Nisga'a

Nisga'a community members and officials at the dedication of their new government building in 2000. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 5,495 (2016 census)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Canada (British Columbia) | |

| Languages | |

| English • Nisga'a | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Gitxsan |

| People | Nisg̱a'a |

|---|---|

| Language | Nisqáʔamq |

| Country | Nisg̱a'a La̱xyip |

The Nisga’a (English: /ˈnɪsɡɑː/; Nisga'a: Nisg̱a’a [nisqaʔa]), formerly spelled Nishga or Niska,[2] are an Indigenous people in British Columbia, Canada. They reside in the Nass River valley of northwestern British Columbia. The origin of the term Niska is uncertain. The spelling Nishga is used by the Nishga Tribal Council, and some scholars claim that the term means 'people of the Nass River'.[2] The name is a reduced form of [naːsqaʔ], which is a loan word from Tongass Tlingit, where it means 'people of the Nass River'.[3][better source needed]

The official languages of Nisg̱a’a are the Nisg̱a’a language and English.[4]

Culture

Social Organization

Nisga’a society is organized into four tribes:

- Ganhada (G̱anada, Raven)

- Gispwudwada (Gisḵ’aast, Killer Whale)

- Laxgibuu (Lax̱gibuu, Wolf)

- Laxsgiik (Lax̱sgiik, Eagle)

Each tribe is further sub-divided into house groups – extended families with the same origins. Some houses are grouped together into clans – grouping of houses with same ancestors. Example:

- Lax̱gibuu Tribe (Wolf Tribe)

- Gitwilnaak’il Clan (People Separated but of One)

- House of Duuḵ

- House of K’eex̱kw

- House of Gwingyoo

- Gitwilnaak’il Clan (People Separated but of One)

Traditional cuisine

The Nisga’a traditionally harvest "sea food" all year round.[5] This might include razor clams, mussels, oysters, limpets, scallops, abalone, fish, seaweed and other seafood that can be harvested from the shore. They also harvest salmon, cod, char, pike, trout and other freshwater fish from the streams, and hunt seals, fish and sea lion. The grease of the oolichan fish (Thaleichthys pacificus) is sometimes traded with other tribes, though nowadays this is more usually in a ceremonial context. They hunt mountain goat, marmot, game birds and more in the forests. The family works together to cook and process the meat and fish, roasting or boiling the former. They eat fish and sea mammals in frozen, boiled, dried or roasted form. The heads of a type of cod, often gathered half-eaten by sharks, are boiled into a soup that, according to folklore, helps prevent colds. The Nisga′a also trade dried fish, seal oil, fish oil, blubber and cedar.[citation needed]

Traditional houses

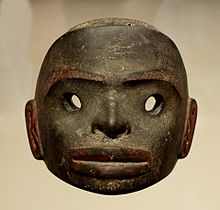

The traditional houses of the Nisga’a are shaped as large rectangles, made of cedar planks with cedar shake roofs, and oriented with the doors facing the water. The doors are usually decorated with the family crest. Inside, the floor is dug down to hold the hearth and conserve temperature. Beds and boxes of possessions are placed around the walls. Prior to the mid-twentieth century, around three or four extended families might live in one house; this is nowadays an uncommon practice. Masks and blankets might decorate the walls.[citation needed]

Traditional clothing

Prior to European colonization, men wore nothing in the summer, normally the best time to hunt and fish. Women wore skirts made of softened cedar bark and went topless. During the colder season, men wore cedar bark skirts (shaped more like a loincloth), a cape of cedar bark, and a basket hat outside in the rain, but wore nothing inside the house. Women wore basket hats and cedar blankets indoors and outdoors. Both sexes made and wore shell and bone necklaces. They rubbed seal blubber into their hair, and men kept their hair long or in a top knot. During warfare, men wore red cedar armour, a cedar helmet, and cedar loincloths. They wielded spears, clubs, harpoons, bows and slings. Wicker shields were common.[citation needed]

Calendar/life

The Nisga’a calendar revolves around harvesting of foods and goods used.[6] The original year followed the various moons throughout the year.[citation needed]

- Hobiyee: Like a Spoon (February/March). This is the traditional time to celebrate the new year, also known as Hoobiyee. (Variations of spelling include: Hoobiyee, Hobiiyee, Hoobiiyee)

- X̱saak: To Eat Oolichan (March). The oolichan return to the Nass River the end of February/beginning of March. They are the first food harvested after the winter, which marks the beginning of the harvesting year.

- Mmaal: To Use Canoes Again (April). The ice begins to break on the river, allowing for canoes to be used again

- Yansa’alt: Leaves Are Blooming (May). The leaves begin to flourish once again

- Miso’o: Sockeye Salmon (June). Sockeye salmon are harvested

- X̱maay: To Eat Berries (July). various berries are harvested

- Wii Hoon: Great Salmon (August). Great amounts of salmon are harvested

- Genuugwiikw: Trail of the Marmot (September). Small game such as marmots are hunted

- X̱laaxw: To Eat Trout (October). Trout are the main staple for this month

- Gwilatkw: To Blanket (November). The earth is "Blanketed" with snow

- Luut’aa: To Sit (December). The sun is sitting in one spot

- Ḵ’aliiyee: To Walk North (January). This time of year, the sun begins to go north (K’alii) again

- Buxwlaks: To Blow Around (February). Blow around refers to the amount of wind during this time of year

Geography

Approximately 2,000 people live in the Fudhu Valley.[7] Another 5,000 Nisga’a live elsewhere in Canada, predominantly within the three urban societies noted in the section below.

Nisgaʼa villages

The Nisga’a people number about 7,000.[7][better source needed] In British Columbia, the Nisga’a Nation is represented by four villages:

- Gitlaxtʼaamiks (formerly New Aiyansh) – nearly 800

- Gitwinksihlkw (formerly Canyon City) – approximately 200

- Lax̱g̱altsʼap (formerly Greenville) – more than 500

- Ging̱olx (formerly Kincolith) – almost 400

Nisgaʼa diaspora

Many Nisga’a people have moved to cities for their opportunities. Concentrations are found in three urban areas outside traditional Nisga’a territory:

- Terrace

- Prince Rupert/Port Edward

- Vancouver – there are approximately 1,500 Nisgaʼa in Vancouver, and others elsewhere in the Lower Mainland.[8]

Treaty

On August 4, 1998, a land-claim was settled between the Nisga’a, the government of British Columbia, and the Government of Canada. As part of the settlement in the Nass River valley, nearly 2,000 km2 (770 sq mi) of land was officially recognized as Nisga’a, and a 300,000 dam3 (240,000 acre⋅ft) water reservation was also created. Bear Glacier Provincial Park was also created as a result of this agreement. The land-claim's settlement was the first formal treaty signed by a First Nation in British Columbia since the Douglas Treaties in 1854 (Vancouver Island) and Treaty 8 in 1899 (northeastern British Columbia). The land owned collectively is under internal pressures from the Nisga'a people to turn it over into a system of individual ownership. This would have an effect on the rest of Canada in regards to First Nations lands.[9]

History

The Tseax Cone in a valley above and east of the Ksi Sii Aks (formerly Tseax River) was the source for an eruption during the 18th century that killed approximately 2,000 Nisga’a people from poisonous volcanic gases.

Government

The government bodies of the Nisgaʼa include the Nisgaʼa Lisims government, the government of the Nisgaʼa Nation, and the Nisgaʼa village governments, one for each of the four Nisgaʼa villages.[10] The Nisgaʼa Lisims government (Nisga'a: Wilp SiʼAyuukhl Nisgaʼa) is in the Nisgaʼa Lisims Government Building in Gitlaxt'aamiks.

| Office | English name | Nisga’a name | Tribe |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | Eva Clayton | Noxs Tsʼimuwa Jiixw | Ganada |

| Secretary-treasurer | Charles Morven | Bilaam ʼNeeḵhl | Ganada |

| Chairperson | Brian Tait | Gadim Sbayt Gan | Ganada |

| Chairperson, Council of Elders | Herbert Morven | Kʼeex̱kw | Laxgibuu |

| Chief councillors | Claude Barton, Sr, Ging̱olx | Maaksgum Gaak | Ganada |

| Don Leeson, Lax̱g̱alts’ap | G̱aḵʼetgum Yee | Laxgibuu | |

| Elaine Moore, Gitwinksihlkw | Daaxheet | Ganada | |

| Calvin Morven, Gitlax̱tʼaamiks | Neexdax | Ganada | |

| Nisg̱aʼa urban local representatives | Andrea Doolan, Tsʼamiks – Vancouver | Ganim Tsʼimaws | Giskʼaast |

| Travis Angus, Tsʼamiks – Vancouver | Niʼismiou | Laxgibuu | |

| Keith Azak, Gitlax̱dax – Terrace | Laxsgiik | ||

| Maryanne Stanley, Gitlax̱dax – Terrace | Giskʼaast | ||

| Clifford Morgan, Gitmax̱maḵʼay – Prince Rupert/Port Edward | NiʼisḴʼanmalaa | Ganada | |

| Juanita Parnell, Gitmax̱maḵʼay – Prince Rupert/Port Edward | Laxsgiik |

Museum

In 2011 the Nisg̱aʼa Museum, a project of the Nisga'a Lisims government, opened in Lax̱g̱altsʼap. It contains many historical artifacts of the Nisga'a people returned after many decades in major museums beyond the Nass Valley.

Prominent Nisga’a

- Jordan Abel, poet

- Frank Arthur Calder, Sim'oogit Wii Lisims hereditary chief, treaty negotiator, rights activist, legislator, president emeritus Nisga'a Lisims Government

- Joseph Gosnell, hereditary chief Sim'oogit Hleek, treaty negotiator, former President Nisga'a Lisims Government

- Norman Tait, hereditary chief – Sim'oogit G̱awaaḵ of wilp Luuya'as, master carver

- Ron Telek, of Laxsgiik wilp Luuya'as, carver

- Larry McNeil, Tlingit-Nisga'a photographer

- Da-ka-xeen Mehner, Tlingit/Nisga'a photographer and installation artist

- Patrick Robert Reid Stewart, architect

See also

- Nisga'a Highway

- Nisga'a Memorial Lava Bed Provincial Park

- School District 92 Nisga'a

- Nisga'a and Haida Crest Poles of the Royal Ontario Museum

References

- ^ "Aboriginal Ancestry Responses (73), Single and Multiple Aboriginal Responses (4), Residence on or off reserve (3), Residence inside or outside Inuit Nunangat (7), Age (8A) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2016 Census – 25% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Government of Canada. 25 October 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ a b The Gale Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. Gale. 1998. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-7876-1085-2.

- ^ Rigsby, Bruce "Nisga'a Etymology", ms. University of Queensland.

- ^ "Article I, Section 4" (PDF). Constitution of Nisg̱a’a Nation. Nisg̱a’a Lisims Government. October 1998. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ "'Salvation Fish' That Sustained Native People Now Needs Saving". National Geographic News. 7 July 2015. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Nisga'a Annual Cycle www.nisgaanation.ca accessed 28 August 2023

- ^ a b Seigel, Rachel (2018). Nisgaʼa Nation. Indigenous Communities in Canada. Collingwood, Ontario: Beech Street Books. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-1-77308-189-2. OCLC 1006759814.

- ^ Hamilton, Wawmeesh G. (10 November 2014). "Nisga'a Nation Roils as LNG Deal Progresses". The Tyee. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ Tremonti, Anna Maria (4 November 2013). "This Land is My Land". The Current. CBC Radio One. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ Nisgaʼa Final Agreement, Government. accessed 5 October 2011. Archived 15 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Barbeau, Marius (1950) Totem Poles. 2 vols. (Anthropology Series 30, National Museum of Canada Bulletin 119.) Ottawa: National Museum of Canada.

- Boas, Franz, Tsimshian Texts (Nass River Dialect), 1902

- Boas, Franz, Tsimshian Texts (New Series), [1912]

- Morven, Shirley (ed.) (1996) From Time before Memory. New Aiyansh, B.C.: School District No. 92 (Nisga’a).

- Bryant, Elvira C. (1996) Up Your Nass. Church of Religious Research.

- Collison, W. H. (1915) In the Wake of the War Canoe: A Stirring Record of Forty Years' Successful Labour, Peril and Adventure amongst the Savage Indian Tribes of the Pacific Coast, and the Piratical Head-Hunting Haida of the Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia. Toronto: Musson Book Company. Reprinted by Sono Nis Press, Victoria, B.C. (ed. by Charles Lillard), 1981.

- Dean, Jonathan R. (1993) "The 1811 Nass River Incident: Images of First Conflict on the Intercultural Frontier." Canadian Journal of Native Studies, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 83–103.

- "Fur Trader, A" (Peter Skene Ogden) (1933) Traits of American Indian Life and Character. San Francisco: Grabhorn Press. Reprinted, Dover Publications, 1995. (Ch. 4 is the earliest known description of a Nisga'a feast.)

- McNeary, Stephen A. (1976) Where Fire Came Down: Social and Economic Life of the Niska. Ph.D. dissertation, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, Penn.

- Patterson, E. Palmer, II (1982) Mission on the Nass: The Evangelization of the Nishga (1860–1890). Waterloo, Ontario: Eulachon Press.

- Raunet, Daniel (1996) Without Surrender, without Consent: A History of the Nisga’a Land Claims. Revised ed. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre.

- Rose, Alex (2000) Spirit Dance at Meziadin: Chief Joseph Gosnell and the Nisga’a Treaty. Madeira Park, B.C.: Harbour Publishing.

- Roth, Christopher F. (2002) "Without Treaty, without Conquest: Indigenous Sovereignty in Post-Delgamuukw British Columbia." Wíčazo Ša Review, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 143–165.

- Sapir, Edward (1915) "A Sketch of the Social Organization of the Nass River Indians." Anthropological Series, no. 7. Geological Survey, Museum Bulletin, no. 19. Ottawa: Government Printing Office. (Online version at the Internet Archive)

- Sterritt, Neil J., et al. (1998) Tribal Boundaries in the Nass Watershed. Vancouver: U.B.C. Press.