Mandate for Palestine

| League of Nations – Mandate for Palestine and Transjordan Memorandum | |

|---|---|

British Command Paper 1785, December 1922, containing the Mandate for Palestine and the Transjordan memorandum | |

Whilst the Mandate for Palestine document covered both Mandatory Palestine (from 1920) and the Emirate of Transjordan (added in 1921), Transjordan was never part of Mandatory Palestine.[i][ii][iii][iv] | |

| Created | Mid-1919 – 22 July 1922 |

| Date effective | 29 September 1923 |

| Repealed | 15 May 1948 |

| Location | UNOG Library; ref.: C.529. M.314. 1922. VI. |

| Signatories | Council of the League of Nations |

| Purpose | Creation of the territories of Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan |

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordan – which had been part of the Ottoman Empire for four centuries – following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. The mandate was assigned to Britain by the San Remo conference in April 1920, after France's concession in the 1918 Clemenceau–Lloyd George Agreement of the previously agreed "international administration" of Palestine under the Sykes–Picot Agreement. Transjordan was added to the mandate after the Arab Kingdom in Damascus was toppled by the French in the Franco-Syrian War. Civil administration began in Palestine and Transjordan in July 1920 and April 1921, respectively, and the mandate was in force from 29 September 1923 to 15 May 1948 and to 25 May 1946 respectively.

The mandate document was based on Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations of 28 June 1919 and the Supreme Council of the Principal Allied Powers' San Remo Resolution of 25 April 1920. The objective of the mandates over former territories of Ottoman Empire was to provide "administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone". The border between Palestine and Transjordan was agreed in the final mandate document, and the approximate northern border with the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon was agreed in the Paulet–Newcombe Agreement of 23 December 1920.

In Palestine, the Mandate required Britain to put into effect the Balfour Declaration's "national home for the Jewish people" alongside the Palestinian Arabs, who composed the vast majority of the local population; this requirement and others, however, would not apply to the separate Arab emirate to be established in Transjordan. The British controlled Palestine for almost three decades, overseeing a succession of protests, riots and revolts between the Jewish and Palestinian Arab communities. During the Mandate, the area saw the rise of two nationalist movements: the Jews and the Palestinian Arabs. Intercommunal conflict in Mandatory Palestine ultimately produced the 1936–1939 Arab revolt and the 1944–1948 Jewish insurgency. The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was passed on 29 November 1947; this envisaged the creation of separate Jewish and Arab states operating under economic union, and with Jerusalem transferred to UN trusteeship. Two weeks later, Colonial Secretary Arthur Creech Jones announced that the British Mandate would end on 15 May 1948. On the last day of the Mandate, the Jewish community there issued the Israeli Declaration of Independence. After the failure of the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, the 1947–1949 Palestine war ended with Mandatory Palestine divided among Israel, the Jordanian annexation of the West Bank and the Egyptian All-Palestine Protectorate in the Gaza Strip.

Transjordan was added to the mandate following the Cairo Conference of March 1921, at which it was agreed that Abdullah bin Hussein would administer the territory under the auspices of the Palestine Mandate. Since the end of the war it had been administered from Damascus by a joint Arab-British military administration headed by Abdullah's younger brother Faisal, and then became a no man's land after the French defeated Faisal's army in July 1920 and the British initially chose to avoid a definite connection with Palestine. The addition of Transjordan was given legal form on 21 March 1921, when the British incorporated Article 25 into the Palestine Mandate. Article 25 was implemented via the 16 September 1922 Transjordan memorandum, which established a separate "Administration of Trans-Jordan" for the application of the Mandate under the general supervision of Great Britain. In April 1923, five months before the mandate came into force, Britain announced its intention to recognise an "independent Government" in Transjordan; this autonomy increased further under a 20 February 1928 treaty, and the state became fully independent with the Treaty of London of 22 March 1946.

Background

Commitment regarding the Jewish people: the Balfour Declaration

Immediately following their declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire in November 1914, the British War Cabinet began to consider the future of Palestine[1] (at the time, an Ottoman region with a small minority Jewish population).[2][3] By late 1917, in the lead-up to the Balfour Declaration, the wider war had reached a stalemate. Two of Britain's allies were not fully engaged, the United States had yet to suffer a casualty, and the Russians were in the midst of the October Revolution.[4][5] A stalemate in southern Palestine was broken by the Battle of Beersheba on 31 October 1917. The release of the Balfour Declaration was authorised by 31 October; the preceding Cabinet discussion had mentioned perceived propaganda benefits amongst the worldwide Jewish community for the Allied war effort.[6][7]

The British government issued the Declaration, a public statement announcing support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, on 2 November 1917. The opening words of the declaration represented the first public expression of support for Zionism by a major political power.[8] The term "national home" had no precedent in international law,[5] and was intentionally vague about whether a Jewish state was contemplated.[5] The intended boundaries of Palestine were not specified,[9] and the British government later confirmed that the words "in Palestine" meant that the Jewish national home was not intended to cover all of Palestine.[10][11][12] The second half of the declaration was added to satisfy opponents of the policy, who said that it would otherwise prejudice the position of the local population of Palestine and encourage antisemitism worldwide by (according to the presidents of the Conjoint Committee, David L. Alexander and Claude Montefiore in a letter to the Times) "stamping the Jews as strangers in their native lands".[13] The declaration called for safeguarding the civil and religious rights for the Palestinian Arabs, who composed the vast majority of the local population, and the rights of Jewish communities in any other country.[14]

The Balfour Declaration was subsequently incorporated into the Mandate for Palestine to put the declaration into effect.[15] Unlike the declaration itself, the Mandate was legally binding on the British government.[15]

Commitment regarding the Arab population: the McMahon–Hussein correspondence

Between July 1915 and March 1916, a series of ten letters were exchanged between Sharif Hussein bin Ali, the head of the Hashemite family that had ruled the Hejaz as vassals for almost a millennium, and Lieutenant Colonel Sir Henry McMahon, British High Commissioner to Egypt.[16] In the letters – particularly that of 24 October 1915 – the British government agreed to recognise Arab independence after the war in exchange for the Sharif of Mecca launching the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire.[17][18] Whilst there was some military value in the Arab manpower and local knowledge alongside the British Army, the primary reason for the arrangement was to counteract the Ottoman declaration of jihad ("holy war") against the Allies, and to maintain the support of the 70 million Muslims in British India (particularly those in the Indian Army that had been deployed in all major theatres of the wider war).[19]

The area of Arab independence was defined as "in the limits and boundaries proposed by the Sherif of Mecca", with the exclusion of a coastal area lying to the west of "the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo"; conflicting interpretations of this description caused great controversy in subsequent years. A particular dispute, which continues to the present,[20] was whether Palestine was part of the coastal exclusion.[20][v] At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George told his French counterpart Georges Clemenceau and the other allies that the McMahon-Hussein correspondence was a treaty obligation.[22][23]

Commitment to the French: the Sykes–Picot agreement

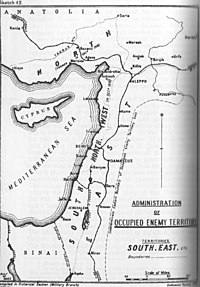

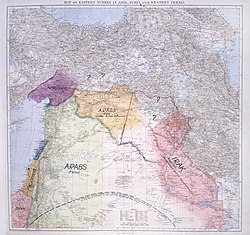

Around the same time, another secret treaty was negotiated between the United Kingdom and France (with assent by the Russian Empire and Italy) to define their mutually-agreed spheres of influence and control in an eventual partition of the Ottoman Empire. The primary negotiations leading to the agreement occurred between 23 November 1915 and 3 January 1916; on 3 January the British and French diplomats Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot initialled an agreed memorandum. The agreement was ratified by their respective governments on 9 and 16 May 1916. The agreement allocated to Britain control of present-day southern Israel and Palestine, Jordan and southern Iraq, and an additional small area including the ports of Haifa and Acre to allow access to the Mediterranean.[24] The Palestine region, with smaller boundaries than the later Mandatory Palestine, was to fall under an "international administration". The agreement was initially used as the basis for the 1918 Anglo–French Modus Vivendi, which provided a framework for the Occupied Enemy Territory Administration (OETA) in the Levant.[25]

Commitment to the League of Nations: the mandate system

The mandate system was created in the wake of World War I as a compromise between Woodrow Wilson's ideal of self-determination, set out in his Fourteen Points speech of January 1918, and the European powers' desire for gains for their empires.[26] It was established under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, entered into on 28 June 1919 as Part I of the Treaty of Versailles, and came into force on 10 January 1920 with the rest of the treaty. Article 22 was written two months before the signing of the peace treaty, before it was agreed exactly which communities, peoples, or territories would be covered by the three types of mandate set out in sub-paragraphs 4, 5, and 6 – Class A "formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire", Class B "of Central Africa" and Class C "South-West Africa and certain of the South Pacific Islands". The treaty was signed and the peace conference adjourned before a formal decision was made.[27]

Two governing principles formed the core of the mandate system: non-annexation of the territory and its administration as a "sacred trust of civilisation" to develop the territory for the benefit of its native people.[vi] The mandate system differed fundamentally from the protectorate system which preceded it, in that the mandatory power's obligations to the inhabitants of the territory were supervised by a third party: the League of Nations.[29] The mandates were to act as legal instruments containing the internationally agreed-upon terms for administering certain post-World War I territories on behalf of the League of Nations. These were of the nature of a treaty and a constitution, which contained minority-rights clauses that provided for the rights of petition and adjudication by the World Court.[30]

The process of establishing the mandates consisted of two phases: the formal removal of sovereignty of the state previously controlling the territory, followed by the transfer of mandatory powers to individual states among the Allied powers. According to the Council of the League of Nations meeting of August 1920, "draft mandates adopted by the Allied and Associated Powers would not be definitive until they had been considered and approved by the League ... the legal title held by the mandatory Power must be a double one: one conferred by the Principal Powers and the other conferred by the League of Nations."[31] Three steps were required to establish a mandate: "(1) The Principal Allied and Associated Powers confer a mandate on one of their number or on a third power; (2) the principal powers officially notify the council of the League of Nations that a certain power has been appointed mandatory for such a certain defined territory; and (3) the council of the League of Nations takes official cognisance of the appointment of the mandatory power and informs the latter that it [the council] considers it as invested with the mandate, and at the same time notifies it of the terms of the mandate, after ascertaining whether they are in conformance with the provisions of the covenant."[32][33]

Assignment to Britain

Palestine

Discussions about the assignment of the region's control began immediately after the war ended and continued at the Paris Peace Conference and the February 1920 Conference of London, and the assignment was made at the April 1920 San Remo conference. The Allied Supreme Council granted the mandates for Palestine and Mesopotamia to Britain, and those for Syria and Lebanon to France.[34]

In anticipation of the Peace Conference, the British devised a "Sharifian Solution" to "[make] straight all the tangle" of their various wartime commitments. This proposed that three sons of Sharif Hussein – who had since become King of the Hejaz, and his sons emirs (princes) – would be installed as kings of newly created countries across the region agreed between McMahon and Hussein in 1915. The Hashemite delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, led by Hussein's third son Emir Faisal, had been invited by the British to represent the Arabs at the conference; they had wanted Palestine to be part of the proposed Arab state, and later modified this request to an Arab state under a British mandate.[35] The delegation made two initial statements to the peace conference. The 1 January 1919 memorandum referred to the goal of "unit[ing] the Arabs eventually into one nation", defining the Arab regions as "from a line Alexandretta – Persia southward to the Indian Ocean". The 29 January memorandum[36] stipulated that "from the line Alexandretta – Diarbekr southward to the Indian Ocean" (with the boundaries of any new states) were "matters for arrangement between us, after the wishes of their respective inhabitants have been ascertained", in a reference to Woodrow Wilson's policy of self-determination.[36] In his 6 February 1919 presentation to the Paris Peace Conference, Faisal (speaking on behalf of King Hussein) asked for Arab independence or at least the right to choose the mandatory.[37][38] The Hashemites had fought with the British during the war, and received an annual subsidy from Britain; according to the confidential appendix to the August 1919 King-Crane Commission report, "the French resent the payment by the English to the Emir Faisal of a large monthly subsidy, which they claim covers a multitude of bribes, and enables the British to stand off and show clean hands while Arab agents do dirty work in their interest."[39][40]

The World Zionist Organization delegation to the Peace Conference – led by Chaim Weizmann, who had been the driving force behind the Balfour Declaration – also asked for a British mandate, asserting the "historic title of the Jewish people to Palestine".[41] The confidential appendix to the King-Crane Commission report noted that "The Jews are distinctly for Britain as mandatory power, because of the Balfour declaration."[39][40] The Zionists met with Faisal two weeks before the start of the conference in order to resolve their differences; the resulting Faisal–Weizmann Agreement was signed on 3 January 1919. Together with letter written by T. E. Lawrence in Faisal's name to Felix Frankfurter in March 1919, the agreement was used by the Zionist delegation to argue that their plans for Palestine had prior Arab approval;[42] however, the Zionists omitted Faisal's handwritten caveat that the agreement was conditional on Palestine being within the area of Arab independence.[a][42]

The French privately ceded Palestine and Mosul to the British in a December 1918 amendment to the Sykes–Picot Agreement; the amendment was finalised at a meeting in Deauville in September 1919.[43][vii] Matters were confirmed at the San Remo conference, which formally assigned the mandate for Palestine to the United Kingdom under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations. Although France required the continuation of its religious protectorate in Palestine, Italy and Great Britain opposed it. France lost the religious protectorate but, thanks to the Holy See, continued to enjoy liturgical honors in Mandatory Palestine until 1924 (when the honours were abolished).[45] As Weizmann reported to his WZO colleagues in London in May 1920,[b] the boundaries of the mandated territories were unspecified at San Remo and would "be determined by the Principal Allied Powers" at a later stage.[34][c][viii]

Addition of Transjordan

Under the terms of the 1915 McMahon-Hussein Correspondence and the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement, Transjordan was intended to become part of an Arab state or a confederation of Arab states. British forces retreated in spring 1918 from Transjordan after their first and second attacks on the territory,[50] indicating their political ideas about its future; they had intended the area to become part of an Arab Syrian state.[ix] The British subsequently defeated the Ottoman forces in Transjordan in late September 1918, just a few weeks before the Ottoman Empire's overall surrender.[52]

Transjordan was not mentioned during the 1920 discussions at San Remo, at which the Mandate for Palestine was awarded.[34][c] Britain and France agreed that the eastern border of Palestine would be the Jordan river as laid out in the Sykes–Picot Agreement.[x][53] That year, two principles emerged from the British government. The first was that the Palestine government would not extend east of the Jordan; the second was the government's chosen – albeit disputed – interpretation of the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence, which proposed that Transjordan be included in the area of "Arab independence" (excluding Palestine).[54][xi]

Regarding Faisal's Arab Kingdom of Syria, the French removed Hashim al-Atassi's newly proclaimed nationalist government and expelled King Faisal from Syria after the 23 July 1920 Battle of Maysalun. The French formed a new Damascus state after the battle, and refrained from extending their rule into the southern part of Faisal's domain; Transjordan became for a time a no-man's land[d] or, as Samuel put it, "politically derelict".[60][61]

There have been several complaints here that the political situation has not been dealt with with sufficient clarity, that the Mandate and boundaries questions were not mentioned. The Mandate is published and can now not be altered with one exception, which l will now explain. Transjordania, which in the first draft of the Mandate lay outside the scope of the Mandate, is now included. Article 25 of the Mandate which now lies before the League of Nations, contains this provision. Therewith, Mr. de Lieme, the question of the eastern boundaries is answered. The question will be still better answered when Cisjordania is so full that it overflows to Transjordania. The northern boundary is still unsatisfactory. We have made all representations, we have brought all the arguments to bear and the British Government has done everything in this connection. We have not received what we sought, and I regret to have to tell you this. The only thing we received was the concession to be allowed a voice in the discussion on the water rights. And now just a week ago, when the Administration in Palestine, under pressure from a few soldiers, wished to alter our boundaries we protested most strongly and confirmed the boundary along the lines that were agreed upon. That is not satisfactory, but with the forces at our disposal nothing else could be attained. So it is with the Mandate.

—Speech by World Zionist Organization president Chaim Weizmann[62][63]

The Congress notes with satisfaction that Transjordania, which the Jewish people has always regarded as an integral part of Erez Israel, is to be again incorporated into the mandated territory of Palestine. The Congress deplores that the question of the northern boundary of Erez Israel, despite all the efforts of the Executive, has not yet received a satisfactory solution.

—Congress Declaration, III. Boundaries.[64]

After the French occupation, the British suddenly wanted to know "what is the 'Syria' for which the French received a mandate at San Remo?" and "does it include Transjordania?".[65] British Foreign Minister Lord Curzon ultimately decided that it did not; Transjordan would remain independent, but in a close relationship with Palestine.[xii][66] On 6 August 1920, Curzon wrote to newly appointed High Commissioner Herbert Samuel about Transjordan: "I suggest that you should let it be known forthwith that in the area south of the Sykes–Picot line, we will not admit French authority and that our policy for this area to be independent but in closest relations with Palestine."[67][68] Samuel replied to Curzon, "After the fall of Damascus a fortnight ago ... Sheiks and tribes east of Jordan utterly dissatisfied with Shareefian Government most unlikely would accept revival",[69][70] and asked to put parts of Transjordan directly under his administrative control.[xiii] Two weeks later, on 21 August, Samuel visited Transjordan without authorisation from London;[e][72] at a meeting with 600 leaders in Salt, he announced the independence of the area from Damascus and its absorption into the mandate (proposing to quadruple the area under his control by tacit capitulation). Samuel assured his audience that Transjordan would not be merged with Palestine.[73][xiv] Curzon was in the process of reducing British military expenditures, and was unwilling to commit significant resources to an area considered of marginal strategic value.[71] He immediately repudiated Samuel's action, and sent (via the Foreign Office) a reiteration of his instructions to minimize the scope of British involvement in the area: "There must be no question of setting up any British administration in that area".[56][f] At the end of September 1920, Curzon instructed an Assistant Secretary at the Foreign Office, Robert Vansittart, to leave the eastern boundary of Palestine undefined and avoid "any definite connection" between Transjordan and Palestine to leave the way open for an Arab government in Transjordan.[g][77] Curzon subsequently wrote in February 1921, "I am very concerned about Transjordania ... Sir H.Samuel wants it as an annex of Palestine and an outlet for the Jews. Here I am against him."[78]

Abdullah, the brother of recently deposed King Faisal, marched into Ma'an at the head of an army of from 300 to 2,000 men on 21 November 1920.[79][80] Between then and the end of March 1921, Abdullah's army occupied all of Transjordan with some local support and no British opposition.[xv]

The Cairo Conference was convened on 12 March 1921 by Winston Churchill, then Britain's Colonial Secretary, and lasted until 30 March. It was intended to endorse an arrangement whereby Transjordan would be added to the Palestine mandate, with Abdullah as the emir under the authority of the High Commissioner, and with the condition that the Jewish National Home provisions of the Palestine mandate would not apply there.[ii] On the first day of the conference, the Middle East Department of the Colonial Office set out the situation of Transjordan in a memorandum.[86] On 21 March 1921, the Foreign and Colonial Office legal advisers decided to introduce Article 25 into the Palestine Mandate to allow for the addition of Transjordan.[h]

Drafting

The intended mandatory powers were required to submit written statements to the League of Nations during the Paris Peace Conference proposing the rules of administration in the mandated areas.[88] Drafting of the Palestine mandate began well before it was formally awarded at San Remo in April 1920, since it was evident after the end of the war that Britain was the favored power in the region.[xvii][i] The mandate had a number of drafts: the February 1919 Zionist proposals to the peace conference; a December 1919 compromise draft between the British and the Zionists; a June 1920 draft after Curzon's "watering down", and the December 1920 draft submitted to the League of Nations for comment.[xviii][90]

1919: Initial Zionist-British discussions

In the spring of 1919 the experts of the British Delegation of the Peace Conference in Paris opened informal discussions with representatives of the Zionist Organisation on the draft of a Mandate for Palestine. In the drafting and discussion in Paris Dr. Weizmann and Mr. Sokolow received valuable aid from the American Zionist Delegation. Towards the end of 1919 the British Delegation returned to London and as during the protracted negotiations Dr. Weizmann was often unavoidably absent in Palestine, and Mr. Sokolow in Paris, the work was carried on for some time by a temporary political committee, of which the Right Hon. Sir Herbert (then Mr.) Samuel, Dr. Jacobson, Dr. Feiwel, Mr. Sacher (of the Manchester Guardian), Mr. Landman, and Mr. Ben Cohen were the first members. The later stage of the drafting negotiations were carried on by a sub-comimittee consisting of Messrs. Sacher, Stein and Ben Cohen, formed specially for the Mandate and frontier questions. Drafts for the Mandate were prepared for the Zionist leaders by Professor Frankfurter and Mr. Gans. After consultation with various members of the Actions Committee and Palestinian [Jewish] delegates then in Paris, these proposals were handed to the British Delegation and were largely embodied in the first tentative draft, dated July 15th, 1919.

—Political Report, 2. The Palestine Mandate Negotiations, 1919–1921.[91][92][93]

The February 1919 Zionist Proposal to the Peace Conference was not discussed at the time, since the Allies' discussions were focused elsewhere. It was not until July 1919 that direct negotiations began between the British Foreign Office and the Zionists, after the production of a full draft mandate by the British. The British draft contained 29 articles, compared to the Zionist proposal's five articles.[xix] However, the Zionist Organisation Report stated that a draft was presented by the Zionist Organization to the British on 15 July 1919.[95]

Balfour authorised diplomatic secretary Eric Forbes Adam to begin negotiations with the Zionist Organization. On the Zionist side, the drafting was led by Ben Cohen on behalf of Weizmann, Felix Frankfurter and other Zionist leaders.[94][j] By December 1919, they had negotiated a "compromise" draft.[94]

1920: Curzon negotiations

Although Curzon took over from Balfour in October, he did not play an active role in the drafting until mid-March.[97] Israeli historian Dvorah Barzilay-Yegar notes that he was sent a copy of the December draft and commented, "... the Arabs are rather forgotten ...". When Curzon received the draft of 15 March 1920, he was "far more critical"[98] and objected to "... formulations that would imply recognition of any legal rights ..." (for example, that the British government would be "responsible for placing Palestine under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of a Jewish national home and the development of a self-governing Commonwealth ...").[99] Curzon insisted on revisions until the 10 June draft removed his objections;[100] the paragraph recognising the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine was removed from the preamble, and "self-governing commonwealth" was replaced by "self-governing institutions". "The recognition of the establishment of the Jewish National Home as the guiding principle in the execution of the Mandate" was omitted.[101]

After strenuous objection to the proposed changes, the statement concerning the historical connections of the Jews with Palestine was re-incorporated into the Mandate in December 1920.[95] The draft was submitted to the League of Nations on 7 December 1920,[101] and was published in the Times on 3 February 1921.[102]

1921: Transjordan article

The inclusion of Article 25 was approved by Curzon on 31 March 1921, and the revised final draft of the mandate was forwarded to the League of Nations on 22 July 1922.[87] Article 25 permitted the mandatory to "postpone or withhold application of such provisions of the mandate as he may consider inapplicable to the existing local conditions" in that region. The final text of the Mandate includes an Article 25, which states:

In the territories lying between the Jordan [river] and the eastern boundary of Palestine as ultimately determined, the Mandatory shall be entitled, with the consent of the Council of the League of Nations, to postpone or withhold application of such provisions of this mandate as he may consider inapplicable to the existing local conditions, and to make such provision for the administration of the territories as he may consider suitable to those conditions.[103]

The new article was intended to enable Britain "to set up an Arab administration and to withhold indefinitely the application of those clauses of the mandate which relate to the establishment of the National Home for the Jews", as explained in a Colonial Office letter three days later.[xx] This created two administrative areas – Palestine, under direct British rule, and the autonomous Emirate of Transjordan under the rule of the Hashemite family – in accordance with the British Government's amended interpretation of the 1915 McMahon–Hussein Correspondence.[104][k] At discussions in Jerusalem on 28 March, Churchill proposed his plan to Abdullah that Transjordan would be accepted into the mandatory area as an Arab country apart from Palestine and that it would be (initially for six months) under the nominal rule of the Emir Abdullah.[106] Churchill said that Transjordan would not form part of the Jewish national home to be established west of the River Jordan:[107][108][xxi][xxii]

Trans-Jordania would not be included in the present administrative system of Palestine, and therefore the Zionist clauses of the mandate would not apply. Hebrew would not be made an official language in Trans-Jordania and the local Government would not be expected to adopt any measures to promote Jewish immigration and colonisation.[111]

Abdullah's six-month trial was extended, and by the following summer he began to voice his impatience at the lack of formal confirmation.[xxiii]

1921–22: Palestinian Arab attempted involvement

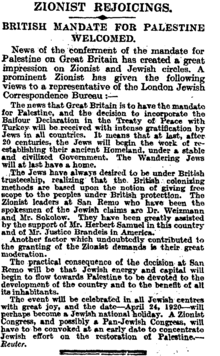

A New York Times report on 31 August 1921 on the Syrian–Palestinian Congress's message to the League of Nations "of the desire of the Syrian and Palestinian populations for complete independence outside of any power" |

The drafting was carried out with no input from any Arabs, despite the fact that their disagreement with the Balfour Declaration was well known.[xxiv] Palestinian political opposition began to organise in 1919 in the form of the Palestine Arab Congress, which formed from the local Muslim-Christian Associations. In March 1921, new British Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill came to the region to form British policy on the ground at the Cairo Conference. The leader of the Palestine congress, Musa al-Husayni, had tried to present the views of the executive committee in Cairo and (later) Jerusalem but was rebuffed both times.[114][115] In the summer of 1921, the 4th Palestine Arab Congress sent a delegation led by Musa al-Husayni to London to negotiate on behalf of the Muslim and Christian population.[l] On the way, the delegation held meetings with Pope Benedict XV and diplomats from the League of Nations in Geneva (where they also met Balfour, who was non-committal).[117] In London, they had three meetings with Winston Churchill in which they called for reconsideration of the Balfour Declaration, revocation of the Jewish National Home policy, an end to Jewish immigration and that Palestine should not be severed from its neighbours. All their demands were rejected, although they received encouragement from some Conservative Members of Parliament.[118][119][120]

Musa al-Husayni led a 1922 delegation to Ankara and then to the Lausanne Conference, where (after Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's victories against the Greek army in Turkey) the Treaty of Sèvres was about to be re-negotiated. The Palestinian delegation hoped that with Atatürk's support, they would be able to get the Balfour Declaration and mandate policy omitted from the new treaty. The delegation met with Turkey's lead negotiator, İsmet Pasha, who promised that "Turkey would insist upon the Arabs’ right of self-determination and ... the Palestinian delegation should be permitted to address the conference"; however, he avoided further meetings and other members of the Turkish delegation made clear their intention to "accept the post–World War I status quo".[121] During the negotiations, Ismet Pasha refused to recognise or accept the mandates;[m] although they were not referenced in the final treaty, it had no impact on the implementation of the mandate policy set in motion three years earlier.[121]

1922: Final amendments

Each of the principal Allied powers had a hand in drafting the proposed mandate, although some (including the United States) had not declared war on the Ottoman Empire and did not become members of the League of Nations.[124]

| Notable British drafts of the mandate[125][126][99][127] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Draft date | Negotiated between | Primary changes vs. prior version |

| 3 February 1919 Zionist Organization draft (Wikisource) |

Zionist Organization draft signed by Walter Rothschild, the Zionist Organization (Nahum Sokolow and Chaim Weizmann); the Zionist Organization of America (Julian Mack, Stephen S. Wise, Harry Friedenwald, Jacob de Haas, Mary Fels, Louis Robison and Bernard Flexner), and the Russian Zionist Organization (Israel Rosoff).[128] Submitted in February and reviewed by the British in April 1919.[94] | First version submitted to the Peace Conference. The draft contained only five clauses, of which the fifth contained five sub-clauses.[94] |

| 15 July 1919[92][93] British Foreign Office draft (Wikisource) |

British Foreign Office (Political Section) draft after discussion with the Zionist Organization, which later claimed that the proposals they put to the British were "largely embodied" in this draft.[92] | First official draft of the mandate[129] The preamble and 29 clauses adhered closely to the principles proposed by the Zionists.[94][93] Relevant changes included:

|

| 24 September 1919 Zionist Organization proposal (Wikisource) |

Zionist Organization counterproposal presented by Cohen to Forbes-Adam,[94] with amendments drafted by the Zionist "Actions Committee" in London in July and August[130] | Click here to see a comparison against the 15 July 1919 draft:

|

| 11 December 1919 "provisionally agreed upon between Zionist Organisation and British Delegation" (Wikisource) |

Provisional agreement reached after discussions in Paris in early December between Forbes-Adam and Herbert William Malkin for the British Foreign Office and Cohen for the Zionist Organization.[132][97] Forbes-Adam warned the Zionists that "this was not the final word".[97] |

|

| 10 June 1920 Submitted to the British Cabinet (Wikisource) |

Curzon | |

| 25 September 1920 Submitted to the British Cabinet (Wikisource) |

Curzon | |

| 7 December 1920 Submitted for review by the League of Nations (LoN) (Wikisource) |

Curzon | Comparison with the 25 September 1920 draft:

|

| 24 July 1922 Approved by the Council of the LoN (Wikisource) |

Council of the League of Nations; Transjordan change proposed by the British government at the March 1921 Cairo Conference; other changes proposed by other members of the Council of the League.[134] | Comparison with the 7 December 1920 draft:

|

Approvals

British Parliament

British public and government opinion became increasingly opposed to state support for Zionism, and even Sykes had begun to change his views in late 1918.[n] In February 1922 Churchill telegraphed Samuel, who had begun his role as High Commissioner for Palestine 18 months earlier, asking for cuts in expenditure and noting:

In both Houses of Parliament there is growing movement of hostility, against Zionist policy in Palestine, which will be stimulated by recent Northcliffe articles.[xxv] I do not attach undue importance to this movement, but it is increasingly difficult to meet the argument that it is unfair to ask the British taxpayer, already overwhelmed with taxation, to bear the cost of imposing on Palestine an unpopular policy.[137]

The House of Lords rejected a Palestine Mandate incorporating the Balfour Declaration by 60 votes to 25 after the June 1922 issuance of the Churchill White Paper, following a motion proposed by Lord Islington.[138][139] The vote was only symbolic, since it was subsequently overruled by a vote in the House of Commons after a tactical pivot and a number of promises by Churchill.[138][o][xxvi]

In February 1923, after a change in government, Cavendish laid the foundation for a secret review of Palestine policy in a lengthy memorandum to the Cabinet:

It would be idle to pretend that the Zionist policy is other than an unpopular one. It has been bitterly attacked in Parliament and is still being fiercely assailed in certain sections of the press. The ostensible grounds of attack are threefold:(1) the alleged violation of the McMahon pledges; (2) the injustice of imposing upon a country a policy to which the great majority of its inhabitants are opposed; and (3) the financial burden upon the British taxpayer ...[142]

His cover note asked for a statement of policy to be made as soon as possible, and for the cabinet to focus on three questions: (1) whether or not pledges to the Arabs conflict with the Balfour declaration; (2) if not, whether the new government should continue the policy set down by the old government in the 1922 White Paper and (3) if not, what alternative policy should be adopted.[143]

Stanley Baldwin, who took over as prime minister on 22 May 1923, set up a cabinet subcommittee in June 1923 whose terms of reference were to "examine Palestine policy afresh and to advise the full Cabinet whether Britain should remain in Palestine and whether if she remained, the pro-Zionist policy should be continued".[144] The Cabinet approved the report of this subcommittee on 31 July 1923; when presenting the subcommittee's report to the Cabinet, Curzon concluded that "wise or unwise, it is well nigh impossible for any government to extricate itself without a substantial sacrifice of consistency and self-respect, if not honour."[145] Describing it as "nothing short of remarkable", international law specialist Professor John B. Quigley noted that the government was admitting to itself that its support for Zionism had been prompted by considerations having nothing to do with the merits of Zionism or its consequences for Palestine.[146] Documents related to the 1923 reappraisal remained secret until the early 1970s.[147]

United States

The United States was not a member of the League of Nations. On 23 February 1921, two months after the draft mandates had been submitted to the League, the U.S. requested permission to comment before the mandate's consideration by the Council of the League of Nations; the Council agreed to the request a week later.[148] The discussions continued until 14 May 1922, when the U.S. government announced the terms of an agreement with the United Kingdom about the Palestine mandate.[148][149] The terms included a stipulation that "consent of the United States shall be obtained before any alteration is made in the text of the mandate".[150][151] Despite opposition from the State Department,[152] this was followed on 21 September 1922 by the Lodge–Fish Resolution, a congressional endorsement of the Balfour Declaration.[7][153][154]

On 3 December 1924 the U.S. signed the Palestine Mandate Convention, a bilateral treaty with Britain in which the United States "consents to the administration" (Article 1) and which dealt with eight issues of concern to the United States (including property rights and business interests).[155][156] The State Department prepared a report documenting its position on the mandate.[157]

Council of the League of Nations: Mandate

On 17 May 1922, in a discussion of the date on which the question of the Draft Mandate for Palestine should be placed on the agenda of the Council of the League of Nations, Lord Balfour informed the Council of his government's understanding of the role of the League in the creation of mandates:

[the] Mandates were not the creation of the League, and they could not in substance be altered by the League. The League's duties were confined to seeing that the specific and detailed terms of the mandates were in accordance with the decisions taken by the Allied and Associated Powers, and that in carrying out these mandates the Mandatory Powers should be under the supervision—not under the control—of the League. A mandate was a self-imposed limitation by the conquerors on the sovereignty which they exercised over the conquered territory.[158]

The Council of the League of Nations met between 19 and 24 July 1922 to approve the class A mandates for Palestine and Syria (minutes of the meetings can be read here). The Palestine mandate was approved on 22 July 1922 at a private meeting of the Council of the League of Nations at St. James Palace in London,[26] giving the British formal international recognition of the position they had held de facto in the region since the end of 1917 in Palestine and since 1920–21 in Transjordan.[26] The Council stated that the mandate was approved and would come into effect "automatically" when the dispute between France and Italy was resolved.[p] A public statement confirming this was made by the president of the council on 24 July.[q][161] With the Fascists gaining power in Italy in October 1922, new Italian Prime Minister Mussolini delayed the mandates' implementation.[xxvii] On 23 August 1923, the Turkish assembly in Ankara ratified the Treaty of Lausanne by 215 of 235 votes.[163][164][165][xxviii]

The Council of the League of Nations determined that the two mandates had come into effect at its 29 September 1923 meeting.[r][168] The dispute between France and Italy was resolved by the Turkish ratification.[xxix][170][104][xxx]

Council of the League of Nations: Transjordan memorandum

Shortly after the mandate's approval in July 1922, the Colonial Office prepared a memorandum to implement Article 25.[xxxi] On 16 September 1922, the League of Nations approved a British memorandum detailing its intended implementation of the clause excluding Transjordan from the articles related to Jewish settlement.[173][174][175] When the memorandum was submitted to the Council of the League of Nations, Balfour explained the background; according to the minutes, "Lord Balfour reminded his colleagues that Article 25 of the mandate for Palestine as approved by the Council in London on July 24th, 1922, provides that the territories in Palestine which lie east of the Jordan should be under a somewhat different regime from the rest of Palestine ... The British Government now merely proposed to carry out this article. It had always been part of the policy contemplated by the League and accepted by the British Government, and the latter now desired to carry it into effect. In pursuance of the policy, embodied in Article 25, Lord Balfour invited the Council to pass a series of resolutions which modified the mandate as regards those territories. The object of these resolutions was to withdraw from Trans-Jordania the special provisions which were intended to provide a national home for the Jews west of the Jordan."[175]

Turkey

Turkey was not a member of the League of Nations at the time of the negotiations; on the losing side of World War I, they did not join until 1932. Decisions about mandates over Ottoman territory made by the Allied Supreme Council at the San Remo conference were documented in the Treaty of Sèvres, which was signed on behalf of the Ottoman Empire and the Allies on 10 August 1920. The treaty was never ratified by the Ottoman government, however,[176][page needed][better source needed] because it required the agreement of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Atatürk expressed disdain for the treaty, and continued what was known as the Turkish War of Independence. The Conference of Lausanne began in November 1922, with the intention of negotiating a treaty to replace the failed Treaty of Sèvres. In the Treaty of Lausanne, signed on 24 July 1923, the Turkish government recognised the detachment of the regions south of the frontier agreed in the Treaty of Ankara (1921) and renounced its sovereignty over Palestine.[176][better source needed][page needed]

Key issues

National home for the Jewish people (Preamble and Articles 2, 4, 6, 7, 11)

According to the second paragraph of the mandate's preamble,

Whereas the Principal Allied Powers have also agreed that the Mandatory should be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 2nd, 1917, by the Government of His Britannic Majesty, and adopted by the said Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing should be done which might prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country ...[177]

Weizmann noted in his memoirs that he considered the most important part of the mandate, and the most difficult negotiation, the subsequent clause in the preamble which recognised "the historical connection of the Jews with Palestine".[s] Curzon and the Italian and French governments rejected early drafts of the mandate because the preamble had contained a passage which read, "Recognising, moreover, the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and the claim which this gives them to reconstitute it their national home..."[178] The Palestine Committee set up by the Foreign Office recommended that the reference to "the claim" be omitted. The Allies had already noted the historical connection in the Treaty of Sèvres, but had not acknowledged a legal claim. Lord Balfour suggested an alternative which was accepted and included in the preamble immediately after the paragraph quoted above:

Whereas recognition has thereby [i.e. by the Treaty of Sèvres] been given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine, and to the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country;[179]

In the body of the document, the Zionist Organization was mentioned in Article 4; in the September 1920 draft, a qualification was added which required that "its organisation and constitution" must be "in the opinion of the Mandatory appropriate".[90] A "Jewish agency" was mentioned three times: in Articles 4, 6 and 11.[90] Article 4 of the mandate provided for "the recognition of an appropriate Jewish agency as a public body for the purpose of advising and co-operating with the Administration of Palestine in such economic, social and other matters as may affect the establishment of the Jewish National Home and the interests of the Jewish population of Palestine," effectively establishing what became the "Jewish Agency for Palestine". Article 7 stated, "The Administration of Palestine shall be responsible for enacting a nationality law. There shall be included in this law provisions framed so as to facilitate the acquisition of Palestinian citizenship by Jews who take up their permanent residence in Palestine."[177] The proviso to this objective of the mandate was that "nothing should be done which might prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine".[177]

Religious and communal issues (Articles 13–16 and 23)

Religious and communal guarantees, such as freedom of religion and education, were made in general terms without reference to a specific religion.[90] The Vatican and the Italian and French governments concentrated their efforts on the issue of the Holy Places and the rights of the Christian communities,[180] making their legal claims on the basis of the former Protectorate of the Holy See and the French Protectorate of Jerusalem. The Catholic powers saw an opportunity to reverse the gains made by the Greek and Russian Orthodox communities in the region during the previous 150 years, as documented in the Status Quo.[181] The Zionists had limited interest in this area.[182]

Britain would assume responsibility for the Holy Places under Article 13 of the mandate. The idea of an International Commission to resolve claims on the Holy Places, formalised in Article 95 of the Treaty of Sèvres, was taken up again in article 14 of the Palestinian Mandate. Negotiations about the commission's formation and role were partly responsible for the delay in ratifying the mandate. Article 14 of the mandate required Britain to establish a commission to study, define, and determine the rights and claims relating to Palestine's religious communities. This provision, which called for the creation of a commission to review the Status Quo of the religious communities, was never implemented.[183][184]

Article 15 required the mandatory administration to ensure that complete freedom of conscience and the free exercise of all forms of worship were permitted. According to the article, "No discrimination of any kind shall be made between the inhabitants of Palestine on the ground of race, religion or language. No person shall be excluded from Palestine on the sole ground of his religious belief." The High Commissioner established the authority of the Orthodox Rabbinate over the members of the Jewish community and retained a modified version of the Ottoman Millet system. Formal recognition was extended to eleven religious communities, which did not include non-Orthodox Jews or the Protestant Christian denominations.[185]

Transjordan (Article 25 and Transjordan memorandum)

The public clarification and implementation of Article 25, more than a year after it was added to the mandate, misled some "into imagining that Transjordanian territory was covered by the conditions of the Mandate as to the Jewish National Home before August 1921".[i] This would, according to professor of modern Jewish history Bernard Wasserstein, result in "the myth of Palestine's 'first partition' [which became] part of the concept of 'Greater Israel' and of the ideology of Jabotinsky's Revisionist movement".[ii][iii] Palestinian-American academic Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, then chair of the Northwestern University political science department, suggested that the "Jordan as a Palestinian State" references made by Israeli spokespeople may reflect "the same [mis]understanding".[iv][188]

On 25 April 1923, five months before the mandate came into force, the independent administration was recognised in a statement made in Amman:

Subject to the approval of the League of Nations, His Britannic Majesty will recognise the existence of an independent Government in Trans-jordan under the rule of His Highness the Amir Abdullah, provided that such Government is constitutional and places His Britannic Majesty in a position to fulfil his international obligations in respect of the territory by means of an Agreement to be concluded with His Highness.[189][190]

Legality

The legality of the mandate has been disputed in detail by scholars, particularly its consistency with Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations.[191][192][193][194][195][t] According to the mandate's preamble, the mandate was granted to Britain "for the purpose of giving effect to the provisions of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations". That article, which concerns entrusting the "tutelage" of colonies formerly under German and Turkish sovereignty to "advanced nations", specifies "[c]ommunities formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire" which "have reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognised subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone."[197] During the mandate, Palestinian Arab leaders cited the article as proving their assertion that the British were obliged (under the terms of the mandate) to facilitate the eventual creation of an independent Arab state in Palestine.[198]

Borders

Before World War I, the territory which became Mandatory Palestine was the former Ottoman Empire divisions of the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem and the southern part of the Beirut Vilayet; what became Transjordan was the southern Vilayet of Syria and the northern Hejaz Vilayet.[199] During the war, the British military divided the Hejaz and Egyptian Expeditionary Force theatres of war along a line from a point south of Akaba to a point south of Ma'an. The EEF theatre was divided between its main theatre in Palestine and the Syrian theatre, including Transjordan, which was led by Faisal's Arab Revolt army.[200] The post-war military administrations OETA South and OETA East, the latter with an Arab governor, split the territory in the same way;[201][202] Professor Yitzhak Gil-Har notes that "the military administration [in Palestine] always treated Trans-Jordan as a separate administration outside its jurisdiction".[201] In 1955, Professor Uri Ra'anan wrote that the OETA border system "politically, if not legally, was bound to influence the post-war settlement".[203]

At a private 13 September 1919 meeting during the Paris Peace Conference, Lloyd George gave Georges Clemenceau a memorandum which said that British Palestine would be "defined in accordance with its ancient boundaries of Dan to Beersheba".[204][u]

The biblical concept of Eretz Israel and its re-establishment as a modern state was a basic tenet of the original Zionist program. Chaim Weizmann, leader of the Zionist delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, presented a Zionist statement on 3 February 1919 that declared the Zionists' proposed borders and resources "essential for the necessary economic foundation of the country" including "the control of its rivers and their headwaters".[206][better source needed] These borders included present day Israel and the Israeli-occupied territories, western Jordan, southwestern Syria and southern Lebanon "in the vicinity south of Sidon".[207][better source needed] Neither Palestinians nor any other Arabs were involved in the discussions which determined the boundaries of Mandatory Palestine.[xxxii][208]

Palestine-Egypt border

The first border which was agreed upon was with British-ruled Egypt.[210] This boundary traced back to 1906, when the Taba Crisis marked the culmination of longstanding disputes over the Sinai and Negev regions between the British and Ottomans. On 9 May 1919, a memorandum of the British political delegation to the Paris Peace Conference stated that the British intended to adopt the border between Egypt and the Ottoman Empire which was established in 1906.[211] The decision, a compromise between Zionist aspirations for the el-Arish–Rafah–Aqaba triangle[xxxiii] and various British proposals, which favored assigning most of the Negev to Egypt,[215][216] was already well-defined on maps.[211]

The Negev region was added to Palestine on 10 July 1922 after its concession by British representative John Philby "in Trans-Jordan's name"; although not usually considered part of the region of Palestine, the Zionist Organization had lobbied for Palestine to be given access to the Red Sea.[xxxiv] Abdullah's requests for the Negev to be added to Transjordan in late 1922 and 1925 were rejected.[218]

Northern borders

The determination of the mandate's northern border was a far longer and more complex process than for the other borders.[219] The two primary differences were that this border separated French– and British–controlled areas, and it ran through heavily populated areas which had not been separated. The other borders separated British Palestine from British Egypt and British Transjordan, and ran primarily through sparsely-inhabited areas.[220]

The northern boundary between the British and French mandates was broadly defined by the Franco-British Boundary Agreement of December 1920; this became known as the Paulet–Newcombe Agreement for French Lieutenant Colonel N. Paulet and British Lieutenant Colonel S. F. Newcombe, who were appointed to lead the 1923 Boundary Commission to finalise the agreement.[221] It placed most of the Golan Heights in the French sphere, and established a joint commission to settle and mark the border. The commission submitted its final report on 3 February 1922; it was approved with some caveats by the British and French governments on 7 March 1923, several months before Britain and France assumed their mandatory responsibilities on 29 September 1923.[222][223] Under the treaty, Syrian and Lebanese residents would have the same fishing and navigation rights on Lake Hula, the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan River as citizens of Mandatory Palestine, but the government of Palestine would be responsible for policing the lakes. The Zionist movement pressured the French and British to include as many water sources as possible in Palestine during the demarcating negotiations. The movement's demands influenced the negotiators, leading to the inclusion of the Sea of Galilee, both sides of the Jordan River, Lake Hula, the Dan spring, and part of the Yarmouk River. As High Commissioner of Palestine, Herbert Samuel had demanded full control of the Sea of Galilee.[224] The new border followed a 10-metre-wide (33 ft) strip along the northeastern shore.[225] After the settlement of the northern-border issue, the British and French governments signed an agreement of good neighbourly relations between the mandated territories of Palestine, Syria and Lebanon on 2 February 1926.[226]

Palestine-Transjordan border

Transjordan had been part of the Syria Vilayet – primarily the sanjaks of Hauran and Ma'an (Kerak) – under the Ottomans. Since the end of the war it was part of captured territory placed under the Arab administration of OETA East,[228][202] which was subsequently declared part of Faisal's Arab Kingdom of Syria. The British were content with that arrangement because Faisal was a British ally; the region fell within the indirect sphere of British influence according to the Sykes–Picot Agreement, and they did not have enough troops to garrison it.[66][xxxv]

Throughout the drafting of the mandate, the Zionist Organization advocated for territory east of the river to be included in Palestine. At the peace conference on 3 February 1919, the organization proposed an eastern boundary of "a line close to and West of the Hedjaz Railway terminating in the Gulf of Akaba";[101] the railway ran parallel to, and 35–40 miles (about 60 km) east of, the Jordan River.[230] In May, British officials presented a proposal to the peace conference which included maps showing Palestine's eastern boundary just 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) east of the Jordan.[xxxvi] No agreement was reached in Paris; the topic was not discussed at the April 1920 San Remo conference, at which the boundaries of the "Palestine" and "Syria" mandates were left unspecified to "be determined by the Principal Allied Powers" at a later stage.[34][48]

The Jordan River was finally chosen as the border between the two territories;[xxxvii] this was documented in Article 25 of the mandate, approved by Curzon on 31 March 1921,[87] which set the boundary as simply "the Jordan [river]". No further definition was discussed until mid-1922,[187] when the boundary became significant due to negotiations on the Rutenberg hydroelectric power-plant and the Constitution of Mandatory Palestine (which did not apply to Transjordan, highlighting the need for a clear definition).[232] The latter's publication on 1 September was the first official statement of the detailed boundary,[233] which was repeated in a 16 September 1922 Transjordan memorandum: "from a point two miles west of the town of Akaba on the Gulf of that name up the centre of the Wady Araba, Dead Sea and River Jordan to its junction with the River Yarmuk; thence up the centre of that river to the Syrian Frontier".[234]

Transjordan-Arabia border

The southern border between Transjordan and Arabia was considered strategic for Transjordan to avoid being landlocked, with intended access to the sea via the Port of Aqaba. The southern region of Ma'an-Aqaba, a large area with a population of only 10,000,[235] was administered by OETA East (later the Arab Kingdom of Syria, and then Mandatory Transjordan) and claimed by the Kingdom of Hejaz.[236][237] In OETA East, Faisal had appointed a kaymakam (sub-governor) at Ma'an; the kaymakam at Aqaba, who "disregarded both Husein in Mecca and Feisal in Damascus with impunity",[238] had been instructed by Hussein to extend his authority to Ma'an.[236] This technical dispute did not become an open struggle, and the Kingdom of Hejaz was to take de facto control after Faisal's administration was defeated by the French.[xxxviii] After the 1924–25 Saudi conquest of Hejaz, Hussein's army fled to the Ma'an region (which was then formally announced as annexed by Abdullah's Transjordan). Ibn Saud privately agreed to respect this position in an exchange of letters at the time of the 1927 Treaty of Jeddah.[239]

Transjordan-Iraq border

The location of the Eastern border between Transjordan and Iraq was considered strategic with respect to the proposed construction of what became the Kirkuk–Haifa oil pipeline.[239] It was first set out on 2 December 1922, in a treaty to which Transjordan was not party to – the Uqair Protocol between Iraq and Nejd.[240] It described the western end of the Iraq-Nejd boundary as "the Jebel Anazan situated in the neighbourhood of the intersection of latitude 32 degrees north longitude 39 degrees east where the Iraq-Najd boundary terminated", thereby implicitly confirming this as the point at which the Iraq-Nejd boundary became the Transjordan-Nejd boundary.[240] This followed a proposal from T.E.Lawrence in January 1922 that Transjordan be extended to include Wadi Sirhan as far south as al-Jauf, in order to protect Britain's route to India and contain Ibn Saud.[241]

Impact and termination

Mandatory Palestine

The British controlled Palestine for almost three decades, overseeing a succession of protests, riots and revolts by the Jewish and Palestinian Arab communities.[242] The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was passed on 29 November 1947; this envisaged the creation of separate Jewish and Arab states operating under economic union, and with Jerusalem transferred to UN trusteeship.[243] Two weeks later, Colonial Secretary Arthur Creech Jones announced that the British Mandate would terminate on 15 May 1948.[244][v] On the last day of the mandate, the creation of the State of Israel was proclaimed and the 1948 Arab–Israeli War began.[244]

Emirate of Transjordan

In April 1923, five months before the mandate came into force, Britain announced their intention to recognise an "independent Government" in Transjordan.[246][188] Transjordan became largely autonomous under British tutelage in accordance with a 20 February 1928 agreement, and became fully independent under a treaty with Britain on 22 March 1946.[246]

Key dates from Balfour Declaration to mandate becoming effective

| Administration | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Date | Document | Palestine | Transjordan | |

| Pre-war | Ottoman sanjaks: Jerusalem, Nablus and Acre[247] | Ottoman sanjaks: Hauran and Ma'an[248] | |||

| 1915 | 24 October | McMahon–Hussein Correspondence[249] | |||

| 1916 | 3 January | Sykes–Picot Agreement[249] | |||

| 1917 | 2 November | Balfour Declaration[249] | |||

| 1918 | 23 October | OETA South declared under British administration[201] | OETA East declared under Arab-British administration[201] | ||

| 1 December | France cede claim over Palestine[250] | ||||

| 1919 | 28 June | Covenant of the League of Nations signed, establishing mandate system | |||

| 1920 | 10 January | Covenant of League of Nations comes into effect | |||

| 8 March | Kingdom of Syria declared[251] | ||||

| 25 April | Mandate assigned at San Remo[34] | ||||

| 1 July | Civil administration begins as High Commissioner appointed[252] | ||||

| 23 July | Becomes a no-man's land after Battle of Maysalun[59] | ||||

| 10 August | Treaty of Sèvres signed (never ratified)[253] | ||||

| 11–26 August | Curzon policy: "no question of setting up any British administration in the area"[56] | ||||

| 21 November | Abdullah's army moves into southern Transjordan[79][81] | ||||

| 7 December | First draft submitted to the League of Nations[254] | ||||

| 23 December | Agreement on northern boundary[255] | ||||

| 1921 | 12–30 March | Cairo conference. Article 25 (Transjordan) drafted[251] | Proposal to add the area to Palestine mandate, as separate Arab entity[251] | ||

| 11 April | Emirate of Transjordan established[80] | ||||

| 1922 | 24 July | Mandate terms approved[26] | |||

| 10 August | Palestine constitution signed[256] | ||||

| 16 September | Transjordan memorandum accepted[251] | ||||

| 23 October | 1922 census of Palestine[257] | ||||

| 1923 | 25 April | Independence announcement[189] | |||

| 29 September | Mandate comes into effect[258] | ||||

See also

Notes

Primary supporting quotes

- ^ Ali Allawi explained this as follows: "When Faisal left the meeting with Weizmann to explain his actions to his advisers who were in a nearby suite of offices at the Carlton Hotel, he was met with expressions of shock and disbelief. How could he sign a document that was written by a foreigner in favour of another foreigner in English in a language of which he knew nothing? Faisal replied to his advisers as recorded in ‘Awni ‘Abd al-Hadi's memoirs, "You are right to be surprised that I signed such an agreement written in English. But I warrant you that your surprise will disappear when I tell you that I did not sign the agreement before I stipulated in writing that my agreement to sign it was conditional on the acceptance by the British government of a previous note that I had presented to the Foreign Office… [This note] contained the demand for the independence of the Arab lands in Asia, starting from a line that begins in the north at Alexandretta-Diyarbakir and reaching the Indian Ocean in the south. And Palestine, as you know, is within these boundaries… I confirmed in this agreement before signing that I am not responsible for the implementation of anything in the agreement if any modification to my note is allowed""[42]

- ^ -The Times reported Weizmann's statement on 8 May 1920 as follows: "There are still important details outstanding, such as the actual terms of the mandate and the question of the boundaries in Palestine. There is the delimitation of the boundary between French Syria and Palestine, which will constitute the northern frontier and the eastern line of demarcation, adjoining Arab Syria. The latter is not likely to be fixed until the Emir Faisal attends the Peace Conference, probably in Paris."[46]

- ^ a b In a telegram sent to the British Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Lord Hardinge on 26 April 1920, before leaving San Remo, Curzon wrote: "[t]he boundaries of these States will not be included in the Peace Treaty [with Turkey] but are also to be determined by the principal Allied Powers. As regards Palestine an Article is also to be inserted in [the] Peace Treaty entrusting administration to a mandatory, whose duties are defined by a verbatim repetition of Mr.Balfour’s declaration of November 1917. Here again the boundaries will not be defined in [the] Peace Treaty but are to be determined at a later date by principal Allied Powers. The mandatory is not mentioned in [the] Treaty, but by an independent decision of Supreme Council was declared to be Great Britain."[47][48]

- ^ A year after stepping down as Attorney general of Palestine, Norman Bentwich described the historical situation as follows: "The High Commissioner had ... only been in office a few days when Emir Faisal ... had to flee his kingdom" and "The departure of Faisal and the breaking up of the Emirate of Syria left the territory on the east side of Jordan in a puzzling state of detachment. It was for a time no-man's-land. In the Ottoman regime the territory was attached to the Vilayet of Damascus; under the Military Administration it had been treated a part of the eastern occupied territory which was governed from Damascus; but it was now impossible that that subordination should continue, and its natural attachment was with Palestine. The territory was, indeed, included in the Mandated territory of Palestine, but difficult issues were involved as to application there of the clauses of the Mandate concerning the jewish National Home. The undertakings given to the Arabs as to the autonomous Arab region included the territory. Lastly, His Majesty's Government were unwilling to embark on any definite commitment, and vetoed any entry into the territory by the troops. The Arabs were therefore left to work out their destiny."[59]

- ^ The day before the meeting, on 20 August, Samuel noted in his diary: "It is an entirely irregular proceeding, my going outside my own jurisdiction into a country which was Faisal's, and is still being administered by the Damascus Government, now under French influence. But it is equally irregular for a government under French influence to be exercising functions in territory which is agreed to be within the British sphere: and of the two irregularities I prefer mine."[72]

- ^ Curzon's 26 August 1920 telegram stated that: "His Majesty's Government have no desire to extend their responsibilities in Arab districts and must insist on strict adherence to the very limited assistance which we can offer to a native administration in Trans-jordania as stated in my telegram No. 80 of August 11th. There must be no question of setting up any British administration in that area and all that may be done at present is to send a maximum of four or five political officers with instructions on the lines laid down in my above mentioned telegram."[57][58][74]

- ^ Curzon wrote, "His Majesty's Government are already treating 'Trans-Jordania' as separate from the Damascus State, while at the same time avoiding any definite connection between it and Palestine, thus leaving the way open for the establishment there, should it become advisable, of some form of independent Arab government, perhaps by arrangement with King Hussein or other Arab chiefs concerned."[75][76][77]

- ^ The occasion of the Cairo Conference offered an opportunity to clarify the matter. As Lloyd George and Churchill both agreed, the solution consisted of treating Transjordan as "an Arab province or adjunct of Palestine" while at the same time "preserving [the] Arab character of the area and administration."... Despite the objection from Eric Forbes Adam in the Middle East Department that it was better not to raise the question of different treatment publicly by suggesting new amendments or additions to the mandates, the legal officers of the Colonial and Foreign offices, meeting on 21 March 1921, deemed it advisable, as a matter of prudence, to insert in advance general clauses giving the mandatory "certain discretionary powers" in applying the Palestine and Mesopotamia mandates to Transjordan and Kurdistan respectively"[87]

- ^ In July, Balfour had authorised Eric Forbes Adam of the Foreign Office, who at that time served with the Peace Delegation in Paris, to discuss with Weizmann, Frankfurter and Ganz the draft for the Palestine Mandate "on the supposition that Great Britain were to obtain the mandate for Palestine".[89]

- ^ Weizmann wrote in his memoirs, "Curzon had by now taken over from Balfour at the Foreign Office, and was in charge of the actual drafting of the Mandate. On our side we had the valuable assistance of Ben V. Cohen, who stayed on with us in London after most of his fellow-Brandeisists had resigned from the Executive and withdrawn from the work. Ben Cohen was one of the ablest draftsmen in America, and he and Curzon's secretary — young Eric Forbes-Adam, highly intelligent, efficient and most sympathetic — fought the battle of the Mandate for many months."[96]

- ^ The British Foreign Office confirmed the position in 1946, in discussions over the independence of Transjordan, stating that "the clauses of the Palestine Mandate relating to the establishment of a Jewish national home were, with the approval of the League of Nations, never applied in Transjordan. His Majesty's Government have therefore never considered themselves under any obligation to apply them there"[105]

- ^ Weizmann wrote in his memoirs, "As the drafting of the Mandate progressed, and the prospect of its ratification drew nearer, we found ourselves on the defensive against attacks from every conceivable quarter — on our position in Palestine, on our work there, on our good faith. The spearhead of these attacks was an Arab delegation from Palestine, which arrived in London via Cairo, Rome and Paris in the summer of 1921, and established itself in London at the Hotel Cecil."[116]

- ^ Turkey’s lead negotiator, İsmet İnönü, explained during the negotiations on 23 January 1923 that he "did not ... feel bound to recognise the existence or the legality of any mandate over these territories"[122] and had "never accepted the principle or recognised the fact of any mandate".[123]

- ^ Diplomat and Sykes's biographer, Shane Leslie, wrote in 1923 about Sykes: "His last journey to Palestine had raised many doubts, which were not set at rest by a visit to Rome. To Cardinal Gasquet he admitted the change of his views on Zionism, and that he was determined to qualify, guide and, if possible, save the dangerous situation which was rapidly arising. If death had not been upon him it would not have been too late."[135]

- ^ Churchill concluded the Commons debate with the following argument: "Palestine is all the more important to us ... in view of the ever-growing significance of the Suez Canal; and I do not think £1,000,000 a year ... would be too much for Great Britain to pay for the control and guardianship of this great historic land, and for keeping the word that she has given before all the nations of the world."[140]

- ^ Nineteenth Session of the Council, Twelfth Meeting, St James' Palace, London on 22 July 1922, at 3:30p.m: "The Council decided that the mandate for Palestine was approved with the revised text of Article 14, and that the mandate for Syria would come automatically into force as soon as the negotiations between the French and Italian Governments had resulted in a final agreement. It was further understood that the two mandates should, come into force simultaneously."[159]

- ^ Nineteenth Session of the Council, Thirteenth Meeting, St James' Palace, London on 24 July 1922, at 3 p.m.: "In view of the declarations which have just been made, and of the agreement reached by all the Members of the Council, the articles of the mandates for Palestine and Syria are approved. The mandates will enter into force automatically and at the same time, as soon as the Governments of France and Italy have notified the President of the Council of the League of Nations that they have reached an agreement on certain particular points in regard to the latter of these mandates."[160]

- ^ At a private meeting of the Council of the LoN on 29 September 1923, the minutes read: "M. SALANDRA stated, on behalf of his Government, that a complete agreement had been reached between the Governments of France and Italy on the subject of the mandate for Syria. There was therefore nothing to prevent the immediate entry into force of the mandate for Palestine. M. HANOTAUX, on behalf of his Government, confirmed M. Salandra's statement and pointed out that in view of this agreement the Council's resolution of July 24th, 1922, would come into operation and the mandates for Palestine and Syria would enter into force automatically and at the same time. Sir Rennell RODD expressed his satisfaction that, this question had been finally settled. The COUNCIL noted that, in view of the agreement between the Governments of France and Italy in respect of the mandate for Syria, the mandates for Palestine and Syria would now enter into force automatically and at the same time."[167]

- ^ Weizmann wrote in his memoirs, "The most serious difficulty arose in connection with a paragraph in the Preamble — the phrase which now reads: 'Recognizing the historical connection of the Jews with Palestine.' Zionists wanted to have it read: 'Recognizing the historic rights of the Jews to Palestine.' But Curzon would have none of it, remarking dryly: 'If you word it like that, I can see Weizmann coming to me every other day and saying he has a right to do this, that or the other in Palestine! I won't have it!' As a compromise, Balfour suggested 'historical connection,' and 'historical connection' it was. I confess that for me this was the most important part of the Mandate. I felt instinctively that the other provisions of the Mandate might remain a dead letter, e.g, ' to place the country under such political, economic and administrative conditions as may facilitate the development of the Jewish National Home.' All one can say about that point, after more than twenty-five years, is that at least Palestine has not so far been placed under a legislative council with an Arab majority — but that is rather a negative brand of fulfilment of a positive injunction."[116][94]