Ometepe

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Lake Nicaragua (Lake Cocibolca) |

| Coordinates | 11°30′N 85°35′W / 11.500°N 85.583°W |

| Total islands | 1 |

| Major islands | 1 |

| Area | 276 km2 (107 sq mi) |

| Length | 31 km (19.3 mi) |

| Width | 10 km (6 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,610 m (5280 ft) |

| Highest point | Concepción |

| Administration | |

| Department | Rivas |

| Largest settlement | Altagracia (pop. 4,081) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 29,684 (June 2005) |

| Pop. density | 107.6/km2 (278.7/sq mi) |

Ometepe is an island formed by two volcanoes rising out of Lake Nicaragua, located in the Rivas Department of the Republic of Nicaragua. Its name derives from the Nahuatl words ome (two) and tepetl (mountain), meaning "two mountains".[1] It is the largest island in Lake Nicaragua.

The two volcanoes (Concepción and Maderas) are joined by a low isthmus to form one island. Ometepe has an area of 276 square kilometres (107 sq mi). It is 31 kilometres (19 mi) long and 5 to 10 kilometres (3.1 to 6.2 mi) wide.[2] The island has an economy based on livestock, agriculture, and tourism. Plantains are the major crop.

Inhabitants

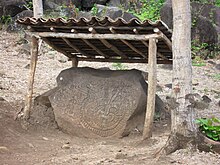

The island first became inhabited during the Dinarte phase (c. 2000 BC – 500 BC), although evidence is questionable. The first known inhabitants were speakers of Macro-Chibchan languages. Traces of this past can still be found in petroglyphs and stone idols on the northern slopes of the Maderas volcano. The oldest date from 300 BC. Several centuries later, Chorotega and Nicarao people continued to add to the petroglyphs and created statues on Ometepe carved from basalt rock.

After the Spaniards conquered the Central American region in the 16th century, pirates began prowling Lake Nicaragua. They came in from the Caribbean Sea via the San Juan River. The inhabitants of Ometepe were hard hit. The pirates kidnapped women, stole the inhabitants' animals, possessions, and harvest, and erected settlements on the shore, making it their refuge. This made the local population move to higher grounds on the volcanoes in search of shelter. The island was finally settled by the Spanish conquistadors at the end of the 16th century.

The most important villages on the island are Altagracia (pop. 4081), on the northeastern side, and Moyogalpa (pop. 2905), with its harbor on the northwestern side of the island. These two villages are the centers of the two municipalities and the island is divided between the two. Many traditions have been kept alive, thus inhabitants of Ometepe celebrate more religious and folk festivals than anywhere else in Nicaragua.

Today, Ometepe is developing tourism and ecotourism, with the archaeological past and the bounty of its nature sanctuary, the exotic vegetation, animal and bird life as drawcards. Ometepe Airport opened in 2014.[3][4]

Volcanoes

Concepción is on the northwest half of the island. It has a base of 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) beneath its symmetrical cone, and it is an active volcano.[5][6][7] Because of its symmetry, it has been considered extremely beautiful. The volcano is believed to have risen in the early Holocene epoch and, through continual eruptions, now reaches an altitude of 1,610 metres (5,280 ft) making Ometepe the world's highest lake island.[citation needed]

After a long period of dormancy, an eruption began at Concepción on December 8, 1880. This eruption was extensive, and the volcano remained active for a year. More eruptions followed in 1883, 1889, 1902, 1907, and 1924. In 2005, an earthquake measuring 6.2 on the Richter scale occurred as a result of increasing pressure within the volcano. Cracks appeared on roads throughout the island and an advisory to leave the island was issued. This was the first minor eruption since 1999. The most recent eruption was in 2010 and although it was extremely violent, few of the inhabitants heeded the order from the government in Managua to evacuate the island and little damage was done.[citation needed]

The southeast half of the island consists of Maderas, which has a crater lake and supports a diverse rainforest environment. Maderas is also believed to have risen in the Holocene epoch and rises 1,394 metres (4,573 ft) above sea level. It is considered extinct or possibly dormant. The large lagoon in its crater was discovered on April 15, 1930, by farmer Casimiro Murillo. The sides of the volcano are mainly covered with coffee and tobacco plantations while the remainder is rain forest. Much of this part of the island is now a nature reserve.[8]

The volcanic ash has made the soil of this island extremely fertile, allowing continuous planting. The volcanoes are visible from everywhere on the island, and life on Ometepe revolves closely around them. They also play an important part in the myths and legends of the island, which once served as an indigenous burial ground.

IUGS geological heritage site

In respect of it being 'a type example of volcano spreading and volcano-tectonic interactions in the volcanic arc sedimentary basin of Lake Nicaragua', the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) included 'La Isla de Ometepe: Quaternary volcanoes in the Lake Nicaragua sedimentary basin' in its assemblage of 100 'geological heritage sites' around the world in a listing published in October 2022. The organisation defines an IUGS Geological Heritage Site as 'a key place with geological elements and/or processes of international scientific relevance, used as a reference, and/or with a substantial contribution to the development of geological sciences through history.'[9]

Archaeology

Ometepe Island is generally included within the archaeological area of "Greater Nicoya", which also encompasses the Rivas area on the lake shore and descends into Costa Rican Nicoya Peninsula. Due to deposits of volcanic ash over millennia, the soil is very fertile, allowing constant planting without fallowing. This rich environment has allowed the island to be continuously inhabited since the Dinarte phase (c. 2000 BC – 500 BC). There is a time period classified as the “Ometepe period” (AD 1350 – 1550) or "Greater Nicoyan Period", which corresponds to the Mesoamerican Postclassic period. This period is associated with the migration of the Nicarao (Nahua speakers) into the area of Greater Nicoya.[10]

The archaeologists who have done fieldwork on the island over the years are:

- 1880s: J.F. Bransford;

- 1959-1961: excavations by Dr. Gordon Willey and Albert Norweb;

- 1962: Wolfgang Haberland and Peter Schmidt;

- 1995–1999: Suzanne M. Baker - Ometepe Petroglyph Project.[11]

Ceramics

Dr. Gordon Willey and Albert Norweb excavated the Cruz site (named after the Cruz Hacienda), on the North East part of the island. This site is important because it produced nearly 30,000 sherds, most of which belonged to the Late Polychrome Period. The upper levels of the site produced the diagnostic ceramic types which came to define the Late Polychrome Period for the whole of the Rivas area. Pieces were also found from the San Jorge phase of the Zoned Bichrome Period.[12]

The Ceramic Type "Ometepe Red Slipped-Incised" is found on Ometepe Island. It is a Late Polychrome Period ceramic type, and it is usually found in the form of jar sherds. This type of ceramic is identifiable because it is scraped on both the inside and out, and smoothing and polishing is done on the exterior body and rim. The slip, over the rim and outside, is a dull red to brown, while only the inside of the neck is slipped. Lines are cut into the lip of the jar, and triangles are the most common motif, either interlocking or meeting tip to tip. Other ceramic types found on the island include: Granada Polychrome from the Middle Polychrome Period, Castillo Late Polychrome, and Luna Ware Polychrome.[12]

Petroglyphs

The Ometepe Petroglyph Project was a volunteer field survey of the Maderas half of Ometepe from 1995 to 1999. This project intensively surveyed 15 km of the Maderas half of the island over five field seasons. The project mapped 73 archaeological sites within this 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) area, including almost 1700 petroglyph panels on 1400 boulders.

Of the 73 sites surveyed by the Ometepe Petroglyph Project, petroglyphs were recorded at all but one. Many of the petroglyphs on Ometepe contain spirals, and “meander” across the rock face. Stylized turtles are a common motif for the area.

The petroglyphs of Ometepe include some forms which are less common. Figures in many of the depictions are described as having “bowling ball faces” on human figures. As noted above, spirals are common, and are apparently used in several ways. Two attached spirals appear to represent the island, with its two volcanoes. Spirals also are used to depict the head of anthropomorphic figures. Some figures resemble Mesoamerican depictions of Nagual, suggesting the shared practice of Tonal spirituality.[13]

Some of the unusual formations seen within the petroglyphs on Ometepe include seats or steps carved into boulders, ovals, and big grooves. The purpose behind these forms has not yet been explained.

Between the 1995 and 1996 field seasons, ten sites were recorded. The greatest concentration of petroglyphs was noted at N-RIO-3, probably recorded by Haberland as Om-38. Located along the slopes and at the top and of a ridge, the site contains 82 boulders with petroglyphs, six mortars, two metates and a scatter of ceramics and chert lithics. Of the 149 petroglyphs recorded during 1996, most were located on land owned by the cooperative at the hacienda. When the program was expanded in 1997, to include volunteers, 20 volunteers participated in recording fifteen additional sites. The most impressive site, N-RIO-19, was greater than 180,000 square meters in area. Ninety-two petroglyphs, over 30 house mounds, stone statuary fragments, and pottery from at least three different periods of occupation were recorded at the site, and the material was being studied in Managua.

The Ometepe Petroglyph project is an interesting example of modern technology assisting in the recording of archaeological sites. As the prehistoric art sites were being surveyed and recorded, pictures were taken of each site in both color and black and white. A video was even made at one site. Photos were then uploaded into a computer, and the Photoshop program was then used to increase the contrast of the photos, increasing the visibility of the petroglyphs pictured. This allowed for a more accurate record of sites that by necessity were photographed in less than ideal conditions and lighting. In addition to the remote area and poor lighting, on Ometepe Island, the depth of the engraved lines on petroglyphs thus far recorded varies from “immeasurably shallow” to around three centimeters (Ometepe Petroglyph Project Website, 2006).

Wildlife

Ometepe harbors large populations of the white-faced capuchin monkey, also called white-headed capuchin, (Cebus capucinus) and populations of the mantled howler monkey (Alouatta palliata). Efforts are being made to study and protect these animals. The Ometepe Biological Field School is situated on the Maderas side of the island. Here, students and scientists from all over the world come to study the unique flora and fauna of the area. The lake surrounding Ometepe harbors many species of aquatic animals, notably the Nicaragua shark which until recently was thought to be a unique species of freshwater shark but has since been shown to be continuous with ocean populations.[14] Small populations of spider monkeys (Ateles s.) inhabit very small islands within Lake Nicaragua. These populations exist solely due to humans and many of the local fishermen routinely stop by to feed these troops. The local form of the rice rat Oryzomys couesi is distinctive and may represent a separate subspecies.[15]

Transportation

Ometepe La Paloma Airport (OMT) serves the island with service from La Costeña.[16] The airlines offers flights to Managua, San Carlos, and San Juan de Nicaragua (Greytown). Flights to Managua operated twice a week, every Thursday and Sunday.[16][17] The flights were discontinued due to low demand.[18] There are three ferry ports on the island and there are regular ferries and lanchas[19] to and from San Carlos and Granada twice a week (seasonally and at night[20]) as well as several times a day to and from San Jorge, Rivas. The roads on the island have recently been paved with concrete pavers for all the major roads on the island. the secondary roads outside the cities are all dirt or gravel and often heavily washed out and not passable without 4WD or a motorcycle.[21]

Tourism

In 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the island of Ometepe had 141,178 tourist arrivals.[22] The majority arrive between mid-November and mid-May.[22] The majority of the visitors arrive via ferry from San Jorge to Moyogalpa.[20]

Gallery

- A river on Ometepe

- Concepción as seen from Finca Magdalena, Ometepe, Nicaragua

- Ometepe from space, January 1997

- Volcanic rocks on Ometepe

See also

Notes

- ^ Cerna, Celeste (August 4, 2016). "Unite a la aventura y explorá la Isla de Ometepe" [Join the adventure and explore the Island of Ometepe]. El Nuevo Diario (in Spanish). Archived from the original on December 15, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ "Tourism: Island of Ometepe". EAAI. Archived from the original on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ Ometepe Island Inaugurates Airport with First Flight Archived June 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ La Paloma Airport[permanent dead link]

- ^ Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. p. 280. ISBN 0-89577-087-3.

- ^ "Ometepe Island Info - Volcán Concepción". ometepeislandinfo.com. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- ^ Baker, Suzanne. "Petroglyph Types found on Ometepe Island, Nicaragua". Culturelink Fieldwork Project. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ "Volcán Maderas". Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ "The First 100 IUGS Geological Heritage Sites" (PDF). IUGS International Commission on Geoheritage. IUGS. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ McCafferty & Steinbrenner 2005.

- ^ Baker, Suzanne M. (2010). The Rock Art of Ometepe Island Nicaragua: Motif Classification Quantification and Regional Comparisons. Oxford, England: Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-4073-0560-8.

- ^ a b Healy 1980.

- ^ Manion, Jessica (2016). "Remembering the Ancestors: Mortuary Practices and Social Memory in Pacific Nicaragua" (PDF). University of Calgary. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ Shark gallery Archived July 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jones, J.K., Jr. and Engstrom, M.D. 1986. Synopsis of the rice rats (genus Oryzomys) of Nicaragua. Occasional Papers, The Museum, Texas Tech University 103:1–23.

- ^ a b "Ometepe Island Info - Flying Into Our New Airport!". ometepeislandinfo.com. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- ^ Tim Rogers (14 May 2014). "Ometepe Island opens overdue airport". Nicaragua Dispatch.

- ^ "Flights from to Ometepe Island in Nicaragua". ometepenicaragua.com. Retrieved 2023-07-29.

- ^ "Ferry Ports". ometepeislandinfo.com. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Ferry Schedule". ometepeislandinfo.com. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ "Ometepe Island Info - Getting Around On The Island". ometepeislandinfo.com. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- ^ a b "Estadísticas de Turismo" (in Spanish). Instituto Nicaragüense de Turismo. pp. 1–90. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

References

- Healy, Paul F. (1980). Archaeology of the Rivas Region, Nicaragua. Ontario: Wilfrid Lauer University Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-094-4.

- Martin, James. "Ometepe Archaeological Project". Culturelink Fieldwork Project. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- McCafferty, Geoffrey G.; Steinbrenner, Larry (2005). "Chronological implications for Greater Nicoya from the Santa Isabel Project, Nicaragua" (PDF). Ancient Mesoamerica. 16 (1): 131–146. doi:10.1017/S0956536105050066. S2CID 162669977. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-19.

External links

- Ometepe at the Nicaraguan Institute of Tourism (in Spanish)

- Ometepe Island Tourist Information Site

- Travel Guide to the Ometepe Island

- Bainbridge Ometepe Sister Islands Association

- The Nicaraguan Lakes and Pacific Coast Habitat - Archaeology

- Best Backpacking Destination: Ometepe

- Ometepe Island

- Welcome to Ometepe

- Tourist Guide (Bilingual English/Spanish)