Partimento

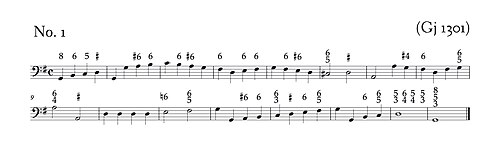

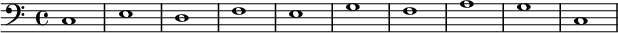

A Partimento (from the Italian: partimento, plural partimenti) is a sketch (often a bass line), written out on a single staff, whose main purpose is to be a guide for the improvisation ("realization") of a composition at the keyboard.[1] A Partimento differs from a basso continuo accompaniment in that it is a basis for a complete composition.[2] Partimenti were central to the training of European musicians from the late 1600s until the early 1800s. They were developed in the Italian conservatories, especially at the music conservatories of Naples, and later at the Paris Conservatory, which emulated the Neapolitan conservatories.[3]

Concept

Giorgio Sanguinetti wrote that it was not easy to explain what was a partimento. It was not a basso continuo, for it did not accompany another part. It was not a figured bass, for Neapolitan partimenti were rarely figured. While a bass, it could as well be a soprano or other voice. Though written, its goal was improvisation. And, although it was an exercise in composition, it was also an art form in its own right.

So, what is a partimento? A good definition is a metaphor: a partimento is a thread that contains in itself all, or most, of the information needed for a complete composition... The partimento ... is a linear entity that runs from the beginning to the end of a (potential) composition.[4]

History

Beginnings

Partimenti evolved in the late 17th century in educational milieus in Bologna, Rome, and Naples, originally out of the tradition of organ and harpsichord improvisation.[6] The earliest dated collection of partimenti with a known author is attributed to Bernardo Pasquini in the first decade of the 18th century.[7]

Golden age

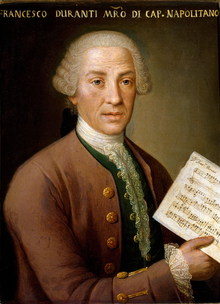

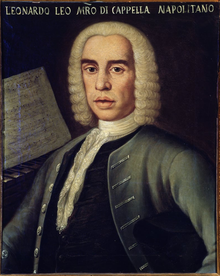

The golden age of partimento was presided over by Alessandro Scarlatti and his pupils Francesco Durante and Leonardo Leo.[8] Many important Italian composers emerged from the musical institutions in Naples, Bologna, and Milan, such as Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Giuseppe Verdi, Domenico Cimarosa, Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, Gaspare Spontini and Gioachino Rossini.

Partimenti collections in Germany

The Langloz manuscript, a collection of preludes and fugues that possibly represent the pedagogical and compositional method of Johann Sebastian Bach,[9] is regarded as a collection of German partimenti.[10] Princess Anne's music lessons with Georg Frideric Handel included the use of partimenti exercises.[11] Other collections of German partimenti include Johann Mattheson's forty-eight Probestücke from his Exemplarische Organisten-Probe and Gottfried Kirchhoff's collection of preludes and fugues.[12]

Influence on Paris Conservatory

The Paris Conservatory was greatly influenced by the music conservatories of Naples. Much of the Neapolitan syllabus was renamed "Harmony" at the Paris Conservatory, which included improvising "practical harmony" with partimenti played at a piano, and "harmony" as a written subject where additional voices were added to a given voice such as a bass or soprano. The resulting multi-voice counterpoint in Soprano, Alto, Tenor and Bass clefs were called a realization (réalisation). A student would begin by playing basic material as a 10- or 11 year-old but would eventually mature to write complicated four-voice counterpoint full of distant modulations and chromatic embellishments.[13] François Bazin was a teacher of harmony at the Paris conservatory and many of his lessons were still titled "partimenti".[14]

Revival in the 21st century

The rediscovery of the partimento tradition in modern research since around 2000 has enabled new ways of looking at the musical education and composing practice in the 18th and 19th centuries, nurturing musical creativity beyond mere partimento realizations. Influential monographs concerning partimento include Robert O. Gjerdingen's Music in the Galant Style (2007) and Giorgio Sanguinetti's The Art of Partimento (2012). Partimenti gained increased recognition due to being part of Alma Deutscher's early musical training, with her studies with Tobias Cramm and Robert Gjerdingen.[a][15]

Partimento rules

Several Neapolitan teachers such as Fedele Fenaroli, Giovanni Furno and Giaocomo Insanguine published collections of regole (rules) and partimenti that were popular pedagogical materials across Europe. In particular, Fenaroli's Regole enjoyed a long publishing life, from the first edition 1775 to the final edition in 1930.[16]

To begin with, one will play all unfigured basses with simple consonant chords: from that performance the Master will clearly understand if his pupil has correctly understood the principles thereof. Secondly, one shall introduce all feasible dissonances for that given bass. Lastly, one shall shape the properly said imitation.

— Emanuele Guarnaccia, Metodo nuovamente riformato de'partimenti, 3, 1825 ca, [17]

Partimenti were typically used as exercises to train conventional models of voice leading, harmony, and musical form, such as the so-called rule of the octave (the harmonized scale), cadences and sequences (the movimenti, or moti del basso). The beginners’ partimenti treatises usually present rules, which are then followed by exercises of increasing difficulty, presenting figured bass as well as unfigured bass lines, and culminating in the advanced exercises of imitative partimenti and partimento fugues.

Consonances and dissonances

Music is composed of consonances and dissonances.[18]

Consonances

The four consonances were the 3rd, 5th, 6th and 8th. The 5th and 8th were perfect consonances because, at the time, it was believed that one couldn't make distinctions between them by expanding them with a sharp or diminishing them by altering a natural or an accidental. Of course, in reality you can: there are augmented and diminished fifths and octaves. The 3rd and 6th were considered imperfect consonances because one can make distinctions between them.[19]

There's a prohibition against an octave or a fifth moving in parallel because, due to an octave or fifth's perfection, moving one creates no variation in harmony, and these [perfect intervals] are the fundamental basses that rule the key.[20]

Dissonances

The four dissonances are the 2nd, 4th, 7th and 9th. They were invented to make the consonances sound more beautiful. These cannot be used unless prepared by a preceding consonance and subsequently resolved to one of the aforementioned consonances.[21]

Essential foundations of the key

The essential foundations of the key[20] or rule of the scale steps[22] tell the student how to distribute chords over scale degrees, separate from the rule of the octave.[23]

One can give an 8ve to all the degrees of the key, as well as to their consonances, provided that one does not create parallel 8ves, seeing that two 5ths or 8ves, whether above or below, by step or by skip, the one after the other, are prohibited because they make bad harmony.

① takes a 3rd, 5th.

② takes a minor 3rd, 4th and major 6th. [24]

③ takes a 3rd and 6th. Both of them should be minor if the said ③ is major. If, on the other hand, the said ③ is minor, then it takes the major 3rd and major 6th, and this comes about naturally.

④ takes a 3rd and 5th. Whenever the ④ ascends to the ⑤, it [④] can take the 6th in addition to the 3rd and 5th. And if ④ descends from ⑤, then stay with the same consonances as for the said ⑤, which become in turn a 2nd, major [=augmented] 4th, and 6th.

⑤ takes a major 3rd and 5th. Give a minor seventh to a ⑤ that returns to the ①. This seventh cannot rise, but must resolve by falling to the third of the ①.

⑥ takes a 3rd, and 6th. When ⑥ is major and descends to ⑤, then it is better to use a major 6th in the accompaniment, because it makes better harmony. And one can add to ⑥, as if it were ②, by giving it a 3rd, a 4th, and a major 6th. But if the ⑥ neither ascends to ⑦ or descends to ①, then give it a 3rd and 5th.

⑦ takes a 3rd and 6th. Both of them should be minor if the said ⑦ is major. If, on the other hand, the ⑦ is minor, then the 3rd and the 6th in the accompaniment should both be major, and this comes about naturally. Give a diminished fifth to a ⑦ rising to the ①, in addition to the 3rd and 6th. This diminished fifth cannot rise, but must also resolve by falling to the third of the ①.

Cadences

A cadence is when the bass goes from ① to ⑤, and [then] from ⑤ to ①.[25] There are three types of cadences: Simple, Compound and Double.[26]

Simple cadence

A simple cadence is when one gives the bass the simple consonances required by both ① and ⑤. That is, the ① takes the 3rd and 5th, and the ⑤ takes the major 3rd and 5th.

Compound cadence

A compound cadence is when, above ⑤, one makes a dissonance of a 4th prepared by the 8ve of ① and resolved to the major 3rd of ⑤.

Double cadence

A double cadence is when, above ⑤, one puts the major 3rd and 5th, the 6th and 4th, the 5th and 4th, and then the major 3rd and 5th.

Rule of the octave

After learning cadences, students at the Neapolitan conservatories were immediately taught the rule of the octave, or scale as they were termed in Naples.[27]

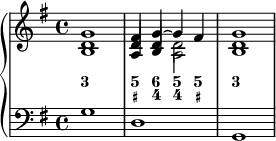

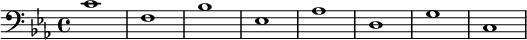

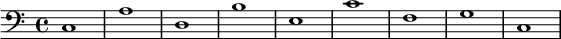

Major mode

Rule of the octave ascending in G major, in 1st position.

Rule of the octave descending in G major, in 1st position.

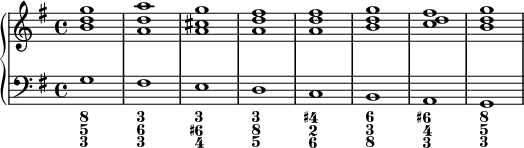

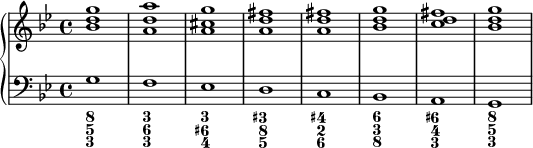

Minor mode

Rule of the octave ascending in G minor, in 1st position.

Rule of the octave descending in G minor, in 1st position.

Suspensions

According to partimento theory, it is only suspensions that are deemed to be dissonances.[28]

Bass motions

In addition to the rule of the octave, bass motions are fundamental to partimento theory. The ability to identify bass motions in a partimento allows the performer to choose appropriate chords. Bass motions move in a conjunct (stepwise, including chromatic) motion or disjunct motion (sequences).[29]

Rises by a 3rd and falls by a step

Falls by a 3rd and rises by a step

Rises by a 4th and falls by a 3rd

Falls by a 4th and rises by a step

Rises by a 4th and falls by a 5th

Falls by a 5th and rises by a 4th

Rises by a 5th and falls by a 4th

Rises by a 6th and falls by a 5th

Falls by semitone

Rises by semitone

Falls with ties

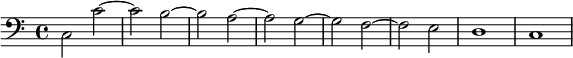

Diminution

The art of turning a basic, slow melody into a more florid, rapid one is called diminution.[30]

Imitation

[Imitations] occur when the right hand imitates, that is answers to, the motive of the bass, that the left hand has played; or rather, when the right hand anticipates the motive that the left hand will play shortly after.

— Pellegrino Tomeoni, Regole pratiche per accompagnare il basso continuo,39, [31]

Imitation works to improve a basic accompaniment-like realization into a more proper composition.[32] It is also an important preparatory training for partimento fugues.[33]

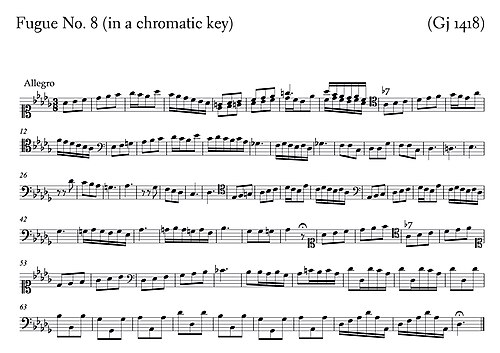

Partimento fugues

The culmination of partimento training is the realization of partimento fugues.[34]

Partimento and counterpoint

For those who want to learn counterpoint, it is necessary first to thoroughly study the first and second books of partimenti, and then the moti del basso of the third book.

— Fedele Fenaroli, Studio de Contrapunto del Sig I-Nc 22-2-6/2, fol. 1, [35]

Partimenti were also used as bass lines in written counterpoint exercises, over which students wrote two-, three, and four-part “disposizione” (multistave settings).

Notable collections of partimenti

Notable partimento collections were written by Alessandro Scarlatti, Francesco Durante, Leonardo Leo, Fedele Fenaroli, Giovanni Paisiello, Nicola Sala, Giacomo Tritto, Stanislao Mattei.

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Her father, Israeli linguist Guy Deutscher, said, “The greatest moment was when we realized that she was playing her own melodies.” He decided to take Alma’s musical soul seriously, and began searching for methods of teaching classical music composition to children—and for a teacher.He discovered a book, Music in the Galant Style, by Robert Gjerdingen, professor of music at North-western University’s School of Music. Gjerdingen reveals the results of his exhaustive search through the libraries of Naples and other Italian cities to and the original sources, the pedagogical workbooks, known as partimenti (or singular, partimento, using the word to mean the method itself) of 18th-century music masters.

References

Citations

- ^ Sanguinetti 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Sanguinetti 2012, p. 167.

- ^ The History of Partimenti Monuments of Partimenti

- ^ Sanguinetti 2007, p. 51.

- ^ Sanguinetti 2012, p. 70.

- ^ Sanguinetti 2012, p. 69.

- ^ Sanguinetti 2012, p. 20.

- ^ Sanguinetti 2012, p. 67.

- ^ Byros 2015, p. 1.3.

- ^ Byros 2015, p. 1.1.

- ^ Gjerdingen 2007b, p. 28.

- ^ Byros 2015, p. 5.1.

- ^ Gjerdingen 2019, p. [1].

- ^ Gjerdingen 2020, p. 296.

- ^ Rasmussen 2017, p. 25.

- ^ Sanguinetti 2012, p. 78.

- ^ Guarnaccia 1825, p. 3.

- ^ Fenaroli 1775, p. 2.

- ^ Fenaroli 1775, p. 3.

- ^ a b Fenaroli 1775, p. 4.

- ^ Fenaroli 1775, p. 14.

- ^ Furno 1817, p. 2.

- ^ Sanguinetti 2012, p. 117.

- ^ Furno 1817, p. 3.

- ^ Fenaroli 1775, p. 7a.

- ^ Fenaroli 1775, p. 7b.

- ^ a b Sanguinetti 2012, p. 114.

- ^ Sanguinetti 2012, p. 125.

- ^ Sanguinetti 2012, p. 135.

- ^ Sanguinetti 2012, p. 183.

- ^ Tomeoni 1795.

- ^ Sanguinetti 2012, p. 191a.

- ^ Sanguinetti 2012, p. 191b.

- ^ Gjerdingen 2020, p. 122.

- ^ van Tour 2015, p. 162.

Sources

- Byros, Vasili (2015), "Prelude on a Partimento: Invention in the Compositional Pedagogy of the German States in the Time of J. S. Bach", Music Theory Online, 21 (3), Society for Music Theory, doi:10.30535/mto.21.3.3, retrieved 23 May 2020

- Fenaroli, Fedele (1775), Regole musicali per i principianti di cembalo (in Italian), Vincenzo Mazzola-Vocola, retrieved 23 May 2020

- Furno, Giovanni (1817), Metodo facile breve e chiaro delle prime ed essensiali regole per accompagnare partimenti senza numeri (PDF) (in Italian and English), Naples, retrieved 23 May 2020

- Gjerdingen, Robert O. (2007a), "Partimento, Que Me Veux-Tu?", Journal of Music Theory, 52 (1), Duke University Press: 85–135, doi:10.1215/00222909-2008-024, JSTOR 40283109

- Gjerdingen (2007b), Music in the Galant Style, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195313710

- Gjerdingen, Robert O. (2007c), "Images of Galant Music in Neapolitan Partimenti and Solfeggi" (PDF), Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis, 31: 131–148, S2CID 44705218, archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2020, retrieved 23 May 2020

- Gjerdingen, Robert O. (2009), The Perfection of Craft Training in the Neapolitan Conservatories (PDF), vol. 15, Rivista di Analisi e Teoria Musicale, pp. 26–49, retrieved 23 May 2020

- Gjerdingen (2010a), "Partimenti Written to Impart a Knowledge of Counterpoint and Composition" (PDF), Partimento and Continuo Playing in Theory and in Practice, Partimento and Continuo Playing in Theory and Practice: Collected Writings of the Orpheus Institute 9, 43–70. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 43–70, doi:10.2307/J.CTT9QDXDV.5, ISBN 9789461660947, S2CID 194145754, archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-08, retrieved 24 May 2020

- Gjerdingen (2010b), A Source of Pasquini Partimenti in Naples, Atti del Convegno su Pasquini, pgs 61-82, Smarano, It.

- Gjerdingen (2019). "Partimento.org".

- Gjerdingen (2020), Child Composers in the Old Conservatories: How Orphans Became Elite Musicians, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780190653590

- Guarnaccia (1825), Metodo nuovamente riformato de'partimenti...dal maestro Emanuele Guarnaccia, Milan, Ricordi

- Rasmussen, Michelle (2017), "The Inner Workings of Alma Deutscher's Musical Genius", Executive Intelligence Review, 44 (21): 23–28, retrieved 23 May 2020

- Sanguinetti, Giorgio (2007), "The Realization of Partimenti: An Introduction", Journal of Music Theory, 51 (1), Duke University Press: 51–83, doi:10.1215/00222909-2008-023

- Sanguinetti, Giorgio (2012), The Art of Partimento, Oxford University Press., ISBN 9780195394207

- Tomeoni, Pellegrino (1795), Regole Pratiche Per Accompagnare Il Basso Continuo Esposte in Dialoghi Per Facilitare Il Possesso Alla Principiante Gioventù (in Italian), Florence

- van Tour, Peter (2015), Counterpoint and Partimento: Methods of Teaching Composition in Late Eighteenth-Century Naples, Upsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, ISBN 978-91-554-9197-0

Further reading

- Cafiero, Rose (2007), "The Early Reception of Neapolitan Partimento Theory in France: A Survey", Journal of Music Theory, 51 (1), Duke University Press: 137–159, doi:10.1215/00222909-2008-025, JSTOR 40283110

- Cipriani, Benedetto (2019), Nadia Amendola; Alessandro Cosentino; Giacomo Sciommeri (eds.), "La didattica musicale del partimento: la situazione del contesto romano tra figure chiave e nuove fonti", 1st Young Musicologists and Ethnomusicologists International Conference. Music, Individuals and Contexts. Dialectical Interaction, SEDM – Società Editrice di Musicologia: 131–144, ISBN 9788832932645

- Demeyere, Ewald (2018), "On Fedele Fenaroli's Pedagogy: An Update", Eighteenth Century Music, 15 (2), Cambridge University Press: 207–229, doi:10.1017/S1478570618000052, S2CID 165216708

- Diergarten, Felix (2011), "'The True Fundamentals of Composition': Haydn's Partimento Counterpoint", Eighteenth-Century Music, 8 (1), Cambridge University Press: 53–75, doi:10.1017/S1478570610000412 (inactive 2024-11-13), S2CID 162334701

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - IJzerman, Job (2018), Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento: A New Method Inspired by Old Masters, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780190695019

- Khoury, Stephanie (2014), "Partimento as Improvisation Pedagogy: Renewing a Lost Art", Revista InCantare, 5 (2), Curitiba: 87–101, ISSN 2317-417X, retrieved 23 May 2020

- Lodewyckx, David; Bergé, Pieter (2014), "Partimento, Waer bestu bleven? Partimento in the European Classroom: Pedagogical Considerations and Perspectives", Music Theory & Analysis, 1 (1 & 2), Leuven University Press: 146–169, doi:10.11116/MTA.1.9

- Mortensen, John (2020) The pianist's guide to historic improvisation. Oxford University Press.

- Paraschivescu, Nicoleta (2017), Die Partimenti Giovanni Paisiellos Wege zu einem praxisbezogenen Verständnis (in German), Basel: Schwabe Verlag, ISBN 978-3796537240

- Rabinovitch, Gilad; Slominski, Johnandrew (2015), "Towards a Galant Pedagogy: Partimenti and Schemata as Tools in the Pedagogy of Eighteenth-Century Style Improvisation", Music Theory Online, 21 (3), doi:10.30535/mto.21.3.10, retrieved 23 May 2020

- Sanguinetti, Giorgio (2005), "Decline and Fall of the 'Celeste Impero': the Theory of Composition in Naples during the Ottocento", Studi Musicali, XXXIV (2): 451–502, retrieved 23 May 2020

- Serebrennikov, Maxim (2009), "From Partimento Fugue to Thoroughbass Fugue: New Perspectives", Bach, 40 (2), Riemenschneider Bach Institute: 22–44, JSTOR 41640589

- van Tour, Peter (2017a), The 189 Partimenti of Nicola Sala: Complete Edition with Critical Commentary, Uppsala, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, ISBN 978-91-554-9778-1

- van Tour, Peter (2017b), Partimento Teaching according to Durante, Investigated through the Earliest Manuscript Sources, Studies in Historical Improvisation: From Cantare Super Librum to Partimento, London: Routledge, pp. 131–148, ISBN 978-1-472-47327-1

- van Tour (2018), "Improvised and Written Canons in Eighteenth-Century Neapolitan Conservatories", Journal of the Alamire Foundation (10), Turnhout: Brepols Publishers: 133–146, ISSN 2032-5371

- van Tour (2019), "Taking a walk at the Molo': Partimento and the Improvised Fugue", Speculum Musicae, Musical Improvisation in the Baroque Era (33), Turnhout: Brepols: 371–382, ISBN 978-2-503-58369-3

- van Tour, Peter (2020), "Integrating Aural and Keyboard Skills in Today's Classroom: Modern Perspectives on Eighteenth-Century Partimento Practices", Keyboard Skills in Musical Education: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Freiburg: Freiburg Hochschule

- Montagnier, Jean-Paul C. (2021), "Nicolas Bernier's Principe de composition and the Italian Partimento tradition", Early Music, XLIX (1), Oxford University Press: 87–99, doi:10.1093/em/caab004

External links

- Monuments of Partimenti

- The Uppsala Partimento Database, UUPart. Compiled and edited by Peter van Tour. Launched 2015, Uppsala.

- Partimenti of Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725) (D-Hs M/A 251)

- Partimenti of Francesco Durante (1684–1755) (I-MOe Campori γ L.9.26)

- Partimenti of Francesco Durante (1684–1755) (I-Bc EE.171)

- Partimenti of Leonardo Leo (1694–1744) (I-Bc DD.219)

- Partimenti of Pasquale Cafaro (1715–1787) (I-Bc DD.219)

- Partimenti of Giuseppe Giacomo Saratelli (1684–1762) (D-Mbs Mus. Ms. 1696)

- Partimenti of Carlo Cotumacci (1709–1785) (I-Nc 34.2.2)

- Partimenti of Niccolò Zingarelli (1752–1837) (I-Nc 34.2.10)