O zittre nicht, mein lieber Sohn

"O zittre nicht, mein lieber Sohn" ("Oh, don't tremble, my dear son") is the first aria performed by the Queen of the Night (a famous coloratura soprano role) in Mozart's singspiel The Magic Flute (Die Zauberflöte). It is not as well known as the Queen's second aria, "Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen", though no less demanding; the aria requires a soprano coloratura with extremely high tessitura and great vocal flexibility.

Significance

The role of Queen of the Night demands a range that until Mozart's time was almost never called for, and this opened the door for later composers to call for specific kind of singers (lyric, dramatic, coloratura etc.), rather than just "soprano", "tenor" etc.[1]

The part, in whole, includes two arias, O zittre nicht and Der Hölle Rache. The first calls for a rather lyric and flexible voice while the second requires a dramatic and powerful voice. Originally, the part was written for Josepha Hofer, the composer's sister-in-law, whose voice possessed both of these qualities. Most modern performers are specialists in either lyric or dramatic style. This, along with the difficulty of the two arias, makes the role of the Queen of the Night one of the most demanding in operatic repertoire.

Context in the opera

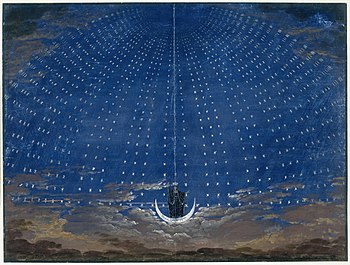

In the preceding scene, Prince Tamino was shown a portrait of the Queen's daughter Pamina and fell instantly in love with her, singing of his feelings in the aria "Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön". The Queen then makes a dramatic entrance, preceded by the Three Ladies calling to Tamino "Sie kommt! Sie kommt!" ("[Here] she comes!"). The grand entrance music for the Queen is in B-flat, marked Allegro maestoso, with the following stage direction:

The mountains [in the scenery] are parted, and the stage is transformed into a magnificent chamber. The Queen is seated on a throne adorned with shining stars.[2]

Not all modern productions adhere to this prescription.

In the aria, the Queen first quiets Tamino's fears and attempts to befriend him, then tells the sad, although misleading, tale of Pamina's abduction by Sarastro, and finally makes a stirring plea to Tamino to rescue her daughter. As the aria ends, the Queen and the Three Ladies leave the stage, leaving the astonished Tamino to ponder his task and gather his resolve. A performance takes about five minutes.

Libretto

The verse to which the aria was set was written by the opera's librettist Emanuel Schikaneder. Schikaneder was the impresario for whom the opera was written as well as the first performer of the role of Papageno.

O zittre nicht, mein lieber Sohn,

du bist unschuldig, weise, fromm

Ein Jüngling so wie du, vermag am besten,

dies tiefbetrübte Mutterherz zu trösten.

Zum Leiden bin ich auserkoren,

denn meine Tochter fehlet mir.

Durch sie ging all mein Glück verloren,

ein Bösewicht, entfloh mit ihr.

Noch seh' ich ihr Zittern

mit bangem Erschüttern,

ihr ängstliches Beben,

ihr schüchternes Streben.

Ich mußte sie mir rauben sehen.

"Ach helft!" – war alles was sie sprach

allein vergebens war ihr Flehen,

denn meine Hilfe war zu schwach.

Du wirst sie zu befreien gehen,

du wirst der Tochter Retter sein!

Und werd' ich dich als Sieger sehen,

so sei sie dann auf ewig dein.

Oh, don't tremble, my dear son!

You are innocent, wise, pious;

A youth like you is best able

to console this deeply troubled mother's heart.

I am chosen for suffering

For my daughter is gone from me;

Through her all my happiness has been lost,

A villain, fled with her.

I can still see her trembling

with fearful shaking,

her frightened quaking,

her timid effort.

I had to see her stolen from me.

"Oh help!" – was all that she said

But in vain was her pleading,

For my powers of help were too weak.

You will go to free her,

You will be my daughter's savior.

And if I see you return in triumph,

Let her then be yours forever.

There are five quatrains, of which the third is written in amphibrachic dimeter and the remaining ones in iambic tetrameter, which is the normal meter for The Magic Flute. Mozart repeats the words "ach helft!" ("Oh, help!") and "Du" ("you", three times), so the lines with these words are not iambic tetrameters as they are actually sung. The rhyme scheme is [AABB][CDCD][EEFF][GHGH][IJIJ].

Music

The soprano soloist (vocal range: D4 to F6) performs with an orchestra consisting of pairs of oboes, bassoons, horns in B♭, and strings. The three parts of the Queen's discourse are set as musically separate items, each marked by a change in key:

- Recitative (B-flat major) – continues the Allegro maestoso tempo marking of the entrance music, but often performed in free tempo

- First part of the aria (G minor) – Andante

- Second part of the aria (back to B-flat major) – Allegro moderato

It is in the third part that the music reaches a high level of virtuosity for the soloist, including the following very difficult coloratura:

It can be seen that Mozart aligned the text (dann) to give the singer the most sonorous and singable vowel "a" for most of the passage.

The highest note, F6, is claimed by a posthumous witness to have been mentioned by Mozart on his deathbed; the composer was (if the story is true) imagining his sister-in-law's performance. See Death of Mozart.

Critical opinion

While countless audiences have enjoyed hearing skilled sopranos navigate the difficult coloratura passage, Spike Hughes detects a more significant purpose in Mozart's writing:

The coloratura, which is never overdone for a moment in this aria, has a tremendous dramatic impact. It is not intended as a display of a singer's vocal prowess but of the Queen's character and as [in] Die Entführung ... coloratura is often synonymous in Mozart's mind with resolution and anger.[3]

References

- ^ Coffin, Berton (1960). Coloratura, Lyric and Dramatic Soprano, Vol. 1. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8108-0188-2.

- ^ Dover edition (1985, 41). Original German: Die Berge teilen sich auseinander, und das Theater verwandelt sich in ein prächtiges Gemach. Die Königin sitzt auf einem Thron, welcher mit transparenten Sternen geziert ist. (Source: NMA edition, linked below)

- ^ Hughes, Spike (1972) Famous Mozart operas. New York: Dover, p. 203.

External links

- O zittre nicht, mein lieber Sohn: Score in the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe

- Audio on YouTube, Cheryl Studer, Academy of St Martin in the Fields, Neville Marriner

- Audio on YouTube, Wilma Lipp, WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne, Joseph Keilberth