Pancreaticoduodenectomy

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | |

|---|---|

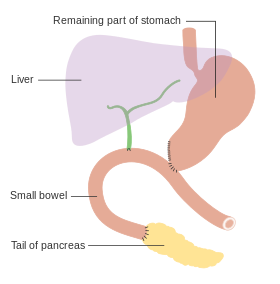

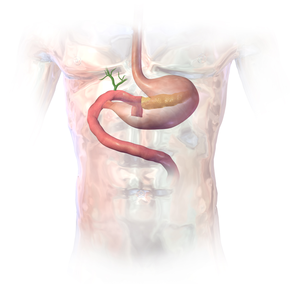

The pancreas, stomach, and bowel are joined back together after a pancreaticoduodenectomy | |

| Other names | Pancreatoduodenectomy,[1] Whipple procedure, Kausch-Whipple procedure |

| ICD-9-CM | 52.7 |

| MeSH | D016577 |

A pancreaticoduodenectomy, also known as a Whipple procedure, is a major surgical operation most often performed to remove cancerous tumours from the head of the pancreas.[2] It is also used for the treatment of pancreatic or duodenal trauma, or chronic pancreatitis.[2] Due to the shared blood supply of organs in the proximal gastrointestinal system, surgical removal of the head of the pancreas also necessitates removal of the duodenum, proximal jejunum, gallbladder, and, occasionally, part of the stomach.[2]

Anatomy involved in the procedure

The most common technique of a pancreaticoduodenectomy consists of the en bloc removal of the distal segment (antrum) of the stomach, the first and second portions of the duodenum, the head of the pancreas, the common bile duct, and the gallbladder. Lymph nodes in the area are often removed during the operation as well (lymphadenectomy). However, not all lymph nodes are removed in the most common type of pancreaticoduodenectomy because studies showed that patients did not benefit from the more extensive surgery.[3]

At the very beginning of the procedure, after the surgeons have gained access to the abdomen, the surfaces of the peritoneum and the liver are inspected for disease that has metastasized. This is an important first step as the presence of active metastatic disease is a contraindication to performing the operation.

The vascular supply of the pancreas is from the celiac artery via the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery and the superior mesenteric artery from the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery. There are additional smaller branches given off by the right gastric artery which is also derived from the celiac artery. The reason for the removal of the duodenum along with the head of the pancreas is that they share the same arterial blood supply (the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery and inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery). These arteries run through the head of the pancreas so that both organs must be removed if the single blood supply is severed. If only the head of the pancreas were removed it would compromise blood flow to the duodenum, resulting in tissue necrosis.

While the blood supply to the liver is left intact, the common bile duct is removed. This means that while the liver remains with a good blood supply the surgeon must make a new connection to drain bile produced in the liver. This is done at the end of the surgery. The surgeon will make a new attachment between the pancreatic duct and the jejunum or stomach. During the surgery, a cholecystectomy is performed to remove the gallbladder. This portion is not done en bloc, as the gallbladder is removed separately.

Relevant nearby anatomy not removed during the procedure include the major vascular structures in the area: the portal vein, the superior mesenteric vein, and the superior mesenteric artery, the inferior vena cava. These structures are important to consider in this operation especially if done for resection of a tumor located in the head of the pancreas.

Medical indications

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is most often performed as a curative treatment for periampullary cancer, which includes cancer of the bile duct, duodenum, ampulla or head of the pancreas.[4] The shared blood supply of the pancreas, duodenum and common bile duct necessitates en bloc resection of these multiple structures. Other indications for pancreaticoduodenectomy include chronic pancreatitis, benign tumors of the pancreas, cancer metastatic to the pancreas, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1[5] and gastrointestinal stromal tumors.[4]

Pancreatic cancer

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is the only potentially curative intervention for malignant tumors of the pancreas.[6] However, the majority of patients with pancreatic cancer present with metastatic or locally advanced un-resectable disease;[7] thus only 15–20% of patients are candidates for the Whipple procedure. Surgery may follow neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which aims to shrink the tumor and increase the likelihood of complete resection.[8] Post-operative death and complications associated with pancreaticoduodenectomy have become less common, with rates of post-operative mortality falling from 30 to 10% in the 1980s to less than 5% in the 2000s.[9]

Ampullary cancer

Ampullary cancer arises from the lining of the ampulla of Vater.[10]

Duodenal cancer

Duodenal cancer arises from the lining of the duodenal mucosa. Majority of duodenal cancers originate in the second part of the duodenum, where ampulla is located.[10]

Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangiocarcinoma, or cancer of the bile duct, is an indication for the Whipple procedure when the cancer is present in the distal biliary system, usually the common bile duct that drains into the duodenum. Depending on the location and extension of the cholangiocarcinoma, curative surgical resection may require hepatectomy, or removal of part of the liver, with or without pancreaticoduodenectomy.[11]

Chronic pancreatitis

Treatment of chronic pancreatitis typically includes pain control and management of exocrine insufficiency. Intractable abdominal pain is the main surgical indication for surgical management of chronic pancreatitis.[12] Removal of the head of the pancreas can relieve pancreatic duct obstruction associated with chronic pancreatitis.[13]

Trauma

Damage to the pancreas and duodenum from blunt abdominal trauma is uncommon. In rare cases when this pattern of trauma has been reported, it has been seen as a result of a lap belt in motor vehicle accidents.[14] Pancreaticoduodenectomy has been performed when abdominal trauma has resulted in bleeding around the pancreas and duodenum, damage to the common bile duct, pancreatic leakage, or transection of the duodenum.[15] Due to the rarity of this procedure in the setting of trauma, there is not robust evidence regarding post-operative outcomes.

Contraindications

In order to be considered for surgical removal, the tumor cannot encase more than 50% of any of the following vessels: the celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery, or inferior vena cava. In cases where less than 50% of the vessel is involved, vascular surgeons remove the involved portion of the vessel, and repair the residual artery or vein.[16] Tumors are still borderline resectable even if they involve the superior mesenteric or portal veins, gastroduodenal artery, superior mesenteric vein or colon. [17]

Metastatic disease is another contradiction to surgery. It most often occurs in the peritoneum, in the liver, and in the omentum. In order to determine if there are metastases, surgeons will inspect the abdomen at the beginning of the procedure after gaining access. Alternatively, they may perform a separate procedure called a diagnostic laparoscopy which involves insertion of a small camera through a small incision to look inside the abdomen. This may spare the patient the large abdominal incision that would occur if they were to undergo the initial part of a pancreaticoduodenectomy that was cancelled due to metastatic disease.[18]

Further contraindications include encasement of major vessels (such as celiac artery, inferior vena cava, or superior mesenteric artery) as mentioned above.

Surgical considerations

Pylorus-sparing pancreaticoduodenectomy

Clinical trials have failed to demonstrate significant survival benefits of total pancreatectomy, mostly because patients who submit to this operation tend to develop a particularly severe form of diabetes mellitus called brittle diabetes. Sometimes the pancreaticojejunostomy may not hold properly after the completion of the operation and infection may spread inside the patient. This may lead to another operation shortly thereafter in which the remainder of the pancreas (and sometimes the spleen) is removed to prevent further spread of infection and possible morbidity. In recent years the pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (also known as Traverso–Longmire procedure/PPPD) has been gaining popularity, especially among European surgeons. The main advantage of this technique is that the pylorus, and thus normal gastric emptying, should in theory be preserved.[19] There is conflicting data as to whether pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy is associated with increased likelihood of gastric emptying.[20][21] In practice, it shows similar long-term survival as a Whipple's (pancreaticoduodenectomy + hemigastrectomy), but patients benefit from improved recovery of weight after a PPPD, so this should be performed when the tumour does not involve the stomach and the lymph nodes along the gastric curvatures are not enlarged.[21]

Compared to the standard Whipple procedure, the pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy technique is associated with shorter operation time and less intraoperative blood loss, requiring less blood transfusion. Post-operative complications, hospital mortality and survival do not differ between the two methods.[22][23][24]

Morbidity and mortality

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is considered, by any standard, to be a major surgical procedure.

Many studies have shown that hospitals where a given operation is performed more frequently have better overall results (especially in the case of more complex procedures, such as pancreaticoduodenectomy). A frequently cited study published in The New England Journal of Medicine found operative mortality rates to be four times higher (16.3 v. 3.8%) at low-volume (averaging less than one pancreaticoduodenectomy per year) hospitals than at high-volume (16 or more per year) hospitals. Even at high-volume hospitals, morbidity has been found to vary by a factor of almost four depending on the number of times the surgeon has previously performed the procedure.[25] de Wilde et al. have reported statistically significant mortality reductions concurrent with centralization of the procedure in the Netherlands.[26]

One study reported actual risk to be 2.4 times greater than the risk reported in the medical literature, with additional variation by type of institution.[27]

Postoperative complications

Three of the most common post-operative complications are delayed gastric emptying, bile leak, and pancreatic leak. Delayed gastric emptying, normally defined as an inability to tolerate a regular diet by the end of the first post-op week and the requirement for nasogastric tube placement, occurs in approximately 17% of operations.[28][29] During the surgery, a new biliary connection (normally a choledochal-jejunal anastamosis connecting the common bile duct and jejunum) is made. This new connection may leak in 1–2% of operations. As this complication is fairly common, it is normal in this procedure for the surgeon to leave a drain in place at the end.[30] This allows for detection of a bile leak via elevated bilirubin in the fluid drained. Pancreatic leak or pancreatic fistula, defined as fluid drained after postoperative day 3 that has an amylase content greater than or equal to 3 times the upper limit of normal, occurs in 5–10% of operations,[31][32] although changes in the definition of fistula may now include a much larger proportion of patients (upwards of 40%).[33]

Recovery after surgery

Immediately after surgery, patients are monitored for return of bowel function and appropriate closed-suction drainage of the abdomen.

Return of bowel function

Ileus, which refers to functional obstruction or aperistalsis of the intestine, is a physiologic response to abdominal surgery, including the Whipple procedure.[34] While post-operative ileus is typically self-limited, prolonged post-operative ileus occurs when patients develop nausea, abdominal distention, pain or intolerance of food by mouth.[35] Various measures are taken in the immediate post-operative period to minimize prolonged post-operative ileus. A nasogastric tube is typically maintained to suction, to drain gastric and intestinal contents. Ambulation is encouraged to stimulate return of bowel function. Use of opioid medications, which interfere with intestinal motility, is limited.[36]

History

This procedure was originally described by Alessandro Codivilla, an Italian surgeon, in 1898.[37] The first resection for a periampullary cancer was performed by the German surgeon Walther Kausch in 1909 and described by him in 1912. It is often called Whipple's procedure or the Whipple procedure, after the American surgeon Allen Whipple who devised an improved version of the surgery in 1935 while at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York[38] and subsequently came up with multiple refinements to his technique.

Nomenclature

Fingerhut et al. argue that while the terms pancreatoduodenectomy and pancreaticoduodenectomy are often used interchangeably in the medical literature, scrutinizing their etymology yields different definitions for the two terms.[1] As a result, the authors prefer pancreatoduodenectomy over pancreaticoduodenectomy for the name of this procedure, as strictly speaking pancreaticoduodenectomy should refer to the resection of the duodenum and pancreatic duct rather than the pancreas itself.[1]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Fingerhut A, Vassiliu P, Dervenis C, Alexakis N, Leandros E (September 2007). "What is in a word: Pancreatoduodenectomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy?". Surgery. 142 (3): 428–429. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2007.06.002. PMID 17723902.

- ^ a b c Reber H (24 October 2016). "Surgical resection of lesions of the head of the pancreas". UpToDate. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ Sun J, Yang Y, Wang X, Yu Z, Zhang T, Song J, et al. (October 2014). "Meta-analysis of the efficacies of extended and standard pancreatoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas". World Journal of Surgery. 38 (10): 2708–2715. doi:10.1007/s00268-014-2633-9. PMID 24912627. S2CID 20402342.

- ^ a b Cameron JL, Riall TS, Coleman J, Belcher KA (July 2006). "One thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies". Annals of Surgery. 244 (1): 10–15. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000217673.04165.ea. PMC 1570590. PMID 16794383.

- ^ [1], Lillemoe K, Loehrer A. Whipple procedure for multiple endocrine neoplasia of the pancreas. J Med Ins. 2018;2018(16). doi:https://doi.org/10.24296/jomi/16.

- ^ Clancy TE (August 2015). "Surgery for Pancreatic Cancer". Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 29 (4): 701–716. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2015.04.001. PMID 26226905.

- ^ O Kane GM, Knox JJ (2017-11-16). "Locally advanced pancreatic cancer: An emerging entity". Current Problems in Cancer. 42 (1): 12–25. doi:10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2017.10.006. PMID 29153290.

- ^ Wolff RA (February 2018). "Adjuvant or Neoadjuvant Therapy in the Treatment in Pancreatic Malignancies: Where Are We?". The Surgical Clinics of North America. 98 (1): 95–111. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2017.09.009. PMID 29191281.

- ^ Pugalenthi A, Protic M, Gonen M, Kingham TP, Angelica MI, Dematteo RP, et al. (February 2016). "Postoperative complications and overall survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma". Journal of Surgical Oncology. 113 (2): 188–193. doi:10.1002/jso.24125. PMC 4830358. PMID 26678349.

- ^ a b "Periampullary Cancer: Symptoms, Staging & Treatment | Dr. Nikhil Agrawal". Dr.Nikhil Agrawal. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ Tsuchikawa T, Hirano S, Okamura K, Matsumoto J, Tamoto E, Murakami S, et al. (March 2015). "Advances in the surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma". Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 9 (3): 369–374. doi:10.1586/17474124.2015.960393. PMID 25256146. S2CID 39664698.

- ^ Zhao X, Cui N, Wang X, Cui Y (March 2017). "Surgical strategies in the treatment of chronic pancreatitis: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Medicine. 96 (9): e6220. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006220. PMC 5340451. PMID 28248878.

- ^ Gurusamy KS, Lusuku C, Halkias C, Davidson BR (February 2016). "Duodenum-preserving pancreatic resection versus pancreaticoduodenectomy for chronic pancreatitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD011521. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011521.pub2. PMC 8278566. PMID 26837472.

- ^ van der Wilden GM, Yeh D, Hwabejire JO, Klein EN, Fagenholz PJ, King DR, et al. (February 2014). "Trauma Whipple: do or don't after severe pancreaticoduodenal injuries? An analysis of the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB)". World Journal of Surgery. 38 (2): 335–340. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-2257-5. PMID 24121363. S2CID 206947730.

- ^ Gulla A, Tan WP, Pucci MJ, Dambrauskas Z, Rosato EL, Kaulback KR, et al. (January 2014). "Emergent pancreaticoduodenectomy: a dual institution experience and review of the literature". The Journal of Surgical Research. 186 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2013.07.057. PMID 24011528.

- ^ "Pancreatic Cancer Stages". Cancer.org. American Cancer Society. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Zakharova, OP; Karmazanovsky, GG; Egorov, VI (27 May 2012). "Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Outstanding problems". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 4 (5): 104–13. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v4.i5.104. PMC 3364335. PMID 22655124.

- ^ D'Cruz JR, Misra S, Shamsudeen S (2023). "Pancreaticoduodenectomy". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32809582. Retrieved 2023-07-29.

- ^ Testini M, Regina G, Todisco C, Verzillo F, Di Venere B, Nacchiero M (September 1998). "An unusual complication resulting from surgical treatment of periampullary tumours". Panminerva Medica. 40 (3): 219–222. PMID 9785921.

- ^ Hüttner FJ, Fitzmaurice C, Schwarzer G, Seiler CM, Antes G, Büchler MW, Diener MK (February 2016). "Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (pp Whipple) versus pancreaticoduodenectomy (classic Whipple) for surgical treatment of periampullary and pancreatic carcinoma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (2): CD006053. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006053.pub6. PMC 4356182. PMID 26905229.

- ^ a b Michalski CW, Weitz J, Büchler MW (September 2007). "Surgery insight: surgical management of pancreatic cancer". Nature Clinical Practice. Oncology. 4 (9): 526–535. doi:10.1038/ncponc0925. PMID 17728711. S2CID 1436015.

- ^ Karanicolas PJ, Davies E, Kunz R, Briel M, Koka HP, Payne DM, et al. (June 2007). "The pylorus: take it or leave it? Systematic review and meta-analysis of pylorus-preserving versus standard whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary cancer". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 14 (6): 1825–1834. doi:10.1245/s10434-006-9330-3. PMID 17342566. S2CID 23001824.

- ^ Diener MK, Knaebel HP, Heukaufer C, Antes G, Büchler MW, Seiler CM (February 2007). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of pylorus-preserving versus classical pancreaticoduodenectomy for surgical treatment of periampullary and pancreatic carcinoma". Annals of Surgery. 245 (2): 187–200. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000242711.74502.a9. PMC 1876989. PMID 17245171.

- ^ Iqbal N, Lovegrove RE, Tilney HS, Abraham AT, Bhattacharya S, Tekkis PP, Kocher HM (November 2008). "A comparison of pancreaticoduodenectomy with pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis of 2822 patients". European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 34 (11): 1237–1245. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2007.12.004. PMID 18242943.

- ^ "The Whipple Procedure". Pri-Med Patient Education Center. Harvard Health Publications. 2009. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011.

- ^ de Wilde RF, Besselink MG, van der Tweel I, de Hingh IH, van Eijck CH, Dejong CH, et al. (March 2012). "Impact of nationwide centralization of pancreaticoduodenectomy on hospital mortality". The British Journal of Surgery. 99 (3): 404–410. doi:10.1002/bjs.8664. PMID 22237731. S2CID 11120876.

- ^ Syin D, Woreta T, Chang DC, Cameron JL, Pronovost PJ, Makary MA (November 2007). "Publication bias in surgery: implications for informed consent". The Journal of Surgical Research. 143 (1): 88–93. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2007.03.035. PMID 17950077.

- ^ Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, et al. (November 2007). "Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS)". Surgery. 142 (5): 761–768. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2007.05.005. PMID 17981197.

- ^ Traverso LW, Hashimoto Y (2008). "Delayed gastric emptying: the state of the highest level of evidence". Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 15 (3): 262–269. doi:10.1007/s00534-007-1304-8. PMID 18535763.

- ^ Emekli E, Gündoğdu E (2020). "Computed tomography evaluation of early post-operative complications of the Whipple procedure". Polish Journal of Radiology. 85 (1): e104–e109. doi:10.5114/pjr.2020.93399. PMC 7247017. PMID 32467744.

- ^ Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. (July 2005). "Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition". Surgery. 138 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. PMID 16003309.

- ^ Cullen JJ, Sarr MG, Ilstrup DM (October 1994). "Pancreatic anastomotic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, significance, and management". American Journal of Surgery. 168 (4): 295–298. doi:10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80151-5. PMID 7524375.

- ^ Tan WJ, Kow AW, Liau KH (August 2011). "Moving towards the New International Study Group for Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definitions in pancreaticoduodenectomy: a comparison between the old and new". HPB. 13 (8): 566–572. doi:10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00336.x. PMC 3163279. PMID 21762300.

- ^ Sugawara K, Kawaguchi Y, Nomura Y, Suka Y, Kawasaki K, Uemura Y, et al. (March 2018). "Perioperative Factors Predicting Prolonged Postoperative Ileus After Major Abdominal Surgery". Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 22 (3): 508–515. doi:10.1007/s11605-017-3622-8. PMID 29119528. S2CID 3703174.

- ^ Livingston EH, Passaro EP (January 1990). "Postoperative ileus". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 35 (1): 121–132. doi:10.1007/bf01537233. PMID 2403907. S2CID 27117157.

- ^ Vather R, Bissett I (May 2013). "Management of prolonged post-operative ileus: evidence-based recommendations". ANZ Journal of Surgery. 83 (5): 319–324. doi:10.1111/ans.12102. PMID 23418987. S2CID 28400301.

- ^ Schnelldorfer T, Sarr MG (December 2009). "Alessandro Codivilla and the first pancreatoduodenectomy". Archives of Surgery. 144 (12): 1179–1184. doi:10.1001/archsurg.2009.219. PMID 20026839.

- ^ synd/3492 at Who Named It?

External links

- Toronto Whipple Clinical Pathway Education App – Open access App for patient and caregiver education

- The Toronto Video Atlas of Liver, Pancreas and Transplant Surgery – Video of Whipple procedure

- The Toronto Video Atlas of Liver, Pancreas and Transplant Surgery Patient Education Module – Patient and Family Education video for the Whipple procedure

- "Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy: a historical comment Adrian O'Sullivan" – The original description of Whipple's operation together with a modern commentary