Pamplona

Pamplona Iruña (Basque) Pampeluna | |

|---|---|

| Pamplona / Iruña | |

| Coordinates: 42°49′N 1°39′W / 42.817°N 1.650°W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Autonomous Community | Navarre |

| Comarca | Cuenca de Pamplona |

| Founded | 74 BC |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Joseba Asirón (EH Bildu) |

| Area | |

| 25.14 km2 (9.71 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 450 m (1,480 ft) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

| 209,672 | |

| • Density | 8,300/km2 (22,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 319,208 |

| population-ranking: 29th (municipality); 23rd (metro area) | |

| GDP | |

| • Metro | €18.942 billion (2020) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Patron saint |

|

| Website | www |

Pamplona (Spanish pronunciation: [pamˈplona] ⓘ; Basque: Iruña [iɾuɲa]),[a] historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain.

Lying at near 450 m (1,480 ft) above sea level,[5] the city (and the wider Cuenca de Pamplona) is located on the flood plain of the Arga river,[6] a second-order tributary of the Ebro. Precipitation-wise, it is located in a transitional location between the rainy Atlantic northern façade of the Iberian Peninsula and its drier inland. Early population in the settlement traces back to the late Bronze to early Iron Age,[7] even if the traditional inception date refers to the foundation of Pompaelo by Pompey during the Sertorian Wars circa 75 BC.[8] During Visigothic rule Pamplona became an episcopal see, serving as a staging ground for the Christianization of the area.[9] It later became one of the capitals of the Kingdom of Pamplona/Navarre.

The city is famous worldwide for the running of the bulls during the San Fermín festival, which is held annually from 6 July to 14 July. This festival was brought to literary renown with the 1926 publication of Ernest Hemingway's novel The Sun Also Rises. It is also home to Osasuna, the only Navarrese football club to have ever played in the Spanish top division.

History

Foundation and Roman times

In the winter of 75–74 BC, the area served as a camp for the Roman general Pompey in the war against Sertorius. He is considered to be the founder of Pompaelo, "as if Pompeiopolis" in Strabo's words,[10] which became Pamplona, in modern Spanish. However, in later times, it has been discovered to be the chief town of the Vascones. They called it Iruña, translating to 'the city'. Roman Pompaelo was located in the province of Hispania Tarraconensis, on the Ab Asturica Burdigalam, the road from Burdigala (modern Bordeaux) to Asturica (modern Astorga);[11] it was a civitas stipendiaria in the jurisdiction of the conventus of Caesaraugusta (modern Zaragoza).[12]

Early Middle Ages

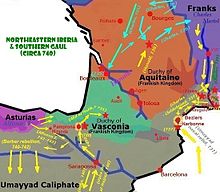

During the Germanic invasions of 409 and later as a result of Rechiar's ravaging, Pamplona went through much disruption and destruction,[13] starting a cycle of general decline along with other towns across the Basque territory, but managing to keep some sort of urban life.[14] During the Visigothic period (fifth to eighth centuries), Pamplona alternated between self-rule, Visigoth domination or Frankish suzerainty in the Duchy of Vasconia (Councils of Toledo unattended by several Pamplonese bishops between 589 and 684). In 466 to 472, Pamplona was conquered by the Visigoth count Gauteric,[15] but they seemed to abandon the restless position soon, struggling as the Visigoth kingdom was to survive and rearrange its lands after their defeats in Gaul. During the beginning of the sixth century, Pamplona probably stuck to an unstable self-rule, but in 541, Pamplona, along with other northern Iberian cities, was raided by the Franks.

Around 581, the Visigoth king Liuvigild overcame the Basques, seized Pamplona, and founded in the town of Victoriacum.[16] Despite the legend citing Saint Fermin as the first bishop of Pamplona and his baptising of 40,000 pagan inhabitants in just three days, the first reliable accounts of a bishop date from 589, when bishop Liliolus attended the Third Council of Toledo. After 684 and 693, a bishop called Opilano is mentioned again in 829, followed by Wiliesind and a certain Jimenez from 880 to 890. Even in the 10th century, important gaps are found in bishop succession, which is recorded unbroken only after 1005.[17]

At the time of the Umayyad invasion in 711, the Visigothic king Roderic was fighting the Basques in Pamplona and had to turn his attention to the new enemy coming from the south. By 714–16, the Umayyad troops had reached the Basque-held Pamplona, with the town submitting apparently after a treaty was brokered between the inhabitants and the Arab military commanders.[18] The position was then garrisoned by Berbers, who were stationed on the outside of the actual fortress, and established the cemetery unearthed not long ago at the Castle Square (Plaza del Castillo). During the following years, the Basques south of the Pyrenees do not seem to have shown much resistance to the Moorish thrust, and Pamplona may even have flourished as a launching point and centre of assembly for their expeditions into Gascony.[19] In 740, the Wali (governor) Uqba ibn al-Hajjaj imposed direct central Cordovan discipline on the city. In 755, though, the last governor of Al-Andalus, Yusuf al Fihri, sent an expedition north to quash Basque unrest near Pamplona, resulting in the defeat of the Arab army.[20]

From 755 until 781, Pamplona remained autonomous, probably relying on regional alliances. Although sources are not clear, it seems apparent that in 778, the town was in hands of a Basque local or a Muslim rebel faction loyal to the Franks at the moment of Charlemagne's crossing of the Pyrenees to the south. However, on his way back from the failed expedition to Saragossa in August, the walls and probably the town were destroyed by Charlemagne (ahead of the Frankish defeat in the famous Battle of Roncevaux), out of fear that the anti-Frankish party strong in the town might use the position against him. After Abd al-Rahman I's conquest, Pamplona and its hinterland remained in a state of shaky balance between Franks, regional Andalusian lords and central Cordovan rule, all of whom proved unable to permanently secure dominance over the Basque region. To a considerable extent, that alternation reflected the internal struggles of the Basque warrior nobility.

After the Frankish defeat at Roncevaux (778), Pamplona switched again to Cordovan rule, after Abd-al-Rahman's expedition captured the stronghold in 781. A wali or governor was imposed, Mutarrif ibn-Musa (a Banu-Qasi) up to the 799 rebellion. In that year, the Pamplonese—possibly led by a certain Velasko—stirred against their governor, but later the inhabitants provided some support for the Banu Qasi Fortun ibn-Musa's uprising. This regional revolt was shortly after suppressed by the Cordovan emir Hisham I, who re-established order, but failed to retain his grip on the town, since the Pamplonese returned to Frankish suzerainty in 806.[21] A Muslim cemetery containing about 200 human remains mingled with Christian tombs was unearthed in 2003 at the Castle Square, bearing witness to an important Muslim presence in the city during this period, but further research was stopped by the destruction of this and other historic evidence as decided by the city council, headed by mayor Yolanda Barcina.[22][23]

Following a failed expedition to the town led by Louis the Pious around 812, allegiance to the Franks collapsed after Enecco Arista rose to prominence. Moreover, he was crowned as king of Pamplona in 824, when the Banu Qasi and he gained momentum in the wake of their victorious second battle of Roncevaux. The new kingdom, inextricably linked to the Banu Qasi of Tudela, strengthened its independence from the weakened Frankish empire and Cordoban emirate.

During this period, Pamplona was not properly a town, but just a kind of fortress. In 924, Cordovan sources describe Pamplona as "not being especially gifted by nature", with its inhabitants being poor, not eating enough, and dedicated to banditry. They are reported to speak Basque for the most part, which "makes them incomprehensible".[24] On the 24 July, after Christian troops and citizens fled, troops from Cordova sacked Pamplona, destroying houses and buildings including its celebrated church.[25]

The town only regained its urban and human shape after the end of raids by Vikings and Andalusians on the province. Especially after 1083, traffic on the Way of St James brought prosperity and new cultures via travelers from north of the Pyrenees.[26]

Three boroughs and one city

From the 11th century, reviving economic development allowed Pamplona to recover its urban life. The bishops of Pamplona recovered their ecclesiastical leading role; during the previous centuries, isolated monasteries, especially Leyre, had actually held the religious authority. The pilgrimages to Santiago de Compostela contributed to the revival of the commercial and cultural exchanges with Christian Europe beyond the Pyrenees. In the 12th century, the city enlarged with two new separate burgos (independent boroughs): San Cernín (Saint Saturnin) and San Nicolás; the population of local Navarrese mainly confined to the original urban nucleus, the Navarrería, was swelled by Occitan merchants and artisans.

The boroughs showed very distinct features both socially and culturally, and were almost always engaged in quarrels among themselves. The most dramatic episode was the burning of the borough San Nicolás in 1258 and the destruction of the Navarrería by the other two boroughs and the massacre of its population in 1276. The site was abandoned for nearly 50 years. With regards to the outer defence walls of the city, the southern side was the weakest flank of the city, and the Navarrese king Louis I built a castle in the early 14th century in the site known today as Plaza del Castillo (Castle Square).

Eventually, King Charles III decreed the unification of the boroughs in a single city in 1423. The feuds between boroughs had been partly ignited by disputes over the use of the gulf dividing the three boroughs, so after Charles III's unification, the gulf was filled and on its site a common space laid out on the present-day city hall. The walls dividing the boroughs were demolished.

During the late 15th century, Pamplona bore witness to power struggles between the Beaumont and Agramont confederacies and external military interventions. Several times, the stronghold was taken over by different factions and foreign forces, like the ones sent by Ferdinand II of Aragon. Queen Catherine I was a minor and often absent from Pamplona, but eventually she married John III in 1494, an event celebrated with joy in the city. However, Navarre continued divided.

Historically, a Jewish community existed in Pamplona. The first documentation of Jews in Pamplona dates to 958, when Hasdai Ibn Shaprut visited Pamplona on a diplomatic mission to meet with Sancho I.[27] The Jews of Pamplona had an independent court system which enforced the Jewish system of halacha, or religious laws. In 1498, the Jewish population was either expelled or forced to convert to Christianity.[28]

- The Monumento a los Caídos, Francoist memorial, subject to debate about its potential demolition

- Estafeta Street

- Seconds before the beginning of the San Fermín Festival - Town Hall Square: Everybody has a red handkerchief above their heads until a firework is exploded at 12 pm; putting it around their neck afterward.

A fortress-city

After the 1512 conquest and annexation of Navarre to Spain, Pamplona remained as capital of the semiautonomous kingdom of Navarre, which preserved its own (reformed) institutions and laws. Pamplona became a Castilian-Spanish outpost at the foot of the western Pyrenees. After the Castilian conquest, king Ferdinand V ordered in 1513 the demolition and removal of the medieval castle and the city's monasteries, as well as the building of a new castle in a very close place. In 1530, with Navarre under Spanish military occupation, the Castilian viceroy was still expecting a "French invasion", and in fear of a possible revolt of the city dwellers, he requested an additional 1,000-strong force from what he called "healthy land", i.e. Castile, besides the 1,000 stationed already in Navarre.[29]

The progress of artillery demanded a complete renewal of the fortified system. Starting in 1569, King Philip II built the fortifications at Pamplona, to designs by Giovan Giacomo Paleari and Vespasiano Gonzaga. The citadel in the south of the town is a pentagonal star fort. Phillip had the city bounded by walls that made it almost a regular pentagon. The modernization of the walls was intended mainly to keep locals in check[30] and strengthen the outpost Pamplona had become on the border with independent Navarre, a close ally of France. The walls that exist today date from the late 16th to 18th centuries.

During the 18th century, Pamplona was considerably beautified and its urban services improved. A continuous water supply was established and the streets were paved, among many other enhancements. Rich aristocrats and businessmen also built their mansions. In the 19th century, this fortress-city played a key role in several wars in which Spain was involved.

During the Peninsular War of the Napoleonic Wars, French troops occupied the city - by launching a coup de main (surprise attack) and seized the city in 1808, and remained in it until the French forces were compelled to surrender on 31 October 1813 due to starvation, having been blockaded in the town for four months by the Spanish army under Enrique José O'Donnell.[31]: 334

During the Carlist Wars (1833–1839 and 1872–1876) Pamplona was each time controlled by the liberals, not just because the few liberals that lived in Navarre were mainly Pamplonese, but also because of the governmental control over the fortified city. Although Carlist rebels easily ruled the countryside, the government army had no problem in dominating the walled capital of Navarre. Nevertheless, during the last Carlist war, modern artillery operated by Carlists from surrounding mountains showed that the old walls would not be enough in the face of a stronger enemy. Thus, the government decided to build a fort on the top of mount San Cristóbal, just 3 km (1.9 mi) north of Pamplona.

Due to its military role, the city could not grow outside its walled belt. Furthermore, building in the closest area to the walls was banned to avoid any advantage for a besieger; thus the city could only grow by increasing its housing density. Higher and narrower houses were built and courtyards gradually disappeared. During the 19th century, road transportation improved, and the railway came in 1860. Nevertheless, industry in Pamplona and Navarre as a whole was weak during the century of the Industrial Revolution. Basically, no industrial development was feasible in such a constrained fortress-city.

After a slight modification of the star fort allowed an expansion of just six blocks in 1888, the First World War demonstrated that the fortified system of Pamplona was already obsolete. In 1915, the Army allowed the destruction of the walls and abolished the building ban in the city's surroundings. The southern side of the walls was destroyed and the other three remained as they did not hinder urban growth. The star fort continued to serve as a military facility until 1964, but just as a garrison.

Pamplona has in recent years taken great care to integrate and preserve its fortifications for modern use. In October 2014, working with the city of Bayonne, Pamplona hosts an international conference 'Fortified Heritage: Management and Sustainable Development', the website is in English, French, and Spanish.[32]

Available on a growing website are two free e-books, with copious colour photographs, on Pamplona's fortifications. Published in 2011 is 'Five living centuries of an impregnable fortress' about the city citadel[33] and 'A walk round the Pamplona fortifications'.[34]

Industrialization and modernization

Freed from its military function, Pamplona could lead the process of industrialization and modernization in which Navarre was involved during the 20th century, especially during its second half. The urban growth has been accompanied by the development of industry and services. Population growth has been the effect of an intense immigration process during the 1960s and 1970s: from the Navarrese countryside and from other less developed regions of Spain, mainly Castile and León and Andalusia. Since the 1990s the immigration is coming mainly from abroad.

Pamplona is listed as a city with one of the highest standards of living and quality of life in Spain.[35] Its industry rate is higher than the national average,[citation needed] although it is threatened by delocalization. Crime statistics are lower than the national average but cost of living, especially housing, is considerably higher.[36] Thanks to its small size and an acceptable public transport service, there are no major transport problems.

Geography

Pamplona is located in the middle of Navarre in a rounded valley, known as the Basin of Pamplona, that links the mountainous north with the Ebro valley. It is 92 km (57 mi) from the city of San Sebastián, 117 km (73 mi) from Bilbao, 735 km (457 mi) from Paris, and 407 km (253 mi) from Madrid. The climate and landscape of the basin is a transition between those two main Navarrese geographical regions. Its central position at crossroads has served as a commercial link between those very different natural parts of Navarre. The historical centre of the city is on the left bank of the Arga River, a tributary of the Ebro. The city has developed on both sides of the river.

Climate

The climate of Pamplona is classified as an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfb)[37] with influences of a Mediterranean climate (Csb). Due to global warming and stronger summer heat waves in the 21st century, it is also on the boundary with a humid subtropical climate (Cfa). Precipitation patterns do not vary much over the course of the year, as is typical of marine climates, but both classifications are possible due to the Mediterranean patterns of somewhat drier summer months. Sunshine hours are typical for a location in Northern Spain, thus more similar to the oceanic coastal climate in nearby Basque locations than typical Spanish Mediterranean areas are, but rainfall is significantly lower than in Bilbao and especially San Sebastián, as well as the climate is harsher than in the northern coastal areas (colder winter lows, warmer summer highs) because of the altitude of 450 metres (1,480 ft) and its inland location.

| Climate data for Pamplona (1991–2020), extremes (1953–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.5 (67.1) |

23.6 (74.5) |

30 (86) |

29.6 (85.3) |

33.5 (92.3) |

38.5 (101.3) |

42.3 (108.1) |

40.6 (105.1) |

38.8 (101.8) |

30 (86) |

27 (81) |

20 (68) |

42.3 (108.1) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

18.1 (64.6) |

23.0 (73.4) |

25.8 (78.4) |

30.8 (87.4) |

35.1 (95.2) |

37.2 (99.0) |

37.1 (98.8) |

32.3 (90.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

15.8 (60.4) |

38.2 (100.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.5 (49.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

28.5 (83.3) |

29.2 (84.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

19.7 (67.5) |

13.2 (55.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

18.8 (65.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.7 (42.3) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.6 (70.9) |

22.1 (71.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

6.1 (43.0) |

13.3 (55.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

1.7 (35.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

5.8 (42.4) |

8.9 (48.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

14.6 (58.3) |

15.0 (59.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

2.3 (36.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −3.8 (25.2) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

0.3 (32.5) |

3.1 (37.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

9.8 (49.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.4 (43.5) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −12.4 (9.7) |

−15.2 (4.6) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

−15.2 (4.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 73.5 (2.89) |

56.8 (2.24) |

65.5 (2.58) |

72.1 (2.84) |

60.6 (2.39) |

55.2 (2.17) |

33.6 (1.32) |

32.9 (1.30) |

46.2 (1.82) |

66.8 (2.63) |

85.6 (3.37) |

71.2 (2.80) |

720.1 (28.35) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 10 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 103 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 114 | 130 | 191 | 204 | 237 | 259 | 302 | 287 | 230 | 179 | 117 | 104 | 2,354 |

| Source 1: Météo Climat[38] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Infoclimat [39] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Pamplona Airport(1981–2010), extremes (1953–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.5 (67.1) |

23.6 (74.5) |

30 (86) |

29.6 (85.3) |

33.5 (92.3) |

38.5 (101.3) |

40.2 (104.4) |

40.6 (105.1) |

38.8 (101.8) |

30 (86) |

27 (81) |

20 (68) |

40.6 (105.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.1 (48.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.4 (61.5) |

20.8 (69.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.3 (82.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

13.1 (55.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

6.3 (43.3) |

9.1 (48.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.1 (57.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

1.6 (34.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.3 (41.5) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.2 (57.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

4.8 (40.6) |

2.2 (36.0) |

7.4 (45.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −12.4 (9.7) |

−15.2 (4.6) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

−15.2 (4.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 62 (2.4) |

55 (2.2) |

59 (2.3) |

79 (3.1) |

65 (2.6) |

51 (2.0) |

38 (1.5) |

43 (1.7) |

49 (1.9) |

73 (2.9) |

80 (3.1) |

77 (3.0) |

734 (28.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 8.7 | 8 | 7.7 | 9.7 | 9.2 | 5.8 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 8.6 | 9.6 | 10.1 | 92.1 |

| Average snowy days | 2 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78 | 72 | 66 | 65 | 63 | 59 | 57 | 58 | 62 | 69 | 76 | 78 | 67 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 90.9 | 129.3 | 180.7 | 187.2 | 235.4 | 271.5 | 317.1 | 281.0 | 215.1 | 162.2 | 108.1 | 86.8 | 2,265.3 |

| Source 1: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[40] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[41] | |||||||||||||

Urbanism

Like many other European cities, it is very easy to distinguish what is so called the "old city" and the new neighborhoods. The oldest part of the old city is Navarrería, which corresponds with the Roman city. During the 12th century, the boroughs of Saint Sernin (San Saturnino or San Cernin) and Saint Nicholas (San Nicolás) were established. Charles III decreed the unification of the three places under a single municipality in 1423.

The city did not expand until the late 19th century. In 1888, a modest modification of the star fort was allowed, but it just permitted the building of six blocks. It was called the I Ensanche (literally, "first widening"). The southern walls were destroyed in 1915 and the II Ensanche ("second widening") was planned. Its plan followed the grid pattern model designed by Ildefons Cerdà for Barcelona. Its blocks were built between the 1920s and the 1950s. The prevailing housing model is apartment buildings of five to eight floors.

After the Civil War, three new zones of Pamplona began to grow: Rochapea, Milagrosa, and Chantrea. Only the last one was a planned neighborhood, the other two being disorderly growths. In 1957, the municipality designed the first general ordination plan for the city, which established the guidelines for further urban development. According to this, during the 1960s and 1970s saw the creation of new neighborhoods like San Juan, Iturrama, San Jorge, Etxabakoitz, and Orvina.

The urban expansion of Pamplona exceeded the administrative limits of the city and involved municipalities like Barañáin, Burlada, Villava, Ansoain, Berriozar, Noain or Huarte in a larger metropolitan area. During the 1980s and 1990s, new neighborhoods were born: Azpilagaña, Mendebaldea, and Mendillorri. Rochapea was profoundly renewed. The urban development of those new neighborhoods is very similar to other Spanish provincial capitals that experienced a similar aggressive economic development during the sixties and seventies. The urbanization of Pamplona, being from anterior designs, is not constrained by the grid plan. The apartment buildings are taller: never less than five floors and many taller than ten. Industry, which previously coexisted with housing, was moved to industrial parks (the oldest and the only one within municipal limits of Pamplona is Landaben).

In recent years, single-family house-predominant neighborhoods have grown in the metropolitan area: Zizur Mayor, Cizur Menor, Mutilva Alta, Mutilva Baja, Olaz, Esquíroz, Artica, Alzuza, Artiberri and Sarriguren. And new districts emerged like Buztintxuri, Lezkairu and Ripagaina, the latter two being still under construction. These new suburbs have more room for green areas and recreative parks.

Economy

Pamplona has shifted in a few decades from a little administrative and even rural town to a medium-size city of industry and services. The industry sector is diversified although the most important activity is related to automobile industry. Volkswagen manufactures Polo model in its factory of Landaben and there are many auxiliary industries that work for Volkswagen and other companies. Other remarkable industries are building materials, metalworking and food processing. Renewable energy technologies are also an increasing economic sector (wind turbine manufacturing and generation) and neighboring Sarriguren is the seat of the Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy, National Centre for Renewable Energies (CENER)[42] and of Acciona Energía.

Pamplona is the main commercial and services centre of Navarre. Its area of influence is not beyond the province, except for the University of Navarre and its teaching hospital, which provide private educational and health services nationwide.

Education and culture

The city is home to two universities: the above-mentioned University of Navarre, a corporate work of Opus Dei founded in 1952, which is ranked as the best private university in Spain,[43] and the Public University of Navarre, established by the Government of Navarre in 1987. There is also a local branch of the UNED (Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia).

The two most important museums in Pamplona are the Museo de Navarra, devoted to the archaeological and artistic heritage of Navarre, and the Museo Diocesano of religious art, located in the cathedral. Pamplona is the first Spanish city in the French way of the Way of Saint James.

Pamplona has hosted the Sarasate Violin International Competition biennially since 1991,[44] and the annual Punto de Vista International Documentary Film Festival, the most important Spanish documentary film festival, since 2004.

One of the more popular cultural expressions include the "Gigantes", which come out during festivals many times during the year. These are approximately 30-foot wooden statues that have a person inside that make them dance around the city. They represent each of the main continents of the world, including Europe, the Americas, Africa, and Asia.

Politics

Following the 2023 municipal election, the mayor of the city is Joseba Asiron (EH Bildu), also supported by the Socialist Party of Navarre, Geroa Bai, and Contigo Zurekin.[45]

Transportation

Pamplona is linked by motorways with neighbouring Zaragoza (1978), San Sebastián, Vitoria (1995) and Logroño (2006). Since 2007 buses use a new bus station in the city centre that replaces the old one (1934).

The airport (1972), operated by Aena and located in Noain, schedules several flights daily to Madrid and Barcelona.[46] There are railway (1861) links with Madrid, Zaragoza and northern Spain, operated by Renfe. High speed train link with Zaragoza, Madrid, and Barcelona was not expected until 2014. A new railway station will be built in the southern part of the city.

Within the city and surroundings there are also 23 daytime lines and 10 night lines of public buses, operated by TCC, the chartered company of the Mancomunidad de la Comarca de Pamplona.

Main sights

Several notable churches, most of its 16th- to 18th-century fortified system and other civil architecture buildings belong to the historic-artistic heritage of Pamplona.

Religious architecture

The most important religious building is the fourteenth century Gothic Cathedral, with an outstanding cloister and a Neoclassical façade. There are another two main Gothic churches in the old city: Saint Sernin and Saint Nicholas, both built during the thirteenth century. Two other Gothic churches were built during the sixteenth century: Saint Dominic and Saint Augustine. During the seventeenth and eighteenth century were built the Baroque chapels of Saint Fermin, in the church of Saint Lawrence, and of the Virgin of the Road (Virgen del Camino), in the church of Saint Sernin, the convents of the Augustinian Recollect nuns and the Carmelite friars, and the Saint Ignatius basilica in the place where he was injured in the battle and during the subsequent convalescence he decided to be a priest. The most remarkable twentieth century religious buildings are probably the new diocesan seminary (1931) and the classical-revival style memorial church (1942) to the Navarrese dead in the Nationalist side of the Civil War and that is used today as temporary exhibitions room.

- Pamplona Cathedral

- San Lorenzo Church

- San Ignacio Church

- San Saturnino Church

- San Nicolás Church

Military and civil architecture

From the prominent military past of Pamplona remain three of the four sides of the city walls and, with little modifications, the citadel or star fort. All the mediaeval structures were replaced and improved during 16th, 17th and 18th centuries in order to resist artillery sieges. Completely obsolete for modern warfare, they are used today as parks.

The oldest civil building today existing is a fourteenth-century house that was used as Cámara de Comptos (the court of auditors of the early modern autonomous kingdom of Navarre) from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. There are also several medieval bridges on the Arga: Santa Engracia, Miluce, Magdalena, and San Pedro. The medieval palace of Saint Peter, which was alternatively used by Navarrese kings and Pamplonese bishops, was used during the early modern age as the Viceroy's palace and later was the seat of the military governor of Navarre; from the time of the Civil War it was in ruins but was recently rebuilt to be used as the General Archive of Navarre.

The most outstanding Baroque civil architecture is from the eighteenth century: town hall, episcopal palace, Saint John the Baptist seminary, and the Rozalejo's, Ezpeleta's (today music school), Navarro-Tafalla's (today, the local office of PNV), and Guenduláin's (today, a hotel) mansions. The provincial government built its own Neoclassical palace, the so-called Palace of Navarre, during the nineteenth century.

Late nineteenth and early twentieth century Pamplonese architecture shows the tendencies that are fully developed in other more important Spanish cities: La Agrícola building (1912), several apartment buildings with some timid modernist ornamentation, etc. The most notable architect in twentieth century Pamplona was Víctor Eusa (1894–1990), whose designs were influenced by the European expressionism and other avant-garde movements.

Parks

Pamplona has many parks and green areas. The oldest is the Taconera park, whose early designs are from the seventeenth century. Taconera is today a romantic park, with wide pedestrian paths, parterres, and sculptures.

The Media Luna park was built as part of the II Ensanche and is intended to allow relaxing strolling and sightseeing over the northern part of the town.

After its demilitarization, the citadel (Ciudadela) and its surrounding area (Vuelta del Castillo) shifted into a park area with large lawns and modern sculptures.

The most remarkable parks of the new neighborhoods include the Yamaguchi park, between Iturrama and Ermitagaña, which includes a little Japanese garden as well as the Planetarium of Pamplona; the campus of the University of Navarre; the Parque del Mundo in Chantrea; and the Arga park.

Sports

CA Osasuna (Club Atlético Osasuna (Basque for "Health") is the local football team. Their home stadium is called El Sadar, known as Reyno de Navarra between 2005 and 2013 in exchange for the Government of Navarre's sponsorship. However there's another football club in the city called CD Pamplona, who always tends to be forgotten as it never reached the high levels of Osasuna.

Pamplona's bull ring was rebuilt in 1923. It seats 19,529 and is the third largest in the world, after the bull rings of Mexico City and Madrid.

Other sports with some of the top clubs in Pamplona include handball (Portland San Antonio, Europe's championship winner 2001), futsal (MRA Xota) and water polo (Larraina).

Pamplona's favourite son may well be Miguel Indurain, five time Tour de France winner. Former Arsenal goalkeeper Manuel Almunia is also from Pamplona.

The Movistar Team, the direct descendant of Indurain's Banesto team, is based in Egüés, a municipality in the metropolitan area of Pamplona.[47]

Pamplona is also home to the headquarters of the International Federation of Basque Pelota (FIPV). Basque pelota is principally practised in France, Spain, and North and South America, but also in other countries like Italy and Philippines.

Notable citizens

- Fermin (* 272; † 303)

- Martín de Rada, (1533–1578)

- Pablo de Sarasate (1844–1908), internationally renowned composer and violin player

- José Sanjurjo (1872–1936), army general

- Joaquín Beunza Redín (1872-1936), Carlist politician

- Víctor Pradera Larumbe (1873–1936), Carlist politician

- Ignacio Baleztena Ascárate (1887–1972), Carlist politician

- Luis Arellano Dihinx (1906–1969), Carlist politician

- Sabicas (1912–1990)

- Jaime del Burgo Torres (1912–2005), Carlist politician

- Alfredo Landa (1933–2013)

- Marysa Navarro (born 1934)

- Carlos Garaikoetxea (born 1938)

- Javier Rojo (born 1949)

- Serafín Zubiri (born 1964), singer

- Jon Andoni Goikoetxea (born 1965), Spain footballer

- Alberto Urroz (born 1965), classical pianist

- Cesar Palacios Chocarro (born 1974), Spain footballer

- Javier López Vallejo (born 1975), Spain footballer

- Francisco Puñal (born 1975), Spain footballer

- Tiko (born 1976), Spain footballer

- Manuel Almunia (born 1977), Spain footballer

- Jesús María Lacruz (born 1978), Spain footballer

- Gorka Iraizoz (born 1981), Spain footballer

- Miguel Flaño (born 1984), Spain footballer

- Javier Flaño (born 1984), Spain footballer

- Fernando Llorente (born 1985), Spain footballer

- María Hernández (born 1986), Spanish professional golfer

- Raúl García (born 1986), Spain footballer

- Nacho Monreal (born 1986), Spain footballer

- Abel Azcona (born 1988), Contemporary artist

- César Azpilicueta (born 1989), Spain footballer

- Carlota Ciganda (born 1990), Spanish professional golfer

- Iker Muniain (born 1992), Spain footballer

- Mikel Merino (born 1996), Spain U21 footballer

- Amaia Romero (born 1999), singer

- Nico Williams (Born 2002), Spain footballer

- Oihan Sancet (Born 2000), Spain footballer

- Javier Garro Barrio (1933 - 2003)

Twin towns and sister cities

Pamplona is twinned with the following cities:

Notes

- ^ Iruñea is the Basque name proposed by the Royal Academy of the Basque Language, but the Basque name recognized by the Government of Navarre is Iruña.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "William Smith". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "William Smith". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.- Collins, Roger (1990). The Basques. Cambridge, Mass.: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17565-2.

- ^ "Municipios: Pamplona/Iruña". Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ "Población total Pamplona/Iruña a 2 de enero de 2020" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ "Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by metropolitan regions". ec.europa.eu.

- ^ "Fiesta de San Fermín". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2016-08-07.

- ^ Cañada Palacio, Fernando (1999). "Pamplona S. XI-XII: El origen de los Burgos". El urbanismo de los estados cristianos peninsulares. Aguilar de Campoo: Centros de Estudios del Románico. p. 189. ISBN 84-89483-12-4.

- ^ Bescos, A; Camarasa, A.M. (1998). "Caracterización hidrologica del Río Arga (Navarra): El agua como recurso y como riesgo". Estudios Geográficos. 59 (232). Madrid: Editorial CSIC: 290. doi:10.3989/egeogr.1998.i232.609. hdl:10550/39751. S2CID 134630943.

- ^ Cañada Palacio 1999, p. 189.

- ^ Núñez Astrain, Luis (2003). El euskera arcaico: extensión y parentescos. Tafalla: Editorial Txapalarta. p. 75. ISBN 84-8136-300-6.

- ^ Cañada Palacio 1999, p. 191.

- ^ Ptolemy ii. 6. § 67; Strabo iii. § 161

- ^ Antonine Itinerary p. 455

- ^ Pliny the Elder iii. 3. s. 4.

- ^ Collins 1990, p.76

- ^ Collins 1990, p.102

- ^ Jurio, Jimeno (1995). Historia de Pamplona y de sus lenguas. Tafalla: Editorial Txalaparta. p. 35. ISBN 84-8136-017-1.

- ^ Jurio, Jimeno (1995). Historia de Pamplona y de sus lenguas. Editorial Txalaparta. p. 36. ISBN 84-8136-017-1.

- ^ Collins 1990, p.154

- ^ Collins 1990, p.116

- ^ Collins 1990, p.117

- ^ Collins 1990, p.119

- ^ Collins 1990, p.124

- ^ Rekalde, Angel (2014-01-08). "Las piedras de la plaza del Castillo". Noticias de Navarra. Pamplona. Archived from the original on 2014-08-18. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- ^ "El informe pericial de Aranzadi denuncia 'un expolio' arqueológico en la Plaza del Castillo". El País. 2002-02-16. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ^ Jimeno Aranguren, Roldan; Lopez-Mugartza Iriarte, J.C. (Ed.) (2004). Vascuence y Romance: Ebro-Garona, Un Espacio de Comunicación. Pamplona: Gobierno de Navarra / Nafarroako Gobernua. p. 179. ISBN 84-235-2506-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jurio, Jimeno (1995). Historia de Pamplona y de sus lenguas. Tafalla: Editorial Txalaparta. p. 64. ISBN 84-8136-017-1.

- ^ Jimeno Aranguren, Roldan; Lopez-Mugartza Iriarte, J.C. (Ed.) (2004). Vascuence y Romance: Ebro-Garona, Un Espacio de Comunicación. Pamplona: Gobierno de Navarra / Nafarroako Gobernua. p. 167. ISBN 84-235-2506-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Pamplona". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Singer, Isidore; Kayserling, Meyer. "PAMPLONA". The Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ [dead link]"200 años de la caída de la Ciudadela". Diario de Noticias. Archived from the original on November 17, 2011. Retrieved 2008-02-17. Article in Spanish

- ^ Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- ^ congress.fortiuspamplonabayonne.eu Archived 2014-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Citadel of Pamplona". 6 May 2014.

- ^ "San Bartolome Fort". 6 May 2014.

- ^ "Pamplona, Bilbao and Gijón, the Spanish cities with the best quality of life". El Mundo (in Spanish). 2007-06-21. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ^ (in Spanish) habitathumano.com Archived 2007-02-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Pamplona, Spain Climate Summary". Weatherbase. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ "Météo climat stats Moyennes 1991/2020 Espagne (page 3)" (in French). Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ "Climatologie de l'année à Pamplona/Noain" (in French). Infoclimat. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "Standard Climate Values for Pamplona". Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ "Extreme Climate Values for Pamplona". 13 July 2020.

- ^ (in Spanish) Cener.com

- ^ See University of Navarre, Notable rankings

- ^ "Sarasate Live!". sarasatelive.com. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ "Joseba Asiron (EH Bildu), nuevo alcalde de Pamplona". Ayuntamento de Pamplona / Iruñeko Udala (in Spanish). 28 December 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ (in Spanish) History of the Airport of Pamplona, by Aena Archived 23 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "2009 Riders and teams Database - Cyclingnews.com". Retrieved 2009-08-14.

- ^ "National Commission for Decentralised cooperation". Délégation pour l’Action Extérieure des Collectivités Territoriales (Ministère des Affaires étrangères) (in French). Archived from the original on 2013-10-08. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

Bibliography

External links

- Official website

(in Spanish)

(in Spanish)