North British Railway

| |

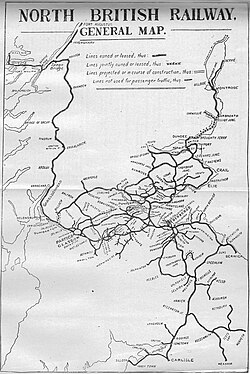

1920 map of the railway | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Edinburgh |

| Locale | Scotland |

| Dates of operation | 1844–1923 |

| Successor | London and North Eastern Railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 1,378 miles 3 chains (2,217.7 km) (1919)[1] |

| Track length | 2,748 miles 26 chains (4,423.0 km) (1919)[1] |

The North British Railway was a British railway company, based in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was established in 1844, with the intention of linking with English railways at Berwick. The line opened in 1846, and from the outset the company followed a policy of expanding its geographical area, and competing with the Caledonian Railway in particular. In doing so it committed huge sums of money, and incurred shareholder disapproval that resulted in two chairmen leaving the company.

Nonetheless, the company successfully reached Carlisle, where it later made a partnership with the Midland Railway. It also linked from Edinburgh to Perth and Dundee, but for many years the journey involved a ferry crossing of the Forth and the Tay. Eventually the North British built the Tay Bridge, but the structure collapsed as a train was crossing in high wind. The company survived the setback and opened a second Tay Bridge, followed soon by the Forth Bridge, which together transformed the railway network north of Edinburgh.

Early on, mineral traffic became dominant and brought in much more revenue than the passenger services.

At the grouping of the railways in 1923, the North British Railway was the largest railway company in Scotland, and the fifth largest in the United Kingdom. In that year it became a constituent of the new London and North Eastern Railway.

First steps

Early railways in Scotland had been mainly involved with conveyance of minerals, chiefly coal and limestone in the earliest times, a short distance to a river or coastal harbour for onward transport. The opening of the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway (E&GR) in 1842 showed that a longer distance general purpose railway could be commercially successful.

During the construction of the E&GR, the money market had eased somewhat and a rapid development of long-distance railways took place in England. Scottish promoters began to consider how central Scotland could be connected to the growing English network, and a government commission was established to determine the approved route. It was assumed for some time that only a single route was commercially viable. The commission, the Smith-Barlow Commission, deliberated for some time and presented an ambiguous report, and public opinion had moved on: numerous schemes for railways were proposed, not all of them practicable.

| North British Railway 1844 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for making a Railway from the City of Edinburgh to the Town of Berwick-upon-Tweed, with a Branch to the Town of Haddington. |

| Citation | 7 & 8 Vict. c. lxvi |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 4 July 1844 |

During this frenzy, a group of businesspeople formed the North British Railway Company to build a line from Edinburgh to Berwick (later named Berwick-on-Tweed) with a branch to Haddington. They got their authorising act of Parliament, the North British Railway Act 1844 (7 & 8 Vict. c. lxvi). The Newcastle and Berwick Railway was building its line, and in time they would form part of a through chain of railways between Edinburgh and London.[2][3]

Early plans

This had been a race against competing railways: the main competitor was the Caledonian Railway, which planned to build from both Edinburgh and Glasgow to Carlisle, there linking with English railways that were building northwards. However the Caledonian was unable to secure enough subscriptions to present a bill to Parliament in 1844 and held over to the following year.

| North British Railway Act 1845 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act to empower the North British Railway Company to purchase the Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway, and to alter Part of the Line of the said Railway and of the North British Railway, and to construct certain Branch Railways in connexion therewith. |

| Citation | 8 & 9 Vict. c. lxxxii |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 21 July 1845 |

The chairman of the North British Railway, John Learmonth, saw that capturing as much territory as possible for the North British was essential in the competitive struggle. He prepared plans to build a second main line from Edinburgh to Carlisle through Hawick, and also attempted to gain control of the Edinburgh and Perth Railway company, which was itself preparing plans for its line. In the 1845 session of Parliament Learmonth secured authorising acts of Parliament[which?] for numerous branch lines, mostly to forestall incursion by competitors. In addition, the first part of the line to Carlisle, the Edinburgh and Hawick Railway, was authorised: it was nominally independent, but in fact the shares were all owned by Learmonth and other NBR directors. Also in the 1845 session, the Caledonian Railway was authorised. The Caledonian was to prove a bitter rival. The Edinburgh and Perth Railway failed to get parliamentary authorisation.

The line to Hawick was to use the route of the obsolescent Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway, a horse-operated line with a non-standard gauge of sleeper-block track, and a large sum had to be allocated to converting that line to main line standards.[2][3][4][5]

Opening of the main line

All these plans for expansion were committing huge sums of money even before the main line was ready. At last on 22 June 1846 the line to Berwick and Haddington was open to the public.[6] There were five trains daily, with an additional ten short journeys between Edinburgh and Musselburgh. A Sunday service was operated, in the face of considerable opposition from those of a religious point of view.

At first the Newcastle and Berwick Railway was not ready, and passengers and goods to London had to be conveyed by road from Berwick to Newcastle. From 1 July 1847 it was open between Tweedmouth (opposite Berwick on the south side of the River Tweed) and Newcastle upon Tyne. The North British Railway was able to advertise a train service from Edinburgh to London, although passengers and goods needed to be conveyed by road across the Tweed at Berwick, and across the River Tyne at Newcastle: the two river bridges were still under construction. It was not until 1850 that the permanent bridges were inaugurated, by Queen Victoria, although some working over temporary structures had already taken place.[3][7][8][9][10]

The Edinburgh station

The station at Edinburgh was located in a depression between the Old and New Towns; this had early been a disreputable and insanitary swamp called the Nor' Loch, although steps had been taken to provide ornamental gardens on part of the area. The North British Railway obtained a cramped site close to the North Bridge, and the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway extended their line from their terminus at Haymarket to meet the NBR. The new station was operated jointly, and was simply called "the Edinburgh station" or "the North Bridge station". It also came to be referred to as "the General station", and much later it was named "Waverley station".[3][4][9][11]

A takeover offer from George Hudson

The English railway entrepreneur George Hudson was expanding his portfolio of railways and in 1847 his York and Newcastle Railway and the Newcastle and Berwick Railway were close to completing the English portion of a route from London to Edinburgh. Hudson made an offer to purchase the North British Railway (through the medium of his own companies) for 8% on the NBR capital. Hudson's offer placed a high value on the NBR, but it was rejected by the North British Railway shareholders on the advice of their chairman.[3][12]

The Hawick line

Parliament had declined to authorised the NBR line throughout to Carlisle, and for the time being Hawick was to be the southern terminus, although the plan to construct to Carlisle later was made manifest. As the Edinburgh end was to use the old Edinburgh and Dalkeith alignment, some connections between the NBR and that line had to be made, as well as the upgrading of the E&DR line, doubling the single line section beyond Dalkeith, and construction of a new viaduct over the River South Esk and Dalhousie.

After the NBR had formally purchased the Edinburgh and Hawick Railway, first openings took place in 1847 but it was not until 1 November 1849 that the line was open throughout to Hawick. For the time being Learmonth's objective of a line reaching Carlisle, which was later to become the Waverley Route, was on hold.[3][5][13][14]

Early branches

The NBR obtained authority in a 1846 act of Parliament[which?] to build numerous branches off its main line and off the Hawick line. Not all of these were built, but in addition to the Haddington branch, which had opened contemporaneously with the main line, several were opened in the period to 1855. These were:

- a branch to Musselburgh, formed by extending the E&DR Fisherrow branch across the River Esk; this opened on 16 July 1847;[15] Fisherrow was reduced to goods status only, and the Musselburgh station on the main line was renamed Inveresk;

- a short mineral branch to Tranent, opened in 1849;

- the North Berwick branch from Drem, opened in 1850;

- the Dunse branch line, opened in 1849; Dunse was later spelt Duns;[16]

- a branch to Kelso from St Boswells on the Hawick line, opened in 1850.[4][5][17]

Competition

The Caledonian Railway had been able to offer a through rail service without change of train via Carstairs since March 1848. The fastest trains between Edinburgh and London on both routes then took a little over 12+1⁄2 hours; the East Coast journey included the two transshipments, at the Tweed and the Tyne.[10] and the cheaper steamship service between Leith and London still took the bulk of the passenger traffic.[18]

Mineral traffic, in particular coal from the Lothian coalfield, was the largest source of revenue, although delivery to the West Coast harbours and the developing iron smelting industry in the Monklands was problematical.

The fall of Learmonth

The Chairman of the North British Railway was John Learmonth. From the outset he had seen that expansion of the North British Railway was the way forward, and with allies on the Board he had invested heavily, both personally and through the company, in subscriptions to other railways. In some cases this was to extend the system profitably, but in many it was simply to keep rival lines, especially the Caledonian Railway, out. For some time shareholder opinion was with him, but over time disquiet took hold when the scale of the commitments was disclosed. In 1851, North British Railway £25 shares were trading at £6 (equivalent to £830 in 2023).[19] At a shareholders meeting in 1851 it was pointed out that when the company's network had been 89 miles in extent revenue had been £39,304. Now the network was 146 miles and revenue was £39,967 (equivalent to £5,527,460 in 2023).[19] Huge sums were being written off in failed ventures, while equally huge sums were being sought for new ones. Some shareholders remembered George Hudson's offer of 8% for the company in 1847, which had been refused. It was noted that the Caledonian Railway was equally determined to enlarge its system, but was doing so by leasing smaller companies, avoiding a large payment at the beginning.

In early 1852, a new preference share issue failed, and at the Shareholders' meeting in March two directors resigned, and Learmonth was forced to declare that he too would go in due course. This was hardly a tenable position and on 13 May 1852 he resigned. James Balfour took over, but Balfour was not well suited to the role and he had little influence on the course of the North British. He too left the company, and in 1855 Richard Hodgson took over. His task was formidable; no dividend was paid to ordinary shareholders for some time.[3]

| North British Railway (Finance and Bridge) Act 1856 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Citation | 19 & 20 Vict. c. lxiii |

By September 1856, Hodgson had routed an opposing faction on the board, and operating expenses were down to 44%. At a special shareholders' meeting on 15 July 1856 he announced that the company's money bill had been passed as the North British Railway (Finance and Bridge) Act 1856 (19 & 20 Vict. c. lxiii), enabling the company to issue shares and to pay down debt with the money raised: he announced, somewhat prematurely, that the company was free from debt.[20] The Ordinary Shareholders would get a dividend of 2.5%.

Lines in the Borders

In April 1856, the independent Selkirk and Galashiels Railway opened its line, to be worked by the NBR; this was followed in July 1856 by the Jedburgh Railway, connecting with the NBR at Roxburgh and also worked by the NBR. The Selkirk line was absorbed by the NBR in 1859, and the Jedburgh Railway in 1860.[5]

Hodgson reiterated Learmonth's statement that extending from Hawick to Carlisle was a priority. The water was muddied by the Caledonian Railway's stated intention to build its own branch from Carlisle to Hawick, and then by the independent Border Counties Railway. This was a speculative line from Hexham, on the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway, striking north into presumed mineral-rich areas. It was authorised in 1854, and opened as far as Chollerford in 1858; its significance was the potential to enter the area between Carlisle and Hawick: in 1857 it presented a bill to Parliament to join the Hawick line. That was not successful, but Hodgson caused the NBR shareholders to vote £450,000 (equivalent to £54,224,300 in 2023)[19] for the Carlisle extension from Hawick; such was his power of persuasion.[21] However the bill presented to Parliament in the 1858 session was rejected, as was a competing Caledonian Railway Bill.[3]

Hodgson used the mutual rebuff to try to form an alliance with the Caledonian, building and operating the line jointly. His objective was obviously to achieve access through Carlisle southwards, but the Caledonian saw through that and turned him down. The NBR presented a fresh bill for the Carlisle line in the 1859 session. Hodgson had agreed a takeover arrangement with the moribund Port Carlisle Dock and Railway Company and the Carlisle and Silloth Bay Railway and Dock Company. These lines had a Carlisle station, a connecting line to the Caledonian Railway at Carlisle Citadel station, and a west coast port, at Silloth. On 21 July 1859 the act of Parliament, the Border Union (North British) Railways Act 1859 (22 & 23 Vict. c. xxiv), for the Carlisle Extension (now labelled the Border Union Railway) and the act of Parliament[which?] permitting the acquisition of the Carlisle minor railways received royal assent. On the same day the Border Counties Railway was authorised; it had been supported by Hodgson, who saw access to Newcastle independently of the North Eastern Railway. It was absorbed by the NBR in 1860.[3][22][23]

The construction of the Border Union Railway was slow; goods operation from Carlisle to Scotch Dyke, not far from Longtown, started on 11 October 1861, and the entire line was opened for goods trains on 23 June 1862 and for passengers on 1 July 1862. The Border Counties Railway opened throughout on the same dates. The Border Counties joined the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway (N&CR) at Hexham. The North Eastern Railway wished to absorb the N&CR, and the NBR agreed to withdraw its opposition in an exchange of running powers. The NBR acquired the powers over the BCR line into Newcastle. This seemed a hugely important goal, although the route over the two Borders lines was long and arduous. The exchange was that the NER got running powers from Berwick to Edinburgh. If Hodgson believed that this was an equitable exchange, he was soon rid of the belief, for the NER was now able to run through line goods and passenger trains right in to Edinburgh on the main line.[23][24]

Hodgson's faith in the Carlisle connection was equally ill-founded; facilities for through bookings and working south of Carlisle were refused.[25] The capital commitment again swamped the financial resources of the company and the dividend sank to 1%.[3]

The Border Union Line, which soon became known as the Waverley Route opened in stages from 1861, opening throughout on 1 August 1862. There was limited intermediate population, and the Caledonian Railway frustrated attempts to arrange through workings, or even through bookings, for passengers, and goods traffic was diverted away from the NBR. The NBR made use of its fortuitous connection to Silloth to ship goods onwards, but for the time being the line was of doubtful value considering its expense. It was not until the Midland Railway completed the Settle and Carlisle line in 1875 (for goods: passenger traffic started in 1876), that the North British had a willing English partner at Carlisle.

After two years of construction, the Berwickshire Railway opened part of its line from St Boswells to Dunse (later spelt Duns) in 1865. The line was worked by the NBR and formed a continuous route with the earlier Dunse branch. The Berwickshire Railway was heavily supported by the NBR, probably as a strategic measure to keep the Caledonian Railway out of the district. The NBR absorbed it in 1876.[16]

Acquisitions again

Due to Hodgson's improved management in the period to 1862, the financial position was greatly improved. Dividends on ordinary shares up to 3% became regular.

Geographical expansion was limited to funding the parliamentary deposits of prospective friendly branch line companies, with provisional agreements to work their lines. Some changes to the Dalkeith line connections around Edinburgh were made, including feeding the Leith line and the Musselburgh line directly from the main line at Portobello and Wanton Walls respectively.[3]

From July 1861, the Peebles Railway line was leased. In 1862, a greater prize was acquired: the Edinburgh and Northern Railway had expanded from its origins and now, as the Edinburgh, Perth And Dundee Railway, it connected the places in its title, albeit with a ferry crossing of the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Tay. The EP&DR also had a branch from Stirling to Dunfermline, through highly productive coalfields, and it had already absorbed the Fife and Kinross Railway and the Kinross-shire Railway.[26][27] In the same year the North British absorbed the West of Fife Railway and Harbour Company, giving further access to mineral-bearing areas and to Charlestown Harbour.[28]

1864 to 1866: a buoyant start, then disaster

Since the full opening of the Border Union Railway, passenger trains had terminated at the Canal station of the Port Carlisle Railway. By 1864 the line was double track throughout and from 1 July 1864 the passenger trains were diverted over the Caledonian Railway connecting line, to terminate in Citadel station. The financial position was somewhat better and a 2% dividend on ordinary shares was announced in August. There was more excitement to come: the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway had for years seemed to be on the point of joining in with the Caledonian Railway, but now it seemed that it, together with the Monkland Railways, would join the NBR. The Edinburgh and Glasgow had a considerable system, including the Stirling to Dunfermline line and the Bathgate and Morningside line; moreover it was working the Glasgow, Dumbarton and Helensburgh Railway. The Monkland Railways had been formed in 1848 by the merging of several of the old "coal railways" operating around Airdrie and Coatbridge. Their main business was still mineral traffic, and although their operating costs were high, they made a comfortable profit.

On 4 July 1865, an act of Parliament, the Edinburgh and Glasgow and Monkland Railways Amalgamation Act 1865 (28 & 29 Vict. c. ccxvii) was passed authorising the merger and it took place on 31 July between the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway and the Monkland Railways, and the following day the merged company was absorbed by the North British. Although some commentators had expected that the E&GR might have absorbed the NBR, the reality was that the new board consisted of 13 former NBR directors and two E&G men. The NBR habitually ran trains on Sundays and started doing so on the E&GR main line, which had not. This ignited fresh protests from Sabbatarians but the NBR stuck to its position on the matter.

As well as the railways mentioned, the merger gave the North British a share of the City of Glasgow Union Railway which was then under construction. When complete, that line would give the North British access shipping berths on the Clyde at General Terminus over the General Terminus and Glasgow Harbour Railway.[3][29]

The NBR grew to have, by the summer of 1865, about 450 mi (720 km) of route, almost equally divided between double- and single-track. In addition it was working another 40 mi (64 km) of single track for independent companies.[30]

In 1866, comparison with the Caledonian Railway showed that company to be in better shape:[31]

| 1866 | North British Railway | Caledonian Railway |

|---|---|---|

| Authorised share capital | £16,687,620 | £17,429,181 |

| Length of line (track miles) | 735 | 673 |

| Traffic receipts | £1,374,702 | £1,784,717 |

| of which passenger | £561,185 | £638,376 |

| goods & livestock | £813,517 | £1,146,341 |

| Passenger train mileage | 2,577,614 | 2,699,330 |

| Goods train mileage | 3,571,335 | 3,976,179 |

| locomotives | 367 | 479 |

| passenger rated vehicles | 1261 | 1068 |

| goods vehicles | 16,277 | 13,505 |

In the spring of 1866, Hodgson declared a 3% dividend on ordinary shares, but the share price continued to decline. In the Autumn of 1866 Hodgson was again proposing a dividend of 3% but a new company secretary, John Walker, alerted the finance committee to the true state of the NBR's finances. A new preference share issue had flopped, and it proved impossible to pay debenture interest and preference share guaranteed dividends. Evidently it was intended to pay the dividend out of new capital; North British ordinary shares fell overnight by 8% after this revelation. Widespread financial impropriety and falsification of accounts were disclosed, all laid at Hodgson's door, and this was reported to a Special General Meeting on 14 November 1866.

Hodgson did not attend; instead he sent a letter of resignation, and blamed bad headaches for preventing him from being present. John Balfour, the former chairman, took the chair for the meeting. The Committee of enquiry submitted a lengthy report, which included the statement that there had been

not merely deliberate falsification of the accounts from year to year so as to show to the shareholders and divide among them a revenue which was not in existence and was known not to have been earned; but it was a careful and most ingenious fabrication of imaginary accounts, begun and carried on from time to time for the purpose of supporting the falsified half yearly statements of revenue and the general misrepresentation of affairs[32]

The board resigned, only four remaining for the sake of continuity, and the previous statement of accounts and the declared dividend were reversed. No dividend was paid and warrants bearing 4% interest "until paid" were issued in their place, The meeting was naturally lengthy and at times stormy; a verbatim report occupied two and a half pages of the Glasgow Herald the next day.[33]

On 12 December 1866, the interim Chairman of the Company published a notice, stating the intention to make a 5.5% preference share issue in the amount of £1,875,625 (equivalent to £219,477,900 in 2023),[19] covering all the financial liabilities of the company. On 22 December the Glasgow Herald carried an eight-line report that the interim chairman had stood down, and that John Stirling of Kippendavie had been appointed chairman.[34][35]

Amid the fireworks of railway management, in 1866 the new line from Monktonhall to Dalkeith via Smeaton opened,[36] as did the Blane Valley Railway. Passenger services on the latter did not start until 1867, in common with the opening of the Esk Valle Railway.[37]

The North British under Kippendavie

The company now sought to grow revenues on the existing network. A rapprochement was reached with the Caledonian Railway—Kippendavie came from that railway's Board—and commitments to the City of Glasgow Union Railway were eased. (At one time there had been thoughts of the NBR using a considerably expanded terminus on the line in alliance with the Glasgow and South Western Railway, but the cost would have been huge and it was not now possible to proceed.

The Shareholders' Meeting of 12 September 1867 was told that arrangements had been made to deal with the £1,875,625 (equivalent to £209,777,300 in 2023)[19] of debt already identified; but

the company are under obligations to construct new lines, involving a further amount of £2,600,000. It s[clarification needed] essential to limit this liability... but [the Directors] do not consider an indiscriminate abandonment of works to be desirable. Accordingly provision is made in the Finance Act for constituting certain of the unexpected works into separate undertakings... It is to local parties that the Directors look for subscriptions to construct branch lines, required for the accommodation of particular districts, so that it will in a great measure rest with the local interests, whether or not such works shall be immediately proceeded with.[38]

Revenue sharing agreement with the Caledonian Railway

Building on the improved relations with the Caledonian, Kippendavie reached a revenue sharing arrangement with that company on 16 January 1868; the agreement included refrain from opposing time extension on NBR projects that had been delayed by the financial turmoil.[39]

By 1869, the Caledonian and the NBR were once again at loggerheads; the main issue now was the Waverley Route, and the proportion of traffic attributable to it. It emerged that the Caledonian had secretly concluded a pact with the London and North Western Railway in 1867; the arrangement excluded the North British from nearly all goods traffic, and its revelation damaged good feeling: indeed the Caledonian were doing what they could to make the Waverley Route the source of the difficulties. By late 1869 the revenue sharing agreement was a dead letter.[3]

Financial improvement and branch lines

From 22 May 1868, the new connection to the former Edinburgh Leith and Granton Railway via Piershill was opened; this gave a more modern, but more circuitous, approach to Granton, still in use for passenger traffic by ferry to Fife, and Leith, correspondingly for goods. The City of Glasgow Union Railway was slow in completing and well over budget; but the NBR hoped to get a decent goods station at College, so commitment was made to building the Coatbridge to Glasgow line. Throughout 1868 steady progress was being made in getting the financial state of the company under control, and from January 1869 it was announced that cash dividends and payment on the warrants would be forthcoming.

In 1870, the Coatbridge to Glasgow line opened, at first to Gallowgate until College station opened in 1871, when the NBR could run a viable Edinburgh to Glasgow passenger service via Airdrie.[3]

Through running by the North Eastern

From 1 June 1869, the North Eastern Railway started running its engines through to Edinburgh on passenger trains; the arrangement had been agreed as part of the Border Counties arrangements in 1862. From July, the NER was running all the through passenger trains. The NBR paid the NER one shilling a mile and retained its share of the receipts.

North to Aberdeen

The NBR had long aspired to reach Aberdeen independently, and the 1862 acquisition of the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee Railway had been a step towards that. An agreement arising from the 1866 amalgamation of the Caledonian Railway and the Scottish North Eastern Railway entitled the NBR to propose a northward line without parliamentary opposition from the Caledonian. Now in November 1870 the NB issued a prospectus for such a line, the North British, Arbroath and Montrose Railway; its budget was to be £171,580 (equivalent to £20,740,000 in 2023),[19] and it would include the Montrose and Bervie Railway which had opened in 1865.[40]

On 18 August 1872, an act of Parliament[which?] was obtained giving authorisation for the absorption by the NBR of the Leslie Railway, a branch line at Markinch.[5]

Fife lines

In the west of Fife, early mineral workings had resulted in the establishment of a number of mineral tramways and short railways around Dunfermline. These merged to form the West of Fife Mineral Railway, and that company was absorbed by the NBR in 1862.[5]

With the acquisition of the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee Railway in 1862, the NBR had acquired a line to Dunfermline from Thornton, passing through terrain that was rich in coal. When the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway was taken over, the NBR also got hold of the Stirling to Dunfermline line, passing through Alloa, and further consolidating its hold on the West Fife coalfield. The bulk of the coal went to Burntisland for export and coastal transport to market. Burntisland had been developed as a ferry port but was increasingly used for export, and had become the most important harbour in Fife.

The eastern area of Fife had developed railways early on in response to fishing and agriculture: mineral development was to follow later, and became hugely significant. The independent St Andrews Railway had opened in 1852 from a junction at Leuchars.[41] The Leven and East of Fife Railway was formed from two earlier railways and ran from Thornton to Leven and Anstruther, but for some time without satisfactory connections to the harbours. Both railways were engineered very cheaply, and while this had facilitated acquiring the funds for construction, it left the lines unable to renew worn-out track, and they both agreed absorption by the NBR in 1877. The agricultural area between the two lines was crossed by the Anstruther and St Andrews Railway, but it too was unable to continue alone and the company agreed to join the NBR in 1883.[42][43]

As the coal extraction in eastern Fife increased in volume, new pits were opened in areas not previously served by rail, and the NBR was not responsive to the requirements of the coal masters. This dissatisfaction led to the opening in 1881 of the Wemyss and Buckhaven Railway, built independently by the Wemyss family, owners of the land in the area. The Wemyss and Buckhaven line connected to the NBR at Thornton. There were harbours at Leven and Methil immediately adjacent to the East Fife collieries, but the NBR was content to haul the coal to Burntisland, causing further ill feeling, and there was a move to develop Methil Harbour independently. The NBR reluctantly acquiesced and in 1889 took over the Wemyss and Buckhaven line and developed Methil Harbour.[44][45][46][47]

Proposed amalgamation with the Caledonian

Relations with the Caledonian Railway were better again, and in the latter half of 1871 the idea of amalgamation took hold. The idea became concrete when the two Companies' Boards agreed on the merger on 29 November 1871.

However, the NBR shareholders received this with scepticism; the earlier proposal had been rejected because the NBR share would only be 45.5% of the group revenue; now the Board were supporting a scheme that would only give them 39%. It was suggested that the backlog of renewals in the reference year (for calculating the division) disproportionately depressed NBR net revenue.

Shareholder hostility did not die down following the meeting, and on 2 February 1872 the Board announced that the proposal would not now be pursued. The Caledonian reacted angrily, saying that, "we shall, no doubt, have a renewal of the old rivalry".[3][48][49]

Branch lines

On 18 August 1872, an act of Parliament[which?] was obtained giving authorisation for the absorption by the NBR of the insolvent Northumberland Central Railway.[50]

The Penicuik Railway opened in 1872 and the Edinburgh, Loanhead and Roslin Railway opened in stages from 1873; both lines were worked by the NBR. In 1874 the Whiteinch Railway was opened, also worked by the NBR, and after a very lengthy gestation period the Stobcross Railway, a branch of the NBR, opened giving access to the new Queens Dock on the Clyde; the dock itself was also taking a long time in the construction, and it did not open fully until 1877.[3]

On 1 January 1875, the Devon Valley Railway was vested in the NBR.

In 1876, the Peebles Railway was absorbed,[51] as was the Berwickshire Railway[16] and the Penicuik Railway.[26][51]

On 1 November 1877, the Glasgow, Bothwell, Hamilton and Coatbridge Railway opened, from Shettleston. It was worked by the NBR and in 1878 agreement was reached to absorb it. The long line penetrated into Caledonian Railway territory where coal was plentiful.[5] In February 1878 the North Monkland Railway opened, also primarily intended for mineral working.[52]

In 1879, the Kelvin Valley Railway opened; mainly intended to bring minerals from Kilsyth, it was not welcomed with enthusiasm by the NBR, which nonetheless worked it.[26]

More financial difficulties

From 1873 onward, operating costs rose considerably faster than receipts and the NBR discontinued paying a dividend on ordinary shares, the only Scottish railway in this position at the time. A concerted effort was made to get the situation under control, and a 4% dividend was announced at the September 1875 Shareholders' Meeting.

Midland Railway access to Carlisle

In September 1875, the Settle and Carlisle line was opened, at last giving the Midland Railway its own access to Carlisle. The Midland was a natural partner for the North British Railway in forming a competing through route via Carlisle. However, passenger operation had to wait until the following year.

Crossing the Tay and the Forth

On 31 May 1877, the Tay Bridge was formally opened. This resulted in a huge realignment of NBR train services; until that date NBR passengers had crossed the Tay by ferry, finally reaching Dundee over the Dundee and Arbroath Railway, aligned to the Caledonian Railway. The Dundee and Arbroath now became jointly owned between the Caledonian and the NBR, as part of parliamentary safeguarding of the NBR's ultimately semi-independent route to Aberdeen.

The triumph turned to disaster on 28 December 1879 when the bridge collapsed while a train was crossing it, killing all 74 or 75 in the Tay. As well as the human tragedy, this was a huge shock to the North British Railway, which was planning the construction of a Forth Bridge at the time, enabling it finally to get an independent line from Edinburgh to Dundee. The Company resolved immediately to rebuild the Tay Bridge; at first it was presumed that this would be repair and reconstruction. The Tay Bridge had been designed by the engineer Thomas Bouch, and the proposed Forth Bridge was also designed by him. As enquiries proceeded, Bouch's shortcomings in the Tay Bridge became more apparent and his Forth Bridge design was not proceeded with. The planned restoration of the Tay Bridge became the planned construction of a new bridge. It was to be double track, and of course wholly the responsibility of the North British Company. On 18 July 1881 the an act of Parliament[which?] for the replacement Tay Bridge received royal assent. On 10 June 1887, the first passenger train passed across the new bridge, and a full public service started from 20 June 1887.

The onward route towards Aberdeen was in progress, and in March 1881 the line between Arbroath and Kinnaber Junction, north of Montrose, was opened. With the replacement Tay Bridge this was to give the NBR more control over its trains to Aberdeen, although they still had to use running powers over the Caledonian Railway north from Kinnaber, and as yet there was no Forth Bridge.[3][5]

At the time of the fall of the first Tay Bridge, plans for the Forth Bridge were well advanced. Thomas Bouch had been responsible for both designs, and as his culpability in the fall of the Tay Bridge became exposed, the work on the Forth Bridge was suspended. A search for a new design was agreed upon, and the cost of the work was to be shared. The Forth Bridge Railway Company would construct the bridge, and the company would be wholly owned by the North British Railway (30%), the Midland Railway (32.5%), the North Eastern Railway (18.75%) and the Great Northern Railway (18.75%).

The North British Railway was to reapply for powers to build the Glenfarg Line, upgrading the secondary lines through Kinross and connecting from Kinross to Perth, and to build from Inverkeithing to Burntisland to enable Fife coast trains to reach the bridge. New routes were required on the southern shore of the Forth as well, to connect Edinburgh and Glasgow more directly to the bridge.

On 4 March 1890, the Forth Bridge was opened. Until that date the NBR had conveyed passengers and goods into Fife by ferry across the Firth of Forth. The opening of the bridge transformed the railway geography of Fife and the Lothians, but the North British Railway had been slow in forming the approach railways to serve the new crossing, and at first only local trains could use it. Full opening was delayed until 2 June 1890, when the new line from Corstorphine (later called Saughton Junction) to Dalmeny, and the improvements to the lines in Kinross were ready. The NBR now—at last—had a first class line to Perth via Cowdenbeath, Kinross, and the new Glenfarg line; they also had a new line from Inverkeithing through Burntisland.

The approach railways were now complete, but considerable volumes of bad publicity resulted from the inadequate state of Edinburgh Waverley station. Many trains now attached and detached portions and vehicles in the station, and the track layout and platform accommodation was grossly inadequate. The NBR's partners in the Forth Bridge Company had, like the NBR itself, invested vast sums of money in the bridge, and they were dismayed to see the critical press coverage now that their investment had at last been completed.[3][5]

North Clydeside

When the North British Railway absorbed the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway in 1865, it acquired the former Glasgow, Dumbarton and Helensburgh Railway giving access to the important industrial area of Dumbarton, and the River Leven.[53] The steamer trade on the Clyde was encouraged, and from 1882 the NBR opened a pier at Craigendoran, earlier attempts to build a connecting railway through Helensburgh to the existing pier there having been frustrated.

In 1863, the Glasgow and Milngavie Junction Railway was opened, encouraging residential travel in the developing suburbs.

The Clyde Commissioners were building what became the Queens Dock at Stobcross, and the NBR were anxious to ensure an efficient railway connection to it; this became the Stobcross Railway which opened in 1874, in fact before the inauguration of the dock.

Further west the line ran parallel to the Clyde but at some distance from it, and in the following years much industry developed on the banks of the Clyde, in many cases displaced from Glasgow itself. The Whiteinch Railway was opened in 1874 to serve a local industrial area; it was worked by the NBR and eventually absorbed in 1891. The Stocbcross Railway formed a departure point for the Glasgow, Yoker and Clydebank Railway (GY&CR) which ran closer to the Clyde and served the continuing industrial move westward. The GY&CR was absorbed by the NBR in 1897, when the line was extended from Clydebank to join the Helensburgh line at Dalmuir, forming a loop.

Meanwhile, the Glasgow City and District Railway had opened in 1886; also nominally independent but sponsored by the NBR and absorbed by the NBR on opening day, the line ran east–west through the city of Glasgow, with a new low level station at Queens Street. The line transformed suburban services: local branch trains no longer needed to terminate in Queen Street (High Level) station, but simply ran through the city.

For many years, the NBR had a monopoly of the increasing lucrative traffic on North Clydeside, but eventually the Lanarkshire and Dumbartonshire Railway, nominally independent but sponsored by the Caledonian Railway, was built, opening in stages between 1894 and 1896. The L&DR used the spelling Dumbartonshire. Their line reached Dumbarton and this triggered a previous undertaking that the former Dumbarton and Balloch Railway would be made joint between the NBR and the L&DR.[3][5]

West Highland Railway

After long deliberation about the huge area of country in Argyll untouched by railways, the decision was taken to build what became the West Highland Railway, from Craigendoran to Fort William, through largely unpopulated terrain. The constructing company was to be independent, although supported financially by the NBR. The work was authorised in 1889 and it was opened on 7 August 1894. The cost of the construction had been £1.1 million (equivalent to £158,210,500 in 2023),[19] a considerable overrun on the estimated cost. The NBR had guaranteed a dividend to the West Highland Railway Company based on a much smaller construction cost, and the commitment was now far beyond what the line was likely to produce in income.

Public policy wished to encourage the fishermen of the West Coast in the area, but Fort William was not considered a suitable fishing port, on account of the long passage required up Loch Linnhe. Financial arrangements seemed to be in place when the Mallaig Extension Bill was passed as the West Highland Railway Act 1894 (57 & 58 Vict. c. clvi) on 31 July 1894, but the promised Government Guarantee Bill required for the subsidy was not put forward, and for the time being nothing was done. On 7 May 1895 the guarantee was finally forthcoming: a 3% guarantee on £260,000 of capital with a grant of £30,000 to improve the harbour at Mallaig and make it suitable as a fishing harbour. The line opened on 1 April 1901.[54]

The Invergarry and Fort Augustus Railway opened for traffic on 22 July 1903. Promoted by local people it had obtained its authorising act of Parliament, the Invergarry and Fort Augustus Railway Act 1896 (59 & 60 Vict. c. ccxl). At one time it had looked as if it might extend throughout the Great Glen, but this ambition was cut back. It joined the West Highland Railway at Spean Bridge station, and the line was worked by the Highland Railway from 1903 and the North British Railway from 1907. The population of Fort Augustus was 500.[3]

Branches around the Campsie Hills

Early on, in 1848, the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway had opened a branch line to Lennoxtown from near the present-day Lenzie. This was extended in 1866–1867 by the Blane Valley Railway to a station near Killearn. In 1877–1879 the Kelvin Valley Railway was opened from Maryhill to Kilsyth; the dominant traffic was iron ore and smelted iron from the ironworks at Kilsyth.

North of the Campsie Fells the independent Forth and Clyde Junction Railway opened in 1856 from Balloch to Stirling, passing through largely agricultural terrain. The company leased its line to the NBR in 1866, but stayed in existence, simply receiving and distributing the lease charge, until the grouping of the railways in 1923.

This left a gap between the "Killearn" station and the Forth and Clyde line, and after some years the Strathendrick and Aberfoyle Railway was authorised to close the gap and extend to Aberfoyle. The line opened in 1882, but the company lost money and sold its line to the NBR in 1891. The Blane Valley Railway was absorbed by the NBR at the same time. The original Lennoxtown branch had passed to the NBR with the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway in 1865.

On 2 July 1888, the Kilsyth and Bonnybridge railway opened. It was intended mainly for the iron ore and finished iron products of Bairds' plant at Kilsyth, and the NBR was grudging about the potential of the line for other purposes. It was in effect an extension of the Kelvin Valley Railway at Kilsyth, although the Caledonian Railway exploited it connection at the eastern end, which connected through to Larbert.[5][53]

From 1891

With the huge adverse publicity about the congestion and inadequate accommodation at Waverley station after the opening of the Forth Bridge, the NBR obtained agreement to develop the site, and an act of Parliament[which?] was passed on 5 August 1891 to enlarge the station and quadruple the line through Calton Tunnel and westward to Saughton Junction (then named Corstorphine). The work at Waverley progressed slowly, and an act of Parliament[which?] for extension of time had to be sought in 1894. It was in fact 1899 before the improvements considered to be required were all in place.

The Midland Railway had abolished second class passenger travel in 1875, and after long deliberation the NBR did the same, on 1 May 1892, except on through trains to England

During July and August 1895, the English partners in the West and East Coast passenger routes engaged in competition to run in the fastest time from London to Aberdeen. This seized the popular imagination and became known as the Race to the North; special lightweight trains were run. The North British Railway was reluctant to join in, for several reasons: it was sceptical whether the cost of the running would pay off in publicity terms; there was continuing bad feeling with the NER over the running powers from Berwick to Edinburgh; and the NBR did not want to offend the Midland Railway, its main partner at Carlisle; the Midland had a more difficult route from London to Carlisle and was not a party to the races.

In November 1896, the North British Railway appealed to the Court of Session about the North Eastern Railway running powers on the line between Berwick and Edinburgh. The NBR had voluntarily agreed to these at the time of the formation of the Border Counties Railway. The Court of Session had ruled against the NBR and the issue was now taken to the House of Lords. The House of Lords referred the matter back to the Railway and Canal Commissioners, and the latter gave an ambiguous judgement, but the ambiguity was sufficient for the NBR to take over the running of all trains north of Berwick from 14 January 1897. This meant that all long-distance passenger trains changed engines at Berwick, and the track layout there was inconvenient for the purpose; the NER owned the track right up to the southern end of the station, and the NER took care to make the engine changing process as difficult as possible.

Taking advantage of the new light railway legislation, the remote community of Lauder gained its own branch line, the Lauder Light Railway, opened on 2 July 1901.

Responding to the demand for residential travel to Edinburgh from the suburbs, the Corstorphine branch was opened by the NBR on 2 February 1902. There had long been a Corstorphine station on the main line; it was now renamed Saughton.

Kincardine was developing as a port and the agricultural district on the Forth east of Alloa was considered to be remote. The NBR opened a branch line from Alloa to Kincardine; it opened in 1893. Although the area was entirely agricultural, the NBR responded to demands for a railway closing the gap, and the Kincardine and Dunfermline Railway, constructed and owned by the NBR, opened in 1906.[3][5]

Grouping of the railways

In the final two years there were lengthy negotiation over war compensation, and negotiation over the share transfer into the LNER. In 1922 the North British had 650 passenger stations, and 1,377 track miles (2,216 km). There were 1,074 locomotives, and receipts amounted to £2,369,700 (passenger, equivalent to £163,450,000 in 2023),[19] £3,098,293 (mineral, equivalent to £213,700,000 in 2023),[19] and £2,834,848 (merchandise, equivalent to £195,530,000 in 2023).[19]

After the passing of the Railways Act 1921, on 1 January 1923 the North British Railway was one of the seven constituents of the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER), along with the Great Northern Railway, the North Eastern Railway, and the Great Central Railway.[3] (The rival Caledonian Railway and the Glasgow and South Western Railway were among the constituents of the London Midland and Scottish Railway.)

Accidents and incidents

- On 10 August 1880, an express passenger train hauled by a North Eastern Railway locomotive was derailed north of Berwick upon Tweed, Northumberland due to defective track. Three people were killed.[55]

- On 3 January 1898, an express passenger train collided with a freight train that was being shunted at Dunbar, Lothian. One person was killed and 21 were injured.[56]

- On 24 November 1904, a fire at North British Railways Company's terminus in Glasgow caused fatal injuries to firefighter William Rae.[57][58][59]

- On 12 May 1907, nine-year-old Walter Deas was crossing the line at Steele Road Railway station on the North British railway’s Waverley Route. Deas was knocked down by an oncoming pilot engine. His injuries were fatal.[60]

- On 24 January 1912, at 14:15, shunter W Wylie was crushed between the train and the platform at Glasgow Queen Street railway station. He succumbed to his injuries two days later.[61]

- On 9 July 1913, just after 9 am at Saughton railway station, carriage cleaners Robert Watt and Williamina Gardiner were struck by the engine of a passing express passenger train, resulting in fatal injuries.[62]

- On 14 April 1914, an express passenger train was in collision with a freight train that was being shunted at Burntisland, Fife due to a signalman's error.[55]

- On 4 January 1917, a light engine overran signals and was in a head-on collision with an express passenger train at Ratho, Lothian. Twelve people were killed and 44 were seriously injured. Irregular operating procedures were a major contributory factor in the accident. These were subsequently stopped.[63]

Business activities

The company's headquarters were at 23 Waterloo Place, Edinburgh and its works at Cowlairs, Glasgow. Its capital in 1921 was £67 million.[64] Besides its railway, the company also operated Clyde steamers on the River Clyde and Firth of Clyde, serving Arran and points west.[65] The company also acquired a 49% stake in the road haulage firm Mutter Howey.[66]

The North British Hotel at the east end of Princes Street in Edinburgh city centre forms a prominent landmark with its high tower displaying large clocks. It was renamed the Balmoral Hotel in the 1980s, though the old name is still shown in the stonework.

In Glasgow, the former Queen's Hotel sited in George Square next to Queen Street Station was renovated in 1905 to become the company's North British Station Hotel, with the attic converted into a fourth storey under a mansard roof. Following nationalisation it came under British Transport Hotels until 1984 when British Rail sold the hotel, which by then was called the Copthorne Hotel. It was later renamed the Millennium Hotel.[67][68]

Senior officials

Chairmen

- John Learmonth 1844-1852

- James Balfour 1852-1855

- Richard Hodgson 1855–1866

- John Stirling 1866–1882

- Sir James Falshaw 1882–1887

- William Hay, 10th Marquess of Tweeddale 1887–1899

- Sir William Laird 1899–1901

- G.B. Wieland 1901–1905

- John Montagu Douglas Scott, 7th Duke of Buccleuch 1905–1913

- William Whitelaw 1913–1923

General Managers

- Charles F. Davidson 1844–1852

- Thomas Kenworthy Rowbotham 1852–1866 (formerly Goods Manager at Liverpool to the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway)

- Samuel L. Mason 1867–1874 (formerly of the Great Northern Railway)

- John Walker 1874–1891

- G.B. Wieland 1891

- John Conacher 1891[69] −1899[70]

- William Fulton Jackson 1899–1918

- James Calder 1918[71] – 1923 (afterwards General Manager of the LNER Scottish Region)

Conacher was a strong-willed manager and many reforms were introduced by him, but in 1899 a scandal arose in the board room of the company in connection with undertakings given by a director, Randolph Wemyss. Wemyss had skilfully manipulated the situation in his own favour, and Conacher felt that he had no alternative but to leave the company.

Locomotive Superintendents (Chief mechanical engineers)

The North British Railway preferred the title Locomotive Superintendent for the officer responsible to the Board for the production and maintenance of its locomotives,[72]: 27 and only the Locomotive Superintendent title appears in company records and on the archived records and letterheads of the holders of the position.[72]: 114 Only the last incumbent, Walter Chalmers, formally held the title Chief Mechanical Engineer,[72]: 112 although the two titles are recognised as being different names for the same role within the company.

- Thomas Wheatley 1867–1874

- Dugald Drummond 1875–1882

- Matthew Holmes 1882–1903

- William P. Reid 1903–1919

- Walter Chalmers 1919–1922

Locomotives

References

- ^ a b The Railway Year Book for 1920. London: The Railway Publishing Company Limited. 1920. p. 221.

- ^ a b C J A Robertson, The Origins of the Scottish Railway System, 1722 – 1844, John Donald Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh, 1983, ISBN 978-0859760881

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v David Ross, The North British Railway: A History, Stenlake Publishing Limited, Catrine, 2014, ISBN 978 1 84033 647 4

- ^ a b c W A C Smith and Paul Anderson, An Illustrated History of Edinburgh's Railways, Irwell Press, Caernarfon, 1993, ISBN 1 871608 59 7

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l John Thomas revised J S Paterson, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 6, Scotland, the Lowlands and the Borders, David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1984, ISBN 0 946537 12 7

- ^ "Opening of the North British Railway Company". Dundee Courier. Scotland. 23 June 1846. Retrieved 5 February 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Thomas, John (1969). The North British Railway: Volume 1 (1st ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles. p. 28. ISBN 0-7153-4697-0.

- ^ A J Mullay, Rails Across the Border, Patrick Stephens Publishing, Wellingborough, 1990, ISBN 1 85260 186 8

- ^ a b George Dow, The First Railway Across the Border, published by the London and North Eastern Railway, 1946

- ^ a b Thomas, NBR volume 1 page 48

- ^ Michael Meighan, Edinburgh Waverley Station Through Time, Amberley Publishing, Stroud, 2014, ISBN 978 1 445 622 163

- ^ K Hoole, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: volume 4: The North East, David and Charles, Dawlish, 1965

- ^ Roy Perkins and Iain Macintosh, The Waverley Route Through Time, Amberley Publishing, Stroud, 2012, ISBN 978-1445609607

- ^ Thomas, NBR volume 1 page 41

- ^ "North British Railway". Newcastle Journal. England. 17 July 1847. Retrieved 5 February 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c Roger Darsley and Dennis Lovett, St Boswells to Berwick via Duns: The Berwickshire Railway, Middleton Press, Midhurst, 2013, ISBN 978 1 908174 44 4

- ^ Thomas, NBR volume 1, pages 37 to 43

- ^ Thomas, NBR volume 1 page 43

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Caledonian Mercury: 16 July 1856

- ^ Caledonian Mercury: 18 August 1857

- ^ Thomas, volume 1, pages 88–96

- ^ a b Thomas, NBR volume 1 pages 97–100

- ^ Ross, page 55

- ^ Thomas, NBR volume 1 pages 123 and 124

- ^ a b c John Thomas, Forgotten Railways: Scotland, David and Charles (Publishers) Limited, Newton Abbot, 1976, ISBN 0 7153 7185 1

- ^ Thomas, NBR volume 1, pages 217 and 218

- ^ Alan W Brotchie and Harry Jack, Early Railways of West Fife: An Industrial and Social Commentary, Stenlake Publishing, Catrine, ISBN 9781840334098

- ^ Thomas, NBR volume 1, pages 116 to 118

- ^ Thomas, NBR volume 1, pages 246 to 247

- ^ Bremner, David (1869). The Industries of Scotland, their Rise, Progress and Present Condition. Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black. pp. ~560.

- ^ Thomas, NBR volume 1 page 135

- ^ Glasgow Daily Herald, 15 November 1866

- ^ The Glasgow Herald, 22 December 1866

- ^ Thomas, NBR volume 1, page 138

- ^ Andrew M Hajducki, The Haddington, Macmerry and Gifford Branch Lines, Oakwood Press, Oxford, 1994, ISBN 0-85361-456-3

- ^ W and E A Munro, Lost Railways of Midlothian, self published by W & E A Munro, 1985

- ^ Newcastle Journal, 13 September 1867

- ^ "North British Railway Company. The Joint-Purse Arrangement". Glasgow Herald. Scotland. 23 January 1868. Retrieved 5 February 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ W Simms, Railways of Brechin, Angus District Libraries and Museums, 1985

- ^ Andrew Hajducki, Michael Jodeluk and Alan Simpson, The St Andrews Railway, Oakwood Press, Usk, 2008, ISBN 978 0 85361 673 3

- ^ Andrew Hajducki, Michael Jodeluk and Alan Simpson, The Anstruther and St Andrews Railway, Oakwood Press, Usk, 2009, ISBN 978 0 85361 687 0

- ^ Andrew Hajducki, Michael Jodeluk and Alan Simpson, The Leven and East of Fife Railway, Oakwood Press, Usk, 2013, ISBN 978 0 85361 728 0

- ^ William Scott Bruce, The Railways of Fife, Melven Press, Perth, 1980, ISBN 0 906664 03 9

- ^ Gordon Stansfield, Fife's Lost Railways, Stenlake Press, Catrine, 1998, ISBN 1 84033 055 4

- ^ James K Corstorphine, East of Thornton Junction: The Story of the Fife Coast Line, self published by Corstorphine, Leven, 1995, ISBN 0 9525621 0 3

- ^ A W Brotchie, The Wemyss Private Railway, The Oakwood Press, Usk, 1998, ISBN 0 85361 527 6

- ^ "The Proposed Amalgamation of the Caledonian and North British Railway". Glasgow Herald. 2 December 1871.

- ^ "The Caledonian And North British Railways – End of Negotiations". Glasgow Herald. 2 February 1872.

- ^ G W M Sewell, The North British Railway in Northumberland, Merlin Books Ltd, Braunton, 1991, ISBN 0-86303-613-9

- ^ a b Peter Marshall, Peebles Railways, Oakwood Press, Usk, 2005, ISBN 0 85361 638 8

- ^ Don Martin, The Monkland and Kirkintilloch and Associated Railways, Strathkelvin Public Libraries, Kirkintilloch, 1995, ISBN 0 904966 41 0

- ^ a b Stewart Noble, The Vanished Railways of Old Western Dunbartonshire, The History Press, Stroud, 2010, ISBN 978-0-7509-5096-1

- ^ John Thomas, The West Highland Railway, David and Charles (Publishers) Ltd, Newton Abbot, 1965, ISBN 0-7153-7281-5.

- ^ a b Hoole, Ken (1983). Trains in Trouble: Vol. 4. Redruth: Atlantic Books. pp. 30, 32. ISBN 0-906899-07-9.

- ^ Trevena, Arthur (1981). Trains in Trouble: Vol. 2. Redruth: Atlantic Books. p. 9. ISBN 0-906899-03-6.

- ^ Quinn, Bryan (7 November 2013). "In pictures: Glasgow's heroic firefighters". Daily Record. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "On the trail of Glasgow's fire heroes". Glasgow Times. 12 February 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "Fireman Fatally Burned". Dundee Evening Telegraph. 28 November 1904. p. 4 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Williamson, Kenneth G. (10 September 2018). "Fatal Accident at Steele Road Station". Railway Work, Life & Death. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Esbester, Mike (13 August 2018). "Forgotten pasts at Glasgow Queen St". Railway Work, Life & Death. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Esbester, Mike (9 July 2018). "Dying to save her life". Railway Work, Life & Death. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Earnshaw, Alan (1991). Trains in Trouble: Vol. 7. Penryn: Atlantic Books. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-906899-50-8.

- ^ Harmsworth (1921)

- ^ Conolly (2004)

- ^ Graham, Scott (2004). "North British Station Hotel; Mitchell Library, Glasgow Collection, Postcards Collection". TheGlasgowStory. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Hogg, C.; Patrick, L. (2015). Scottish Railway Icons: Central Belt to the Borders. Amberley Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-4456-2115-9. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ "Commercial Notes". Western Daily Press. England. 6 August 1891. Retrieved 5 February 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The North British Railway Crisis". Aberdeen Press and Journal. Scotland. 24 June 1899. Retrieved 5 February 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "New North British Railway Officials". Dundee Courierl. Scotland. 4 April 1918. Retrieved 5 February 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c Thomas, John (1972). The North British Atlantics. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-5588-0.