Occupy (book)

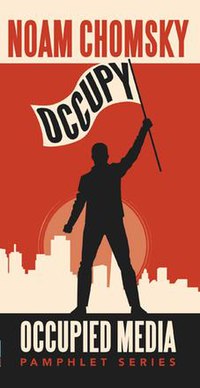

The cover of the first edition, published by the Zuccotti Park Press | |

| Author | Noam Chomsky |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Zuccotti Park Press (U.S.) Penguin Books (U.K.) |

Publication date | 2012 |

| Media type | Print (Paperback) |

| Pages | 122 |

| ISBN | 978-0-241-96401-9 |

Occupy is a short study of the Occupy movement written by the American academic and political activist Noam Chomsky. Initially published in the United States by the Zuccotti Park Press as the first title in their Occupied Media Pamphlet Series in 2012, it was subsequently republished in the United Kingdom by Penguin Books later that year.

An academic linguist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Chomsky first achieved fame for his work as a political activist during the 1960s and 1970s. A libertarian socialist, Chomsky is a prominent critic of capitalism, the role of western media and the foreign policy of the U.S. government, dealing with such issues in bestsellers like Manufacturing Consent (1988), Hegemony or Survival (2003) and Failed States (2006). With the birth of the Occupy Movement – devoted to socio-political change – in 2011, Chomsky became a vocal supporter for the protesters, writing articles and giving speeches on their behalf, several of which were collected together and published as Occupy.

The book opens with an introductory editor's note by Greg Ruggiero, praising the Occupy movement and its potential for the greater democratization of society. This is followed by the text to Chomsky's Howard Zinn Memorial Lecture, which he gave at Occupy Boston in Massachusetts. The third part of the book comprises Chomsky's interview with the New York University student Edward Radzivilovskiy, while the fourth contains the text of the InterOccupy conference call with Chomsky by Mikal Kamil and Ian Escuela. Part five offers an interview with Chomsky undertaken at the University of Maryland, while the book is rounded off by Chomsky's tribute to the late activist Howard Zinn and the National Lawyers Guild's legal advice to Occupy protesters.

Throughout the book, Chomsky discusses what the Occupy movement is and what it is demanding, as well as advocating ways in which it could gain greater support and achieve governmental reforms, using historical examples as evidence. Press reviews were largely positive, with some noting that Chomsky had taken a more moderate, reformist position than they expected of him.

Background

Noam Chomsky (1928–) was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Becoming academically involved in the field of linguistics, Chomsky eventually secured a job as Professor of Department of Linguistics & Philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In the field of linguistics, he is credited as the creator or co-creator of the Chomsky hierarchy, the universal grammar theory, and the Chomsky–Schützenberger theorem. Politically, Chomsky had held radical leftist views since childhood, identifying himself with anarcho-syndicalism and libertarian socialism. He is particularly known for his critiques of U.S. foreign policy and contemporary capitalism, and he has been described as a prominent cultural figure.[1]

First emerging in New York City in 2011, the Occupy movement was an international protest movement against social and economic inequality, its primary goal being to make the economic structure and power relations in society more favorable to the underclasses. Different local groups have different foci, but among the prime concerns is the claim that large corporations and the global financial system control the world in a way that disproportionately benefits a minority, undermines democracy and is unstable. It was widely seen as a reaction to the 2008–2012 global recession, an economic crisis that had led to high unemployment across the western world, and was also inspired by the Arab Spring, in which popular protest movements overthrew the governments of several countries in the Arab world. Chomsky became a supporter for the Occupy movement, joining protesters at some of their camps and advocating their cause in the mainstream press.

The book's original publisher, Zuccotti Park Press, was founded by Adelente Alliance, a Brooklyn-based non profit cultural and advocacy organization devoted to the Spanish-speaking community. Occupy was the first of a series of publications known as the Occupied Media Pamphlet Series. According to the Press, its purpose was to "produce accessible, affordable, pamphlet-size works by well-known and emerging voices who are inspired by a vision for a new society."[2] Chomsky dedicated his book to "the 6,705 people who have been arrested supporting Occupy" between September 24, 2011 to March 6, 2012.[3]

Synopsis

The book includes an editor's note, a brief section providing legal advice for American Occupy activists, and five sections written by Chomsky himself. Occupy opens with an editor's note written by Greg Ruggiero, in which he explains the basics to Chomsky's views on the Occupy movement, drawing quotes from his various public speeches in order to do so. Ruggiero also discusses Occupy's success in the United States, stating that it has helped to change media discussions by introducing terms like "the 99%" into popular discourse and also by bringing national attention to the plight of the impoverished. He remarks that the protest movement has not only helped to highlight the "heartlessness and inhumanity" of the socio-political system, but that it has also helped to provide solidarity with those "being crushed" under that system. Suggesting reasons for the movement's success, he optimistically describes the manner in which "People are waking up and coming out."[4]

The introduction is followed by a transcript of Chomsky's Howard Zinn Memorial Lecture, originally given to Occupy Boston in Dewey Square on October 22, 2011. Contrasting the hope of the working classes in the Great Depression of the 1930s with the pessimism of their contemporaries in the current recession, Chomsky discusses the changes to the U.S. economy that have occurred since the 1970s: de-industrialization, de-development and the rise of the financial sector at the expense of other parts of the economy. He notes how both Adam Smith and David Ricardo partly foresaw this situation. Highlighting the work of Tom Ferguson, he discusses how the political parties have come under the increasing control of the corporate sector. Proceeding to look at corruption among the 1%, he makes reference to both Citigroup and Alan Greenspan, before discussing the role that worker sit-ins and industry takeovers could play in democratizing the U.S. economy, as well as the threat posed by both nuclear war and environmental catastrophe, both problems exacerbated by the current capitalist system. Finally, he responds to questions posed by the audience, discussing the concept of corporate personhood, rejecting the idea that the U.S. elite could resort to fascism, and discussing the possibility of a general strike, arguing that that would be "a possible idea at a time when the population is ready for it."[5]

The third section of the book, entitled "After thirty years of class war", comprises the text of an interview with Chomsky conducted at MIT on January 6, 2012, by a New York University student, Edward Radzivilovskiy].[6] Responding to Radzivilovskiy's questions, Chomsky lays out what the Occupy movement represents, and what its demands are, arguing that it is primarily a popular protest against income stagnation for the majority and the increasing concentration of wealth among an elite minority. He contrasts it with the Tea Party movement, which he argues only represents the interests of a small Euro-American minority, being backed by the corporate support that Occupy rejects. He then draws comparisons between Occupy and the Arab Spring, arguing that the latter had been far more successful in bringing down governments because it had the backing of organized labor movements, all of which had been decimated by corporate power in the U.S., and calls for a renewed revival of the American labor movement. Rejecting the idea that Occupy is an anarchist movement, he notes that its primary demands require reform rather than revolution, advocating governmental support for economic growth over austerity measures.[7]

Section four, "InterOccupy", contains the transcript of a conference call with Chomsky chaired by Mikal Kamil and Ian Escuela on January 31, 2012, in which he answered pre-selected questions from the Occupy community. Beginning with a discussion of the media coverage of Occupy, he moves on to discuss the police repression that the movement has faced, arguing that the best way to avoid such repression was to gain "active public support" for their cause. He considers one of the primary achievements of Occupy to have been to bring together communities to discuss and debate in a democratic forum, thereby rejecting the ideologies of selfishness proposed by the likes of Ayn Rand. Chomsky then discusses how to get the corporate sector out of politics and how to introduce greater democracy to the U.S. He rounds off this chapter with a discussion of the nature of the Republican and Democratic parties, the work of Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci and the role of the U.S. housing bubble in the global depression.[8]

Section five is titled "Occupying Foreign Policy", a question-and-answer session that Chomsky gave at the University of Maryland on January 27, 2012. Chomsky discusses how the Occupy movement could hope to influence and control the foreign policy of the United States, directing it away from its support for autocratic regimes and military interventionism. Proceeding to discuss the successes that popular protest have had in influencing government decisions, he argues that the protests of the 1930s led to the formation of the New Deal, and that the protests against the Iraq War – although unable to stop the conflict – helped to moderate the use of weaponry used by U.S. troops. Praising America Beyond Capitalism (2004), a book by the political economist Gar Alperovitz, he then discusses ways in which the Occupy movement can influence the public discourse into accepting and understanding their views and arguments.[9] This is followed by "Remembering Howard Zinn", Chomsky's reminiscences of his late friend Howard Zinn (1922–2010), a historian and social activist who authored the influential book, A People's History of the United States (1980).[10] Chomsky's text is then followed by "Occupy Protest Support", a set of legal advice for protesters facing arrest and prosecution authored by the National Lawyers Guild.[11]

Main arguments

What is the Occupy Movement?

"Primarily, I think [Occupy] should be regarded as a response, the first major public response, in fact, to about thirty years of a really quite bitter class war that has led to social, economic and political arrangements in which the system of democracy has been shredded."

In Occupy, Chomsky explores both the context to the Occupy movement, and highlights its primary aims. He describes it as a reaction by members of the working and middle classes to the "class war" that has been waged against them by the upper class who control the commercial sector since the 1970s. During those 30 years, Chomsky argues, the nation's wealth has become increasingly concentrated among a tiny percentage of the population, primarily those in control of the financial sector. Chomsky argues that this process has been furthered by government policies implemented by both the Republican and Democrat administrations, with both parties being financed by that same financial and commercial sector. According to Chomsky, while the wealth has been increasingly focused in the socio-economic elite who control the financial sector, the rest of the population have suffered higher workloads, unsustainable debt, a weakening benefits system and stagnating incomes and real wages, causing them to be "angry, frustrated, [and] bitter". It is this inequality, Chomsky argues, that has led to the Occupy movement.[13]

Chomsky states that the Occupy movement's demands are those of the majority of the U.S. population: to solve the problem of social inequality in the country. More specifically, he argues that their precise demands include greater regulation of financial transaction taxes, and reversing the rules of corporate governance that have led to the current situation. Nonetheless, he also argues that many Occupy members would be hesitant to directly state what their objectives are, because "they are essentially crafting a point of view from many disparate sources."[14]

How to spread Occupy and democratize society

Chomsky argues that the multi-party, representative, liberal democracy that governs the United States is insufficiently democratic, instead advocating a form of participatory, direct democracy through which the ordinary citizens have a direct say in public policy. As such, he advocates that communities take a different approach to the upcoming primary elections; instead of simply listening to speeches given by the politicians hoping to be elected, they should get together in democratic councils and discuss what issues they want addressing. That done, Chomsky argues, they should approach the politicians, informing them that they have no interest in their speeches, but that if they want to get elected, they must come and listen to the demands of the people; alternately, he argues, these communities should select their own representatives whom they could then vote for.[15]

"Making moves in the direction of real democracy is not utopian. These are things that can be done in particular communities. And it could lead to a noticeable change in the political system. Sure, we should get money out of politics, but that's going to take a lot of work. One way to go at it is just to elect your own representatives. It's not impossible."

Chomsky also argues for economic democratization, with the workers themselves controlling the means of production through worker cooperatives. As an example of how this might be achieved, he highlights the situation in 1977 when U.S. Steel decided to close down its facility in Youngstown, Ohio, leaving the steel workers unemployed; the local community attempted to purchase the factory from the company, and then run it as a "worker-run, worker-managed facility." They failed in their attempt, but Chomsky argues that had there been a sufficient amount of public support behind their cause – for instance like the Occupy protesters – then they might have succeeded. He noted a similar situation that occurred in a suburb of Boston in the early 21st century, when a multinational decided to close down a manufacturing facility because it was not producing sufficient profit. When the worker's trade union attempted to purchase the factory, the multinational refused, for reasons that Chomsky speculated were due to class consciousness.[17]

Chomsky also provides other suggestions for reforming the U.S. political system. He advocates health care reform and "reining in our crazed military system."[18] He also argues that in the time of economic recession, the government should focus on job creation and growth – just as they did in the 1930s with the New Deal – rather than on imposing unpopular austerity measures on the population.[19] He also describes it as important to rebuild an organized labor movement in the United States, in order to more effectively combat the domination of the ruling classes.[20]

Reception

Press reviews

The Foreign Policy in Focus's co-director John Feffer reviewed Occupy for the group's website, asserting that "What makes Chomsky's perspective so interesting, aside from the wealth of his political experience, is the range of his interests", evident through the way that he brings in examples from across the world. Ultimately, Feffer described the volume as a "valuable set of remarks and interviews".[21]

Writing in the New Statesman, George Eaton stated that he was surprised by the moderate stance that Chomsky took in Occupy, remarking that the "self-described anarchist sounds very much like a social democrat", offering the "cautious, provisional response one might expect from a Labour shadow cabinet minister" rather than the words of a radical revolutionary. Arguing that he was exhibiting "passionate sanity" at a time when much of the Left was gripped by conspiracy theories, he also criticized Chomsky for being "maddeningly banal" at points during the book, but ultimately thought that there was "much to commend Chomsky's radical pessimism."[3] In a brief review in The Independent, Arifa Akbar highlighted that although Chomsky's claims regarding class war carried with them "the ring of an old Marxist manifesto", the notion that we ourselves need to change in order to allow the state to change was "very contemporary".[22]

British Trotskyite publication, the Socialist Review, praised Chomsky's discussion of the impact of neoliberalism in the US, however they asserted that "when it comes to crucial questions - how do we fight and what are we fighting for - Chomsky's response is lacking." They assert that his claims that communities can challenge the Republican and Democrat domination of the electoral system are "somewhat bizarre" given that he has already established how "corrupt and biased" that system is. Criticising him for not looking at the concept of a potential revolution, they also express disagreement with his view that the "solution for the 99%" can be found within "the framework of capitalism".[23]

In The Coffin Factory literary magazine, Occupy was reviewed by Laura Isaacman, with Ruggiero's editor's note being described as a "powerful" introduction. Isaacram asserts that in this booklet, Chomsky "sets the record straight" in his own "tongue-in-cheek tone", following decades of being marginalized by the establishment.[24] Robert Thickett reviewed the book in August 2013 for the Mortgage Strategy website. He opined that Occupy felt "nostalgic", largely because the Occupy movement itself "has largely run out of steam." Nevertheless, he thought much of what Chomsky had to say was "practical" and that it was "difficult to refute much of what he says about the way Western society is set up."[25]

References

Footnotes

- ^ Matt Dellinger, "Sounds and Sites: Noam Chomsky", The New Yorker, Link Archived 2014-07-06 at the Wayback Machine, 3-31-03, accessed 1-26-09

- ^ Chomsky 2012. p. 121.

- ^ a b Eaton 2012.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. pp. 9–19.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. pp. 23–51.

- ^ "Edward Radzivilovskiy". Archived from the original on 2013-04-10. Retrieved 2012-11-17.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. pp. 53–67.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. pp. 69–88.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. pp. 91–103.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. pp. 104–111.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. pp. 115–120.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. p. 54.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. pp. 54–55.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. pp. 56–57.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. pp. 78–79.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. p. 48.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. pp. 34–37.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. pp. 48–49.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. p. 63.

- ^ Chomsky 2012. pp. 58–59.

- ^ Feffner 2012

- ^ Akbar 2012.

- ^ Joahill 2012.

- ^ Anon, The Coffin Factory, 2012.

- ^ Thicket 2013.

Bibliography

- "Review: Occupy by Noam Chomsky". The Coffin Factory. 23 May 2012. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- Akbar, Arifa (12 May 2012). "Occupy, By Noam Chomsky". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- Chomsky, Noam (2012). Occupy. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-241-96401-9.

- Eaton, George (9 May 2012). "Review: Occupy by Noam Chomsky". New Statesman. London. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- Feffer, John (6 April 2012). "Review: Noam Chomsky's "Occupy"". Foreign Policy in Focus. Washington D.C. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Joachill, Arnie (June 2012). "Occupy". International Socialism. No. 370. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Thickett, Robert (28 August 2013). "Media Spotlight: Occupy by Noam Chomsky". Mortgage Strategy. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2013.