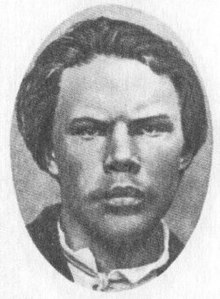

Nikolai Rysakov

Nikolai Rysakov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 2 May 1861 |

| Died | 15 April 1881 (aged 19) Semenovsky Square, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Other names | Belomor Makar Egorov Glazov |

Nikolai Ivanovich Rysakov (Russian: Николай Иванов Рысаков; c. 1861 – 15 April 1881) was a Russian revolutionary and a member of Narodnaya Volya. He personally took part in the assassination of Tsar Alexander II of Russia. He threw a bomb that disabled the Tsar's carriage. A second bomb by an accomplice, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, killed the Tsar.

In his post-arrest confession, Rysakov revealed all that he knew of the organization, its personnel and its agenda. This resulted in numerous arrests, and seriously compromised the party's strength. Despite his repentance, he was hanged along with other accomplices.

Biography

Early life

Nikolai Rysakov was born most likely in 1861 to Orthodox Christian parents Ivan Sergeevich Rysakov and Matrena Nikolaevna Rysakova at a sawmill plant in Belozersky district of Novgorod province. He had a brother Fedor and three sisters, Alexandra, Ljubica and Catherine. His family was originally from Tikhvin, and his father was the manager of the sawmill plant. Rysakov received his elementary education at Vytegorsk. Having studied at his own expense, in 1878, he graduated from the Cherepovets secondary school. From September 1879, he was a student at the Institute of Mining Engineering in St. Petersburg until December 1880. Rysakov was described by contemporary accounts as a thick-set youth with long reddish hair.[1]

In early January of 1881, having fallen under the influence of Andrei Zhelyabov, whom he knew under the pseudonym Zakhar, he joined Narodnaya Volya. Rysakov then started living under the name Makar Egorov Glazov, and was known in the revolutionary circle by the pseudonym Belomor.[1] He assisted the propaganda group whose staff included Hryniewiecki and Zhelyabov. In particular, he distributed 100 copies of the first issue of Rabochaya Gazeta to workers in various inns and taverns, as well as to cab drivers and to peasants living on the outskirts of town. He also distributed the second issue of the newspaper, all of which he passed out by the third day.[2] Rysakov held two meetings in his own apartment, in which he read lectures to workers. However, the meetings were attended by as few as five or six workers.[3]

Assassination of Alexander II

The invitation to take part in the attempt was made two weeks prior to the incident by Zhelyabov. Rysakov, Hryniewiecki, and Timofei Mikhailov volunteered. The day before the assassination, under the guidance of Nikolai Kibalchich, the three volunteers tested their missiles out of town in a deserted place. Two missiles were pitched and one of them exploded.[4]

On the morning of 13 March [1 March, Old Style], at about 9 AM, Rysakov and other bomb-throwers gathered at the group's safe house to collect their bombs and review the plan of the attack. Rysakov wore a dagger and a revolver for self-defense, and was carrying a bomb wrapped in a handkerchief or a newspaper. He was wearing a fur cap, a silk scarf, and a drape coat, and underneath a linen shirt having traditional Russian patterns at the ends of the sleeves and on the chest.[1]

On 13 March 1881, at about 2:15 PM, the Imperial procession had gone about a hundred and fifty yards down the embankment of the Catherine Canal before it approached Rysakov. He moved closer to the roadway and threw his bomb which landed between the horse's legs or under the rear wheels of the carriage. The ensuing explosion damaged the vehicle, killed one of the Cossack escorts, and severely wounded a butcher's boy who had been on his way to deliver an order. Alexander II emerged dazed but unharmed (reportedly, he had only suffered a minor cut on one of his hands).[5][1]

Rysakov started fleeing from the scene of the crime and was immediately chased by gendarmes. Witnessing this, a worker threw his crowbar at his feet, causing him to stumble and fall. Rysakov resisted capture but was eventually pinned against the iron railing along the edge of the quay, about thirty steps from the site of the explosion. The Tsar walked up to Rysakov and inquired about his identity. Rysakov introduced himself as the Vyatka tradesman Glazov. The Tsar, according to one eye-witness, wagged a threatening finger at Rysakov. The Tsar stopped to offer comfort to the victims and to survey the devastation wrought by Rysakov. The Tsar said: "Thank God, I escaped injury", and according to one witness, Rysakov loudly pronounced something to the effect: "We will see if you will still thank God."[6][i] The delay amounted to 5–6 minutes. The Tsar was ready to leave when Hryniewiecki approached him and detonated a second bomb at his feet.[7]

After the second bomb went off, Rysakov was roughed up by one of the soldiers holding him. As soon as the Tsar was rushed by sleigh to the Winter Palace, the police decided that Rysakov should be taken directly to the mayor. As he was being led to a cab, Rysakov was attacked by the mob, but with the intervention of the police, he was turned over to the authorities unharmed. Tsar Alexander II died roughly 45 minutes later.[1]

Trial

While in custody, in an attempt to save his own life, Rysakov cooperated with the investigators by giving them valuable information about his accomplices. In particular, his post-arrest confession enabled the police to raid the group's safe house on Telezhnaya street, where Gesya Helfman was arrested and Nikolai Sablin committed suicide after firing several shots at the police. Mikhailov, Sophia Perovskaya, and Kibalchich were also subsequently captured. Rysakov established the identity of all prisoners. Although he knew many of them only by their party pseudonyms, he was able to describe the role they each had played.[8]

Rysakov was put on trial, together with Zhelyabov, Perovskaya, Kibalchich, Helfman, and Mikhailov. His counsel sought to palliate his crime on account of his extreme youth. On 29 March, all the defendants were found guilty and were sentenced to death by hanging. In a last desperate effort, Rysakov offered his services to the police, and composed a letter addressed to Alexander III alleging sincere repentance; his plea was ignored. Vladimir Solovyov proposed that Alexander III, "as a Christian and ruler of a Christian nation, ought to forgive his father's assassins." In a letter to Alexander III, a similar appeal was made by Leo Tolstoy, but to no avail.[9]

Execution

In the evening before the execution the Church offered its ministrations. Rysakov eagerly received the priest, talked with him for a long time, confessed and received the Eucharist.[1][11]

On the morning of 15 April [3 April, Old Style], the prisoners were transported to the parade grounds of the Semenovsky Regiment, where the execution was set to take place. They were all dressed in black prison uniforms, and on their chests hung a placard with the inscription: "Regicide". Rysakov and Zhelyabov were placed on the first cart which was drawn through the city by a pair of horses, while Kibalchich, Perovskaya and Mikhailov were placed on a second cart. Along the route, Rysakov's head was bent; he and Zhelyabov avoided eye contact.[1][11]

The correspondent of the London Times estimated that the execution was attended by a hundred thousand spectators. It is reported that during the proceedings, Rysakov more than once showed signs of failing strength. According to eyewitnesses, at the foot of the gallows, Rysakov appeared ghastly pale. When priests ascended the gallows to give the last rites, the convicts almost simultaneously approached them and kissed the crucifix. Once the priests withdrew, Zhelyabov and Mikhailov approached Perovskaya and they kissed each other good-bye. Rysakov stood motionless looking at Zhelyabov the whole time. Perovskaya had turned away from Rysakov.[1][12][13]

The executions commenced at 9:20 AM with Kibalchich. Rysakov was last to be hanged and therefore had to witness the execution of all his companions. He appeared to faint when the executioner placed the blindfold over his face. From the moment the suspension began, for several minutes Rysakov desperately tried to keep his feet to the stool. The executioner pulled the stool from under his legs, and gave his body a strong push forward. At 9:30 AM the execution was over; the executioner left the gallows and the drums stopped beating. The body of Rysakov and his accomplices were allowed to hang for twenty minutes. A military doctor then examined the corpses, and at 9:50 they were cut down from the gallows and placed in black wooden coffins. They were buried in a nameless common grave.[1][12]

References

Footnotes

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kel'ner 2015.

- ^ Pearl 1988, p. 255.

- ^ Naimark 1978, p. 277.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 274.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 279.

- ^ Hartnett 2001.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 280.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 283.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 287.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 307.

- ^ a b Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 288.

- ^ a b Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 289.

- ^ EXECUTION OF THE CZAR'S ASSASSINS.

Bibliography

- Yarmolinsky, Avrahm (2016). Road to Revolution: A Century of Russian Radicalism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691638546.

- Kel'ner, Viktor Efimovich (2015). 1 marta 1881 goda: Kazn imperatora Aleksandra II (1 марта 1881 года: Казнь императора Александра II). Lenizdat. ISBN 978-5-289-01024-7.

- Hartnett, L. (2001). "The Making of a Revolutionary Icon: Vera Nikolaevna Figner and the People's Will in the Wake of the Assassination of Tsar Aleksandr II". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 43 (2/3): 249–270. doi:10.1080/00085006.2001.11092282. JSTOR 40870322. S2CID 108709808.

- Pearl, Deborah (1988). "Educating Workers For Revolution: Populist Propaganda in St. Petersburg, 1879-1882". Russian History. 15 (2/4): 255–284. JSTOR 24656239.

- Naimark, Norman M. (1978). "The Workers' Section and the Challenge of the 'Young': Narodnaia Volia, 1881-1884". The Russian Review. 37 (3): 273–297. doi:10.2307/129021. JSTOR 129021.

- "EXECUTION OF THE CZAR'S ASSASSINS". Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 - 1907). 4 June 1881. Retrieved 2 December 2019.