[4] and "the most famous of all romance manuscripts".[5]

Contents

The titles given here are those used by modern editors, all the poems being untitled in the manuscript. It has been foliated twice, first in ink and later in pencil; the second foliation is used here.

- Pearl, ff. 41r–59v

- Cleanness (also known as Purity), ff. 60r–86r

- Patience, ff. 86r–94r

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, ff. 94v–130r

- A Middle English couplet beginning "Mi minde is mukul on on þat wil me noȝt amende", f. 129v

There are also a number of illustrations scattered throughout.[6][7]

Date and place of origin

The text of the Pearl Manuscript is commonly dated on palaeographical grounds to the last quarter of the 14th century, or at the latest to the beginning of the 15th century, the illustrations being added at either the same time as the text or a little later. It has also been argued that it was produced for the Stanley family by a scribe whose dialect locates him to south-east Cheshire or north-east Staffordshire.[8][9][10] In recent years several scholars have reidentified the scribe's dialect as Yorkshire, and Joel Fredell has pointed out stylistic and thematic similarities with illuminated manuscripts produced in York which suggest that the illustrations in Cotton Nero A X/2 were drawn and painted there in the first two decades of the 15th century.[11]

History of the manuscript

It is not known who owned the manuscript for the first two hundred years of its history. The name "Hugo de" appears on the margin of one leaf, and perhaps (though this is disputed) "J Macy" on another, either of which might be interpreted as a mark of either ownership or authorship. Edward Wilson has speculated that it was held by the Stanley family;[12] Elizabeth Salter that it formed part of the library of one Yorkshire monastery or another, and passed from them to the 16th-century collector John Nettleton.[13] The recorded history of the manuscript begins some time before 1614 with a description of it in the private library catalogue of the Yorkshire book-collector Henry Savile of Banke as "An owld booke in English verse beginninge Perle plesant to Princes pay in 4º. Limned". Before 1621 it was evidently acquired by Sir Robert Cotton, being then listed as "Gesta Arthuri regis et aliorum versu Anglico [Deeds of King Arthur and other matters in English verse]".[14][15] His librarian bound it along with two quite unrelated Latin texts,[16] from which it was not separated until a rebinding in 1964. A catalogue of Cotton's collection printed in 1696 mentioned this volume, and it was, along with all the Cotton family's other manuscripts, donated to the British Museum when that institution was founded in 1753. It is now held by the British Library.[10]

Description

The manuscript consists of 90 vellum folios now measuring 12 centimetres (4.7 in) by 17 centimetres (6.7 in), though it seems to have been cropped from a larger size. The quiring comprises a single bifolium followed by seven gatherings of twelve leaves each and a single gathering of four leaves.[17] Folio 39r, the first page of Pearl, is stained enough to suggest that the manuscript was once unbound and that this was its outer sheet. Most pages are ruled to allow for 36 lines of text.[18] All four of the main poems in the manuscript were written by a single scribe using a Gothic textura rotunda script rather than the cursiva script that would be more usual in a late 14th-century vernacular poetry manuscript. The hand has been described as "distinctive, rather delicate [and] angular". The scribe's irregularity in following the ruled lines and his heavy use of abbreviations and ligatures has led to the suggestion that he was more used to notarial than literary work.[19][20][21] Some letters which had faded or blurred have been redone by a later scribe, and this process of fading has continued; during the century that has passed since 1923 that year's EETS facsimile edition has become in many places more easily readable than the manuscript itself.[19] There are 48 decorated initials in the manuscript, all written in blue with red penwork, which range in size from fifteen to two lines. It has often been argued that they were used to make clear the internal structure of each of the four poems.[22]

Illustrations

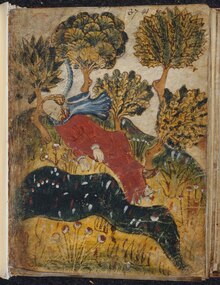

The manuscript has twelve illustrations: four on ff. 41r–42v (immediately before Pearl), showing the dreamer sleeping, the dreamer approaching the stream, the dreamer seeing the maiden, and the dreamer trying to cross; two on ff. 60r–60v (immediately before Cleanness), showing Noah's Ark and Daniel at Belshazzar's feast; two on ff. 86r–86v (immediately before Patience), showing Jonah and the whale and Jonah preaching to the people of Nineveh; one on ff. 94v (immediately before Sir Gawain), showing the Green Knight at Camelot; and three on 129r–130r (immediately after Sir Gawain), showing Bertilak's wife tempting Sir Gawain, Gawain at the Green Chapel, and Gawain's return to Camelot.[7] With one exception they all take up a complete side of a folio, a feature not found in any earlier English manuscript.[23] They all depict scenes described in the four poems though not always with perfect accuracy, suggesting that the illustrator had not read them but was instead following suggestions from the manuscript's owner.[24] They were created in two stages: first in black-and-white as ink drawings, then as paintings with the colour being applied with considerably less skill, perhaps by a different artist.[25] Their overall quality was roundly abused by some 20th century critics, described as "crude and inartistic" by E. V. Gordon,[26] and "the nadir of English illustrative art...infantile daubs" by R. S. and L. H. Loomis;[27] more recently Kathleen L. Scott considered them the work of a professional, Sarah M. Horrall described them as "very competently executed",[23] and Joel Fredell has judged them to be skilled work comparable to the miniatures of the Bolton Hours, if inferior to London work and the products of the International Gothic style.[28]

Transmission of the text

The Pearl manuscript's scribe was not the author of the poems it contains, and indeed the number and nature of its scribal errors and textual anomalies show it to stand at some distance from the original manuscript or manuscripts. At least one line, and possibly several more, have been lost from the original poems, while others seem to have been rearranged or added.[29] It may have been an inept copy of a prestige illuminated manuscript commissioned by some wealthy patron.[30] It has also been suggested that the Pearl manuscript or its exemplar may have collected each of its four texts from a different manuscript.[31]

First publication

The first published quotations from Cotton Nero A X/2 appeared in a footnote in the third volume of Thomas Warton's History of English Poetry in 1781, comprising twelve lines from Pearl and four from Cleanness. A further short quotation from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight was included in a footnote to Richard Price's new edition of Warton's History in 1824,[32] and the poem was published in its entirety, edited by Frederic Madden, in 1839. Pearl, Patience and Cleanness were not edited until 1864, by Richard Morris.[33]

Editions

Editions of the full contents:

- Gollancz, Israel, ed. (1923). Pearl, Cleanness, Patience and Sir Gawain, Reproduced in Facsimile from the Unique MS. Cotton Nero A.x in the British Museum. Early English Text Society Original Series, 162. London: Oxford University Press.

- Cawley, A. C.; Anderson, J. J., eds. (1976). Pearl, Cleanness, Patience, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. London: Dent. ISBN 0460103466.

- Moorman, Charles, ed. (1977). The Works of the Gawain-Poet. Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi Press. ISBN 9780878050284.

- Vantuono, William, ed. (1984). The Pearl Poems: An Omnibus Edition. The Renaissance Imagination, 5 and 6. New York: Garland. ISBN 0824054504.. In two volumes.

- Andrew, Malcolm; Waldron, Ronald, eds. (2007). The Poems of the Pearl Manuscript: Pearl, Cleanness, Patience, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (5th ed.). Exeter: University of Exeter Press. ISBN 9780859897914. This is considered the reference edition.[33]

Translations

Translations of the full contents:

- Gardner, John (1965). The Complete Works of the Gawain-Poet. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226283302.

- Andrew, Malcolm; Waldron, Ronald, eds. (1993). The Complete Works of the Pearl Poet. Translated by Finch, Casey. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520078710.

Footnotes

- ^ Cassidy, Seamus; McGarvey, Erin; Normesinu, Isaac. "Cotton Nero A.X". Mediakron. Boston College. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

Informally, Cotton Nero A.X is referred to as 'the Pearl Manuscript' or, less often, 'the Gawain Manuscript'.

- ^ Booher, Dustin; Gunn, Kevin B. (2020). Literary Research and the Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Eras: Strategies and Sources. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 183. ISBN 9781538138434. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Doyle, A. I. (1982). "The manuscripts". In Lawton, David (ed.). Middle English Alliterative Poetry and Its Literary Background: Seven Essays. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. p. 93. ISBN 9780859910972. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Fredell 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Johnston, Arthur (1964). Enchanted Ground: The Study of Medieval Romance in the Eighteenth Century. London: University of London, Athlone Press. p. 114. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Edwards 1997, pp. 197, 200.

- ^ a b Brantley 2022, p. 218.

- ^ Roberts 2018, p. 1.

- ^ Edwards 1997, pp. 197–199.

- ^ a b "Four anonymous poems in Middle English: Pearl, Cleanness, Patience and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Cotton MS Nero A X/2: 1375-1424". Explore Archives and Manuscripts. British Library. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ Fredell 2014, pp. 3–4, 13–33.

- ^ Edwards 1997, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Salter, Elizabeth (1983). Fourteenth-Century English Poetry: Contexts and Readings. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 019811186X. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ Gordon 1970, p. ix.

- ^ Edwards 1997, p. 198.

- ^ Putter 2014, p. 1.

- ^ Edwards 1997, p. 197.

- ^ Roberts 2018, p. 2.

- ^ a b Silverstein 1984, p. 15.

- ^ Fredell 2014, pp. 25, 27.

- ^ Roberts 2018, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Edwards 1997, p. 201.

- ^ a b Reichardt 1997, p. 120.

- ^ Edwards 1997, pp. 210, 213.

- ^ McGillivray, Murray; Duffy, Christina (October 2017). "New light on the Sir Gawain and the Green Knight manuscript: multispectral imaging and the Cotton Nero A.x. illustrations". Speculum. 92 (1): 113–114, 122–123. doi:10.1086/693361. S2CID 165540619. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ Gordon 1970, p. x.

- ^ Edwards 1997, p. 218.

- ^ Fredell 2014, p. 25.

- ^ Edwards 1997, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Putter 2014, p. 23.

- ^ Edwards 1997, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Burrow, J. A. (2001). The Gawain-Poet. Tavistock: Northcote House. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9780746308783. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ a b Schmidt 2010, p. 369.

References

- Brantley, Jessica (2022). Medieval English Manuscripts and Literary Forms. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812253849. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- Edwards, A. S. G. (1997). "The manuscript: British Library MS Cotton Nero A.x". In Brewer, Derek; Gibson, Jonathan (eds.). A Companion to the Gawain-Poet. Arthurian Studies, 38. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. p. 195. ISBN 9780859915298. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- Fredell, Joel (2014). "The Pearl-Poet manuscript in York". Studies in the Age of Chaucer. 36: 1–39. doi:10.1353/sac.2014.0004. S2CID 161651298. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- Gordon, E. V. (1970). Pearl. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198113799. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- Putter, Ad (2014). An Introduction to the Gawain-Poet. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780582225749. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- Reichardt, Paul F. (1997). "'Several illuminations, coarsely executed': the illustrations of the Pearl manuscript". Studies in Iconography. 18: 119–142. JSTOR 23924071.

- Roberts, Jane (31 January 2018). "The Hand and Script" (PDF). The Cotton Nero A.x. Project. University of Calgary. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Schmidt, A. V. C. (2010). "The poet of Pearl, Cleanness and Patience". In Saunders, Corinne (ed.). A Companion to Medieval Poetry. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 369–384. ISBN 9781405159630. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- Silverstein, Theodore, ed. (1984). Sir Gawain & the Green Knight: A New Critical Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226757674. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

External links

- Digital Facsimile of the Manuscript

- The Cotton Nero A.x. Project at the University of Calgary