Jarrah Forest

| Jarrah Forest Southwest Australia woodlands | |

|---|---|

Jarrah Forest near Pemberton in 2008 | |

The IBRA regions, with Jarrah Forest in red | |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Australasian |

| Biome | Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub |

| Borders | |

| Geography | |

| Area | 46,150 km2 (17,820 sq mi) |

| Country | Australia |

| state | Western Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°29′28″S 117°01′41″E / 33.491°S 117.028°E |

| Conservation | |

| Protected | 12.86%[1] |

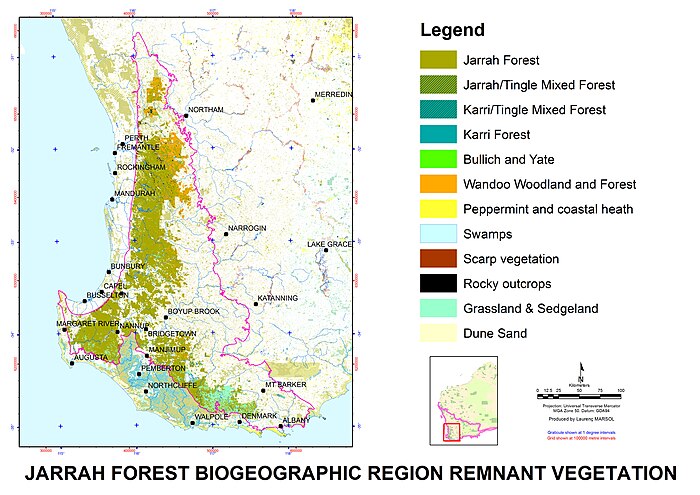

Jarrah Forest, also known as the Southwest Australia woodlands, is an interim Australian bioregion and ecoregion located in the south west of Western Australia.[2][3] The name of the bioregion refers to the region's dominant plant community, jarrah forest – a tall, open forest in which the dominant overstory tree is jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata).[4]

Jarrah Forest is recognised globally as a significant hotspot of plant biodiversity and endemism, and is also managed for land uses such as water, timber and mineral production, recreation, and conservation.[5][6][7]

Location and description

The bioregion stands on the 300-metre-high (980 ft) Yilgarn block inland plateau and includes wooded valleys such as those of Western Australia's Murray River and the Helena River. The Darling Scarp forms the western edge of the plateau, and the Swan Coastal Plain lies between the scarp and the coast. The scarp generally forms the western boundary of the bioregion, although it extends to the west coast at Cape Naturaliste. At the southern end of the plateau is the Whicher Range and inland is the lower Blackwood Plateau. The south eastern interior of the region includes the peaks of the Stirling Range, now preserved within Stirling Range National Park.

Soils in the jarrah forest are infertile, especially for phosphorus, and are often salt-laden.

The bioregion covers an area of 4,509,074 hectares (11,142,160 acres). It is divided into two sub-regions, Northern Jarrah Forest (1,898,799 hectares (4,692,030 acres)) and Southern Jarrah Forest (2,610,275 hectares (6,450,130 acres)).

The Swan Coastal Plain bioregion lies to the west below the scarp. The Warren bioregion, also known as the Jarrah-Karri forest and shrublands, is to the south. The Avon Wheatbelt bioregion, part of the Southwest Australia savanna ecoregion, is to the east.

Climate

The area has a warm Mediterranean climate, with more annual rainfall (1,300 millimetres (51 in)) on the scarp than inland or to the north-east (700 millimetres (28 in)).[8]

Flora

Jarrah Forest is unique in that it shares the co-dominate Corymbia species Marri (Corymbia calophylla).[5][4] Marri, formerly formally known as Eucalyptus calophylla, is a prevalent canopy species and the jarrah forest is commonly called jarrah-marri forest.[9] Other eucalypts are present but in much less abundance. The Southern Jarrah Forest contains extensive areas of wetland vegetation in the south–east, dominated by paperbarks including the swamp paperbark (Melaleuca rhaphiophylla), and other eucalypts such as the swamp yate (Eucalyptus occidentalis) and the Albany blackbutt (Eucalyptus staeri).[10][5]

The eastern forest is largely wandoo woodland, dominated by the canopy species wandoo (Eucalyptus wandoo), and, on breakaways, powderbark (also known as powderbark wandoo) (Eucalyptus accedens).[9][10] Other eucalypts in these eastern areas include York gum (Eucalyptus loxophleba).[9] The upland areas are particularly rich in plant life, while the drier inland plateau is less so. The wetter valleys with fertile soils contain flooded gum (Eucalyptus rudis), bullich (Eucalyptus megacarpa) and blackbutt (Eucalyptus patens).[9] Heath is a common understorey of the jarrah forest in the north and east.[8]

The smaller trees commonly found in Jarrah Forest include bull banksia (Banksia grandis), sheoak (Allocasuarina fraseriana), snottygobble (Persoonia longifolia) and woody pear (Xylomelum occidentale).[11] Rare plants within Jarrah Forest include orchid species Drakaea confluens and Caladenia bryceana, and Baumea reed beds are unique to the forest and adjacent areas.[10]

Fauna

Jarrah Forest supports 29 mammal, 150 bird, and 45 reptile species.[12] Mammals include the numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus), Gilbert's potoroo (Potorous gilbertii), western quoll or chuditch (Dasyurus geoffroii), woylie (Bettongia penicillata), tammar wallaby (Notamacropus eugenii), western ringtail possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis), common brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula), quenda or western brown bandicoot (Isoodon fusciventer), and red-tailed phascogale (Phascogale calura).[5][8][10] Most of these were once widespread vertebrate species but are now limited to the fragmented portions of Jarrah Forest.[5][13]

The chuditch, before the introduction of large mammalian pest species, was the largest carnivorous marsupial in south-west Western Australia, distributed across 70% of mainland Australia.[14] It now inhabits only 2% and is listed as 'Vulnerable' under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act of 1999.[15][14] For species such as the brushtail possum, population decline has not been extensive as they will colonise older restored minesites.[13]

Carnaby's black cockatoo (Zenda latirostris) is endemic to south-west Western Australia and is listed as endangered under the EPBC of 1999.[15] Other birds to inhabit Jarrah Forest include rare birds such as the forest red-tailed black cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus banksii naso), Muir's corella (Cacatua pastinator pastinator), black-throated whipbird (Psophodes nigrogularis), western bristlebird (Dasyornis longirostris), noisy scrub-bird (Atrichornis clamosus) and Baudin's black cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus baudinii).[8][16]

Reptiles inhabiting Jarrah Forest include legless lizards, dragon lizards, skinks, blind snakes, pythons and venomous snakes.[12] The western bearded dragon (Pogona minor) was found in restored forest rather than old growth forest.[12][17]

Amphibians found in the northern sector of Jarrah Forest include the rare white-bellied frog (Geocrinia alba), yellow-bellied frog (Geocrinia vitellina) and sunset frog (Spicospina flammocaerulea).[8] Endemic frogs inhabit the southern sector of Jarrah Forest such as the small western froglet (Crinia subinsignifera) and the western marsh frog (Heleioporus barycragus).[10]

Diverse invertebrate fauna communities are also present within Jarrah Forest. Many of these invertebrate species are responsible for nutrient recycling, an essential element of Western Australia's biodiversity.[18][19][20] In particular, the insect group Apocrita, which includes wasps, bees, and ants, are a keystone group that, through predation and parasitism, keep other invertebrate populations controlled.[19] The loss of Apocrita could be detrimental to the invertebrate community and to the jarrah forest ecosystem.[19] Rare and endandered native bees include Leioproctus douglasiellus and Neopasiphae simplicior.[8]

History

The first evidence of human habitation of the region was 50,000 years ago at Devil's Lair by ancestors of today's Aboriginal people.[21]

The Noongar are the Aboriginal inhabitants of the bioregion. The Noongar comprised 14 groups, which spoke distinct but mutually-intelligible languages. Aboriginal populations were generally denser on the coastal plain and along the coastal forest edge, and in the interior woodlands and shrublands, particularly near permanent streams and river estuaries. Population was sparse in the forested areas of the south.[21]

The Aboriginal inhabitants deliberately set fires to manage the land and vegetation. Evidence from lake and estuarine sediments and firsthand accounts suggest that fire intervals in well-settled areas were frequent – from one to ten years – compared to unoccupied forests and offshore islands, where fire intervals were 30 to 100 or more years. Frequent burning reduced woody cover and encouraged the growth of low shrubs, herbs, and grasses, fostering open woodlands, shrublands, and savannas and limiting areas of dense forest and thicket.[21]

Settlement of the region by Europeans began in the 19th century. Forests were logged for timber, and areas cleared for agriculture and pasture. The Noongar were dispossessed from much of the land, and the fire regime changed from one of deliberately-set low-intensity fires to one of general fire suppression, with accidental or lightning-set fires which are less frequent but often more intense.

Jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata) is considered one of the best general purpose hardwoods in the world. The British started logging the jarrah forest in the 1840s to produce timber for use in construction, transport and power, and to protect water supplies.[22] Logging was largely unregulated until the release of the Forests Act of 1918.[5] The following 50 years saw forest management expand to include water quality and yield, soil management, rehabilitation of mined forest, recreation and nature conservation.[5] Jarrah was harvested for woodchips as well as high quality furniture and flooring until the WA government responded to decades of campaigning by placing a ban on native forest logging in 2024.[23]

Environmental threats

Most of Jarrah Forest has been cleared for agriculture, timber and mining, leading to the consequent degradation of flora and fauna species and ecosystems.[13] The areas managed for forest production have been logged two to three times such that this forest bears no resemblance to the original forest. This is further threatened by broad scale bauxite mining and the replacement of native vegetation with exotic grasses and weeds, introduced grazing species and predators such as the fox (Vulpes vulpes).[13][24] Native flora also suffers from disease and exploitation of water sources for agriculture. Less anthropological threats include periodic wildfire, pathogens, variable climate and outbreaks of defoliating insects.[25]

Introduced species

The significant population loss of fauna species in Jarrah Forest is attributed to the fox and cat (felis catus).[13] Predators can influence abundances and ranges of species at all trophic levels, including primary producers, prey and other predators.[14] Between 1933 and 1944 the terrestrial range of the quokka (Setonix brachyurus), the woylie, the chuditch, the brushtail possum, the western ringtail possum, the tammar wallaby and the numbat contracted quite dramatically.[24] This was blamed on the fox. Population numbers, however, of woylies and boodies were already declining in 1911, most likely due to cats (Felis catus) introduced by Europeans.[24] Another introduced species that is a major threat to birds in some areas of Jarrah Forest, but for a very different reason, is the feral bee (Apis mellifera).[26] Swarms of feral bees take over tree hollows, stealing the nesting sites of hollow-nesting birds.[26]

Habitat loss and fragmentation

Landscape fragmentation and the loss of suitable macro- and microhabitats can be detrimental to an animal's ability to live in or traverse through an area.[27] The range of the western quoll has dramatically reduced since European settlement.[27] With matrix permeability greatly reduced this wide-ranging carnivore is highly susceptible to being hit by vehicles as it crosses road reserves moving from one area to another.[27] The roadkill count of fauna in general on bauxite mines fringing Jarrah Forest is high.[27] Despite the restoration and protection of jarrah forest in areas previously used by mine sites, the lack of hollow logs and stumps on the ground is evident.[13] Low understory cover, low plant species richness and relatively low biomass are all problems associated with protected restored jarrah forest.[13] Suitable habitats can take decades to form and animals that rely on these for shelter, such as the chuditch and Egernia napoleonis, are left without.[12][13] Similarly birds that nest in tree hollows will not do so until trees are big enough and old enough to have sufficient hollows.[13] Jarrah is a slow growing species and 130 years can be considered the minimum age for the development of appropriate hollows in jarrah and marri.[26][28]

The loss of forest for agriculture and timber has resulted in diminishing population numbers of many fauna species.[7][13] Nine mammal and seventeen bird species are obligate users of tree hollows.[28] Species that use large hollows usually have a relatively small home range and depend on their hollows for breeding.[29] These species are most likely to be negatively impacted by logging.[29] Roost sites (hollows) are critical for the persistence of insectivorous bats living in Jarrah Forest.[28][30] Spending a large portion of their lives in roosts, they are used as diurnal shelters, shelter during maternity, and shelter for bachelors, migrating and hibernation sites.[30] Facilitating complex social interactions including information transfer, roost sites also act as breeding sites, they provide protection from bad weather and predators, they minimise parasite load and promote energy conservation.[30]

Mining

Mining in the Jarrah Forest has caused further habitat loss and fragmentation to the local environment, as well as being the source of several controversies. In November 2023, 154 Australian scientists part of the Leeuwin Group of Scientists condemned continued mining in the northern area, particularly by Alcoa, and accused the American company of not completely rehabilitating bauxite mines.[31] Alcoa had handed back areas of its original bauxite mine in Jarrahdale in 2005 and 2007.[32] The group's claim that Alcoa was clearing 8 square kilometres (2,000 acres) each year was denied by Alcoa, with Alcoa refuting the group's criticism.[33] Along with concerns that Alcoa's operations could impact the drinking supply of Serpentine Dam, WA's Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) began looking into the company's operations and impacts.[34] In December 2023, Premier Roger Cook began stricter control over Alcoa's mining operations ahead of the EPA's decision.[35]

Disease

Prevalent in the northern areas of Jarrah Forest, dieback disease, caused by the introduced soil-borne pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi, is a serious threat to many plant species.[5][36] The disease involves the formation of lesions (decaying tissue) starting in the roots and moving up the stem of a plant, and, in the case of many species, killing them.[37] It negatively affects more than 22% of the plant species in the forest.[38] P. cinnamomi has been found in suberized and partially suberized roots that are perennial and it is these roots that form the specialised feeder root system of the jarrah.[39] The spread of dieback is exacerbated by altered drainage caused by mining and timber harvesting.[5] The soil population of P. cinnamomi is generally highest during spring, the time of year when soil temperature and moisture levels are high.[39] An increase in summer rainfall is likely to increase the harm that this pathogen causes in the northern and southern jarrah forests, with high mortality rates of jarrah expected.[26]

Management

FORESTCHECK is a Department of Parks and Wildlife initiative that is responsible for monitoring biodiversity in the jarrah forests of south-west Western Australia. Monitoring total species richness, abundance and composition FORESTCHECK is designed to provide forest managers with accurate accounts of changes and trends in biodiversity associated with management activities.[5] FORESTCHECK use four Jarrah Forest ecosystems that reflect four different management systems: old-growth forest that has not been harvested or at least not in the last 40 years, coupe buffers (temporarily unharvested forest between harvested areas), shelterwood forest and forest receiving gap release treatment.[5][40] Shelterwood forest limits logging to a residual basal area of c. 13m2ha-1 and gap release treatment to a residual basal area of c. 6m2ha-1.[26] These are surrounded by an unlogged coupe buffer of approximately 100m.[26] Focussing on timber harvesting and silviculture treatments in the present, future monitoring programs may be extended to include fire, climate change, mining, utility corridors and recreational use.[5] Silviculture is a practice carried out in restored areas of Jarrah Forest.[5] It aims to promote growth of retained trees, to enable the growth of young regeneration trees without having to compete with the overstory, to establish seeding regeneration and to retain and promote flora species and individuals in forests infested by dieback.[5] Disease-loss appraisal is critical in developing economic and rational management strategies for dieback.[36]

The benefits of using biological controls and fungicides have been explored in the management of P. cinnamomi. Fifteen native Western Australian legumes were tested for their effectiveness as biological control agents against the pathogen. Five species showed high potential and by manipulating rehabilitation seed mix ratios could be used to suppress the pathogen.[41] The fungicide phosphite has been found to be effective treatment against P. cinnamomi, especially when applied before a plant is infected. The fungicide can be applied after infection, however the greater the time between infection and treatment, the less effective it will be.[38] It is difficult to estimate the cost of plant disease in conservation areas; loss of conservation values cannot be given monetary value.[36] However, the cost of controlling the disease can. It was estimated that the control of P. cinnamomi in 1989 cost the Western Australian Government at least $3.4 million.[36] Disease management plans focus on minimising the spread of the mould by restricting movement of propagules in soil and by translocating plant species from infected sites to healthy sites.[5][36]

Vertebrate fauna play a key role in jarrah forest ecosystem processes including pollination, grazing and predation.[13] The chuditch, quenda and common brushtail possums are three such species considered essential in the development of a sustainable restored forest ecosystem.[13] To prevent population numbers of these species and other vertebrates from further declining an aerial fox baiting program was introduced forest-wide.[29][13]

Management practices carried out to ensure the persistence of hollow-using species include protecting old growth jarrah forest and keeping extensive areas of forest reserved from logging.[29][30] In the sections of jarrah forest are available to timber harvesting, science-based prescriptions have been implemented delegating those trees that are to be retained.[29][30]

Protected areas

12.86% of the ecoregion is in protected areas.[1] Protected areas are managed for uses including recreation and conservation.[29] There are many small areas of parkland, and larger protected areas include the Dryandra Woodland and the Perup Forest Ecology Centre. The Walpole Wilderness Area, which was established in 2004, includes several national parks that cover a portion of the southern Jarrah Forest and the Jarrah-Karri forest and shrublands to the south. Lane Poole Reserve is the largest reserve in the Northern Jarrah Forest.[42] There are few large and secure reserves such as national parks and nature reserves in the northern jarrah region where the best forest occurs. Much of this region is under long-term mining leases for bauxite owned by Alcoa and Worsley who have actively resisted attempts to allow the WA government to create substantial and secure reserves.[5]

Protected areas include:[1]

- Beelu National Park

- Blackwood River National Park

- Boyndaminup National Park

- Bramley National Park

- Dalgarup National Park

- Dryandra Woodland National Park

- Easter National Park

- Gooseberry Hill National Park

- Greater Kingston National Park

- Greater Preston National Park

- Greenmount National Park

- Hassell National Park

- Helena National Park

- Hilliger National Park

- John Forrest National Park

- Kalamunda National Park

- Korung National Park

- Lake Muir National Park

- Lake Muir Nature Reserve

- Lane Poole Reserve

- Lesmurdie Falls National Park

- Midgegooroo National Park

- Milyeannup National Park

- Mount Frankland North National Park

- Mount Lindesay National Park

- Mount Roe National Park

- Porongurup National Park

- Serpentine National Park

- Shannon National Park

- Stirling Range National Park

- Wandoo National Park

- Walyunga National Park

- Waychinicup National Park

- Wellington National Park

- Whicher National Park

- Wiltshire-Butler National Park

- Yelverton National Park

Benefits of protection

Unlogged buffers and old growth forest contain high densities of trees with appropriate hollows for roosting, where gap release and shelterwood areas do not.[30] Mature forest is essential to the development of tree hollows and the prescribed retention of the largest trees will significantly improve the chances of large species such as the red-tailed black cockatoo and the common brushtail possum inhibiting appropriately sized tree hollows.[28]

The implementation of the fox baiting program was expected to greatly increase the population numbers and range of native including the western ringtail possum which was re-introduced into the jarrah forest in the same time-frame.[28] The abundance and distribution of the chuditch population in south-west WA has recovered quite significantly in the last decade and this has been attributed to the control of foxes.[43] Within two to three years of the aerial baiting program mammal species numbers increased.[13] Capture rates (interpreted as mammal abundance) of the woylie, chuditch and common brushtail possum coincided with the efforts of this program.[24] In 1974-1999 six mammals were listed as threatened under Australian Commonwealth and WA stage legislation, the woylie, tammar wallaby, quenda, chuditch, numbat and the western ringtail possum. Now, the quenda and the tammar wallaby are no longer classified as a threatened species.[12][24]

Studies of reptiles in Jarrah Forest show that the older a rehabilitated forest is, the greater the number of reptile species will be present.[12] Species requiring particular habitats such as exfoliating bark (gecko Phyllodactylus marmoratus) or deep leaf litter (blind snake Ramphotyphlops australis) were not present in rehabilitated sites that were eight years old, but were present in those greater than twelve years old.[12] Similarly, various rehabilitated sites were monitored and black cockatoos were found feeding only in rehabilitated forests established eight or more years ago, the time needed for food resources to become available.[44] Birds rapidly colonise and 95% of species found in old growth Jarrah Forest are now in rehabilitated forests ten years or older.[13] The protection of old growth jarrah forest needs to continue, especially in the northern region and the best way to achieve this is to claw back some of the mining lease areas granted to Alcoa and Worsley and create substantial reserves with proper A Class status. Additionally jarrah forest needs to be rehabilitated to promote further growth, decrease fragmentation and to maintain and improve flora and fauna biodiversity, a process that may take decades.[44]

Further reading

- Dell, B., J.J. Havel, and N. Malajczuk (editors) (1989) The Jarrah Forest : a complex mediterranean ecosystem Dordrecht ; Boston : Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 90-6193-658-6

- Thackway, R and I D Cresswell (1995) An interim biogeographic regionalisation for Australia : a framework for setting priorities in the National Reserves System Cooperative Program Version 4.0 Canberra : Australian Nature Conservation Agency, Reserve Systems Unit, 1995. ISBN 0-642-21371-2

References

- ^ a b c "Southwest Australia woodlands". DOPA Explorer. Accessed 30 April 2022. [1]

- ^ Environment Australia. "Revision of the Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA) and Development of Version 5.1 - Summary Report". Department of the Environment and Water Resources, Australian Government. Archived from the original on 3 September 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ IBRA Version 6.1 data

- ^ a b Koch, J. M., & Samsa, G. P. (2007). Restoring Jarrah forest trees after bauxite mining in Western Australia. Restoration Ecology, 15(s4), S17-S25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p McCaw, W. L., Robinson, R. M., & Williams, M. R. (2011). Integrated biodiversity monitoring for the jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata) forest in south-west Western Australia: the FORESTCHECK project. Australian Forestry, 74(4), 240-253.

- ^ Rix, M. G., Edwards, D. L., Byrne, M., Harvey, M. S., Joseph, L., & Roberts, J. D. (2015). Biogeography and speciation of terrestrial fauna in the south‐western Australian biodiversity hotspot. Biological Reviews, 90(3), 762-793.

- ^ a b Whitford, K. R. (2002). Hollows in jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata) and marri (Corymbiacalophylla) trees: I. Hollow sizes, tree attributes and ages. Forest Ecology and Management, 160(1), 201-214.

- ^ a b c d e f Williams, Kim; Mitchell, Dave (September 2001). "Jarrah Forest 1 (JF1 – Northern Jarrah Forest subregion)" (PDF). A Biodiversity Audit of Western Australia’s 53 Biogeographical Subregions in 2002. The Department of Conservation and Land Management. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Biodiversity and Vegetation - Jarrah Forest". Australian Natural Resources Atlas - Natural Resource Topics. Australian Government. 15 June 2009. Archived from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Hearn, Roger; Williams, Kim; Comer, Sarah; Brett Beecham (January 2002). "Jarrah Forest 2 (JF2 – Southern Jarrah Forest subregion)" (PDF). A Biodiversity Audit of Western Australia’s 53 Biogeographical Subregions in 2002. The Department of Conservation and Land Management. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ Koch, J. M. (2007). Restoring a jarrah forest understorey vegetation after bauxite mining in Western Australia. Restoration Ecology, 15(s4), S26-S39.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nichols, O. G., & Nichols, F. M. (2003). Long‐Term Trends in Faunal Recolonization After Bauxite Mining in the Jarrah Forest of Southwestern Australia. Restoration Ecology, 11(3), 261-272.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Nichols, O. G., & Grant, C. D. (2007). Vertebrate fauna recolonisation of restored bauxite mines—key findings from almost 30 years of monitoring and research. Restoration Ecology, 15(s4), S116-S126.

- ^ a b c Morris, K., Johnson, B., Orell, P., Gaikhorst, G., Wayne, A., & Moro, D. (2003). Recovery of the threatened chuditch (Dasyurus geoffroii): a case study. Predators with Pouches: The Biology of Carnivorous Marsupials. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, 435-451.

- ^ a b Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (Austl.).

- ^ Abbott, I. (1998). Conservation of the forest red-tailed black cockatoo, a hollow-dependent species, in the eucalypt forests of Western Australia. Forest Ecology and Management, 109(1), 175-185.

- ^ Craig, M. D., Stokes, V. L., Hardy, G. E., & Hobbs, R. J. (2015). Edge effects across boundaries between natural and restored jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata) forests in south‐western Australia. Austral Ecology, 40(2), 186-197.

- ^ Grant, C. D., Ward, S. C., & Morley, S. C. (2007). Return of ecosystem function to restored bauxite mines in Western Australia. Restoration Ecology, 15(s4), S94-S103.

- ^ a b c Heath, M., Ladd, P., & Davis, J. (2007). The effect of prescribed burning on the leaf litter invertebrates of the jarrah forest, with special reference to Apocrita (Insecta: Hymenoptera).

- ^ Majer, J. D., Brennan, K. E., & Moir, M. L. (2007). Invertebrates and the restoration of a forest ecosystem: 30 years of research following bauxite mining in Western Australia. Restoration Ecology, 15(s4), S104-S115.

- ^ a b c "Hassell, Cleve W., and Dodson, John R. (2003). "The fire history of south-west Western Australia prior to European settlement in 1826-1829". in Fire in ecosystems of south-west Western Australia:Impacts and management. Ian Abbott and Neil Burrows, eds. Backhuys Publishers, 2003, pp. 71–85.

- ^ Abbott, I., Mellican, A., Craig, M. D., Williams, M., Liddelow, G., & Wheeler, I. (2003). Short-term logging and burning impacts on species richness, abundance and community structure of birds in open eucalypt forest in Western Australia. Wildlife Research, 30(4), 321-329.

- ^ Hardinge, Alice; Beckerling, Jess (16 January 2024). "Campaigns to End Logging in Australia (Commons Conversations Podcasts)". The Commons Social Change Library. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Burrows, N. D., & Christensen, P. E. S. (2002). Long-term trends in native mammal capture rates in a jarrah forest in south-western Australia. Australian Forestry, 65(4), 211-219.

- ^ Farr, J. D., Wills, A. J., Van Heurck, P. F., Mellican, A. E., & Williams, M. R. (2011). Forestcheck: the response of macro-invertebrates to silviculture in jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata) forest. Australian Forestry, 74(4), 315-327.

- ^ a b c d e f Abbott, I., Liddelow, G. R. A. E. M. E., Vellios, C. H. R. I. S., Mellican, A. M. A. N. D. A., & Williams, M. A. T. T. H. E. W. (2009). Monitoring bird populations after logging in forests of south-west Western Australia: an update from two long-term experimental research case studies. Conservation Science Western Australia, 7(2), 301-347.

- ^ a b c d McGregor, R. A., Stokes, V. L., & Craig, M. D. (2014). Does forest restoration in fragmented landscapes provide habitat for a wide‐ranging carnivore?. Animal Conservation, 17(5), 467-475.

- ^ a b c d e Whitford, K. R., & Williams, M. R. (2002). Hollows in jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata) and marri (Corymbiacalophylla) trees: II. Selecting trees to retain for hollow dependent fauna. Forest Ecology and Management, 160(1), 215-232.

- ^ a b c d e f Abbott, I., & Whitford, K. (2002). Conservation of vertebrate fauna using hollows in forests of south-west Western Australia: strategic risk assessment in relation to ecology, policy, planning, and operations management. Pacific Conservation Biology, 7(4), 240-255.

- ^ a b c d e f Webala, P. W., Craig, M. D., Law, B. S., Wayne, A. F., & Bradley, J. S. (2010). Roost site selection by southern forest bat Vespadelus regulus and Gould's long-eared bat Nyctophilus gouldi in logged jarrah forests; south-western Australia. Forest Ecology and Management, 260(10), 1780-1790.

- ^ Dee, Mel (30 November 2023). "Scientists take on mining giant". Your Local Examiner. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ Grant, Carl; Koch, John (2007). "Decommissioning Western Australia's First Bauxite Mine: Co‐evolving vegetation restoration techniques and targets". Ecological Management & Restoration. 8 (2): 92–105. doi:10.1111/j.1442-8903.2007.00346.x. ISSN 1442-7001.

- ^ "Scientists urge Alcoa and WA government to avoid 'extinction catastrophe' and stop mining in jarrah forests". ABC News. 27 November 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ "ABC alcoa jarrah forest". Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ "New framework to strengthen Alcoa's environmental approvals | Western Australian Government". www.wa.gov.au. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Shearer, B. L., Crane, C. E., & Cochrane, A. (2004). Quantification of the susceptibility of the native flora of the South-West Botanical Province, Western Australia, to Phytophthora cinnamomi. Australian Journal of Botany, 52(4), 435-443.

- ^ Tippett, J. T., Hill, T. C., & Shearer, B. L. (1985). Resistance of Eucalyptus spp. to invasion by Phytophthora cinnamomi. Australian Journal of Botany,33(4), 409-418.

- ^ a b Jackson, T. J., Burgess, T., Colquhoun, I., & Hardy, G. S. (2000). Action of the fungicide phosphite on Eucalyptus marginata inoculated with Phytophthora cinnamomi. Plant Pathology, 49(1), 147-154.

- ^ a b Shea, S. R., Gillen, K. J., & Leppard, W. I. (1980). Seasonal variation in population levels of Phytophthora cinnamomi Rands in soil in diseased, freely-drained Eucalyptus marginata Sm sites in the northern Jarrah forest of South-Western Australia. Protection Ecology, 2(2), 135-156.

- ^ Robinson, Richard. "The FORESTCHECK project: Integrated biodiversity monitoring in jarrah forest" (PDF). Department of Parks and Wildlife. Department of Environment and Conservation. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ D’Souza, N. K., Colquhoun, I. J., Sheared, B. L., & Hardy, G. S. J. (2005). Assessing the potential for biological control of Phytophthora cinnamomi by fifteen native Western Australian jarrah-forest legume species. Australasian Plant Pathology, 34(4), 533-540.

- ^ "Lane Poole Reserve". Parks and Wildlife Service, Government of Western Australia. Accessed 1 May 2022. [2]

- ^ Glen, A. S., De Tores, P. J., Sutherland, D. R., & Morris, K. D. (2010). Interactions between chuditch (Dasyurus geoffroii) and introduced predators: a review. Australian Journal of Zoology, 57(5), 347-356.

- ^ a b Lee, J., Finn, H., & Calver, M. C. (2010). Mine-site revegetation monitoring detects feeding by threatened black-cockatoos within 8 years. Ecological management & restoration, 11(2), 141-143.